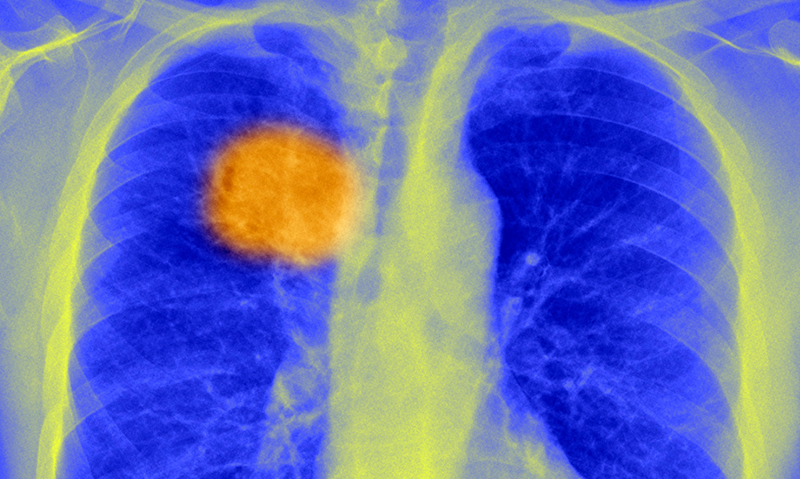

EXPERTS fear Australians are dying of lung cancers which could have been successfully removed, as new research reveals wide variation in resection rates between health districts.

The study, published in the MJA, included 3040 NSW patients diagnosed with localised (stage 1A and 1B) non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) between 2003 and 2007. It found resection was associated with a 70% reduction in deaths 5 years after diagnosis. (1)

However, a postcode lottery was apparent in the management of such patients, with one local health district performing resections in 59% of patients, compared with a state average of 38%‒43%.

The 38% rate included regions with an interstate border where patients might have not had surgery in NSW. The authors said the 43% rate was more reliable.

They concluded that deaths from all NSCLC at 5 years after diagnosis “would be reduced by about 10%” if all local health districts achieved a resection rate of 59%. Localised cases comprised 30% of all NSCLC cases of known stage in NSW.

The authors said deaths could also be prevented by increased use of lobectomies in preference to wedge resections, after finding the 5-year cumulated probability of death was 30% after wedge resection, 18% after segmental resection, 22% after lobectomy and 45% after pneumonectomy.

Associate Professor Gavin Wright, a thoracic surgeon at St Vincent’s Hospital in Melbourne and Peter MacCallum Cancer Centre, said disturbing variations in resection rates and outcomes had also been observed in Victoria. (2)

Professor Wright said that part of the problem was that surgeons not dedicated to thoracic surgery were performing the procedures.

“People get classified as having an inoperable tumour who would be operated on if an experienced thoracic surgeon was assessing them”, he told MJA InSight. “It may not even be a surgeon making the call.”

“Surgeons who aren’t thoracic experts are also more likely to do a wedge resection because it’s an easier procedure associated with lower short-term morbidity, even though the long-term outcomes are worse.”

Professor Wright said it was possible that in the latest study the correct patients were getting wedge resections, ie, those with significant comorbidities that made lobectomy unfavourable.

However, he said he was also concerned that fatalism might be a factor in treatment decisions.

“I do think there’s sometimes an attitude to ‘just do a quick wedge resection because the patient is likely to die anyway’”, he said.

“I once was asked by an intensive care specialist if the radical lobectomy I had done, with reconstruction of the patient’s airway, was a palliative procedure. I don't think they had any idea that we cure 57% of patients whose tumours we resect.”

Professor Wright said nearly all NSCLC patients at St Vincent’s Hospital now received a minimally invasive lobectomy, which had far better recovery and lower complication rates compared to other procedures, and left the patient better able to tolerate adjuvant chemotherapy.

He said patients should be referred to a specialist who was a member of a lung multidisciplinary team, or to a surgeon who was either a pure thoracic surgeon or a cardiothoracic surgeon who maintained their interest in thoracic oncology through meetings, audit, teaching and research.

Associate Professor Paul Mitchell, a medical oncologist at Melbourne’s Austin Hospital, agreed that only specialist lung cancer surgeons should make the call on whether a lung cancer patient was eligible for surgery, and which surgery was appropriate — “not an oncologist, not a radiation oncologist, not a general surgeon, not a cardiothoracic surgeon who only treats occasional lung cancer patients”.

“This has been an area plagued by nihilistic attitudes”, Professor Mitchell told MJA InSight. “That’s why it’s so important that all cases of lung cancer be discussed at multidisciplinary meetings, with a thoracic surgery expert present, at least via video- or web-conferencing.”

However, Professor Mitchell said it was hard to tell from the latest study whether the 59% resection rate in one health district was optimal, or too high.

“It would be good if the resection rates were given as a proportion of all NSCLC, rather than just localised cases, which makes it impossible to compare the results with other jurisdictions,” he said.

The Victorian research showed 19% of all NSCLC patients diagnosed in 2003 received surgery.

The authors of the current study told MJA InSight their figures could be extrapolated to show a resection rate of 16.7% as a proportion of all NSCLC cases.

Professor Mitchell said the high combined rate of wedge and segmental resections in the current study was concerning and almost certainly inappropriate.

“Although I agree that lung cancer mortality could be reduced by ensuring more patients get access to the correct surgery, I don’t think this study proves this”, he said.

1. MJA 2014; 201: 475-480

2. MJA 2013; 199: 674-679

(Photo: Michel Brauner/ISM/Science Photo Library)

more_vert

more_vert

After a general meeting of physician, surgeon, oncologist etc, it is the final decision of the thoracic surgeon that matters. Mediastinal glands and exact location in the lung are factors to be considered.