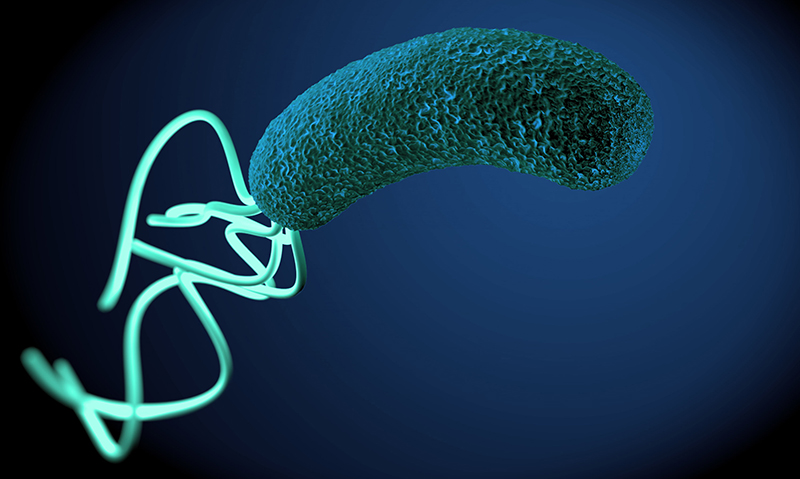

TREATMENT regimens for Helicobacter pylori infection should be both evidence-based and reflective of local antibiotic resistance patterns, according to a leading expert.

Associate professor at the department of gastroenterology in the University of Sydney, Peter Katelaris, told MJA InSight that while there is a lot of “noise in the literature” around antibiotic resistance, it was important to understand regional differences.

“In some places, clarithromycin resistance is high, especially where it has been used for a long time as monotherapy for other infections. But we’ve shown that in Australia, there are actually low rates of H. pylori resistance to clarithromycin.

“This is why it remains part of recommended first-line therapy here,” he said.

Professor Katelaris co-authored a clinical focus article, published today in the MJA, which summarised the causes, impacts and treatment of H. pylori.

H. pylori infection is a major cause of morbidity and mortality worldwide. More than 50% of the global population is estimated to be infected, the author said. The infection is the cause of peptic ulcer disease, gastric cancer and gastric mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue lymphoma, and causes symptoms in a subset of patients with functional dyspepsia.

- Related: MJA — Epidemiology, clinical impacts and current clinical management of Helicobacter pylori infection

- Related: MJA — Helicobacter pylori: what does it taste like?

The authors wrote that the most widely used and recommended therapy in Australia is a triple therapy, consisting of a proton pump inhibitor, amoxycillin and clarithromycin, usually for 1 week.

Antimicrobial resistance was a major determinant of outcome of eradication therapy, and as a result, trends in resistance must be monitored. However, individual patient susceptibility testing is usually not necessary as it rarely guides the choice of therapy.

The authors wrote that when first-line therapy fails, there are several proven second-line options available.

“In experienced centres, final eradication rates with judiciously chosen therapy should approach 99%,” they wrote.

Professor Katelaris said that while H. pylori has been an intensely researched area over the past 30 years, there was still a need for further studies.

“We need ongoing surveillance of outcomes to make sure that resistance is not increasing.”

Co-author of the paper, Professor Hazel Mitchell from the school of biotechnology and biomolecular science at the University of NSW, said that despite the high prevalence of H. pylori infection worldwide, the bacteria should never be considered commensal.

“The vast majority of individuals infected with H. pylori develop gastritis, and of these many are asymptomatic. Once acquired, H. pylori infection is lifelong unless it is treated.

“Those infected with H. pylori who are asymptomatic have the potential to develop more serious disease outcomes,” Professor Mitchell said.

Professor Barry Marshall, Nobel Laureate and founder of the Marshall Centre for Infectious Diseases Research and Training at the University of Western Australia agreed, saying that “even the most ‘non-toxic’ helicobacters always cause active gastritis”.

“Peptic ulcer and cancer risk exist for all helicobacter strains, although more so for strains carrying the cagA toxin gene.”

Professor Katelaris said that one of the complexities for the GP was the relationship between H. pylori infection and gut symptoms. Often, H. pylori infection is incidental to symptoms, and even though treating H. pylori may relieve symptoms, many patients have ongoing symptoms despite successful eradication therapy.

“However, H. pylori treatment is also a long-term risk reduction strategy, as it reduces the risk of a patient getting gastric cancer and peptic ulcer disease,” Professor Katelaris said.

Professor Marshall said that the biggest challenge facing H. pylori treatment was managing the patients who have failed therapy or who may be allergic to penicillin.

“Further treatments need to navigate away from previously used antibiotic groups and be based on sound microbiological principles. That is, confirming cure or failure after each treatment and using proven therapies rather than guesswork.

“Most treatment failures result in the emergence of a resistant clone of H. pylori afterwards. This may be because the number of gastric H. pylori is so huge and the spontaneous mutation rate is high.”

Professor Marshall added that this was why metronidazole, clarithromycin and quinolones are ineffective when used a second time. In contrast, amoxycillin, tetracyclines and bismuth could be re-used.

Professor Katelaris said that when it came to second-line therapies, substituting levofloxacin for clarithromycin is highly effective in eradicating H. pylori. However, this was limited by difficulties in accessing the medication in Australia, as it is not registered here.

“It comes down to commerce. Australia is a small market for second-line therapies.”

However, Professor Marshall highlighted that there was no universal combination regimen for all patients needing second-line therapy.

“The ‘salvage’ therapies are best left in the hands of infectious disease specialists and interested gastroenterologists,” he said.

This is due to the risk of drug side effects, issues around compliance and the need to sort out conflicting diagnostic tests.

Professor Marshall said that new technologies were offering potential alternatives to dealing with H. pylori infection.

“In the age of precision medicine, detailed genetic analysis of resistant strains obtained at gastric biopsy might be the way to go.”

more_vert

more_vert