This article is the latest in a monthly series from members of the GPs Down Under (GPDU) Facebook group, a not-for-profit GP community-led group with over 6000 members, which is based on GP-led learning, peer support and GP advocacy.

IT IS no secret that what, how much and how we tell patients affects not only whether they understand and remember what we tell them but also whether they accept or believe it.

To follow our advice, they must believe it. If they do not believe, they may not start the medication, abandon it or even develop unintentionally self-induced adverse reactions.

Reframing existing knowledge gives us the opportunity to understand the significance of the placebo and nocebo effect.

The placebo effect has been well known for over 300 years as a positive effect on symptoms that occurs from belief in the power of an inert substance. It has also been observed as a positive effect from medication that is active but inappropriate, for example, antibiotics for a viral sore throat. Recently, it has been observed as a positive effect in addition to standard appropriate therapy.

It is my observation that the placebo effect utilises the same mechanisms and descriptions of actions as “empathy” and “good bedside manner”; this also applies to the nocebo effect and “lack of empathy” and “poor bedside manner”. Designated as “good bedside manner” and empathy (here, here, and here) the placebo effect has been seen to improve symptoms and outcomes. This is clear in the different outcomes from male and female physicians.

In comparison, the nocebo effect has been recognised only relatively recently. It is a negative effect, ranging from a blocking of improvement of symptoms to adverse symptoms, triggered by disbelief in the effectiveness of a therapy or belief that a therapy is harmful. While it can occur with an inert therapy (as seen in the “pointing the bone” curse of the Australian Aboriginals of the Central Desert), it was suspected when patients developed unexplainable adverse reactions to medications that were not present when those same people had been taking the same medication, believing it to be a placebo in a double blind trial.

It is now suspected of being responsible for a decrease in good outcomes from standard, appropriate therapy (here, here, and here).

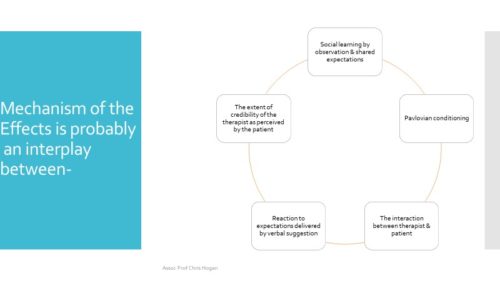

What causes the placebo effect and, by inference, the nocebo effect?

Source: Häuser W, Hansen E, Enck P: Nocebo phenomena in medicine: their relevance in everyday clinical practice. Dtsch Arztebl Int 2012; 109(26): 459–65. DOI: 10.3238/arztebl.2012.0459

To quote from Hall and colleagues (2001): “Trust is critical to patients’ willingness to seek care, reveal sensitive information, submit to treatment, and follow physicians’ recommendations”.

According to numerous studies (here, here, here, here, and here), we can conclude that a doctor’s credibility has five overlapping characteristics:

- Fidelity: caring and advocating for the patient’s interests or welfare and avoiding conflicts of interest;

- Competence: having good practice and interpersonal skills, making correct decisions, and avoiding mistakes;

- Honesty: telling the truth and avoiding intentional falsehoods;

- Confidentiality: proper use of sensitive information; and

- Global trust: combining elements from some or all of the separate dimensions.

There are ways to decrease the impact of the nocebo effect. From studies in chronic pain it is recommended that physicians:

- avoid negative patient–clinician communication and interaction during treatment;

- reduce emotional burden of patients during treatment with analgesic medication;

- reduce and contextualise any negative information provided via informational leaflets;

- have a warm and positive environment that is supportive rather than clinically functional; and

- address the patient’s lack of positive information.

Caveats

There is such a thing as “open label placebo” effect whereby the patient is aware that the substance is inert and yet still experiences a positive effect – although not in the same high numbers.

The placebo effect has been proven to have an impact on a limited number of conditions. The placebo effect does not affect all conditions and when it is active, does not affect symptoms to the same extent. The percentage affected varies from 10% to 80%.

The duration of the placebo effect has not been proven. Hrobjartsson and Gotzsche believe that they are short lived, but they only reviewed randomised controlled trials (RCTs).

Reactions can wrongly be considered to be placebo or nocebo effects. Dealing with the positive results of placebo and the negative consequences of the nocebo effects is a major – and understudied – part of routine clinical practice. Equally significant is the risk of inappropriate attribution of atypical patho-physiological events to them. We can ignore a physical condition and attribute it to the placebo/nocebo mechanism if it makes no sense to us. This is highlighted in the literature on medically unexplained symptoms. The referenced article and its cited references are most illuminating.

The nocebo effect has not yet been proven to occur when a negative effect arises from an active but inappropriate medication.

Our gold standard investigation – the double-blind placebo-controlled trial is actually blind to the influence of placebo effects. The RCT is designed to negate the influence of placebo. To counter the placebo effect RCTs rely on neither the investigators nor participants knowing if they are using an active treatment. However, RCTs may induce nocebo effects. The essential ingredient for informed consent is full disclosure. This constantly raises the doubt that the treatment is active and even if active it stresses the possibility of a myriad of adverse events (here, and here).

It is not enough to make the appropriate diagnosis and provide appropriate therapy. Patient compliance relies on the patient wanting to start therapy and persisting with it. They must believe us. If they do not believe, they may not start the medication, abandon it or even develop unintentionally self-induced adverse reactions.

Placebo and nocebo effects influence communication with patients which is a complex skill well above simple provision of data.

We are obliged to educate our patients, which means assisting them to integrate new information into what they already know or think they know. We need to be interactive and positive with patients in discussing our therapy, as this assists their clinical outcomes, but we need to balance this positivity against full disclosure to ensure the obtaining of informed consent.

Exploration of the placebo and nocebo effects and their clinical significance is just starting and is a field worthy of great attention. This is difficult due to the neutralisation of randomised control trials in their investigation.

Associate Professor Chris Hogan has had many GP involvements including proceduralist, practice principal, GP advocate, researcher and academic. He is affiliated with the University of Melbourne.

The statements or opinions expressed in this article reflect the views of the authors and do not represent the official policy of the AMA, the MJA or InSight+ unless so stated.

more_vert

more_vert

Thank you Oliver for your comments.

Of interest, one of my references is of the opinion that even people who are not suggestible or amenable to hypnosis can still experience the Placebo / Nocebo Effects.

My point was that the placebo effect can be an additional benefit to standard treatment with an active & appropriate therapy

Chris Hogan describes and discusses aspects of care whose positive and unintended negative influences on the outcomes of care are often not recognised. Last year Monica Moore and l explained how learnings from the practice of therapeutic hypnosis inform what we say to patients and how we say it, in order to help them best: https://insightplus.mja.com.au/2018/8/hypnosis-positive-therapeutic-potential-of-a-doctors-words/ .

Chris Hogan says: “The RCT is designed to negate the influence of placebo.” We have come to understand that ingesting or using even a medicine that is known to have no pharmacologically active ingredients often has therapeutic effects. The act of putting a tablet or other medicine into one’s body has a powerful symbolism, representing the acceptance of the doctor’s advice and care. In trials of medicines, the use of placebos therefore cannot be said to constitute ‘usual care’ and the use of a placebo arm in fact does not megate the infleunce of placebo. Studies of medicines should have a third arm that is more truly ‘usual care’, in which the participants are not asked to take or to use any kind of trial medicine at all, but are simply observed. (We need to acknowedlge that even simply being observed as part of a trial is not usual care either).