ON the afternoon of 25 November, 2014, Test cricketer Philip Hughes was batting for New South Wales in a Sheffield Shield match at the Sydney Cricket Ground. He’d reached 63 not out when an attempted hook shot went awry, and Hughes was struck by the ball just below his left ear. He collapsed on the pitch, was given cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR), and was taken to nearby St Vincent’s Hospital. Despite surgery and the best efforts of his doctors, Hughes died 2 days later.

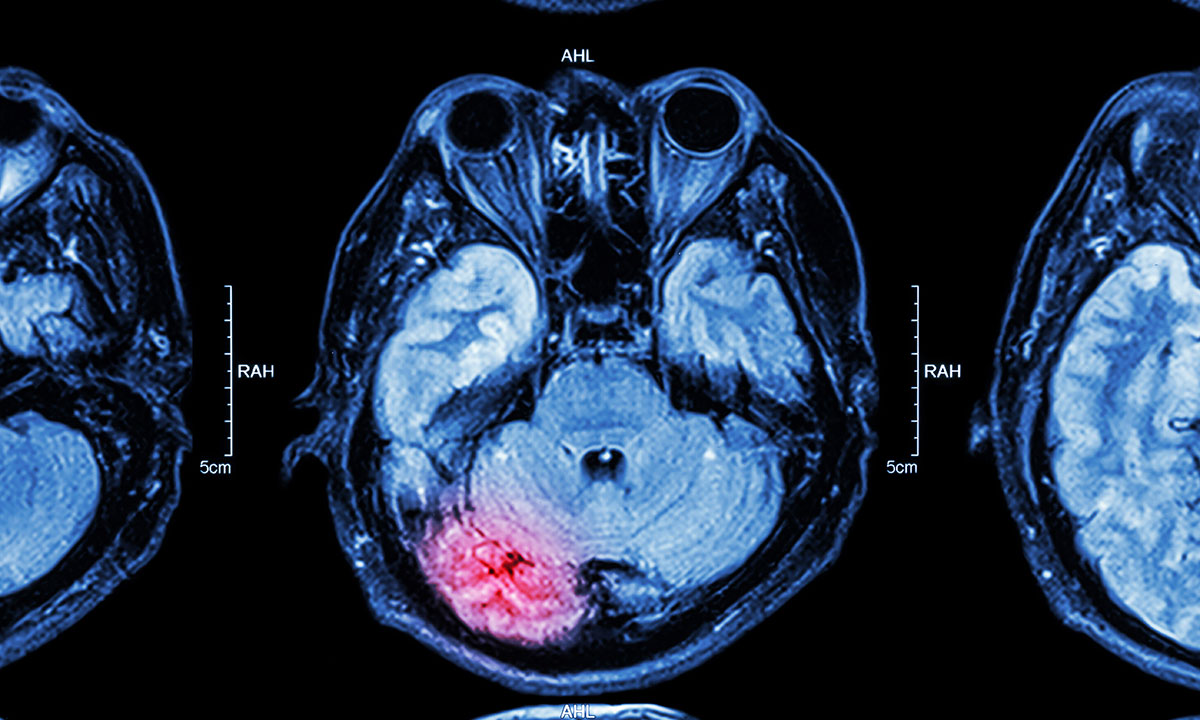

The shock of his death, not just in the cricket world but across the nation, was immense. Peter Brukner, Cricket Australia’s doctor, was at the hospital as Hughes died and it fell to him to explain to the media what had happened. Hughes had suffered a vertebral artery dissection when the ball had struck his neck, he said, which had in turn led to a subarachnoid haemorrhage. “This was a freakish accident,” he said.

But cricket writer Andy Bull took exception to the word “freakish” and, in an article in The Guardian, listed a number of other cricketers who had been killed while playing the game. “The chances of being killed during a match are infinitesimal but the words ‘freakish’ and ‘one-in-a-million’ underplay the very real dangers of the game,” he cautioned.

Intrigued by the piece, Brukner spoke to Bull, who told him that he’d been contacted by an Adelaide historian and cricket nut called Tom Gara, who was interested in researching cricket deaths in Australia. Brukner got in touch and the idea for a research article, now published in the MJA, was born.

Largely using archival newspaper records, the article, authored by Dr Brukner, Tom Gara and Federation University Australia epidemiologist Lauren Fortington, looks at the history of cricket-related fatalities in Australia, from the very first in 1858 through to the tragic circumstances of 2014. All in all, the authors identified 174 cricket-related deaths, around half in formal matches and the rest in informal play (school, backyard and beach cricket). The ages range from the young baby of a spectator hit by a ball to a 78-year-old umpire.

In organised settings, batsmen were the most common victims (45 deaths), largely as a result of being hit by the ball on the head, neck or chest. Eleven fielders have been killed, either from being struck by a ball or colliding with other fielders or the boundary fence. There were also six wicketkeepers (all struck by a ball, except one who was hit by a bat), three umpires, three spectators, and one innocent bystander felled by a ball from a nearby ground. Only one bowler has been killed, struck by a ball during practice.

The peak period for fatalities was in the 1930s and 1940s, after which they began to tail off, before an apparent dramatic reduction from the 1980s on, when helmets were introduced for batsmen. Since then, no cricket-related deaths after a head injury have been reported. In fact, only five deaths, including that of Philip Hughes, have been recorded in the past 30 years. Of those, two were due to vertebral artery dissection, and three were presumed to be due to a condition known as commotio cordis (Latin for “agitation of the heart”), in which disruption of the cardiac rhythm occurs as a result of a blow to the area directly over the heart.

Other than Philip Hughes, there has only been one other documented case of a cricket-related death due to vertebral artery dissection, and eight or nine more cases where, in retrospect, it was the likely cause of death. But helmet manufacturers are taking it seriously as something that needs to be protected against.

“Helmets haven’t protected against vertebral artery dissection, but there have now been some modifications over the past couple of years to protect that area,” Dr Brukner told MJA InSight in an exclusive podcast. “It should eliminate it as a cause of death and I think it will probably become standard in cricket helmets over the next couple of years.”

Once those helmets do become standard, it leaves commotio cordis as the remaining problem in cricket-related fatality. And it’s not an easy one to solve, because the chest guards that some players wear may not be effective.

“The evidence from baseball is that chest protectors don’t seem to help,” Dr Brukner says. “It’s not really the high speed deliveries that cause the problem. They may cause fracture of the ribs, but actually it’s the medium-pace deliveries that seem to cause commotio cordis. It’s the timing rather than the velocity that’s important. If the blow occurs in a particular millisecond of the electrical cycle of the heart, then it will cause sudden ventricular fibrillation that can lead to death. You can be incredibly unlucky, that’s what it boils down to.”

Dr Brukner says the answer is to have people around with CPR training and to have portable defibrillators present at the grounds, with people who know where they are and how to use them.

“That’s the key and that’s the most we can do for commotio cordis. We can still reduce deaths in cricket and make it safer.”

An example of this, and a good news story to boot, is that of Jarrod Brown. In 2012, the 25-year-old Melbourne man went into cardiac arrest after a delivery struck him in the chest during cricket training. The batter collapsed with commotio cordis within 30 seconds of impact and two of his teammates performed CPR on him until the ambulance arrived 9 minutes later. The paramedics found the patient in ventricular fibrillation and delivered a shock that immediately resulted in the return of sinus rhythm. Jarrod made a complete recovery, returned to his job 2 weeks later, and continues to play cricket.

In a case report published in the Lancet, Jarrod’s doctors noted that “the successful outcome was achieved because of early basic life support and defibrillation”.

“Continuing efforts to train coaching staff and players in first aid and ensure timely access to defibrillation should reduce the mortality associated with this condition.”

To find a doctor, or a job, to use GP Desktop and Doctors Health, book and track your CPD, and buy textbooks and guidelines, visit doctorportal.

more_vert

more_vert

i witnessed one rowing death.Elite rower collapsed at the finish of a 2000 meter race Despite two doctors present resucitation was not successful no obvious cause on autopsy

Vilage cricket The wicket keeper was struck on the chest and died.This was in the early fifties and CPR was not prcatised and no medical person was available

i was the wicket keeper for the opposing side!!!

As a wet bob (ex) I wonder if anything similar has been done for rowing. I only know of one incident myself, a sculler who was found drowned.

What an interesting article. What it tells me is that cricket is an exceedingly safe recreational pursuit and is infinitely safer than the drive to and from the ground. That said, I laud the efforts to make it even safer….