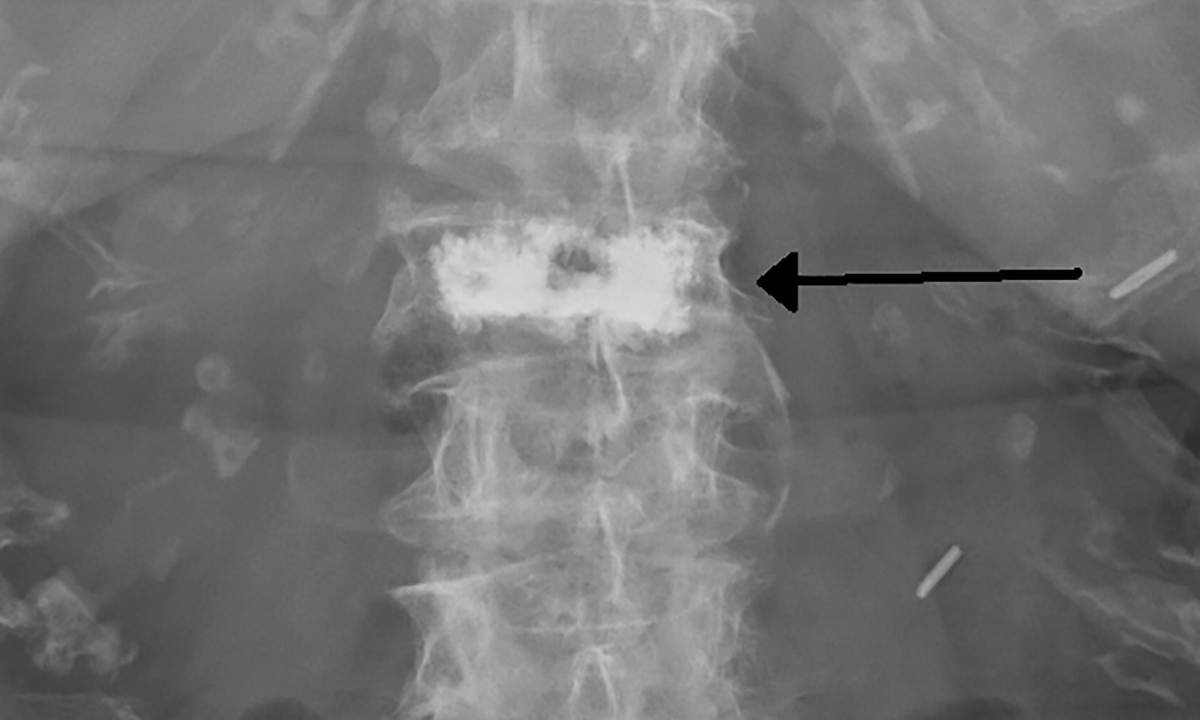

IN 2009, the publication of two pivotal trials appeared to seal the fate of vertebroplasty as a treatment for osteoporotic compression fractures. Initially developed for treating vertebral tumours, vertebroplasty involves injecting liquid cement into a collapsed vertebra, pumping it up to its uncollapsed size to relieve pain and morbidity. Since its introduction in the 1980s, the procedure had become increasingly popular, with good anecdotal evidence for its analgesic efficacy.

Then came the trials (here and here). Previous small studies had suggested some benefit, but these were the first randomised, placebo-controlled trials to be carried out for vertebroplasty, and they both showed no improvement in pain at various time points, compared with a sham procedure. A direct consequence of those results was the removal of the Medicare item number for the procedure, and its appearance on several “do not do” lists. The vertebroplasty era seemed to be over.

But was the medical establishment too hasty in writing off this procedure?

That’s the subject of a new Perspective published in the MJA. Its authors, led by Paul Bird, a rheumatologist in private practice and Associate Professor at the University of New South Wales, say that the 2009 trials do not paint a full picture. They have gone so far as organising their own randomised trial, published in the Lancet in 2016, which does show the efficacy of the treatment in a specific subset of patients.

“A group of us found that if we used this procedure for acute fractures in the first 6 weeks in people with a high level of pain, we saw dramatic results,” Dr Bird told MJA InSight in an exclusive podcast. “The need for analgesia dropped rapidly and many patients got out of hospital more quickly. So, the trials just didn’t fit with what we were seeing.”

Dr Bird said that the problem with the 2009 trials was that they were targeting the wrong people. To begin with, only a small proportion of those enrolled had acute fractures of less than 6 weeks in duration.

“What happens after 6 weeks is that the fracture begins to heal and harden, and you can’t get enough cement in to make a difference. If you get in early, you can restore some of the normal anatomy, and you avoid the muscle spasms and other associated symptoms.”

The other problem with the trials is that they enrolled patients who didn’t necessarily have high pain levels.

“If you don’t have much pain to begin with, your pain level might not go down much,” Dr Bird commented.

In designing their new trial, Dr Bird and his colleagues accounted for these perceived shortcomings, enrolling only patients with fractures with a duration of 6 weeks or less, and only those patients with high pain levels of seven or more out of 10. One-hundred and twenty patients were randomised to vertebroplasty or to a sham procedure, involving sedation and an incision, which was convincing enough that the majority of patients in the placebo arm believed they’d had the real procedure.

“There was a clear benefit of vertebroplasty over placebo. The pain scores fell at all levels from 3 days right out to 6 months. There were improvements in overall physical ability, and a reduction in the need for analgesia and hospitalisation,” Dr Bird said.

Dr Michael Johnson, an orthopaedic surgeon at Melbourne’s Epworth Healthcare, told MJA InSight that in his experience osteoporotic compression fracture was a self-limiting problem for the majority of patients.

“I’ve always had this belief that most people get better with no treatment. But I’ve used vertebroplasty occasionally and the effect can be miraculous, so I think there’s a group of people who can be helped.”

He pointed to the very elderly and the frail in particular as a group who could benefit from vertebroplasty.

“For these people, a compression fracture can change the situation from where they’re able to manage to where they can’t cope. In that group, vertebroplasty is a very good means of hastening recovery and getting them independently back in their home. This is a group that also tends to tolerate narcotic analgesics poorly. They can cause confusion and make people unsteady on their feet and at risk of another fracture, which is the last thing you want.”

He said that the removal of a Medicare item number for vertebroplasty was contrary to the clinical experience of a lot of people who had used the procedure.

“I don’t think the decision should have been based on randomised trials in its entirety. I think that there were major problems with the two trials, and I also think that randomised trials aren’t necessarily a good way of identifying subgroups which may benefit.”

Dr Johnson said that the next step should be for a working group of specialists to be set up to determine an appropriate, more restrictive descriptor for the use of the procedure, with a view to a new Medicare item number.

Dr Bird agreed, but said it was first necessary to change the perception around vertebroplasty.

“The problem is once something’s been maligned, it’s very hard to bring it back. So that’s what we’re trying to do at the moment, to undo that and show where it’s effective. We need to get the support of different societies – rheumatologists, endocrinologists, proceduralists. We’re seeing some international interest in our trial, with an editorial published in the Lancet. And slowly, slowly, the tide may turn.”

To find a doctor, or a job, to use GP Desktop and Doctors Health, book and track your CPD, and buy textbooks and guidelines, visit doctorportal.

more_vert

more_vert

Both Vertebroplasty and Kyphoplasty have well documented benefits and are routinely carried out in the United States and Europe.

As a patient who sustained compression fractures, that still cause significant pain, it was so disappointing to be disregarded by Australian doctors and surgeons. Particularly in the early stages, when intervention would have been most effective.

To later learn that the procedures were not available in the country, at all, was unbelievable. I wish I could have at least been informed of the limitations, so I could have gone overseas for treatment that, I know, would have offered better recovery outcomes.

Please restore this straight forward procedure to the public health system. I am in constant severe pain daily thus denying me the rights to a basic lifestyle.

Thank you

“A group of us found that if we used this procedure for acute fractures in the first 6 weeks in people with a high level of pain, we saw dramatic results”

“Dr Michael Johnson, an orthopaedic surgeon at Melbourne’s Epworth Healthcare, told MJA InSight that in his experience osteoporotic compression fracture was a self-limiting problem for the majority of patients.”

So … most pain from acute events re-adapts well (yes Michael, I see that too!), BUT if there is benefit from surgery that is best implemented in the first 6 weeks.

Hmmm – I still see a problem.

The problem of early unnecessary intervention for many is still there, particularly if they find themselves in a vulnerable context.

PS: Consider all of this from a pain neurobiology perspective and it starts to make sense.

There is a warning in this saga regarding the current MBS review, which is moving in the direction of greatly restricting access to Medicare-subsidized investigations and treatment on the basis of “evidence” and “guidelines”. For example, it has been proposed that patients on thyroxine replacement will only be monitored by TSH levels and will have to pay for a free T4 and/or free T3 level themselves if their treating clinician thinks it is indicated. I treat many patients with hypothyroidism and there are certainly situations where I would probably have made an incorrect decision on thyroxine dosing if I only had the patients ‘s symptoms and a TSH result to guide me. I urge all clinicians to read the many proposed changes to the Medicare item descriptors. The MBS Review appears to be an attempt to reduce Medicare funding by imposing a strict set of “evidence-based” rules on funding, regardless of how strong or weak the evidence base is, and regardless of whether it can be applied generally or only to specific sub–groups, as in the case of vertebroplasty. Regulations will replace clinical judgment and experience if the profession does not fight such proposals.

It poses the interesting conundrum for evidence based medicine believers ( I will confess to agnosticism verging on atheism): How can a procedure declared anathema ever be resurrected, given that its very performance is a rejection of the existing evidence? Clearly a brave ethics committee approved this trial, and a courageous hospital administrator allowed the funding for this old-fashioned, disproved surgery to be performed on public patients using taxpayers’ money. The lack of a Medicare number would mean a private patient would have to bear the full cost personally, akin to having cosmetic surgery.

Had the study results confirmed the accepted evidence that this procedure was ineffective, I suspect a journalistic witch hunt like the St Vincent’s chemotherapy ‘underdosing scandal’ would have ensued, ‘doctors perform unnecessary surgery, banned by Medicare, in dozens of poor public patients’ or ‘rip-off doctors charge private patients $20K+ for unnecessary surgery’.

Kudos to Drs Bird, Diamond, and Clark, who deserve at least a (Barry) Marshall Prize for bravery, even if not a Nobel.

Working as a Fellow in Hand Surgery in England in 1990, I did a general orthopaedic trauma clinic each Monday morning. I saw a young man with a Tendo Achilles rupture, discussed the straightforward repair operation with him, then brought in my lower limb counterpart to hand him over. To my surprise, the Ortho Senior Reg informed the patient and me that they did not do TA repairs in this unit, because the published evidence, especially from Sweden, was that non-operative management was as good as surgery. I left a little sheepishly, as the patient looked perplexed by the polar difference of opinions.

Over three months later I saw the same man in the acute trauma clinic. Following his 12 weeks of casting and splintage, then physio, his pseudotendon had re-ruptured. He pleaded with me to do an operation, as I had done this operation before, whereas the locals had no experience. I regretfully told him I was only allowed to operate on hands, and handed him back to my colleague who planned another above-knee cast…

The problem when EBM is applied to procedural skills like surgery or interventional radiology, is that it only takes 5 years before an entire generation of trainees has never seen (much less performed) a particular procedure. My English colleague probably did get better results with nonoperative tendon treatment, as he had never operated on any. The authors of this study did well to design the selection criteria, but actually having the legacy skills to do the procedure is frighteningly fortuitous – even simple differences like using more than double the volume of cement than the previous studies. A few more years, and the skill set would have been extinct.

Vertebroplasty has proven itself without doubt in the correct subgroup of patients here in WA. Our results for the last 5 years are soon to be published. Congratulations and Thank you to the immense efforts by the VAPOUR Trial team and for their ongoing efforts in restoring this procedure to the patients in Australia – Proceduralist