THE COVID-19 pandemic has exposed the enduring undersupply of and excess demand for mental health services. But crisis brings opportunity. The promised new National Mental Health Agreement must put in place the infrastructure to enable the right mental health care to be available where you live, for the first time. It will require a response that invests in people and technology as key to Australia’s future mental wealth.

By way of context, mental health’s share of the total health budget was 7.25% in 1992–93 when the National Mental Health Strategy began, and 7.48% in 2018–19. Repeated inquiries offering hundreds of recommendations have got us nowhere. At the same time, there is evidence that the prevalence of mental illness has increased, particularly among some age cohorts.

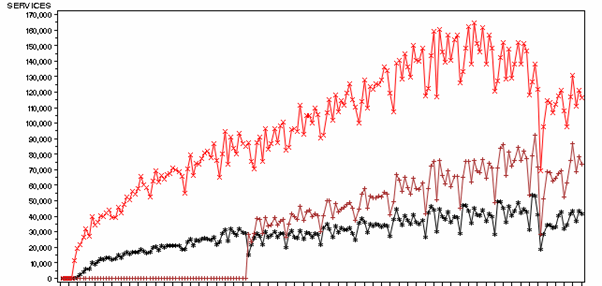

Figure 1 below demonstrates that GPs are, of course, key players in mental health care, particularly through the Better Access Program. Three key Medicare items alone account for 29 million services, costing almost $2.3 billion since the Program began in 2006.

Figure 1 – GP Better Access Program Mental Health Services July 2006 – June 2021

And while recent dips in service numbers can be attributed to the COVID-19 pandemic, the introduction of new telehealth services has compensated. Just over 1 million GP mental health treatment plan services have been provided by phone in the 2 years to 30 June 2021, at a cost of $82 million.

Figure 1 highlights a persistent problem with the Better Access Program, in that only around half the mental health treatment plans written are ever reviewed by GPs, meaning consumer outcomes and progress is not well understood.

The question of how best to meet the primary mental health care needs of Australians is vital. The Australian Institute of Health and Welfare reports that 2.73 million Australians received a Medicare-funded mental health service in 2019–20. The main response to the recent Productivity Commission report into mental health by the federal government was to promise a new Intergovernmental Agreement on mental health by November 2021. This work is being done now, although not, it seems, with the active engagement of GPs, other health professionals or consumers and their families.

Will this Agreement look like all previous mental health plans as top-down, inflexible and lacking real-world implementation? Or will it seek to genuinely engage professionals and communities in decision making about how they respond to their local mental health needs?

This was a key recommendation made by the Productivity Commission, in recognition of the limitations and failures of previous mental health plans. Over the past 30 years, and in addition to all the inquiries, reviews and reports, Australia has had two policies, five plans, one roadmap, one Council of Australian Governments’ Action Plan, among many other documents. And that national planning activity is mirrored at the state level. Yet, and fundamentally, there is precious little evidence to suggest that the mental health outcomes of Australians have improved, or that the incidence of mental illness has decreased. Especially in the light of the pandemic, there is evidence the reverse may be the case – things are getting worse.

The Better Access Program is emblematic of a one-size fits all, centralised and top-down approach to planning and delivery of mental health care in Australia. GPs and other professionals work within an unhelpful model of payment and service that does not permit them to work effectively and makes collaborative mental health care less likely. A key element of future planning must be for governments to explicitly consider how to introduce choice and incentives to free up providers to innovate, encourage client choice and service innovation. GPs are best placed to coordinate complex mental health care. They need to be rewarded for this work, helping to keep people with mental illness well in the community.

We are not advocating entirely open or poorly regulated free markets. In many areas of health care, free markets fail given asymmetric information between provider and clients, potential for moral hazard and supplier-induced demand within the fee-for-service funding models, and the inevitability of incomplete contracts and risk sharing between client and provider. Mental health is more susceptible to these issues, given that increasing levels of distress and the impact of mental health legislation can impact the capacity of consumers and their families to participate in decision making. The introduction of choice and innovation needs to be appropriately managed and well regulated.

It is a paradox that this kind of approach has been taken already (to some extent) under the National Disability Insurance Scheme but only for those people with the most severe or persistent problems, least likely to have cognitive abilities to make informed choices. From an economic lens, choice is only fully beneficial when there is rationality in decision making. We advocate for extending choice to all patients, including those with less severe mental health problems and where the most value and innovation can be generated to prevent and mitigate severe illness.

At the moment, consumers find it very difficult to know which GPs are good at treating mental illness and which psychologists have the right skills and training to address their individual needs. GPs in turn must fit into the strictures of fee-for-service Medicare, aware that they are likely to only review 50% of the mental health plans they write. There is no way for consumers, families or indeed taxpayers to understand the impact of all this work.

Following the Productivity Commission’s recommendation, there is a need to invest in the planning process itself to empower regions to design, prioritise and implement local approaches. Simply providing more funding for a dysfunctional system is unlikely to deliver value for money. The federal and state mental health planning process should focus on stewardship and regulation to create the financial and institutional conditions for successful regional planning. This would commit to balancing funding according to need and overcome wide regional inequities, a regulatory framework that oversees the introduction of choice and quality control mechanisms, and investment in data analytics to monitor, evaluate and provide regular public accountability for performance. Consumers should have a say in whether their outcomes or expectations were met.

Nothing will happen to fundamentally shift mental health care in Australia unless work is done to properly equip local communities to take charge of their own mental health.

GPs and other health professionals need to be at the forefront of helping this happen.

Dr Sebastian Rosenberg is Senior Lecturer at the Brain and Mind Centre, University of Sydney and Fellow at the Centre for Mental Health Research, Australian National University.

Professor Kenny Lawson is a health economist and co-Lead of the Brain and Mind Centre’s Economics, Social Science and Implementation stream.

Professor Ian Hickie is Co-Director, Health ad Policy at the Brain and Mind Centre, University of Sydney.

The statements or opinions expressed in this article reflect the views of the authors and do not represent the official policy of the AMA, the MJA or InSight+ unless so stated.

more_vert

more_vert

There are numerous reports of corruption with funding in marginal seats, from car parks to various amenities etc. How could we guarantee that Medicare Local funding is immune to this? I’d fear that localised funding would be mysteriously more plentiful in marginal seats. Keep it national – we have nationalised measeures in health to determine a person’s needs. This is adding another layer of bureaucracy, for which funding has to come from somewhere.

‘Mental Health Consumers’? Was there ever a more dreadful label. Econospeak prevails.