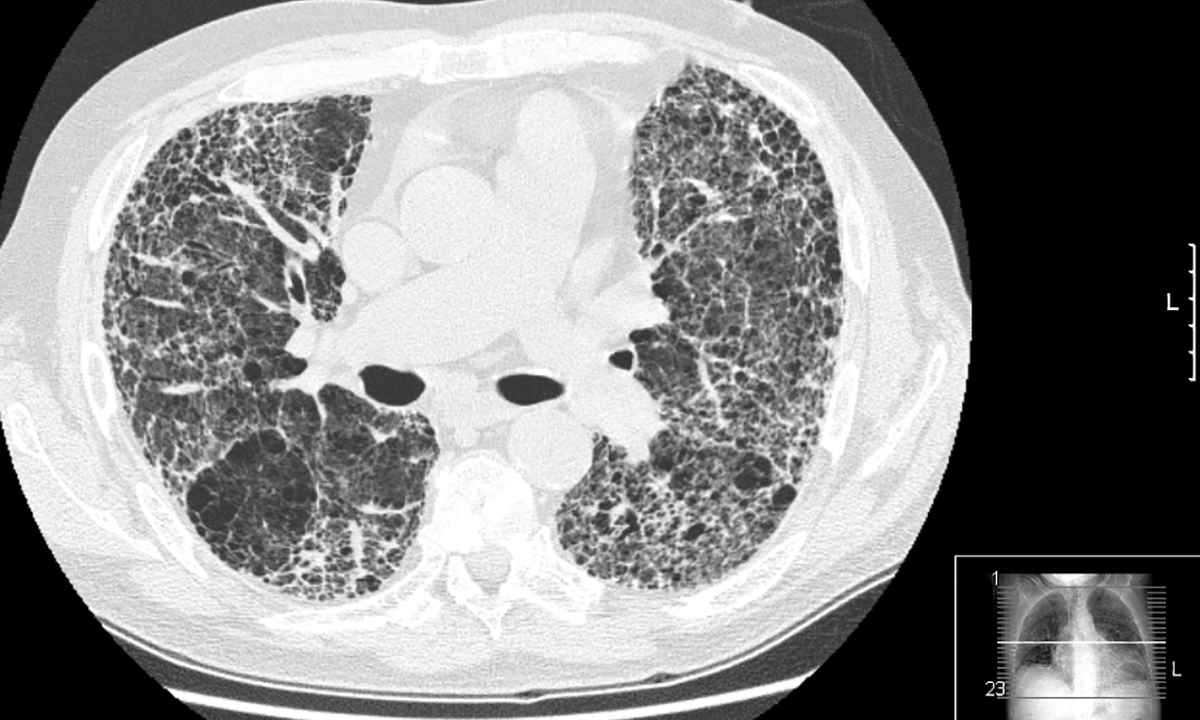

IDIOPATHIC pulmonary fibrosis (IPF), caused by excessive scarring of the lungs, is a particularly nasty disease to get. People with the condition become increasingly breathless and develop a dry, unproductive cough, symptoms which get progressively worse until death intervenes. Patients, who tend to be over the age of 50 years, typically die within 2–5 years of diagnosis.

Until just a few months ago, there were no disease-modifying treatments available in Australia other than lung transplant. But there have been exciting developments in a field where not much has changed over decades. In 2014, the New England Journal of Medicine published two placebo-controlled trials of new antifibrotic agents, nintedanib and pirfenidone, showing that both slowed disease progression by around 50% at 12 months. The drugs were quickly approved in the US and Europe, and were listed on the Pharmaceutical Benefits Scheme (PBS) in Australia in April and July 2017, respectively.

The development prompted new position statements on the diagnosis and management of IPF from both the Thoracic Society of Australia and New Zealand and Lung Foundation Australia, which have been summarised in an article published in the MJA.

Co-lead author, Associate Professor Tamera Corte, a respiratory staff specialist at Sydney’s Royal Prince Alfred Hospital, says the two new antifibrotic drugs represent “a massive breakthrough” in the treatment of IPF, a disease which, as its name suggests, has no known cause.

“The recent PBS listing is why our paper is important, because GPs out there will have never used these drugs, which are now available to anyone with IPF.”

One of the additions to the position statement is a renewed emphasis on the importance of multidisciplinary meetings in the diagnosis of IPF.

“That’s something we’ve focused on in the paper,” says Dr Corte. “The problem is that a lot of fibrosis looks the same, so IPF is very easy to misdiagnose. It’s important to get input from a range of specialists to rule out other possible illnesses, which may look similar but in fact can be much easier to treat.”

Despite the welcome addition of the two new antifibrotics, the only potentially “curative” treatment for IPF remains lung transplant, which Dr Corte says isn’t common enough.

“They’re very effective if they work, but of course there’s always the risk of rejection, so it’s a treatment option with complications. It would be great if we could offer everyone a lung transplant, but there aren’t enough donor lungs. In the meantime, we’ve got to work on other ways of treating this condition.”

Dr Corte says the key to good management is accurate diagnosis and early treatment.

“The message for GPs is to try and identify this condition early and accurately and get the patients on treatment. It makes a massive difference if it’s stabilised at an early stage.”

Professor Darryl Knight, who heads up the University of Newcastle’s School of Biomedical Sciences and Pharmacy, has been involved in IPF research for over 15 years. He says a number of risk factors, such as smoking, have been linked to IPF, although none have been shown to be directly causative.

“What we currently think happens is that somewhere along the lifecycle, there have been multiple microscopic injuries to the lung epithelium, and a normal wound-healing response becomes abnormal and doesn’t shut off.”

He says his team has been working on premature cell senescence, which is strongly associated with IPF.

“What happens is the cells stop dividing, but they don’t die and they stay metabolically active. We know that the cells that produce connective tissue, the fibroblasts, are senescent and so are the epithelial cells, but we don’t know how they impact on each other and that’s what we’re trying to work out.”

Professor Knight says that another aspect to his research is the setting up of a lung biobank, mostly comprising lungs of patients with IPF who have had a lung transplant.

“IPF is a very heterogeneous disease, and presents in different parts of the lung, so if you don’t know where you’re obtaining your cells or tissues from, you can be looking at completely different cell processes. So we need access to whole lungs – that’s the only way we’re going to understand the disease process. That way we can compare tissue from fibrotic and non-fibrotic regions as well as areas of inflammation and tissue destruction.”

Professor Knight says the biobank approach will lead to a clear understanding of normal and abnormal fibrotic pathways, which will allow the development of therapeutic targets.

“In 10 years’ time, we’ll be in a much stronger position, and if we don’t have new therapies already, there will be some that will be very close to being ready.”

Dr Corte says that the success of nintedanib and pirfenidone has sparked much commercial interest, and there are a number of new agents already being tested in trials in Australia as add-on therapies.

“I think that in the future managing IPF will look much like how we manage HIV [infection] today, with combination therapies. One antifibrotic won’t be the answer, there will probably be a combination. The end goal might be that, like HIV [infection], IPF is seen as a manageable chronic disease.

“There is definitely room for improvement, and I’m optimistic that we’ll see that improvement.”

To find a doctor, or a job, to use GP Desktop and Doctors Health, book and track your CPD, and buy textbooks and guidelines, visit doctorportal.

more_vert

more_vert

What is the difference between the condition described here and Pulmonary Arterial H.ypertension?

KBO 20/11/17