THE standard approach to valuing clinical interventions for public funding is cost-effectiveness analysis, which estimates the financial cost required to achieve improvements in health. Products are evaluated for inclusion in the Medical Benefits Schedule (MBS) based on the costs of achieving improved quality of life and the number of years lived. Other criteria, such as the overall impact of inclusion or on paid work, are considered.

In a climate of resource constraints, the use of these criteria can be valuable for Medicare and other health care funding agencies around the world for prioritising medical care spending. However, reliance on traditional cost-effectiveness approaches alone may discriminate against interventions targeting elderly populations, who have lower average life expectancies than their younger counterparts. Productivity assessments focused on economic returns from paid work also act against the elderly, given Australia’s low work participation rate of just 13% in those aged over 65 years.

Employment-linked productivity gains offer little insight compared with potential quality-of-life improvements. This issue will only become more problematic as the population ages. Therefore, our economic assessments need to move away from traditional models to those which evaluate the overall contribution to society by the elderly, particularly in unpaid work.

The Australian Institute of Family Studies has shown that older Australians significantly contribute to the care and wellbeing of their grandchildren, either as co-residents or when living separately. In many cases, this childcare support enables their own adult children, typically mothers, to re-enter or remain in the job market. In fact, grandparents represent almost one-quarter of care providers for children below the school-going age.

These societal contributions are not solely in childcare either. Almost 23% of unpaid care for people with disability or chronic conditions is provided by those over the age of 65 years. Furthermore, the volunteer market is strongly reliant on the elderly population, with almost 670 000 older Australians volunteering their time at various organisations.

Just how much of an impact will putting a monetary economic value on the contributions of the elderly to childcare, adult care, and voluntary activities, make to the estimated economic impacts of illness? One recent study from the Baker Heart and Diabetes Institute (Marwick and colleagues) provides some guidance about the potential implications of accounting for the unpaid contributions of the elderly.

The study analysed data from two long-running surveys in Australia, the Household Income and Labour Dynamics in Australia (HILDA) and the Australian Longitudinal Study on Women’s Health (ALSWH) to compare the economic value of paid and unpaid contributions of older Australians with severe heart disease and those without.

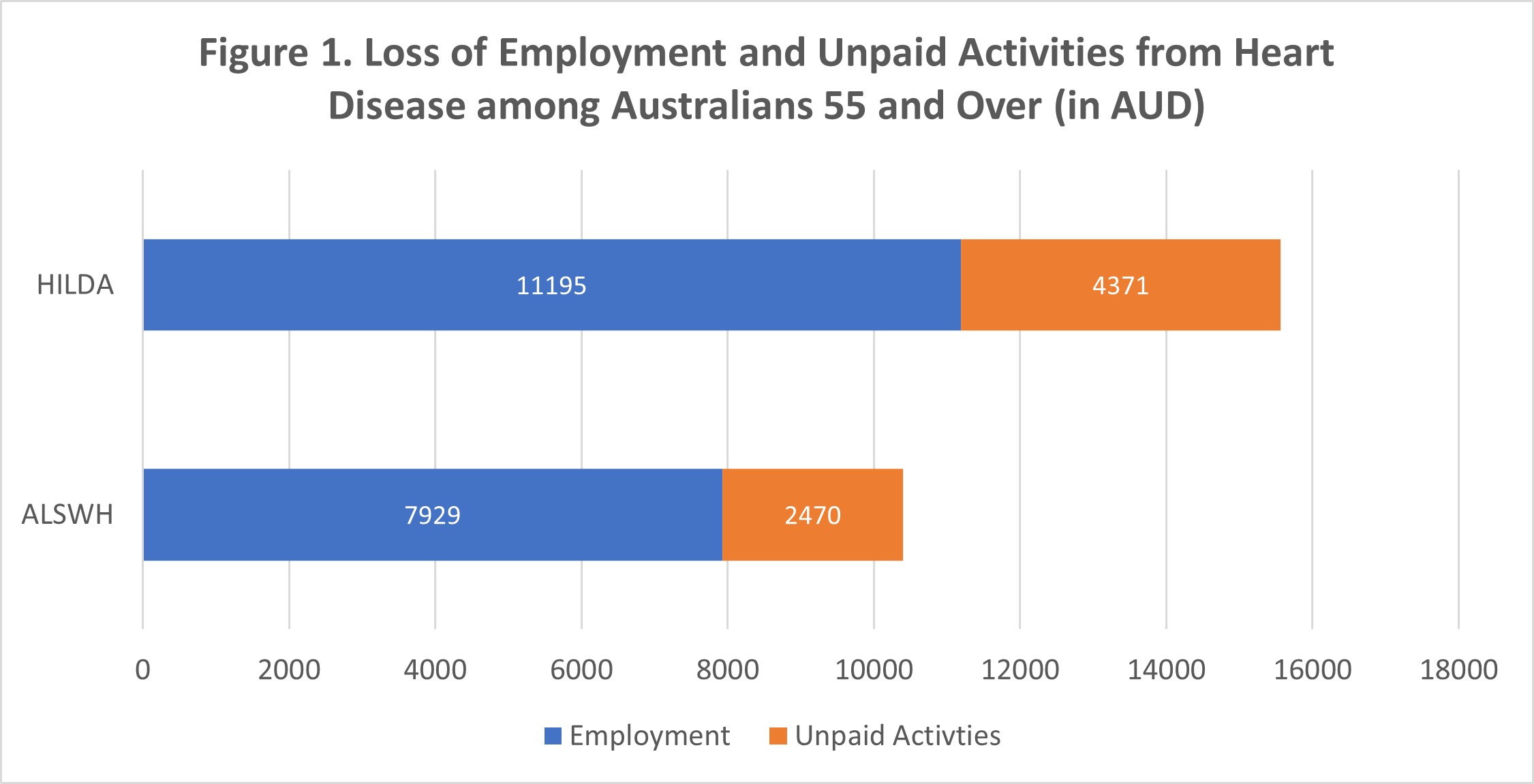

Results from the Marwick and colleagues study showed that based on the accumulative contributions from childcare, adult care, and voluntary work among Australians 55 years and over, the onset of severe heart disease would reduce the value of non-market contributions of the elderly by an amount ranging from $2394 to $4837 annually.

In effect, only focusing only on employment-related effects and not accounting for unpaid activities would lower the impact of heart disease on the economic losses among people over 55 years of age by between 24% and 28% (Figure 1).

Note: AUD = Australian Dollar; HILDA = Household Income and Labour Dynamics Survey in Australia; ALSWH = Australian Longitudinal Study on Women’s Health. Data from Tables 6A and 7 in Chapter 5 of Marwick et al (2021).

As a rough approximation then, interventions that can help reduce the incidence of heart disease among older individuals are likely to lower economic losses by a magnitude that is between 24% and 28% higher than if unpaid activities were excluded.

One could make an argument for an even larger effect on unpaid activities, and hence the value of economic losses for people aged over 65 years. This is because the Marwick and colleagues study focused on people aged 55 years and older, many of whom (those aged < 65 years) are likely to allocate significantly more of their time to paid work than to unpaid volunteer activities. This Australian research, together with similar findings recently produced for Europe, provides a way to better capture elderly contributions to society.

Given the economic value embedded in unpaid work is relatively large, if the list of criteria used to determine items in the MBS schedule were to be expanded to include changes in time allocated to unpaid work, there may be more priority given to interventions benefitting the elderly. One such example would be transcatheter aortic valve implantation for the treatment of symptomatic severe aortic stenosis in lower risk patients.

For the practitioner on the frontlines of care, these findings may not come as a surprise. Nor surely to their elderly patients, for whom their own unpaid contributions are potentially a source of personal satisfaction quite separate from any social value addition.

Therefore, more attention and focus need to be directed towards underused interventions that could help unlock the socially productive capacity of the elderly. These could include interventions that treat heart valve disease that, left untreated, could impose major mortality risks. Moving beyond heart disease, one could also envisage high social yields from greater GP attention to promote treatments for hearing loss among the elderly, another condition where intervention rates are low, and which is known to be a risk factor for dementia.

Financing matters; thus, longer run efforts by GP and patient groups should involve encouraging the Medical Services Advisory Committee (MSAC) and future MBS taskforces to consider broader social contributions when prioritising interventions to be listed under the MBS.

Ajay Mahal is Professor of Health Economics and Global Health Systems Research, and Deputy Director of the Nossal Institute for Global Health at the University of Melbourne.

Marie Ishida is a public health researcher with a Master of Public Health degree from the University of Melbourne. She has research experience in health economics of non-communicable diseases and maternal and child health. She is currently working as a Research Assistant at the Nossal Institute for Global Health and a Lead Epidemiologist in the COVID-19 response at the Victorian Department of Health and Human Services (DHHS).

Teralynn Ludwick is a public health/global health researcher with a focus on health systems and health services research and evaluation. She is currently working as a Teaching and Research Associate at the Nossal Institute for Global Health and the Melbourne School of Population and Global Health.

The statements or opinions expressed in this article reflect the views of the authors and do not represent the official policy of the AMA, the MJA or InSight+ unless so stated.

more_vert

more_vert

I have an issue with the whole concept of “The Elderly”.

I went to England to become a Geriatrician in the early 1970s. It was a new Specialty in the UK, and only just being recognised in Australia as a legitimate sub-specialty of General Medicine. I began to study Demography. In their infancy, Geriatric Medicine and Gerontology divided the population of a country into three groups: Age 0-14, The Young Dependency Group; 15-64, Working Group; and 65+, The Old Dependency Group.

Now, it seems that at 65 we become members of a different species, such as Neanderthals or Cro Magnon Man, and can no longer be treated like any other adult. We have forgotten the famous bell-shaped curve, that whatever characteristic we look at in a population, there is no sharp dividing partition that separates us into two homogeneous halves.

I now believe that there is only one legitimate specialty based on age. That is Paediatric Medicine which is generally defined to cover the period from infancy to the age of 18 years. This is the period in which we grow and develop to maturity in every way including neuropsychologically. Even here, the margin is somewhat blurred. One of my classmates in Grade 7 was as tall as an adult and played as an unbeatable ruckman at footy. More often, some take a long time to develop executive function and controlled adult behaviour.

The population is made up of unique individuals in unique circumstances and predicaments. The partition is bureaucratic, not biological, and any arbitrary groupings are inevitably discriminatory, on both sides of this Iron Curtain. In many situations, the Governments of even the Welfare States of which we purport to be one, make decisions for economic reasons and pretend that they are acting for the greater good.

As someone who has been a son, a young adult, a husband and father, a grandfather, and now a great-great-grandfather, a doctor, and a patient I can empathise with my patients

The authors of this excellent paper are obviously aware of all these points, and I thank them for steering me towards valuable evidence that I will arm myself with for my continuing battle with the mindless bureaucracy that administers our Healthcare System, Aged Care System, and NDIS.

Naturally I agree wholeheartedly as I am 92 years ofd! I had a secondary melanoma sixteen years ago, and still am active in supporting a number of good causes.