NEW research showing “unacceptably high” rates of hepatocellular carcinoma among Indigenous Australians highlights the need for improved hepatitis B screening and follow-up, experts say.

The study of all hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) cases in the Northern Territory over the 20 years to 2010, published in the MJA, identified 145 incident cases, with an age-adjusted annual incidence of 22.7 in 100 000 Indigenous Australians, compared with four in 100,000 non-Indigenous Australians. (1)

Indigenous people aged 50‒59 years had a 0.34% individual annual risk of HCC, rising to 0.86% for 70‒79-year-olds. Crude incidence rates were steady in the first 15 years of the study period, but rose significantly in the last 5 years.

The authors wrote that there were currently “no specific recommendations to screen Indigenous Australians with HBV [hepatitis B virus] infection”.

In a more detailed retrospective cohort study of patients diagnosed with HCC in the Top End of the NT between 2000 and 2011 just 13 of the 80 new cases of HCC were detected through screening. Most people were diagnosed late, with only 28 of the 80 patients alive at 1 year after diagnosis.

The authors recommended that guidelines should explicitly support HCC surveillance in all Indigenous Australians with HBV infection from age 50 years.

They noted that HBV infection was the most common cause of HCC among Indigenous people, with 15 of the 37 Indigenous patients diagnosed with HCC in the Top End being positive for hepatitis B surface antigen (HbsAg), compared with seven of 43 non-Indigenous patients.

The study found outcomes were significantly better among HCC patients managed through a centralised multidisciplinary liver clinic at the Royal Darwin Hospital, established in 2006, compared with those managed by other medical practitioners.

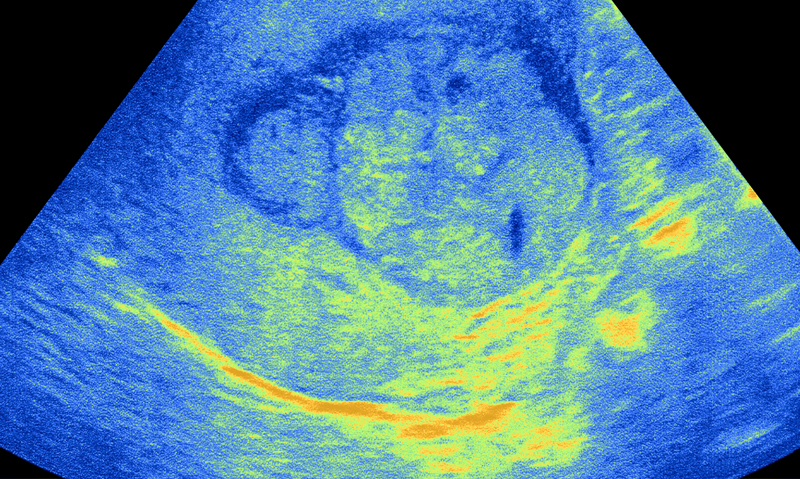

Patients attending the public liver clinic were offered 6-monthly ultrasounds scans and serum alpha-fetoprotein (AFP) tests if they had cirrhosis or if they were high risk and non-cirrhotic.

Those managed by the clinic between 2006 and 2011 had a 68% reduced risk of death compared with those managed elsewhere in the same period (17/26 v 6/30 alive at 1 year).

The authors said the difference could be partly attributable to early diagnosis, leading to less advanced disease. However, they also found patients with potentially curable disease were more likely to receive curative treatment at the liver clinic — 6/12 v 0/7 patients.

“Resources to reduce the impact of HCC should be broadly directed at HBV screening and treatment as well as HCC surveillance”, they wrote

Given that about 60% of patients in the study came from remote communities they said outreach sonography services should be developed.

To date there had not been any observable effect on HCC incidence of the universal infant HBV vaccination program introduced in 1990. However, the authors said this was not surprising, given most people diagnosed with HCC were aged over 50 years.

Associate Professor Sophia Couzos, a GP and Aboriginal health expert at Townsville’s James Cook University, agreed attention was needed to reduce the burden of HCC among Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people, suggesting that increasing awareness of existing screening and management guidelines was key.

“GPs need to be testing their Aboriginal patients for HBV status and offering the vaccine if they are non-immune”, she told MJA InSight. “Those who are chronically HBV-positive need an individualised management plan and ongoing surveillance.”

Professor Couzos referred to the National guide to a preventive health assessment in Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people, which contains advice for the prevention and early detection of HCC. (2)

The guide recommended specialist review to see if surveillance — 6‒12 monthly ultrasound and [AFP] serology — was needed in people with chronic HBV infection or chronic liver disease from other causes. It also says specialist decisions about chemoprophylaxis with antiviral drugs may be required.

Professor Geoff McCaughan, head of the liver injury and cancer group at Sydney’s Centenary Institute, said a more cost-effective surveillance option than outreach sonography as suggested in the latest study might be 6-monthly testing for serum AFP levels.

“A blood test would seem a cost-effective outreach option”, he said.

Professor McCaughan said the finding that patients in the liver clinic had better outcomes probably reflected patient selection. “The patients referred to the clinic appear to have had a higher chance of curative disease, based on the tumour characteristics.”

1. MJA 2014; 201: 470-474

2. RACGP/NACCHO 2012; National guide

(Photo: Camal, ISM/Science Photo Library)

more_vert

more_vert

This article is a timely reminder that universal HBv immunisation has nothing to do with preventing HCc for the older ATSI population and we must remember to screen and create care plans with regular AFP and USS for chronic HBV carriers. A recent Kimberley study has also identified HBV vaccine failure amongst younger Aboriginal children which createsanother dilemma.