We urge you to play your part in achieving equitable elimination of cervical cancer in Australia by identifying underscreened patients in your practice and letting them know about the option of self-collection

SINCE 1 July 2022, anyone eligible for a cervical screening test (CST) in the National Cervical Screening Program (NCSP) has the choice of human papillomavirus (HPV) testing on either a clinician-collected sample from the cervix or a self-collected vaginal sample without the need for a speculum.

There have been extraordinary advances in our understanding of the pathophysiology of cervical cancer, resulting in HPV-based technologies and tools to prevent and treat it. In 2020, the Director General of the World Health Organization, Dr Tedros Ghebreyesus, announced the 90%, 70% and 90% global targets for HPV vaccination, screening, and treatment of pre-cancers and invasive disease, respectively, paving the way for the previously unthinkable: global elimination of a cancer that affects more than 600 000 women every year.

Australia is on track to be the first country in the world to eliminate cervical cancer, defined as fewer than four cases per 100 000 women, as early as between 2028 and 2035. This enviable achievement is the result of our successful organised screening program, initiated in 1991, the National HPV Vaccination Program introduced in 2007, and since late 2017, a more effective and efficient screening program using 5-yearly HPV testing.

While vaccination will reap long term sustainable rewards, with the oldest vaccinated people now in their early 40s, maximising screening participation is essential for moving the dial in the shorter term. At the end of 2020, more than 30% of those eligible for cervical screening were overdue, although screening participation is expected to increase once data from all 5 years of the first round of the HPV-based program are available.

Many groups have lower screening rates though and, where this can be measured, are over-represented in cervical cancer incidence and mortality. Despite challenges with identification in national datasets which need to be overcome, available evidence highlights that Aboriginal and/or Torres Strait Islander women have more than double the incidence and almost four times the mortality associated with cervical cancer compared with other Australian women. While there is an absence of systematically collected data, there is research evidence confirming that those from some culturally and linguistically diverse (CALD) backgrounds also have higher cancer rates and that people with disability, and those from the LGBTQI+ community have lower than average screening rates. Even more hidden are those who have experienced sexual trauma, have chronic pelvic pain or vaginismus or have had negative screening experiences in the past for whom a speculum examination for a CST is a challenge too far.

Paving the way to universal self-collection in Australia

“Providing everyone the choice to use self-collection has the potential to transform participation in the NCSP, and to reach those who are under– and never-screened.”

In early 2021, following review of the scientific evidence and public consultation around the introduction of self-collection as a universal choice within the NCSP, the Medical Services Advisory Committee (MSAC) recommended that Australia remove restrictions to access to self-collection. On 8 November 2021, the then Minister for Health and Aged Care, Greg Hunt, announced that the Australian Government had accepted this recommendation, stressing that this major policy change was grounded in improving access to screening and ensuring equity.

While self-collection has been available since 2018 within the NCSP, it was previously restricted to those who were at least 30 years of age and two or more years overdue for screening. Uptake of self-collection before July 2022 accounted for less than 1% of those eligible, which stemmed from a combination of health care provider difficulties in assessing eligibility, lack of confidence in its accuracy, confusion about how to facilitate self-collection, limited numbers of laboratories processing self-collected samples, and very low community awareness.

Concerns about accuracy were not surprising as this was consistent with original messages, but since then evidence has continued to strengthen that polymerase chain reaction (PCR)-based tests work equally well on self-collected vaginal samples and clinician-collected cervical samples (unlike older less sensitive signal amplification tests). Furthermore, the lack of Therapeutic Good Administration (TGA)-approved self-collection indications for HPV assays until recently (here, here and here) meant that processing could only occur in the three pathology laboratories across the country which had undertaken in-house validation studies.

However, there are now a range of HPV assays with TGA-approved claims for self-collection with several laboratories offering processing of self-collected samples and more expected to follow.

Clinicians are encouraged to contact their local pathology service to confirm that they can process self-collected vaginal samples, or that they have an arrangement in place to send them on to another laboratory for processing, and to ensure they have the correct swabs, handling requirements and resources to support their patients making an informed decision for self-collection.

Evidence consistently indicates that self-collection is highly acceptable as an alternative to a clinician-collected CST, especially among those who are underscreened, who described it as empowering, supporting bodily control and autonomy, easy to do, convenient, and less embarrassing than a speculum examination. Some would prefer to continue with clinician collection though, especially up-to-date screeners. Others, especially those who hadn’t used self-collection themselves, worried about taking the sample incorrectly, but can be reassured that HPV tests on self-collected samples in Australia have a cellularity control so an empty or inadequate sample won’t lead to a negative HPV test result.

Self-collection in practice

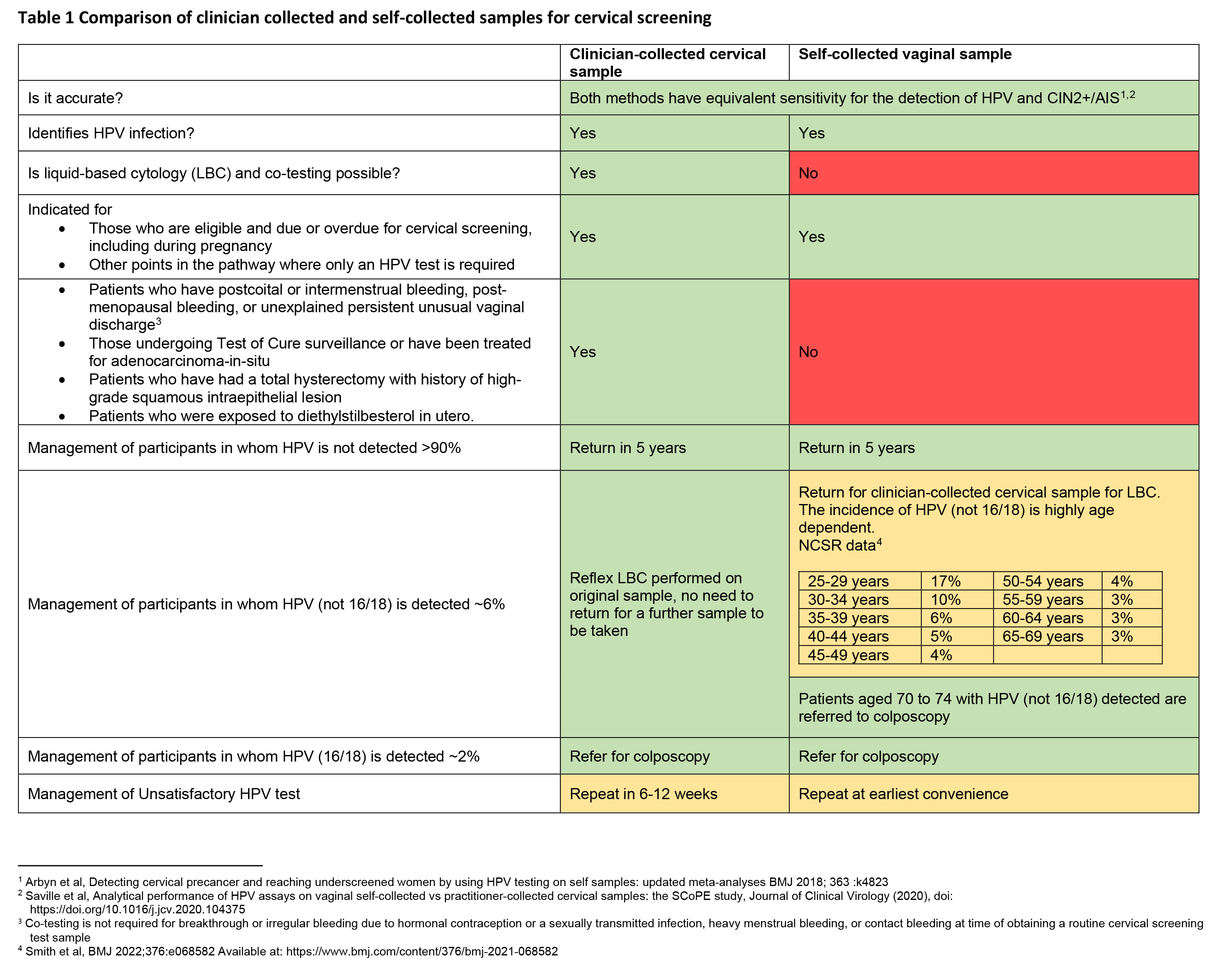

Self-collection with a vaginal swab is used to detect oncogenic HPV DNA but, because the sample does not include cells from the cervix, it cannot be used for cytology. As a result, anyone requiring a co-test (testing for HPV plus liquid-based cytology [LBC] on the same sample) is ineligible for self-collection, whereas at any point in the NCSP where an HPV test is required, self-collection can be used.

Principally, anyone with a cervix who is due or overdue for screening within the NCSP is eligible for self-collection, including during pregnancy of any gestation. Antenatal consultations can be an ideal opportunity to provide screening for groups such as migrant women for whom this might be their first opportunity to participate in screening. Participants undergoing follow-up HPV tests following an intermediate risk CST are also eligible for self-collection of their HPV test.

Self-collection is already available anywhere in the pathway that an HPV test is required, and generally supported with Medicare rebates. However, people who have had an initial clinician-collected screening, who now require a follow-up HPV test and wish to self-collect, need to be aware that Medicare rebates will not be available in this circumstance until 1 November 2022 when choosing whether or not to access self-collection during this period.

When providing information to patients, it is essential for clinicians to provide clear information to support informed decision-making around the choice between self- versus clinician-collected sampling. This includes how to take the test, how the results will be received, and information about the advantages and disadvantages of each option, including differences in the management and follow-up of tests that are positive for an oncogenic HPV type (Table 1).

To support inclusion of hard-to-reach groups, the updated guidelines for the management of screen-detected abnormalities in the NCSP (the Guidelines) also support clinicians in providing assistance to patients who may need it because, for example, of a lack of mobility or a movement disorder. Clinicians could collect the vaginal sample without the need for a speculum and this should still be classified as self-collection on the pathology request form.

Given that underscreened people accessing self-collection may be at higher risk, at least initially, of requiring follow-up or referral for colposcopy, individualised support to complete the pathway including sensitive reassurance and explanation, longer appointments or additional follow-up contact and liaison with colposcopy services may be required.

The self-collection pathway aims to address inequities in cervical cancer, and the need for flexibility in where a sample can be taken to enhance screening access has been recognised in the Guidelines. However, flexibility must never be at the expense of quality. Screening with a self-collected vaginal sample must be ordered and overseen by a health care professional who can also provide or ensure timely clinician-collected sampling when, for example, HPV (not 16/18) is detected.

Self-collection, while preferably undertaken in a health care setting, as this guarantees timely return of the sample, can also occur in any setting the clinician considers it appropriate to support participation of an individual who may otherwise remain unscreened. This opens up the possibility of supporting screening via telehealth at home or at a local pathology collection centre for those with difficulties in accessing clinic appointments or who live in remote areas. When the patient is undertaking self-collection at a pathology collection centre following a telehealth consultation, the clinician must have an arrangement with the laboratory to ensure the correct swabs and information to support self-collection are available.

Self-collection also allows for the provision of screening in outreach settings, such as for people with disability in a group home.

Critically, however, in all settings, the requesting clinician takes complete responsibility for providing the correct sampling devices, for ensuring samples are correctly labelled and identified as being self-collected, and for informing patients of their results and ensuring any required follow-up.

Driving equity in the elimination agenda

Implementing this significant policy change and ensuring its success in reducing inequities in cervical cancer incidence and mortality has required a multisectoral approach and community engagement, supported by the Australian Department of Health Self-Collection Implementation Committee (SCIC). The SCIC membership includes primary care, gynaecology, program managers, laboratories and representatives from underscreened groups, including Aboriginal and/or Torres Strait Islander and CALD communities.

Parallel activities have included updates to the Guidelines and National Cancer Screening Register, changes to associated Medicare Benefits Schedule item numbers, development of resources for clinicians, co-designed national and state- and territory-led tailored communication plans for under-screened groups, and the creation of quality and safety indicators for ongoing monitoring and evaluation of the program.

Given that that almost three-quarters of cervical cancers in Australia are diagnosed in individuals who are under- or never-screened, universal access to self-collection could overcome many of the barriers preventing participation in the NCSP. Self-collection is the potential gamechanger to increasing screening participation. We urge you to play your part in achieving equitable elimination of cervical cancer in Australia by identifying underscreened patients in your practice and letting them know about the option of self-collection.

Professor Deborah Bateson is Professor of Practice at the Daffodil Centre, University of Sydney, a joint venture with Cancer Council NSW, and Chair of the National Cervical Screening Program Self-Collection Implementation Committee.

Professor Marion Saville is a pathologist and Executive Director at the Australian Centre for the Prevention of Cervical Cancer, and Chair of the Working Group for the National Cervical Screening Program Guidelines for the management of screen-detected abnormalities.

Associate Professor Megan Smith co-leads the Cervical Cancer and HPV Stream at the Daffodil Centre, University of Sydney, a joint venture with Cancer Council NSW, and has served on several government advisory groups relating to cervical screening.

The statements or opinions expressed in this article reflect the views of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official policy of the AMA, the MJA or InSight+ unless so stated.

Subscribe to the free InSight+ weekly newsletter here. It is available to all readers, not just registered medical practitioners.

If you would like to submit an article for consideration, send a Word version to mjainsight-editor@ampco.com.au.

more_vert

more_vert

Excellent initiative and not so invasive for women

Excellent initiative