IT is a challenge for health professionals to fully acknowledge and “see” sexual, domestic and family violence affecting our colleagues, friends and patients. We like to “other” this problem, to think of it as the statistic we see on the news – the death of another woman, a child removed from care of a parent, or a rape by a stranger late at night – rather than what could be happening to the person next to us or even within our own relationships or families.

How should we as health care workers seek to understand what is abusive behaviour and what isn’t?

Twenty five years ago, I did a doctorate on the nature of domestic violence showing that abusive behaviour is more than physical violence, involving the more hidden issues of emotional abuse and sexual violence. There has been a rich scholarship on this topic, and we have known for many years that abuse is not just physical violence.

Our understanding of what constitutes domestic and family violence has continued to evolve since then. New descriptions of the abuse of power in relationships are playing out with different mechanisms. We now have “technology-facilitated abuse”, “reproductive coercion”, “financial abuse”, “mental health and substance use coercion”. I could go on. While each may seem like new phenomenon with new names, they in fact share old commonalities, reflecting that abuse is a pattern of behaviour using multidimensional tactics rather than a single incident. Specifically, both grooming and coercive control are patterns of behaviour involving power differentials and, although involving different age groups, are the core of the abuse that happens from people that we know, in our homes, schools and sporting groups.

Grace Tame, the 2021 Australian of the Year, recently outlined the six steps of grooming of a child for sexual abuse in her address to the National Press Club, drawing on her own experience of abuse at the hands of her teacher. These stages are: targeting a victim, gaining trust, filling a need, isolating the child, sexual contact, and maintaining control. Jess Hill in her book See what you made me do: power, control and domestic abuse describes that “coercive control” is the main tactic many domestic violence perpetrators use in relationships.

People who use coercive control tactics tend to follow the same stages of grooming. Perpetrators often target vulnerable women, initially gaining trust, filling a need for belonging and trusting someone, isolating women from others, then the abuse begins, continues or becomes more severe and is maintained through controlling tactics.

Elizabeth McLindon and our team at the Safer Families Centre have also shown how prevalent abuse and violence is among us as a group of health professionals. The research shows that, if we include child abuse, almost half of the health professionals we work with may have experienced some form of abuse. These survivor health professionals, the evidence shows, “go the extra mile” to identify and respond to survivor patients.

The gendered nature of abuse and violence is well established. For instance, if we extend abuse to include sexual harassment, more than 85 % of women and 57% of men in Australia will have experienced it during their lifetime. It is all around us – especially for women.

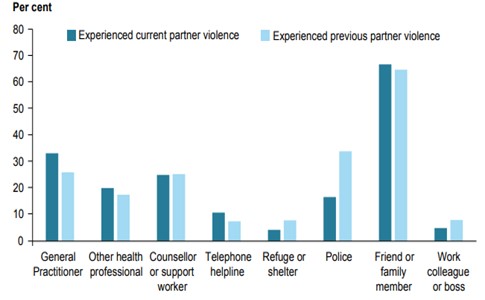

Figure 1. Source: Australian Institute of Health and Welfare at https://www.aihw.gov.au/reports/domestic-violence/family-domestic-sexual-violence-in-australia-2018/summary

Statistics aside, it is important to consider the implications of how different genders view safety. Who are we afraid of in our society? What does it mean to be safe in our community as a person who identifies as a woman, as a man, as non-binary, or other-gendered?

I do an exercise asking medical students and doctors about what they do in their daily lives to keep safe. Men in the audience usually ponder (and ponder some more) as if they have never thought about it and then say “keep away from drunk men”. Women tend to answer immediately and have a long list of regular behaviours they undertake (eg, holding their car keys between their fingers, letting people know where they are, walking only in lighted areas, to name a few). This is a damning indictment of our community, to the extent that some female colleagues I know will not go out by themselves at night at all. This is despite the fact that they are more likely to be sexually assaulted by someone they know than by a stranger.

If we explore experiences for people of diverse backgrounds then the levels of family violence are higher for people who are Indigenous, with racism intersecting with personal experience of violence, compounding the effect. For those people identifying as lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, intersex or queer, experiences of transphobia and homophobia exacerbate abuse and mental health load. Such intersecting identities and experiencing historical and current trauma can be overwhelming.

What should we be doing as health professionals?

Health practitioners are the largest group told about domestic violence in Australia (Figure 2). Yet many health professionals don’t even recognise it in their patients – preferring to deal with biomedical issues only, overlooking this major social cause of ill-health in the community (here and here).

Figure 2. Source: Australian Institute of Health and Welfare at www.aihw.gov.au/reports/domestic-violence/family-domestic-sexual-violence-in-australia-2018

At Safer Families we are advocating transformation of the health system to respond to abuse and violence to change the trajectory of safety and healing for individuals, families and ultimately the Australian community.

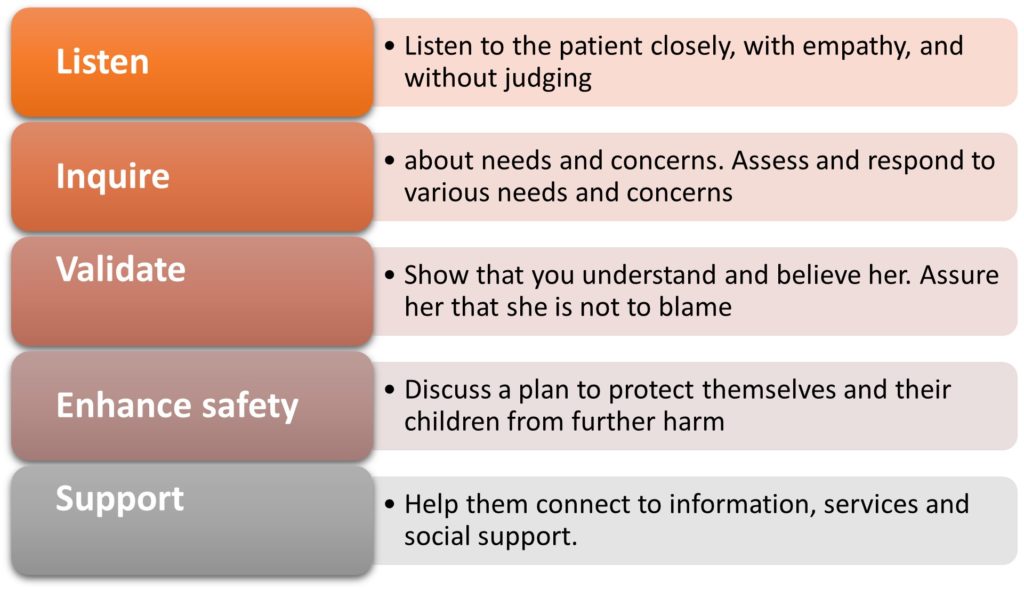

We can make a difference through following the World Health Organization guidance, responding to our patients and survivor colleagues with an evidence-based first line response of LIVES (listen, inquire about needs, validate, enhance safety, and offer support) (Table 1). From our work synthesising what women survivors say they want from health professionals, we should offer survivors CARE (giving people choice and control, action and advocacy, recognition and awareness and emotional support) in clinical practice.

Enacting trauma and violence informed care is essential. This care involves applying principles of safety, transparency, collaboration and empowerment to reduce the power imbalance between health care professionals and patients. Responding in a trauma-informed way assumes that all of our patients have most likely experienced abuse and violence, creating physical and emotional safe spaces to enable disclosure of abuse, and having a deep understanding of the effects of abuse on patients so we can minimise re-traumatisation through the care we deliver.

We can also call out abusive behaviour when we see it if safe to do so and we can motivate people who use abuse and violence to seek help.

Above all, we need to be kind to ourselves, our colleagues and our patients to fully set women, children, young people, and men on a pathway to safety and healing.

Unless we elevate this major public health issue to the point where it receives the investment commensurate with the huge physical and mental health burden that it creates the next generations of children will continue to be unwell.

Dr Kelsey Hegarty is a GP and Chair of Family Violence Prevention, the University of Melbourne and the Royal Women’s Hospital.

If this article has raised issues for you:

National sexual assault support:

- 1800 RESPECT: National sexual assault, domestic family violence counselling service. Operates 24 hours/7 days a week. Phone: 1800 737 732

- Blue Knot Foundation: For adults with experiences of childhood trauma including child sexual abuse. Operates 9am-5pm Monday-Sunday. Phone: 1300 657 380

- Bravehearts: For those wanting information or support relating to child sexual assault and exploitation. Operates 8:30am to 4:30pm Monday to Friday. Phone: 1800 272 831

IF YOU ARE IN IMMEDIATE DANGER, PLEASE CALL 000

The statements or opinions expressed in this article reflect the views of the authors and do not represent the official policy of the AMA, the MJA or InSight+ unless so stated.

more_vert

more_vert

I suppose being retired after 30 years a clinician (rural paediatrician), it shouldn’t surprise me that the naivety in this article exists. Are you really surprised at how much care is required to be safe at night? The death of Eurydice Dixon was caused by a problematic loner probably on the spectrum, with a history of failed psychological interventions, strong self loathing, and an addiction to snuff porn. Such deeply antisocial men exist, and any sensible person takes precautions. No amount of theorising and academic finger-wagging or statistical education will eliminate them. There’s also an excruciating irony: such self loathing often derived from fractured home circumstances, mother fleeing domestic violence, and absent fathering.

I recall a situation I discussed years ago with an experienced country town GP. He detected domestic violence in a young mother, and asked about her sex life. Ever since the last birth, it hurt – something to do with a retained stitch – which he arranged to be removed via an O&G referral. Her husband was drinking too much, and abusing her. (Neither of them knew why sex had become painful). He arranged to see the husband on the pretext of a medical checkup and discussed the REAL issue. Once their sex life was back on track, the violence stopped.

Make of that story what you will, but it speaks to me more about the essence of good doctoring, than mounting crusades; although I recognise their worth

Great article and appreciate things are progressing because of lots of hard work. The intersectional train is pushing truth to the surface, and everywhere people are perhaps seeing the nasty, shapeshifting corrupt power structures. Challenging to see as sometimes are quite stealth and chameleon, they hide behind patriarchy, feminism, government, mental health services, World Health Organisation etc … the emperor has new clothes. Having government staff. And health professionals be one step above the patient, victim, individual is still one STEP in the hierarchy power structures you desperately trying to dismantle. Please consider looking at whole family systems and getting whole family systems in a room together please? Constellation therapy is a pacifier and so is a psychologist. Humans need family groups healing together.

Terrific article. Great summary of issues. Could there be mention of those with disabilities also though? Women with disabilities are at particularly high risk compared to all other groups. Those with certain disabilities such as intellectual disability are at a disadvantage when it comes to advocating for themselves so let’s make sure we include them in the discussion and work out how to decrease violence against them along with all the other increased risk groups for being victimised.

Carers are a group seldom discussed, and often invisible, in relation to ‘domestic’ or ‘family violence’. In mental health, the primary carer is usually the mother of a mature age adult son or, less frequently, a daughter living in the home. The threats of violent assault a carer may experience from a mentally unwell adult child contributes to trauma – and if ignored, or unasked, by clinicians, could be fatal.