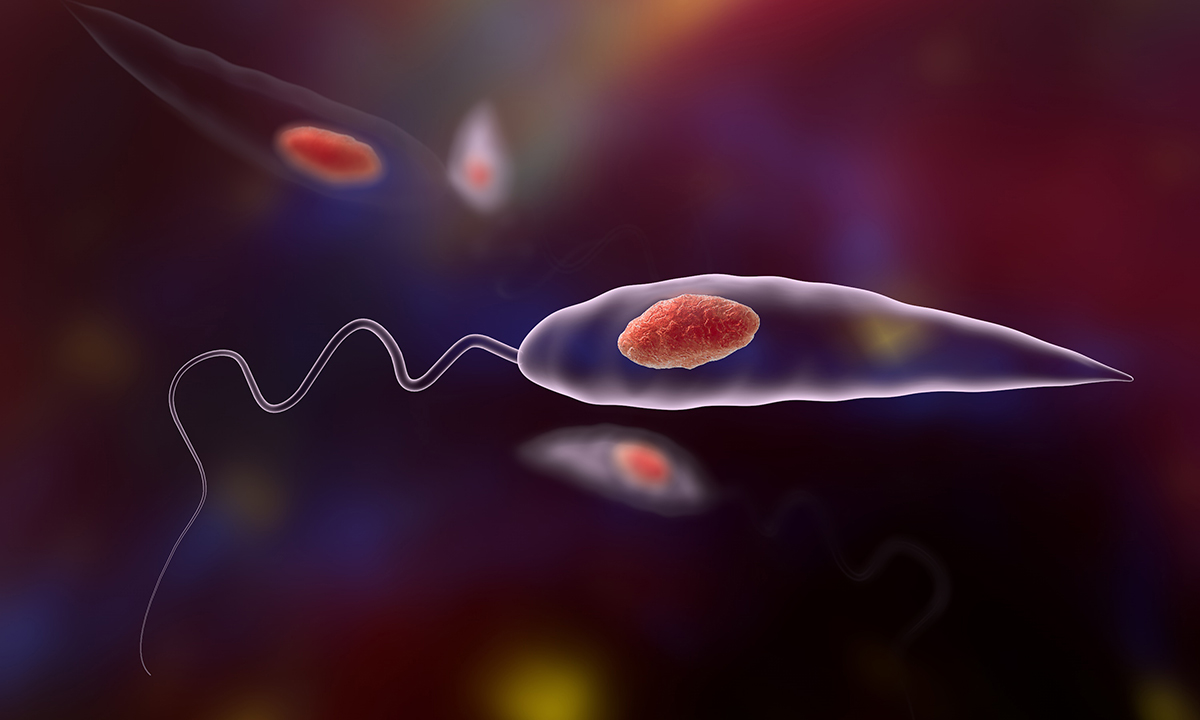

A NEWLY discovered parasite in a species of Northern Territory black fly is closely related to the flesh-eating bug Leishmania now causing catastrophic disease outbreaks among Syrian refugees in the Middle East.

Zelonia australiensis, described in the journal PLOS Neglected Tropical Diseases this month, is not thought to be pathogenic, such as several species of its relative Leishmania. However, its discovery has led to controversial warnings that Australia may not be as protected against human leishmaniasis and other tropical diseases as is widely believed.

Dr Damien Stark, study co-investigator and microbiologist at St Vincent’s Hospital in Sydney, told MJA InSight that the recent discovery highlighted how little was known about Australian parasites and their vectors.

“It was thought that there was no vector for Leishmania transmission in Australia until 2004, when Leishmania macropodium, which is transmitted through midges, was discovered in kangaroos,” he said. “Now we know that there is a vector for a similar trypanosomatid, Zelonia, as well.

“We still do not know whether Australia has a vector capable of transmitting strains of Old World and New World Leishmania that cause human disease, but given surprising recent discoveries, we would be foolish to make assumptions without further research,” he said.

“If imported Leishmania were ever to become established in domestic or wild animals in Australia, as it has in dogs overseas, this sylvatic cycle would be disastrously difficult to eradicate,” he added. “Australia is underfunding not only parasitology, but also associated medical entomology at its peril.”

Dr Stark said hospital laboratories like his own were anecdotally reporting a rise in imported cases of leishmaniasis, although, as it is not a notifiable disease, there are limited data.

However, Professor Philip Weinstein, Head of the School of Biological Sciences at the University of Adelaide, said local transmission of leishmaniasis in Australia was “almost impossible to contemplate”.

“For the disease to be transmitted locally, it requires the concurrent presence of the pathogen, a suitable vector and reservoir animals. There are no known species of human-infecting Leishmania in Australia; there are no phlebotomine sandflies of the genera that transmit the disease; and there are no known natural reservoir mammals to maintain the disease,” he said.

“It would be true that as more and more people travel, the chances of imported cases occurring are increasing,” he added. “However, because of the integrity of our medical infrastructure, cases are likely to be treated quickly and effectively as is the case, for example, with malaria.”

Dr Grant Hill-Cawthorne, Senior Lecturer in Communicable Disease Epidemiology at the University of Sydney’s Marie Bashir Institute, said the main leishmaniasis risk to Australia was from imported cases.

“If the current outbreak in Syria and the Middle East is allowed to continue, then this obviously becomes a greater risk,” he said.

Hundreds of thousands of Syrian refugees are estimated to have been infected with cutaneous leishmaniasis in camps and conflict zones of the Middle East.

Dr Hill-Cawthorne said: “Public health measures in Australia will focus on early identification of imported cases, in both humans and animals, and continuous surveillance for introduction of potential vector sandflies.”

“There were two main kinds of leishmaniasis,” he noted, “cutaneous, which was more common, and visceral, which caused systemic damage usually leading to failure of the spleen and liver and could be life-threatening.

“Cutaneous leishmaniasis should be suspected in any ulcer-like disease [occurring on exposed parts of the body] in a returning traveller from an at-risk area,” he said.

“Visceral leishmaniasis is much harder to diagnose, and usually should be on the differential diagnosis of anyone with a fever of unknown origin returning from an at-risk country.”

A typical leishmaniasis infection may begin with a cutaneous sore and progress to ulceration of the mouth, palate and nose. Some cases are accompanied by a febrile illness.

Treatment options included sodium stibogluconate and other antimonial agents, liposomal amphotericin B, for resistant cutaneous disease and visceral disease, and oral miltefosine, for visceral disease, Dr Hill-Cawthorne said.

Professor Malcolm McConville, of the Department of Biochemistry and Molecular Biology at the University of Melbourne, warned that symptoms of leishmaniasis could appear many years after initial infection.

“The prevailing view is that once infected, parasites may persist in the body for the life of the individual, in some cases, even after successful drug therapy,” he told MJA InSight.

To find a doctor, or a job, to use GP Desktop and Doctors Health, book and track your CPD, and buy textbooks and guidelines, visit doctorportal.

more_vert

more_vert

Thank you for the information. Is Miltefosine available in Australia?