MEASURING subjective wellbeing has become increasingly popular in social and economic studies. The Happy Planet Index, which incorporates a measure of life satisfaction, tells us that Australia is one of the world’s happiest countries, ranking in the top 10 of 143 nations.

MEASURING subjective wellbeing has become increasingly popular in social and economic studies. The Happy Planet Index, which incorporates a measure of life satisfaction, tells us that Australia is one of the world’s happiest countries, ranking in the top 10 of 143 nations.

Empirical studies have found that people who are married, healthy and active participants in society are generally happier, while people with low income, poor health, who are separated, unemployed or lacking social contact are less happy.

However, the effect of education on an individual’s level of satisfaction is not as straightforward as you might think.

Both government and individuals are investing more money into education, as it is expected that a better education will make us and our children happier through improved career opportunities, income and wealth attainment, personal relationships and health outcomes.

But higher education does not always mean higher life satisfaction, especially in developed countries, including Australia. It has been suggested that highly educated people are more likely to have higher expectations and are therefore more likely to experience greater disappointment when expectations are not met — known as relative deprivation theory.

A recent study that we conducted at the National Centre for Social and Economic Modelling (NATSEM) at the University of Canberra was based on a sample of about 9000 people drawn from the Household, Income and Labour Dynamics in Australia (HILDA) 2009 Survey. It examined the relationship between education and life satisfaction.

Preliminary results uncovered a general negative relationship between higher education and life satisfaction. However, further analyses show that this relationship does not necessarily exist for every cohort.

Younger generations (those born after 1955) are, not surprisingly, more likely to have higher education than older generations (born in or before 1955).

However, these younger generations were more likely to be less satisfied with their lives when compared with older generations.

It is unclear why younger generations are less happy than older generations, despite their higher levels of education. It may be that older Australians are more likely to possess an inherent sunnier disposition than younger generations, having lived through difficult economic and political times.

It may also be that younger Australians have more pressures placed on them, with many having to juggle work, life and family in a faster paced society.

Among older generations, those who hold a masters or doctorate were the least happy, while those with year 11 or below, a graduate certificate or diploma were the most satisfied with their life. For younger generations, those with university degrees were most satisfied, while those with year 11 or below were least happy.

These results are likely to be linked to the fact that younger generations require a higher level of education than past generations to secure a well-paid job, which leads them to feel satisfied with their lives.

However, the story is different when looking at health professionals, which includes medical practitioners and nurses, who are among the most educated group in our society, with 80% having a bachelor degree or above.

However, the story is different when looking at health professionals, which includes medical practitioners and nurses, who are among the most educated group in our society, with 80% having a bachelor degree or above.

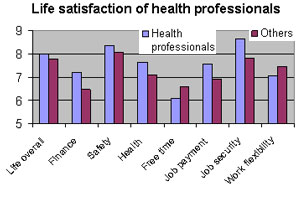

Regardless of generation, health professionals were found to be much more satisfied with their job and life, especially with their finance, health, safety, job payment and security, though not surprisingly, they were less happy with their free time and work flexibility.

The relative happiness of highly educated health professionals compared to similar groups in society is good news, but is probably not a surprising finding for MJA InSight readers. With a little attention to work–life balance, health professionals might yet be the most satisfied people in Australia.

Dr Honge (Cathy) Gong is a research fellow in the children and family team at the National Centre for Social and Economic Modelling (NATSEM) at the University of Canberra. Ms Rebecca Cassells is an acting principal research fellow at NATSEM.

Posted 29 August 2011

more_vert

more_vert

Thanks for the article, being an IMG in Australia for past 2 years has been the worst experience of my whole life, thanks for the nonsense requirements and unwarranted hassles and still can’t work…. and am happy…. yeah, right

It still could be statistically significant if the 95% CI don’t intersect… but, you’re probably right

‘health professionals were found MUCH MORE SATISFIED with their lives’?!

Looking at the graph and actual numbers the difference between 7.9 and 8.0 on the ‘NATSEM happiness scale’ would not even be statistically significant, let alone clinically.

Is this supposed to be research to be taken seriously?

It comes as no surprise that this discussion about happiness makes no mention of spirtuality, faith, altruism, or eschewing secular materialism and its empty aspirations.

“Where your treasure is, there will your heart be also” or to put it in another way, “Life is more than meat, the body more than raiment.” The more we lose, the more we gain.

Did you see this:

“With a little attention to work–life balance, health professionals might yet be the most satisfied people in Australia.” Cheers/Cats