AUSTRALIAN experts have cautioned against the introduction of lung cancer screening of high-risk patients because of minimal cost-benefit ratios and the high rate of false-positive results.

An editorial in the latest MJA says primary prevention is far more effective than screening in lung cancer. (1)

The authors wrote that a national lung screening program was likely to strain health care expenditure, already stretched by expansions to breast and bowel screening programs.

“While systematic screening would likely save some lives, its running costs may be equivalent to the annual expenditure on all lung cancer care”, they wrote.

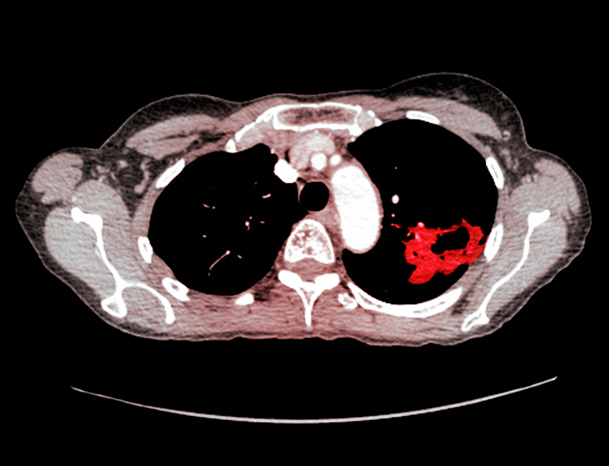

The authors referred to the recently updated US-based National Lung Screening Trial (NLST), which found that screening with low-dose computed tomography (CT) resulted in a 20% survival benefit among smokers. The NLST was a randomised trial that compared the efficacy of low-dose CT for lung-cancer screening with chest radiography in 53 454 smokers aged 55–74 years with a minimum of 30 pack-years of smoking and no more than 15 years since quitting. (2)

The MJA authors estimated the cost in Australia of saving one life through screening would be $530 487 compared with the current $250–$1000 per person spent on smoking cessation interventions, which added 4 years of life to each quitter in their early sixties.

Research published last week in the New England Journal of Medicine based on data from the NLST found that screening with low-dose CT prevented the greatest number of deaths from lung cancer among those at highest risk but prevented very few deaths among those at lowest risk. (3)

The researchers said their findings provided empirical support for risk-based targeting of smokers for such screening.

The number of participants who would need to be screened to prevent one lung cancer death decreased significantly with an increasing risk of lung cancer death (5276 in quintile 1, 531 in Q2, 415 in Q3, 171 in Q4 and 161 in Q5). The ratio of the number of participants with false-positive results to the number of CT-prevented lung-cancer deaths also decreased significantly across risk quintiles (from 1648 in Q1 vs 65 in Q5).

Professor David Barnes, a respiratory and sleep physician at the Royal Prince Alfred Medical Centre in Sydney, told MJA InSight that any lung cancer screening would have to be “handled incredibly carefully”.

“The NLST result is a best-practice scenario”, Professor Barnes cautioned. “The 20% reduction in mortality is impressive but translating that into the real world would need very clear guidelines about procedures when an abnormality is found.”

The authors of the MJA editorial made a similar assessment saying: “Lung cancer screening … appears efficacious under optimal conditions and in expert hands. The absolute benefit, however, is modest and may be rapidly eroded by small decrements in effectiveness, or minor increments in harm.”

Professor Simon Chapman, from the School of Public Health at the University of Sydney, was more scathing of the likely interpretations of the NLST results.

“The perspective provided by [the MJA editorial] should be compulsory reading for anyone tempted to now think that screening for lung cancer in smokers and ex-smokers is sensible, affordable public health policy”, he told MJA InSight.

“The estimates provided of the likely costs involved in saving a life-year should lung cancer screening gain momentum are galactic by comparison with the costs of stimulating smokers to quit.

“The case for the value of tobacco control in the [MJA editorial] is made even more compelling when we realise that lung cancer is responsible for only about 40% of tobacco-caused deaths: stopping smoking, particularly by middle age, greatly reduces early death from all diseases caused by smoking”, Professor Chapman said.

Professor Ian Olver, chief executive officer of Cancer Council Australia, said there were better, more cost-efficient ways of reducing lung cancer deaths in Australia.

“If we were really serious about reducing lung cancer, then we have a long way to go in terms of tobacco control”, Professor Olver told MJA InSight.

“The World Bank research shows that for every 10% increase in the cost of tobacco, there is a 3%–4% decrease in smoking rates. (4)

“Decreasing the availability of cigarettes — taking them out of convenience stores, service stations and newsagents, for example — would also be more cost-effective than [lung-cancer screening in a high-risk population]”, Professor Olver said.

1. MJA 2013; 199: 82-83

2. National Lung Screening Trial (NLST) Screening 2012

3. NEJM 2013; 369: 245-254

4 World Bank 2013; Tobacco Facts 1: Tobacco control in developing countries

more_vert

more_vert

The NLST study compares LD- pulmonary CT with CXR and found improvement in survival. This says nothing about the value of an annual or incident-based CXR costing about $40 in high risk individuals – as part of their smoking cessation program. Forget, the public health professor, we are doctors for real people – our patients. Remember, that only about 5 % of smokers will ever get lung cancer. And many others, lifelong non-smokers and long-ago quitters also get lung cancer. A persistent cough should always attract a CX referral. Mind you, this is just a view from general practice, not from ivory tower land where money numbers always become rubbery with many noughts added.

Joe has made a very cogent point, to which could be added, Government causing increased costs to polluters in industry and electricity production would be helpful, as both those industries add to overall health risks, cardiac, pulmonary and no doubt others that I cannot express. Such action may help industries think more pro-actively?

Excellent article and comment. I add comment to suggest another fight beyond smoking; to have local air quality measures in urban areas. As planners put more people in high-rise close to major traffic routes, until we are driving electric cars, the volatile fumes have been shown decades ago to increase the incidence of cancer, heart & vascular disease, asthma and more. Planners have no inherent connection with public health priorities to reduce health risk in living and working areas. Our population growth is occurring principally in urban areas and more trucks, buses and cars are added to the road every day in every suburb. EPAs have no capacity to undertake the testing. Environmental data on health risk is reactive and all too late.