A “HUB-and-spoke” model of centralised stroke care may be key as Australia gears up to deliver better interventional stroke management, according to a leading stroke researcher.

Professor Chris Levi, director of the Hunter Medical Research Institute’s Stroke Research Group, said while there had been vast improvements in the organisation of stroke care in Australia in the past 15 years, particularly with the rollout of 85 stroke care units, a variation of the UK’s “hub-and-spoke” model may be the way of the future. (1)

Professor Levi was commenting on a BMJ analysis of the centralisation of acute stroke services in two English metropolitan areas — London and Greater Manchester. (2)

The study found a significant decline in risk-adjusted mortality at 3, 30 and 90 days after admission in London, with 168 fewer deaths at 90 days during the 21 months after services were reconfigured. In Manchester there was no impact on mortality beyond reductions in the rest of England, but both areas saw a significant decline in risk-adjusted length of hospital stay.

Professor Levi said while Australia presented different geographical challenges, local policymakers and governments should take note of the British model. He said there may be too many small stroke units in Australia’s major capital cities with a possible case to consolidate those units into three to four centres in each city.

“That would be the logical way to prepare for the endovascular revolution that I think is going to come in the next 3‒5 years”, Professor Levi said, adding that stroke care was likely to follow the lead of cardiology that had moved to interventional management in the past decade.

He said there were currently about 15 international trials investigating this intervention.

Professor Craig Anderson, head of the department of neurology at Sydney’s Royal Prince Alfred Hospital and senior director of the neurological and mental health division of the George Institute for Global Health, said the centralisation of stroke services remained controversial because it required hospital bypass.

He said there was one school of thought that it was best to get the patient to the closest hospital for rapid diagnosis, assessment and treatment, but not all facilities were well equipped and experienced in providing early treatment in acute ischaemic stroke.

“Stroke is a complex illness. There is a proven treatment … that is very time dependent and also there is a risk associated with it, so you [need clinicians] who are comfortable and experienced in giving t-PA [tissue plasminogen activator]”, he said, adding that there was general agreement that hospital bypass and centralisation of services was beneficial to patients. He said the London study demonstrated the “real-life” challenges and benefits of centralised stroke services.

“But the downside of it is that you can increase the workload at the centralised hospital”, he said.

Professor Levi agreed that workload was an issue that needed addressing. He said a major issue facing many stroke units was access block.

In other research published last week in The Lancet, a meta-analysis of individual patient data from 6756 patients comparing the clot-busting drug alteplase with placebo or open control found that irrespective of age and stroke severity, and despite a 2% increased risk of fatal intracranial haemorrhage, alteplase significantly improved the overall odds of a good outcome when given within 4.5 hours of stroke onset. (3)

The authors of an accompanying commentary said there was a “need for speed” in stroke treatment. “Time is the major modifier of the effect of treatment: faster treatment results in a much greater treatment effect”, they wrote. (4)

Professor Anderson said the analysis, which incorporated individual patient data from the third international stroke (IST-3) trial, was the “definitive statement” on the role of alteplase in stroke treatment and confirmed the “very strong” time dependent nature of the therapy. (5)

“The data is definitive and important to reinforce … the consistency of the treatment effect according to important subgroups, such as the very elderly,” he said.

Professor Levi said the study was confirmatory and, most importantly, showed that alteplase had just as much relative benefit in patients over 80 years old as in younger patients.

“Stroke is a very difficult illness and this drug is not a panacea, but it certainly is effective and the earlier you treat, the better.”

1. PLOS One 2013; Online 1 August

2. BMJ 2014; Online 5 August

3. Lancet 2014; Online 6 August

4. Lancet 2014; Online 6 August

5. IST-3

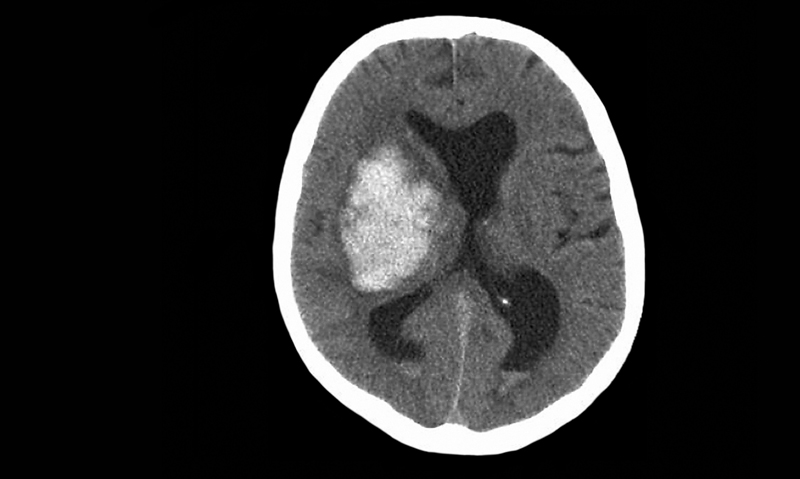

(Photo: Zephyr/Science Photo Library)

more_vert

more_vert

While care in a stroke unit, with meticulous attention to swallowing and rehab, is a safe and cost-effective way of improving outcomes for stroke, the neurologists seem to want to follow the cardiologists down the interventional line. Meanwhile, acute thrombolytic therapy for stroke carries a significant risk of death by acute haemorrhage, and we still don’t have good tools to predict which recipients will bleed.

How ironic that the story is illustrated by a CT with a huge intracerebral bleed!

The Lancet meta-analysis is hugely biased by open-label trial data from IST-3. Readers may find a detailed critique illuminating (1). Uncertainties remain (2). This is just a re-hash of old data, not new evidence. Levi trots out the "endovascular revolution… going to come in the next 3‒5 years”. Maybe. Trials of endovascular management have been hugely disappointing, with no clinical benefit despite higher vessel patency rates (3,4). Nor does an ischaemic penumbra identify those who will benefit (5). This should lead us to question the open-artery hypothesis. Maybe we will solve it, but Levi telling us what will happen does not fill me with confidence that he is applying an unbiased, cool scientific head to the problem.

Neurological emergencies need to be seen quickly to deal with immediate life-threats and differential diagnoses at the nearest ED. The failed airway management, the uncontrolled seizure, the missed snake envenoming denied early antivenom…

Should we make sure confirmed stroke patients get rapidly transferred to regional stroke units after initial stabilisation-YES. The BMJ paper provides good data to support this. Should we give TPA at regional EDs with telemedicine support- PERHAPS, although first I'd like to see a well-designed trial. But should we start to institute ambulance diversion for endovascular treatments? NO. We must do proper clinical trials first to justify the cost and make sure we aren’t doing more harm than good. Our health system is in crisis, and the last thing we need is to throw money at an approach that could be associated with marginal benefit or even harm.

1. Ann Emerg Med. 2013;61:489-98. 2. BMJ 2013;347:f5215. 3. N Engl J Med. 2013;368:904-13. 4. N Engl J Med. 2013;368:893-903. 5. N Engl J Med. 2013;368:914-23.