THE main objectives of the Regional Medical Specialists Association are to provide a forum for non-metropolitan specialists to discuss ways to improve conditions and equipment available, to encourage the highest standard of medical practice in regional areas and to assist in recruiting specialists to regional areas.

The first meeting of the RMSA was held in Canberra in May 2018, with attendees from Queensland, NSW, the ACT, Victoria and Tasmania. The second conference was held in Toowoomba, Queensland, in May 2019, and was very well attended. No conference was held in 2020 because of the COVID-19 restrictions, but the next conference will be held on 29 May 2021, in Orange, NSW. RMSA is an active member of the National Rural Health Alliance.

About 28% of Australians live outside major metropolitan centres, yet the proportions of doctors living and working outside metropolitan areas is much smaller. This disproportion becomes stark when considering specialists.

Data from the Royal Australasian College of Physicians (RACP) shows that the maldistribution of practising physicians is mirrored by a maldistribution of trainees. As of 30 June 2019, 6746 trainees were placed in major cities, 386 in inner regional areas, 239 in outer regional, 12 in remote and none in very remote areas.

This pattern of maldistribution probably occurs in all of the surgical disciplines and psychiatry, although paediatrics has many vibrant regional training programs.

Specialists who live and work in regional Australia find it hard to understand how our metropolitan colleagues can’t see the advantages that we enjoy. We are part of a real community that is grateful for our presence and welcomes us into its embrace. Not much of our time is spent travelling, so we go straight from work to leisure with very little time wasted on the road. Most of our regional hospitals have a supportive culture among colleagues. Continuing professional development is easy to maintain through in-house journal clubs, grand rounds and other clinical meetings. Life is good, real estate inexpensive and fresh food plentiful.

GPs provide most medical services to non-metropolitan patients. However regional centres in Australia must maintain general hospitals, staffed around the clock by specialists in various disciplines. The smaller hospitals rely on general physicians, general surgeons, general paediatricians and obstetricians/gynaecologists. Medium-sized to large regional hospitals can also support orthopaedics, oncology services, renal dialysis and mental health facilities.

But how to sustain such services when the majority of Australian medical graduates choose to live and work in the metropolitan areas? There is a limited future for specialty services without a continuous flush of trainees to refresh the workforce. Clearly this is not happening.

Our universities produce more medical graduates than most other OECD nation, yet our rural health services remain dependent upon international medical graduates (recruited from nations that can ill-afford to lose them) and the transient locum workforce.

The solution to this challenge must surely be to train our own specialists in the regions. It sounds easy, doesn’t it? It certainly is the aim of the Commonwealth’s Rural Health Multidisciplinary Training Program, and more recently the Integrated Rural Training Pipeline for Medicine (IRTP).

The IRTP was established by the Commonwealth in its 2015-16 Mid-Year Economic and Fiscal Outlook statement. It is made up of three elements:

- the regional training hubs, which are there to support and coordinate training of specialists in regional areas. Supervision and assessment of trainees remains the province of the Learned Colleges, usually employed by the public hospital system;

- the rural junior doctor training innovation fund, which provides Commonwealth funding to support terms in rural general practice for interns and resident doctors; and

- extra places quarantined in the Specialist Training Program (STP) for trainees spending at least two-thirds of their training time in non-metropolitan locations.

These interventions are backed by high-quality qualitative research in Australia and overseas. People born in rural areas are more likely to return to practise in a rural area. Medical students who spend a year or more in a rural clinical school are more likely to return to practise in rural areas. This also applies to graduates who complete their internship or at least a year of their post-graduate training in non-metropolitan centres.

It’s cheap and easy to blame the Learned Colleges for the lack of trainees in regional areas. The frequent, rather clichéd explanation offered is that the city professors want to keep the best and brightest on a short leash. The reality is in fact far more complex.

By the time a medical graduate is ready to enter specialist training they have spent years in a metropolitan university or teaching hospital, in most cases. Even those who were born in rural areas are conditioned to plan a future in the city. If they have met and married a city person, the partner is far less inclined to take the adventure to go rural than the other way around.

Accreditation of specialist training positions in rural and regional areas is difficult. In anaesthesiology for instance, a particular case mix of surgical operations is needed for the anaesthetist to have all the skills quite rightly required by the College. In many medium to large regional areas, this full case mix is available, but only some of them in the public hospital system. Private hospitals and privately practising specialists have difficulty allocating time for teaching and supervision, and this time is not usually remunerated.

The STP was originally designed to provide Commonwealth funding for specialist training in non-traditional metropolitan public hospital settings. Although rural settings are a good example of the above, metropolitan private hospitals, pathology laboratories and radiology practices were in a much better position to snap up these STP grants than rural hospitals.

The quarantined rural-based STP grants may help this, despite the constant case-mix challenge. Most of the Colleges are well aware of the inequity of health care that specialist maldistribution causes. They are genuinely trying to increase regional-based training, but the unpredictable case mix as well as the financial fragility of regional hospitals works against their best efforts.

The establishment of rurally-based “end-to-end” medical schools and the IRTP together provide the best opportunity to make progress.

This package was proven successful in the Northern Ontario School of Medicine in the last decade. Local high school students, including indigenous students not able to leave their own country, can now aspire to a career in medicine, thanks to a local entry-level medical school. Graduates can buy their first home during their rural hospital internship.

The regional training hubs will help provide innovative solutions to accreditation of more specialist training posts. In 10 years, we can hope that local communities will start to welcome their own back as local medical specialists.

“But the bush hath moods and changes,

as the seasons rise and fall,

And the men who know the bush-land

– they are loyal through it all.”The Bulletin 23 July 1892. In Defence of the Bush

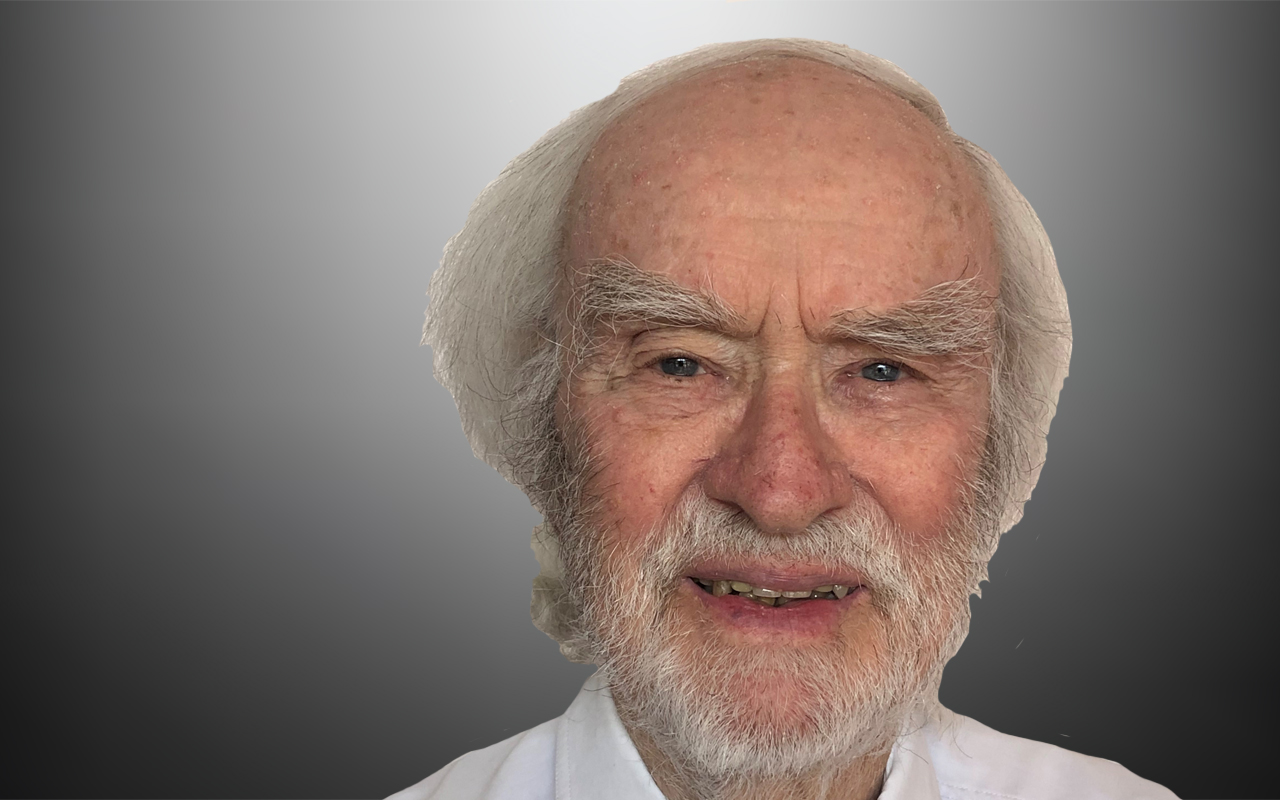

Dr Peter Hughes is a urologist based for over 50 years in the ACT. He is currently President of the Regional Medical Specialists Association. His email address is hughespd@grapevine.com.au

The statements or opinions expressed in this article reflect the views of the authors and do not represent the official policy of the AMA, the MJA or InSight+ unless so stated.

more_vert

more_vert

The problem is multifaceted.

BPT’s only get 13 weeks in regional rotations!

Very hard to get the Advanced Trainee position accredited.

This leaves specialist to work on their own with little junior doctor support -greater chance of burnout and frustration and

Eventually move to the city.

The work environment and job challenges are so different to metro hospital but the rules are the same and the pay is the same!

COVID only made thing worse in rural areas due to both Professional and Social isolation!

Need some fundamental structural reforms in the health system for rural hospitals to get a better share of the specialists.

Totally agree with Kim. And anonymous is partly correct about the education issues. My personal experience of been a solo doctor for a large part of outback QLD, was exhausting but so worthwhile. My leaving this hugely rewarding vocation was triggered by the need for ongoing education of our girls – I couldn’t bear the thought of sending them to boarding school ( like most of the local families) and seeing even less of them growing up.

Rural work has so many work and lifestyle attractions.

But for several colleagues, the deal-breaker has been the planned or unplanned need to meet the high-schooling needs of their teenage children.

Many can make the rural choice for their own lives, but not feel they can deprive their kids of the best education that can be found, which is not always available in rural regions (great though some schools can be).

Australia is world-leading in recruiting specialists to rural areas and draws on Specialists from all over the world to do the harder, lower-paid yet more rewarding work that most Australian doctors shun.

Yet it is also world-leading in making sure those Specialists, who provide 50% of rural services to our population, are not accepted, acknowledged or treated as colleagues, let alone specialists, instead being described variably as ‘IMG’s, ‘OTD’s or AMC’s if they managed to climb the impossible hurdle of passing that vicious exam.

Little chance to ever become a colleague or ‘Specialist’ though, no matter for how many years you’ve formed bonds, looked after people and maintained health in the bush – you will invariably run out of time or steam or just give up because the system is too skewed towards Australian doctors to allow any international doctors a fair run.

Once we change that we’ve got this problem fixed – yet cashed up city colleges and Australian Specialists do not want that competition .

The deliberate (confected) lack of interested specialists, especially engaged & interested ones, within the most senior positions within the public health sphere + the complete lack of recognition of a monetary value for training, supervision & mentoring of younger medical practitioners by older ones are the 2 major issues that need to be addressed.

Both of these issues face barriers beyond the ability of our society, our bureaucrats, our politicians and our media to understand.

It will take major societal shifts in attitude to create the necessary change.