ACCORDING to a recent report from the United Nations, gender equity is a distant goal that may take centuries to achieve. The fields of science and medicine are no exception.

Bias, harassment, hostile work environments, inflexible career pathways, and funding imbalances continue to impede progress. Initiatives such as the UK’s Athena SWAN program and the Australian National Health and Medical Research Council’s new Gender Equity Strategy are working to overcome these obstacles, but large gender gaps persist.

One such gap can be seen in research publishing, where the collective output of male authors exceeds the output of female authors in most disciplines. Possible reasons for this imbalance include lasting under-representation of female researchers, especially at senior levels where research output would typically be higher, as well as retention problems and career disruptions disproportionately affecting female researchers due to the motherhood penalty. Publications are the main currency of research success and reward, so it is crucial to evaluate the gap if we hope to close it.

In a recent study, we examined the gender of the authors on more than 40 million articles published between 2006 and 2020, by calculating the number of articles that list a female or male author in any authorship position. This article set covered research carried out all around the globe and in all fields of study indexed in the Web of Science database. Our study explored how gender gaps varied by country and research field, and whether they were diminishing.

Our study showed that in absolute terms – that is, in the difference in the total number of articles published – the gender gap is not closing in any country. The gap is staying relatively stable in some countries (eg, Canada, Australia, England, US), but in most countries it is expanding.

A somewhat more hopeful picture emerges when we looked at the gender gap in relative terms. As the quantity of total publications has risen steeply in recent decades, a steady gap in absolute terms corresponds to a shrinking one in terms of the proportion of all articles. When we looked in this way, the gender gap was diminishing in most countries, albeit at different rates and from different baselines. For example, women researchers in Australia published about 40% as many articles as men in 2006, but about 70% as many in 2020.

These figures represent all fields of research, but how is Australian medical research faring?

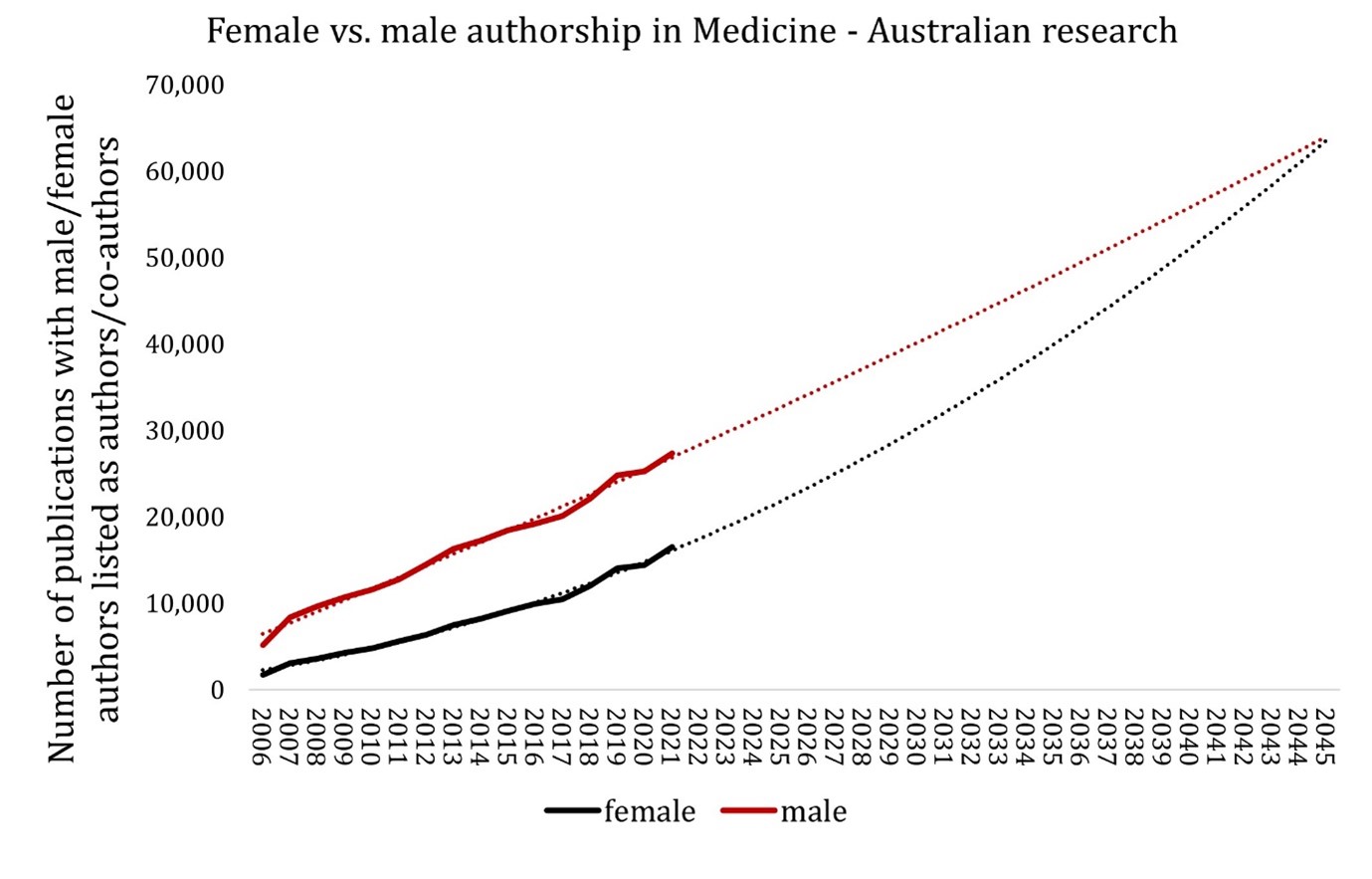

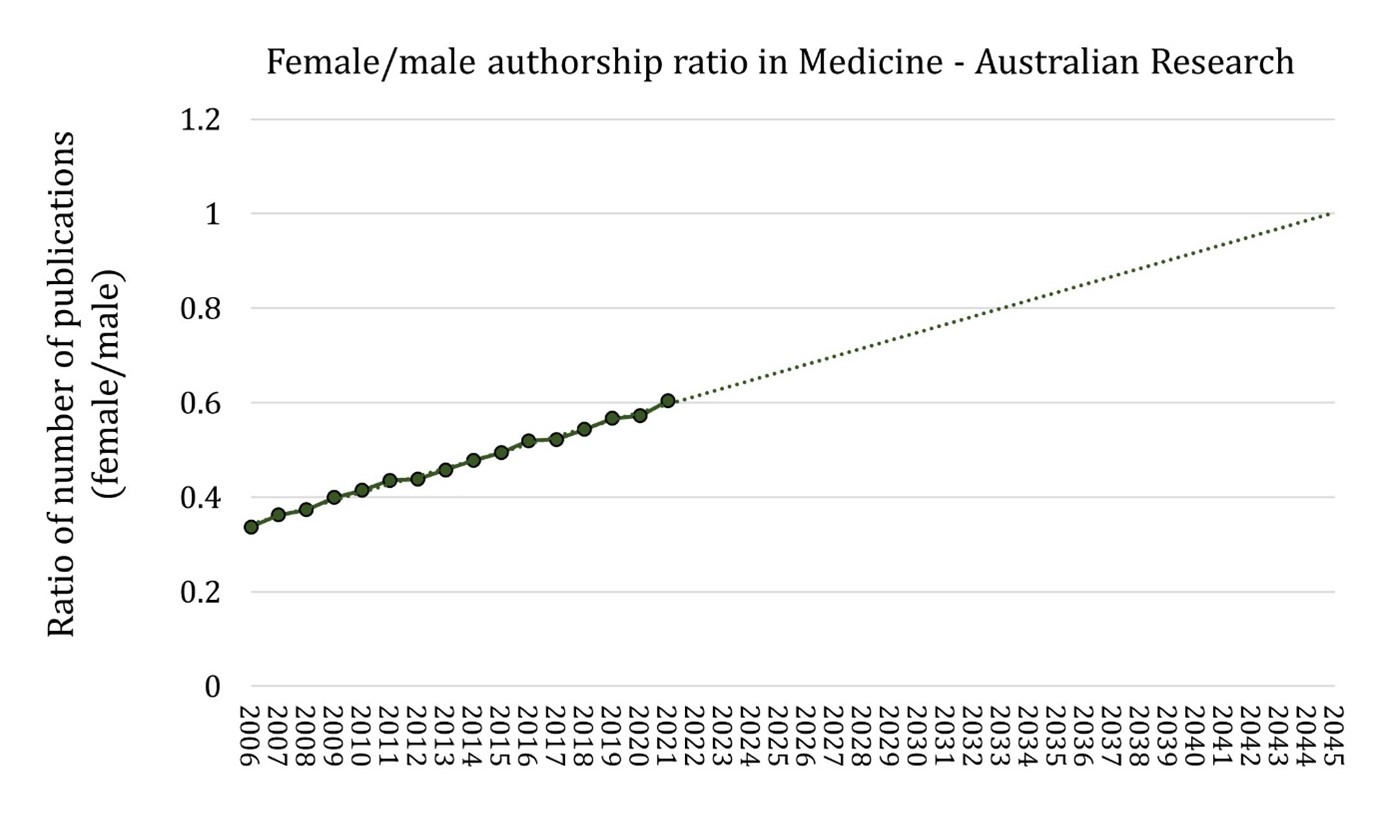

At InSight+’s invitation, we took a closer look at research publications from 2006 to 2021 by Australian authors in journals classified by Web of Science as falling in one of the 60 categories classified under the umbrella of “clinical medicine”. Our graphs display the (absolute) number of articles that have male and female authors for every year (Figure 1) and their (relative) proportion of articles (Figure 2).

Figure 1. Number of publications with female and male authorship in the field of Medicine in Australia

Figure 2. Ratio of the number of publications (female/male) in the field of Medicine in Australia

Figure 1 shows that the number of published medical articles is rising steeply for both women and men.

Although the gap has increased in absolute terms, Figure 2 shows that in relative terms it is gradually shrinking. Women were responsible for 34% as many medical research articles as men in 2006, but 60% as many in 2021. Extrapolating these trends forward, we project that parity will be achieved in 2045. From the standpoint of gender equity that date is far away, and indeed it is slightly more distant than our projection for Australian research as a whole. Nevertheless, it is substantially closer than the disturbingly remote projections for research in many parts of the world.

In addition to examining gender gaps in research production, our study applied a gender lens to the potential disruptive effects of the COVID-19 pandemic. We found that changes in research productivity during 2020, the first year of the pandemic, were generally parallel for male and female authors. Overall, the number of publications in 2020 was only slightly below what previous trends would predict, suggesting that the pandemic did have a major impact on the productivity of researchers. However, in some countries (eg, the Netherlands, the US and Germany), male productivity has been more negatively affected by the pandemic. Overall, female research productivity seems to have been slightly more resilient to the disruptive effect of the COVID-19 pandemic, contrary to many media reports of disproportionate impacts on women. However, it is too early to say whether longer term effects on productivity may emerge. It is clear that the pandemic has negatively affected the momentum of female and male researchers to comparable degrees.

Our study offers some interesting insights into gender gaps in research publishing, including long term trends and shorter term disruptions due to COVID-19. From a glass-half-empty perspective, gender parity in global research publishing is a very long way off. Australian research is no exception, and neither is the large and highly successful fraction of it devoted to health and illness. Male medical researchers in this country are substantially more strongly represented in the scientific journals, collectively publishing five articles for every three published by women. That imbalance seems unlikely to resolve until today’s undergraduates are in their mid-40s.

From a glass-half-full perspective, though, there are some grounds for cautious optimism.

In many parts of the world there is a steady, linear trend towards gender equity in research production and publication. Australia is ahead of the global curve when it comes to the rate of change, and Australian medical research is showing clear movement toward parity.

However, that change is not inevitable. It is the result of systemic and cultural shifts, and its continuation will require ongoing efforts to remove obstacles to equity. These must include initiatives that overcome biases in hiring and retention of female researchers, that support flexible careers and career re-acceleration after disruptions, and that ensure the allocation of research funding promotes these goals. Our research helps to diagnose the magnitude of the current gender imbalance and to make a prognosis for its future, but it is up to medical leaders, educators and funders to design and implement the treatment.

Clara Zwack is a SOLVE-CHD Research Fellow at the University of Sydney. Her research interests are in secondary prevention of coronary heart disease and the cardiovascular health of people with intellectual disability.

Nick Haslam is Professor of Psychology at the University of Melbourne. His research interests are in social psychology and mental health

Milad Haghani is a Senior Lecturer and an ARC DECRA Fellow at the University of New South Wales, Sydney. He is an expert in behavioural modelling as well as in science and research policy.

The statements or opinions expressed in this article reflect the views of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official policy of the AMA, the MJA or InSight+ unless so stated.

Subscribe to the free InSight+ weekly newsletter here. It is available to all readers, not just registered medical practitioners.

If you would like to submit an article for consideration, send a Word version to mjainsight-editor@ampco.com.au.

more_vert

more_vert

“Figure 1 shows that the number of published medical articles is rising steeply for both women and men.”

— but how much is useful ??? Some pieces in MJA are unreadable ( same as RACGP’s AJGP) too.

Is it fair game these days just to whip off a gender pay gap article, knowing it’s going to add to a CV with a woke glow? At the very least, I’d expect some reference to baseline relative numbers of researchers by gender – if women represent 25% of researchers and deliver 25% papers, surely that’s parity? And given the rush to publish these days, surely some reference to quality rather than quantity would strengthen a case for parity – if women contribute less papers overall, but those papers outnumber men in influence (e.g. how often quoted in other papers, numbers of awards, etc), then there would be a case for being over parity regardless of numbers? Then get down to the more general arguments: as stated, women face a ‘pregnancy’ handicap – doh! – so are their papers delivered in less time, and perhaps more efficiently? And finally, what about the cliched issues: women may not WANT to be equal to men in output, being often less stressed to create more balance in their lives juggling wished-for caring responsibilities as well as professional output. In other words, are you naively seeking equality of output, when equality of opportunity is the better achievable goal?

I recently saw a guest on QandA damning Shakespeare as sexist for devoting only 14% of his plays to women, as if this somehow made him less worthy. But what women! How notable and often quoted over the centuries! This article demonstrates naivety and shallow analysis of a similar nature. The Americans gave us Dr Jane Doudna, and Tasmania gave us Elizabeth Blackburn. If the system throws up researchers of dedication and drive like these two, it can’t be too wrong! I suspect success comes to all who give the endeavour the required time and focus.