NEW pre-print research suggests the ongoing outbreak of acute hepatitis in children may have a more complicated cause than first thought.

According to the World Health Organization, as of 8 July 2022, 35 countries have reported 1010 probable cases of severe acute hepatitis of unknown cause in children, including 22 deaths and 46 liver transplants. Almost half of the cases have occurred in the European region, followed by the Americas, the Western Pacific, South-East Asia, and the Eastern Mediterranean.

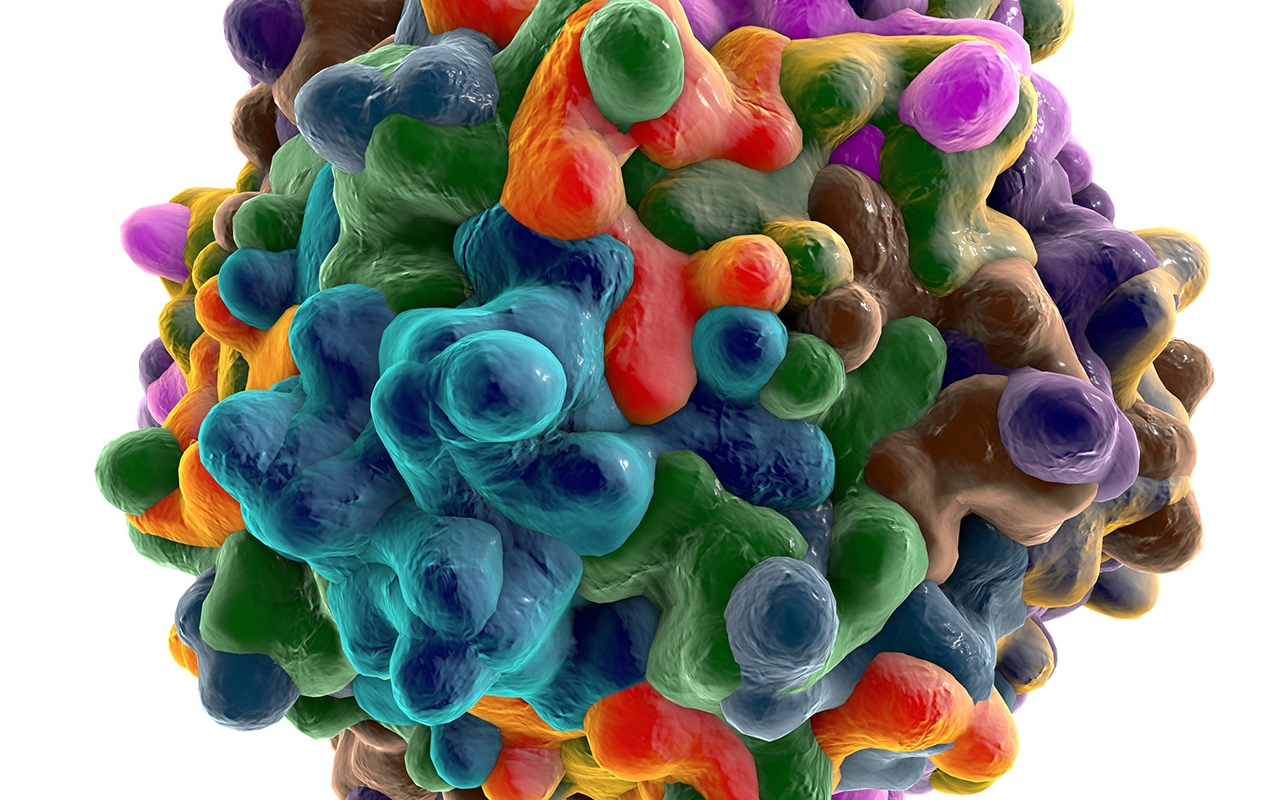

Until recently, the cases have been thought to be associated with previous adenovirus infection in the affected children. Two recent case series published by the New England Journal of Medicine (here and here) concluded that human adenovirus viraemia was present in the majority of children with acute hepatitis of unknown cause, but that whether that association was causative was “unclear”.

But now two pre-print studies published by MedRxiv – here, led by Professor Emma Thompson from the Glasgow Centre for Viral Research and the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine, and here, led by Professor Judith Breuer from University College London and Great Ormond Street Hospital – suggest an alternative explanation.

“These studies suggest that while adenovirus may be a player, the commonality is infection with a dependent, defective virus called adeno-associated virus,” said Associate Professor Simone Strasser, a hepatologist with the Australian National Liver Transplant Unit at Royal Prince Alfred Hospital, and Immediate Past President of the Gastroenterological Society of Australia.

“It’s dependent in the sense that it cannot replicate on its own and needs another virus, and particularly the outer coat of another virus, in order to replicate.”

Thomson and colleagues reported that the adeno-associated virus 2 (AAV2), was “detected in the plasma of 9/9 and liver of 4/4 patients but in 0/13 sera/plasma of age-matched healthy controls, 0/12 children with adenovirus (HAdV) infection and normal liver function and 0/33 children admitted to hospital with hepatitis of other aetiology”.

“AAV2 typically requires a coinfecting ‘helper’ virus to replicate, usually [human adenovirus (HAdV)] or a herpesvirus. HAdV (species C and F) and human herpesvirus 6B (HHV6B) were detected in 6/9 and 3/9 affected cases, including 3/4 and 2/4 liver biopsies, respectively.”

Similarly, Breuer and colleagues found that in the five cases who underwent liver transplantation in their study, high levels of AAV2 were detected in the explanted livers.

“AAV2 was also detected at high levels in blood from 10/11 non-transplanted cases,” they reported. “Low levels of [HAdV] and [HHV-6B], both of which enable AAV2 lytic replication, were also found in the five explanted livers and blood from 15/17 and 6/9 respectively, of the 23 non-transplant cases tested.”

Adding to the picture is the finding in the Scottish study (Thomson et al) of a possible genetic predisposition.

“The class II HLA-DRB1*04:01 allele was identified in 8/9 cases (89%), compared with a background frequency of 15.6% in Scottish blood donors, suggestive of increased susceptibility in affected cases,” they reported.

“AAV has not been recognised to cause human disease, but it is one of the viral vectors that are used for gene therapy, because it can be engineered to deliver DNA to target cells,” said A/Professor Strasser. “It has been recognised to induce an immune response and abnormal liver enzymes in gene therapy trials.”

No link has been found between SARS-CoV-2 infection and the acute hepatitis cases, nor has any association been found with COVID-19 vaccination. In all reported cases, viral hepatitis A, B, C, D and E have been excluded as causes.

A/Professor Strasser told InSight+ that, to her knowledge, no cases had been reported in Australia to date.

“There’s no particular reason why it wouldn’t have shown up here yet,” she said. “Certainly, everyone is on the lookout for it. We see acute liver failure and severe hepatitis in children and adults, not uncommonly.

“But there’s been no unusual cluster of cases or certainly no reports of this occurring in Australia to date.”

According to HealthDirect, symptoms may include abdominal pain, diarrhoea, vomiting, loss of appetite, and jaundice, with most children not experiencing fever.

A/Professor Strasser told InSight+ that GPs suspecting severe acute hepatitis should immediately refer the child to the nearest children’s hospital.

“This is not community management,” she said. “These children should be under the care of a hepatologist and a liver failure unit.”

Even if an outbreak came to Australia, A/Professor Strasser was confident there would be no additional strain on transplant programs.

“Children don’t very commonly progress to liver failure,” she said. “In the global reports, transplant was required in about 5% of cases.

“In Australia, if a child needs a liver transplant, they get a liver transplant.”

Subscribe to the free InSight+ weekly newsletter here. It is available to all readers, not just registered medical practitioners.

more_vert

more_vert