ALTHOUGH the case for provision of venous thromboembolism prophylaxis to surgical patients is reasonably “clear cut”, the case in hospitalised medical patients is less so, according to a leading Australian expert.

Professor John Fletcher, professor of surgery at the University of Sydney’s Westmead Clinical School, said improved targeting of venous thromboembolism (VTE) prophylaxis will ensure that high-risk hospital patients receive the appropriate preventive treatment and avoid its use in low-risk patients.

“The way in which we have defined medical patients who might be at high risk is probably not as precise as it needs to be”, Professor Fletcher told MJA InSight. “We need to work on how to risk-assess the medical patients to ensure that those really at high risk should receive prophylaxis. Whereas those at lower risk, you don’t want them to receive anticoagulants if it’s not strongly indicated.”

Professor Fletcher was commenting on a US study of more than 20 000 hospital patients which found the rate of 90-day hospital-associated VTE for general medical patients was low. (1)

The retrospective cohort study, published in JAMA Internal Medicine, also showed that patients who received care at hospitals with lower rates of pharmacological prophylaxis use on admission did not have higher adjusted hazards of clinical VTE compared with hospital with higher rates.

The researchers warned that quality improvement measures that indiscriminately targeted all patients with any risk factor could result in overprophylaxis and an increase in unintentional harms such as bleeding, patient discomfort and cost.

An accompanying editorial called for the development of a validated risk prediction model. “It is time to balance our goal of ensuring that every high-risk patient receives prophylaxis with ensuring that low-risk patients do not”, the editorialist said. (2)

Professor Fletcher said the editorial raised issues of relevance to Australia, adding that the duration of prophylaxis was also an important consideration for both surgical and medical patients.

“VTE occurs after hospital discharge [in about two-thirds of patients], so one of the challenges is to define patients who are not only high risk on hospital admission, but who may be at high risk after hospital discharge, so they should have prophylaxis continued out of hospital just like you do in surgical patients who have had hip replacement surgery”, he said.

Professor Fletcher said these issues would be considered in an upcoming revision of the Prevention of Venous Thromboembolism guidelines compiled by the Australia and New Zealand Working Party on the Management and Prevention of Venous Thromboembolism, of which he is a member. (3)

The NHMRC has also compiled guidelines addressing VTE prevention. (4)

Professor Ross Baker, of Murdoch University’s WA Centre for Thrombosis and Haemostasis, said the US editorial highlighted several “burning questions” regarding the provision of VTE prophylaxis to medical patients.

“What we do know is that 40% of people who suffer from venous thrombosis are medical patients who come into hospital, so it’s quite a substantial number of people who develop VTE”, Professor Baker told MJA InSight.

“It is a significant problem and the thing that we’re looking at now is how to pick those people who are at risk of venous thrombosis and give them the best treatment and then look at others who are at low risk who don’t require treatment.”

Professor Baker said the risk assessment tool used in the US study was devised in 2004 and provided scores which were not particularly useful.

He said there was general agreement that VTE prophylaxis was appropriate for people with active cancer, people with previous venous thrombosis, or people with significant inflammatory illness associated with bed rest, and this agreement provided a good start to efforts to improve identification of high-risk patients.

Dr Alasdair Millar, director of general medicine at WA’s Albany Regional Hospital, has been a long-term critic of the Australian and international VTE prevention guidelines and welcomed the US findings.

Dr Millar said under the present Australian guidelines about 80% of medical patients were eligible for pharmacological prophylaxis for a clinical condition that he estimates affects 0.3% of medical patients. He said the majority of VTE cases were asymptomatic and resolve spontaneously.

In 2012, Dr Millar and colleagues published alternative guidelines which weighted risk factors, providing pharmacological VTE prophylaxis to about 20%‒30% of medical patients assessed as being at high risk. This included patients with previous VTE or a malignancy. (5)

1. JAMA Intern Med 2014; Online 18 August

2. JAMA Intern Med 2014; Online 18 August

3. Prevention of venous thromboembolism, 4th edition

4. NICS VTE Prevention Programs in Australian hospitals

5. MJA 2012; 196: 457-461

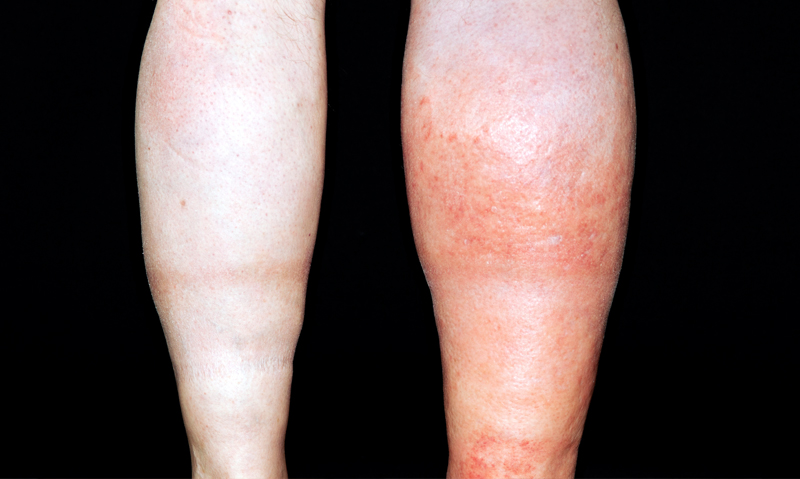

(Photo: Dr P. Marazzi / Science Photo Library)

more_vert

more_vert

The real problem is that we have not sufficiently defined the risk. Specifically, we need to define accurately who will develop VTE disease and who will succumb to its severe complications, including death.

As a respiratory physician, I deal more with established pulmonary embolism and remember well as a respiratory trainee registrar being required to admit and treat numerous completely asymptomatic patients, diagnosed with PTE on VQ scans as part of a research protocol for pre-operative assessment of orthopaedic patients awaiting knee or hip replacements. While we can discuss the limitations of VQ scan for this diagnosis… the fact remains that pulmonary embolism may never have been discovered in these patients but for their willingness to participate in research and we don’t know whether treating the PEs actually changed the course of their disease. Perhaps these were the patients destined to have “post op” PE or perhaps their own haemostatic system would have resolved the issue without intervention?

These days, the use of cardiac biomarkers (along with clinical assessment criteria), do help determine which patients are at high mortality risk and must have treatment to prevent adverse outcomes. However, in clinical practice we encounter patients with definite pulmonary embolism and coexisting bleeding problems. From these patients I’ve learnt that you “can get away with” not treating for pulmonary embolism in selected patients.

The Clinical Excellence Commission has published data that VTE is a leading cause of morbidity and mortality in Australia. More than 14,000 episodes are reported per year and 5000 deaths occur. This is more deaths than from bowel and breast cancer combined and also more deaths than from acute trauma. It is estimated that only 40% of patients admitted to hospital have an assessment for appropriate DVT prophlyaxis and only 70% of those assessed get appropriate treatment. The condition continues to be under detected and under treated. Orthopaedic surgery (particulary knee and hip surgery) entails a high risk for DVT.

VTE thrombophrophylaxis is a drug company scam. As an orthopaedic surgeon many patients will have DVT but not VTE and fatal VTE is a significant rarity in elective surgery (maybe not so in trauma).Use of chemo prophylaxis leads to wound ooze, breakdown and Joint infection that far outweighs any benefit or ability to save lives.

When we introduced prophylactic subcut. heparin for prevention of PTE at St. George Hospital, Sydney in the 1970s, it was a hard act to get our fellow surgeons in other disciplines to follow but eventually we did and much later, the physicians!. Then we found, in the era of early discharge, that we had to use such prophylaxis after the patient went home or to rehab. It is interesting to see in MJA Insight in 2014 that the discussion is still ongoing – it would be fatal to forget!