PUBLIC health messaging about heart attack symptoms is not getting to younger people or people without a history of cardiovascular disease. That’s the conclusion from experts commenting on a research letter published in the MJA.

The research set out to find out what influence travelling by ambulance had on reperfusion time and outcomes for patients with ST-elevated myocardial infarction (STEMI) compared with patients who made their own way to hospital.

The authors analysed data from 43 hospitals across Australia from 23 February 2009 until 31 December 2017. Of the 2765 patients who presented with STEMI, they found 1616 (58.4%) arrived by ambulance and 1149 (41.6%) by other means.

Interestingly, patients who arrived by ambulance were more likely to have a history of cardiac events.

“The median age of patients arriving by ambulance (64 years; interquartile range [IQR], 54–74 years) was higher than for the other patients (59 years; IQR, 51–67 years), and the proportions with hypertension, a family history of coronary heart disease, or prior myocardial infarction, atrial fibrillation, or stroke/transient ischaemic attack were larger,” the authors wrote.

As a result, the outcomes of the two groups were similar, despite their different risk profiles.

“Despite the less favourable risk profiles of patients who arrive by ambulance, their hospital outcomes are comparable with those of patients who present directly to hospital, presumably because of their more rapid access to reperfusion,” the authors wrote.

Although this finding isn’t novel, according to the Heart Foundation’s Chief Medical Adviser and cardiologist, Professor Garry Jennings, it suggests that more work needs to be done on public health messaging.

“There have been several heart weeks in recent years where the focus has been about presenting to hospital quickly with early signs of chest pain. Clearly, it’s not enough, and it isn’t getting through,” he said.

Professor Jennings said this research shows there are two important messages Australians need to hear.

The first is the symptoms of a heart attack.

“People are not really aware of the potential symptoms of heart attack. While there is a typical presentation, not all people present with acute crushing chest pain,” he said.

Associate Professor William Chan, a consultant and interventional cardiologist affiliated with the University of Melbourne and Monash University, who was not involved in the MJA study, agreed that there was still very low community awareness of heart attack symptoms.

He’s particularly concerned about people in culturally and linguistically diverse areas.

“The Heart Foundation provides some messages in different languages, but the television campaigns aren’t targeted towards those patients. Some of these suburbs have very low health literacy. Targeting these suburbs might help with awareness,” he told InSight+.

Professor David Brieger, Professor of Cardiology at Concord Repatriation General Hospital in Sydney, and the senior author on the MJA article said the same conclusion was reached after the Heart Foundation’s “Warning Signs of Heart Attack” campaign which ran from 2010 to 2013.

“The Heart Foundation campaign message was received more readily by younger and healthier people, which is not a bad thing, but sicker people and people who don’t speak English as their first language didn’t respond as effectively,” he said in an exclusive InSight+ podcast.

While public health campaigns lift awareness of heart attack symptoms at the time of the campaign, they rarely lead to long term awareness.

“When you stop these campaigns, the impact extinguishes, and it’s business as usual. The importance is to maintain the focus on these public health messages,” Professor Brieger said.

The second focus of a public health campaign should be to tell Australians to call 000 as soon as they suspect a heart attack. It’s important to call, even if they think driving to the hospital would be quicker than waiting for an ambulance.

“The most important thing you can do is to call 000 and provide information about your location and be guided by the information you receive,” Professor Brieger said.

“The safest thing to do is wait for care to come to you and in most cases that can happen relatively quickly.”

It’s not just about getting to hospital quicker. Calling an ambulance can lead to a more rapid diagnosis and quicker intervention once you get to hospital.

According to the MJA article’s lead author, Dr Eleanor Redwood:

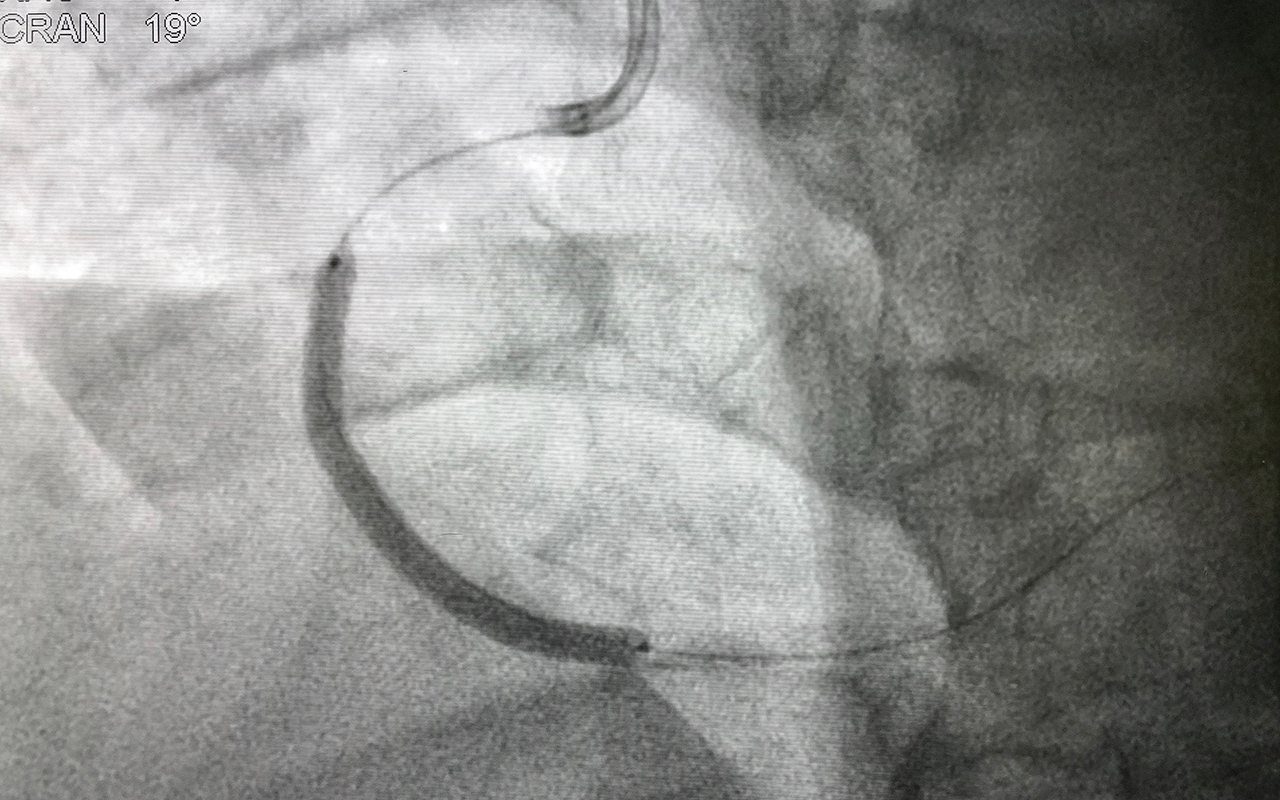

“[STEMIs] can be diagnosed earlier with an [electrocardiogram] by the paramedics in the ambulance. That can allow for a pre-hospital notification of emergency departments to prepare for fibrinolysis. They can [prepare the catheterisation laboratories] for percutaneous intervention so they can be ready to receive that patient.”

There is also the risk of cardiac arrest with STEMI.

“If that occurs when the patient is in a taxi or even driving their own car, the consequences can be catastrophic,” Dr Redwood said.

Ultimately, Australians need to be reminded that it’s better to be safe than sorry with suspected heart attacks.

“It’s not a problem to be taken to hospital and not have a heart attack. We’d rather have those than people who stay at home and don’t have treatment and risk sudden death,” Professor Jennings concluded.

more_vert

more_vert

I think that there is a problem of denial in the sub group of educated males with a strong family history of death from myocardial infarction at a relatively early age. They avoid seeing a GP in case they discover that they are at risk and a significant number of them take up running, cycling, triathlons etc in the belief that will protect them. Despite all the really significant developments in risk assessment, risk reduction treatments and emergency treatments too many middle aged males with a strong family history die similarly of sudden cardiac death.

In Victora, rural ambulances can deliver fibrinolysis enroute to hospital under certain circumstances. This initiative is due in part to the concentration of cath labs in Melbourne and a couple of large rural hospitals.