The theme of this year’s World Health Day on April 7—Beat diabetes—adds to a 2011 UN initiative to stem the rise in prevalence of diabetes by 2025, as well as to reduce premature deaths from non-communicable diseases, part of Sustainable Development Goal 3. In today’s Lancet, the NCD Risk-Factor Collaboration (NCD-RisC) report that in 2014, an estimated 422 million people worldwide were living with diabetes—roughly a four-fold increase over the past 35 years. The NCD-RisC pooled data from 751 studies that measured either fasting plasma glucose or haemoglobin A1c to determine global and regional trends in diabetes prevalence.

Preference: World Health

1236

The world is turning to flab

Rich countries are facing an epidemic of severe obesity and around one in five worldwide will be obese by the middle of next decade unless there is a major slowdown in the rate at which people are putting on weight, according to a major international study involving data from 19 million adults across 186 countries.

Already, more than 2 per cent of men and 5 per cent of women are severely obese, and researchers have warned that the prevalence is set to increase and current treatments like statins and anti-hypertensive drugs will not be able to fully address the resulting health hazards, leaving bariatric surgery as the last line of defence.

In a result which underlines the extent of the obesity challenge, research by the NCD Risk Factor Collaboration* has found that that between 1975 and 2014, the prevalence of obesity among men more than trebled from 3.2 per cent to 10.8 per cent, while among women it surged from 6.4 to 14.9 per cent.

The study’s authors warned that on current trends, 18 per cent of men and 21 per cent of women will be obese by 2025, meaning there was “virtually zero” chance of reaching the global target of halting the prevalence of obesity at its 2010 level.

Instead, in the next nine years severe obesity will supplant underweight as a bigger public health problem, especially for women.

“The world has transitioned from an era when underweight prevalence was more than double that of obesity, to one in which more people are obese than underweight,” the study, published in The Lancet, said.

But although the world is getting fatter, it is also getting healthier, confounding concerns about the detrimental health effects of being overweight.

Writing in the same edition of The Lancet , British epidemiologist Professor George Davey Smith said that the increased in global body mass index (BMI) identified in the study had coincided with a remorseless rise in average life expectancy from 59 to 71 years.

Professor Davey Smith said this was a paradox, given the “common sense view that large increases in obesity should translate into adverse trends in health”.

Generally, a BMI greater than 25 kilograms per square metre is considered to be overweight, while that above 30 is obese and above 35, severely obese.

As the BMI increases above the “healthy” range, it is associated with a number of health consequences including increased blood pressure, higher blood cholesterol and diabetes.

The fact that increased BMI has not so far been associated with decrease longevity has led Professor Davey Smith to speculate that in wealthier countries access to cholesterol lowering drugs and other medications have dampened the adverse health effects, sustaining improvements in life expectancy despite increasing weight.

But he warned this effect would only be limited – many people would not be able to afford such treatments, and pharmacological interventions can only alleviate some of the health problems associated with being obese, meaning many health effects are likely to emerge in greater number later on as the incidence of obesity increases.

One of the most important aspects of the NCD Risk Factor Collaboration report is the insight it provides into differences in the nature and prevalence of weight problems between countries and regions.

For instance, it shows that the biggest increase in men’s BMI has occurred in high-income English-speaking countries, while for women the largest gain has been in central Latin America.

At the extreme, the greatest prevalence of overweight and obesity was in American Samoa, where the age standardised mean BMI for was 32.2, and for women, 34.8. Other areas where the mean BMI for both men and women exceeded 30 included Polynesia, Micronesia, the Caribbean, and several countries in the Middle East and north Africa, including Kuwait and Egypt.

The researchers found that male and female BMIs were correlated across countries, though women on average had a higher BMI than men in 141 countries.

But, in a sign that the rate of weight gain in a country may slow after a certain point, the researchers found that from 2000 BMI increased more slowly than the preceding 25 years in Oceania and most high income countries.

Alternatively, it sped up in countries where it had been lower. After 2000, the rate of BMI increase steepened in central and eastern Europe, east and southeast Asia, and most countries in Latin America and Caribbean.

The results suggest that public health campaigns and other polices aimed at curbing weight gain and encouraging healthier diets and more physical exercise are so far having little effect, spurring policymakers to consider different measures.

Though not canvassed in the study, one idea gaining support intnationally is for governments to impose a tax on sugary foods.

The United Kingdom will levy a tax on sugary drinks from next year, similar to one already in place in Mexico, and the World Health Organisdaiton has backed the policy as a way to curb the rapid increase in cases of diabetes in the world.

While overweight and obesity has become a major public health problem, particularly in wealthier countries, inadequate nourishment remains a health scourge in much of the world.

The NCD Risk Factor Collaboration report shows that millions continue to suffer serious health problems from being underweight, and warned that “the global focus on the obesity epidemic has largely overshadowed the persistence of underweight in some countries”.

As in other respects, global inequality in terms of weight have increased in the past 40 years, and while much of the world is getting fatter, in many areas under-nutrition remains prevalent.

The study found that more than 20 per cent of men in India, Bangladesh, Timor Leste, Afghanistan, Eritrea, and Ethiopia are underweight, as are a quarter or more of women in Bangladesh and India.

* The study drew on 1698 population-based data sources involving body mass index measurements taken from 9.9 million men and 9.3 million women in 186 countries between 1975 and 2014.

Adrian Rollins

Rich told: stop taking from the poor

Rich countries have been urged to reduce their reliance on overseas-trained doctors and improve workforce planning to help address severe shortages of medical practitioners in developing nations.

A dramatic upsurge in the number of doctors has averted fears of a world-wide doctor shortage, but the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development said large numbers were flocking to wealthy nations from Africa, exacerbating problems with access to care among the poor.

According to the OECD report Health Workforce Policies in OECD countries: Right Jobs, Right Skills, Right Places, there were 3.6 million doctors practising among its member countries in 2013, up from 2.9 million in 2000 – a 24 per cent increase in just 13 years.

Much of this increase has been driven by a sharp expansion in medical school intakes and training programs.

Australia has been part of a global trend toward boosting medical school intakes – since 2004, the number of medical school places has soared by 150 per cent to reach more than 3700, creating problems further along the training pipeline, where there has not been a commensurate increase in capacity.

But the growth in doctor numbers has also been fuelled by recruitment from overseas.

The report found that 17 per cent of all active doctors working in OECD countries came from overseas, and though a third originated in other OECD nations, “large numbers also come from lower-income countries in Africa that are already facing severe shortages”.

While the United States and the United Kingdom are the two most popular destinations for overseas-trained doctors, Australia is among the most heavily reliant on them to help plugs gaps in the medical workforce.

They comprise about a quarter of all doctors working in Australia, and make up more than 40 per cent of those practising in rural and remote regions.

The OECD said this reliance was coming at a heavy cost to poor countries that were training doctors, only to see many of them emigrate rather than ease the local shortage.

OECD Secretary-General Angel Gurria said that with the threat of a global doctor shortage averted, it was time to focus attention on improving the distribution of the medical workforce to ensure all had access to high quality care.

“The evolving health and long-term care needs of ageing populations should stimulate innovation in the health sector, where attention should focus on creating the right jobs, with the right skills, in the right places,” Mr Gurría said. “Countries need to co-operate more to ensure that the world gets the strategic investments in the health workforce that are necessary to achieve universal health coverage and high-quality care for all.”

The AMA has anticipated the OECD’s call, late last year releasing a Position Statement recommending that Australia not recruit doctors from countries which have an even greater need for them.

Australia is already a signatory to the World Health Organisation’s Global Code of Practice on International Recruitment of Health Personnel, which calls for improved workforce planning to allow nations to respond to future needs without relying “unduly” on the training efforts of other countries, particularly low-income ones.

But some researchers have argued that not only would it be unfair to constrain the ability of doctors from poorer countries to choose where they would like to practice, but such restrictions could also have the perverse effect of discouraging people in these locations from considering a career in medicine, exacerbating the shortage of medical workers.

AMA Vice President Dr Stephen Parnis said that improved workforce planning was an “urgent priority”.

The Abbott Government abolished Health Workforce Australia and absorbed its functions within the Health Department, a move Dr Parnis condemned as short-sighted.

In its final report, the HWA confirmed that Australia had sufficient medical school places, and instead urged attention on improving the capacity and distribution of the medical workforce – a task that the AMA hopes the National Medical Training Advisory Network will be able to fulfil.

A particular concern is difficulties in recruiting and retaining doctors in rural and regional areas.

The OECD has urged countries to use a mix of financial incentives, regulations and technologies such as telemedicine to help reduce regional disparities in access to care.

The Federal Government has announced the establishment of 30 regional training hubs and an expansion of the Specialist Training Program, but the AMA has voiced doubts that these initiatives on their own will be enough, and has instead called for a third of all domestic medical students to be recruited from rural areas.

The Government has so far resisted the suggestion, and Health Minister Sussan Ley told the AMA Federal Council last month that she was “not interested” in imposing regulations that would tie doctors to practice in a particular geographic area.

Adrian Rollins

E-cigs: a help or a harm?

In December, the AMA issued a Position Statement on Tobacco Smoking and E-Cigarettes in which it called for nationally consistent controls on the marketing and advertising of e-cigarettes, including a ban on sales to children. The AMA has raised concerns that e-cigarettes are appealing to young people, undermining tobacco control efforts, and says there is no evidence to support their use as an aid to quitting smoking.

Below, AMA member Dr Colin Mendelsohn, a tobacco treatment specialist, raises objections to the AMA’s current position on e-cigarettes, and the AMA responds.

Is the AMA statement on e-cigarettes consistent with evidence?

By Dr Colin Mendelsohn, tobacco treatment specialist, The Sydney Clinic*

* Dr Colin Mendelsohn has received payments for teaching, consulting and conference expenses from Pfizer Australia, GlaxoSmithKline Australia and Johnson and Johnson Pacific. He declares to have no commercial or other relationship with any tobacco or electronic cigarette companies.

The recent AMA statement on smoking takes a very negative position on electronic cigarettes (e-cigarettes). While there is still much to learn about e-cigarettes, there is growing evidence to support their effectiveness and safety for smoking cessation and harm reduction. Many experts feel that e-cigarettes are a potentially game-changing technology and could save millions of lives. 1

The AMA position statement does not reflect the current evidence in a number of areas. For example, there is currently no evidence for the AMA’s statement that ‘young people using e-cigarettes progress to tobacco smoking’ (the gateway effect). In the UK for example, regular use of e-cigarettes by children is rare and is confined almost entirely to current or past smokers. 2 Research in the US has found that increased access to e-cigarettes is associated with lower combustible cigarette use, rather than the opposite being true. 3

Understandable concerns are raised that increasing the visibility of a behaviour that resembles smoking may ‘normalise’ smoking and lead to higher rates of tobacco use. However, since e-cigarettes have been available, smoking rates have continued to fall. In the US, daily smoking by adolescents has dropped to a historic low of 3.2%. Adult smoking rates in the US and UK are also at record lows.

A recent independent review of the evidence commissioned by the UK Public Health agency, Public Health England (PHE), concluded that e-cigarettes are around 95% less harmful than smoking.4 This assessment includes an estimate for unknown long-term risks, based on the toxicological, chemical and clinical studies so far. Any risk from e-cigarettes must be compared to the risk from combustible tobacco, which is still the largest preventable cause of death and illness in Australia.

Three meta-analyses and a systematic review 5-8 suggest that e-cigarettes are effective for smoking cessation and reduction. The evidence indicates that using an e-cigarette in a quit attempt increases the probability of success on average by approximately 50% compared with using no aid or nicotine replacement therapy (NRT) purchased over-the-counter.

Most of the research to date has used now-obsolete models with low nicotine delivery. Newer devices deliver nicotine more effectively and have higher quit rates.

In the UK, e-cigarettes are now the most popular quitting method and are used in 40% of quit attempts. 9 In the UK alone there are currently over one million smokers who have quit smoking and are using e-cigarettes instead, with considerable health benefit.10 It has been estimated that each year in England many thousands of smokers quit using e-cigarettes and would not otherwise have quit if e-cigarettes had not been available. 11

Many organisations disagree with the AMA’s view that ‘currently there is no medical reason to start using an e-cigarette’. The Australian Association of Smoking Cessation Professionals, Public Health England and the UK National Centre for Smoking Cessation and Training recommend e-cigarettes as a second-line intervention for smokers who are unable or unwilling to quit smoking using approved first-line therapies. In the healthcare setting there is empirical evidence that combining e-cigarettes with counselling and other pharmacotherapies such as varenicline and NRT can improve outcomes further.12

The regulatory agency in the UK (MHRA) recently licensed an e-cigarette which will be available on the National Health Service in 2016. It can be prescribed by doctors to help smokers quit and will be provided free.

In Australia, we need to have an evidence-based debate on the potential benefits and risks of e-cigarettes. Careful, proportionate regulation of e-cigarettes could give Australian smokers access to the benefits of vaping while minimising potential risks to public health. The popularity and widespread uptake of e-cigarettes creates the potential for large-scale improvements in public health.

The AMA has made a major contribution to reducing smoking rates in the past. It is well placed to take a leadership role in this debate to ensure that the potential benefits from e-cigarettes are realised.

References

1. Hajek P. Electronic cigarettes have a potential for huge public health benefit. BMC Med. 2014;12:225

2. Bauld L, MacKintosh AM, Ford A, McNeill A. E-Cigarette Uptake Amongst UK Youth: Experimentation, but Little or No Regular Use in Nonsmokers. Nicotine Tob Res. 2016;18(1):102-3

3. Pesko MF, Hughes JM, Faisal FS. The influence of electronic cigarette age purchasing restrictions on adolescent tobacco and marijuana use. Prev Med. 2016

4. McNeill A, Brose LS, Calder R, Hitchman SC, Hajek P, McRobbie H. E-cigarettes: an evidence update. A report commissioned by Public Health England. PHE publications gateway number: 2015260 2015. Available at https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/e-cigarettes-an-evidence-update (accessed February 2016)

5. McRobbie H, Bullen C, Hartmann-Boyce J, Hajek P. Electronic cigarettes for smoking cessation and reduction. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014;12:CD010216

6. Rahman MA, Hann N, Wilson A, Mnatzaganian G, Worrall-Carter L. E-cigarettes and smoking cessation: evidence from a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One. 2015;10(3):e0122544

7. Lam C, West A. Are electronic nicotine delivery systems an effective smoking cessation tool? Can J Respir Ther. 2015;51(4):93-8

8. Khoudigian S, Devji T, Lytvyn L, Campbell K, Hopkins R, O’Reilly D. The efficacy and short-term effects of electronic cigarettes as a method for smoking cessation: a systematic review and a meta-analysis. Int J Public Health. 2016

9. West R, Brown J. Electronic cigarette use for quitting smoking in England: 2015. Public Health England., 2016. Available at http://www.smokinginengland.info/latest-statistics/ (accessed March 2016)

10. Use of electronic cigarettes (vapourisers) among adults in Great Britain. Action on Smoking and Health, UK., May 2015 Contract No.: Fact sheet 33. Available at http://ash.org.uk/information/facts-and-stats/fact-sheets (accessed June 2015)

11. West R. Estimating the population impact of e-cigarettes on smoking cessation and smoking prevalence in England. 2015 [(accessed 30 October 2015)]. Available from: http://www.smokinginengland.info/sts-documents/.

12. Hajek P, Corbin L, Ladmore D, Spearing E. Adding E-Cigarettes to Specialist Stop-Smoking Treatment: City of London Pilot Project. J Addict Res Ther. 2015;6 (3) http://dx.doi.org/10.4172/2155-6105.1000244

Clarification on the AMA’s position

The recently updated AMA Position Statement Tobacco Smoking and E-Cigarettes – 2015 states:

that the AMA has significant concerns about e-cigarettes. E-Cigarettes and the related products should only be available to those people aged 18 years and over and the marketing and advertising of e-cigarettes should be subject to the same restrictions as cigarettes. E-cigarettes must not be marketed as cessation aids, as such claims are not supported by evidence.

As noted in the background to the Position Statement, the evidence supporting the role of e-cigarettes as a cessation aids is mixed and low-level.

The stance taken by the AMA on e-cigarettes is consistent with that of the World Health Organisation, Cancer Council Australia, the National Heart Foundation, the National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC) and the Therapeutic Goods Administration (TGA) – the latter two organisations being the key decision makers on whether or not e-cigarettes have a role in smoking cessation in Australia.

It is worth noting that a number of smoking cessation aids, backed by evidence, are already available through the Pharmaceutical Benefits Scheme.

The assertion that there is no evidence that e-cigarettes are a potential gateway for young people to progress to tobacco smoking is incorrect.

The AMA’s Position Statement refers to international research [1] showing that some young people who use e-cigarettes do in fact progress to tobacco smoking. Given the risk, the AMA supports a precautionary approach for children and young people.

E-cigarettes will continue to be topical. Research is being published regularly and the AMA will continue to monitor the issue.

The AMA Position Statement, which covers a range of issues, can be viewed at: position-statement/tobacco-smoking-and-e-cigarettes-2015

[1] For example see, Primack, BA., Soneji, S., Stoolmiller, M, Fine, MJ & Sargent, D. (2015). Progression to traditional cigarette smoking after electronic cigarette use among US adolescents and young adults. JAMA Pediatr. and Bunnell RE, Agaku IT, Arrazola R, Apelberg BJ, Caraballo RS, Corey CG, Coleman B, Dube SR, King BA.(2014). Intentions to smoke cigarettes among never-smoking U.S. middle and high school electronic cigarette users, National Youth Tobacco Survey, 2011-2013. Nicotine and Tobacco Research. 2014.

English as a second language and outcomes of patients presenting with acute coronary syndromes: results from the CONCORDANCE registry

Australia is one of the most culturally and linguistically diverse nations in the world, its population of 24 million including an estimated 6 million people who were born overseas.1 Australian research has shown a higher prevalence of cardiovascular risk factors among southern European, Middle Eastern and Indian immigrants.2,3 The lack of a mutually comprehensible and usable written and spoken language is a major barrier to effective communication between health care providers and patients. This potentially affects the provision of primary and secondary disease preventive care, which, in turn, may affect patient outcomes. Immigrants from non-English-speaking backgrounds have a higher incidence of admissions for acute myocardial infarction, and remain in hospital longer than their English-speaking peers.4 Communication and language barriers have also been shown to affect the provision of quality care for South Asian immigrants.5

The Cooperative National Registry of Acute Coronary Care, Guideline Adherence and Clinical Events (CONCORDANCE) is an Australian observational registry that describes the management and outcomes of patients presenting to hospitals with acute coronary syndromes (ACS) from geographically diverse regions of Australia.6 Information about patients’ demographic characteristics, including whether the patient reported English as their second language, their presenting characteristics, past medical history, in-hospital management, and outcomes at 6 months and 2 years are collected. In our study, we examined the effect of having English as the second spoken language on the treatment and outcomes for patients presenting with an ACS.

Methods

The CONCORDANCE registry currently includes data from 41 hospitals representative of regional and acute care facilities, with a range of clinical and treatment characteristics and procedural capabilities. Enrolment processes and inclusion and exclusion criteria for the registry have been described previously.6 In brief, every month each site enrols the first ten patients who present to hospital with symptoms of an ACS together with significant electrocardiographic changes, elevated cardiac enzyme levels, or newly documented coronary heart disease.

Data collection and measures

The data collected included details about pre-hospital assessment and management, and the admission diagnosis; demographic characteristics; medical history; in-hospital investigations and management, including the timing of invasive therapy; medication dosage and timing; and in-hospital events. Clinical events are defined in the Appendix. Patients were followed up to assess quality of life measures, clinical events, and medication compliance 6 months and 2 years after discharge.

Definition of English as a second language

Demographic information collected included data pertaining to Indigenous status, country of birth, and language (English as first language [EFL] v English as second language [ESL] v unknown/undocumented). Ethnic background was classified as documented in the medical record, according to participant self-report or determined when discussing the study with the participant. The focus of our study was an analysis of demographic differences, use of evidence-based therapies, and cardiovascular outcomes, according to whether the subject reported using English as their first or second language.

Statistical analysis

Patients were dichotomised according to their English language status (ESL v EFL). Data for continuous variables were summarised as means and standard deviations (SDs), and for dichotomous variables as numbers of people and percentages.

Data were analysed in SAS 9.3 (SAS Institute). Baseline data were compared in univariate analyses (χ2 tests, t tests and Wilcoxon rank sum tests). Stepwise logistic regression was used to model the predictors associated with mortality. To account for the clustering effect of hospital as a factor, generalised estimating equation correction with an exchangeable working correlation matrix was applied. Similarly, a robust variance estimator was applied to the Cox regression analysis used to model overall mortality (from admission to 6-month follow-up). The proportional hazards assumption was visually checked by plotting the estimated survivor functions, and the ratio of hazards was found to be constant across time. Estimates of adjusted survival curves from the proportional hazard model were generated using the mean of covariates method.

The following factors were included in the Cox regression model: age, sex, diagnosis, Global Registry of Acute Coronary Events (GRACE) risk score, prior percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI), prior coronary bypass grafting (CABG), in-hospital PCI, in-hospital CABG, diabetes, prior myocardial infarction, congestive heart failure, renal failure, and prior stroke.

Candidate variables for the stepwise logistic regression models included those statistically significant at α = 0.1 in univariate comparisons. GRACE risk score was included in the model regardless of the statistical significance in the univariate comparison. Generalised linear modelling was performed using a forward selection process with entry and exclusion criteria set at α = 0.1.

Missing data

For 106 patients there was no registry information about language; these patients were excluded from the models that included language as a variable. In addition, about 2% of responses for other variables were missing; patients with missing data have been omitted from analyses where these variables were included in the model.

Ethics approval

The study protocol conforms with the ethics guidelines of the 1975 Declaration of Helsinki as reflected by a priori approval in the guidelines of the institutions’ human research ethics committees. Concord Hospital was the lead site for the New South Wales sites (approval reference, HREC 08/CRGH/180). Two authors (BD and DB) had full access to the data and assume full responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the analysis. The lead author (CJ) affirms that this article is an accurate and transparent account of the study.

Results

Enrolment in the CONCORDANCE registry commenced in February 2009. In this article we present data on the first 6304 patients enrolled at 41 sites, of whom 27.7% presented with ST elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI), 47.3% with non-STEMI (NSTEMI), and 25% with unstable angina. The data used in this analysis include patients registered to June 2014.

Nearly three-quarters of the patients (4578, or 73%) were from Australia or New Zealand; 287 were from Asia (Chinese, 37; Southern Asian, 117; other Asian, 133), 498 from the United Kingdom or North America, 578 from Europe, 45 from Africa, and 318 were categorised as “other”. A total of 418 patients (6.6%) identified themselves as Aboriginal or Torres Strait Islander.

One thousand and five patients (15.9%) reported English as their second language. These patients were younger than those in the EFL group, and the prevalence of cardiovascular risk factors was higher (Box 1). The incidence of comorbidities was also higher in the ESL group, but there were no significant differences between the ESL and EFL groups in median GRACE risk score. ESL patients were more likely to be admitted to a metropolitan than to a rural hospital (70.4% v 61.1%; P < 0.001), but there were no differences in median symptom onset to admission time (2.4 h v 2.6 h; P = 0.44), median door-to-needle time (47 min v 42 min; P = 0.59), or median door-to-balloon time (118 min v 113 min; P = 0.40).

Rates of coronary angiography and PCI were lower in the ESL group, while rates of CABG were similar. ESL patients were also less likely to be referred for outpatient cardiac rehabilitation (Box 2).

The median length of hospital stay was greater for ESL patients (5 days v 4 days; P < 0.001). Antiplatelet agents such as ticagrelor and prasugrel were used less by ESL patients, but the use of other evidence-based therapies was similar in both groups (Box 3).

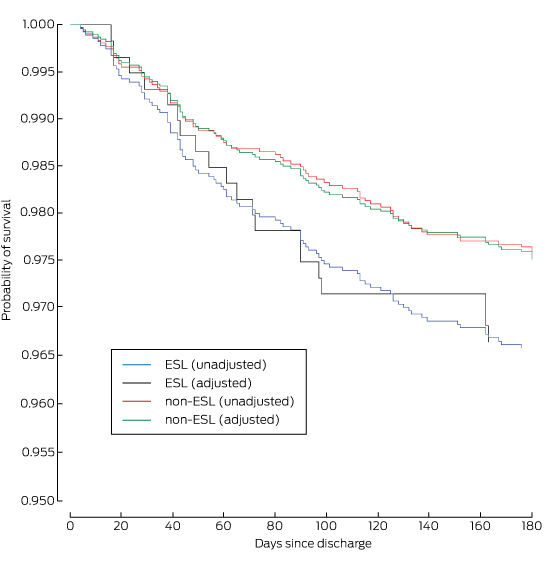

There was a higher incidence of heart failure, renal failure, stroke, recurrent myocardial infarction, major bleeding, and in-hospital mortality in the ESL group (Box 4). Independent predictors of in-hospital mortality included presentation in cardiogenic shock, cardiac arrest in hospital, in-hospital renal or cardiac failure, and having English as a second language (Box 5). At the 6-month follow-up, all-cause mortality was also higher in the ESL group (13.8% v 8.3%; P = 0.0001) (Box 6). ESL, age, in-hospital renal failure, and recurrent ischaemia were independent predictors of 6-month mortality (Box 7). The Cox regression model of survival at 6 months is outlined in Box 8.

Discussion

We found that mortality among patients presenting with an ACS who report English as their second language was higher than among those who report English as their first language. Other studies of Australian populations have not reported such a difference,7,8 but analyses of administrative data have compared populations according to standardised mortality rates, and did not specifically assess language as a marker of risk.

The incidence of diabetes mellitus, hypertension, dyslipidaemia and smoking was higher in our ESL group than among than those who used English as their first language. A systematic review2 found a higher incidence of smoking among male immigrants from the Middle East, the UK and Ireland, western and southern Europe, China, and Vietnam than among Australians of the same age. Another UK study suggested that people of South Asian origin had a higher incidence of diabetes mellitus, hypertension, dyslipidaemia and obesity than comparable Europeans,9 although the authors concluded that the measured metabolic risk factors did not entirely explain the overall differences in the incidence of coronary heart disease. Similarly, a study of Asian Indians living in Australia found a higher incidence of hypertension, diabetes mellitus and obesity than the national average.3 The proportion of patients from South Asia in our study was less than 2%, too small for us to identify this particular group as being at increased risk.

Several American studies have found longer delays to treatment for myocardial infarction for Hispanics than for non-Hispanic whites.10–12 The median door-to-needle and door-to-balloon times were slightly longer for our ESL patients, but the differences were not statistically significant.

Although patients with ESL were more likely to be admitted to a metropolitan rather than a rural hospital, we identified a reduced rate of cardiac catheterisation in ESL patients presenting with an ACS and a much lower rate of PCI than for those with English as their first language. Similar findings have been reported for Hispanic migrants in the United States13 and migrants of South Asian background in the UK.14 This is thought to reflect not a physician bias in recommending patients for revascularisation,14 but rather patient treatment preferences15 and perhaps their lack of language skills.16,17 We did not collect data on why revascularisation was not performed, but ESL patients may have had more diffuse disease, not amenable to revascularisation. Lack of English comprehension can affect access to health education that promotes health maintenance (primary prevention), which may mean patients present later, at a more advanced stage of disease.18

An Australian study4 that examined hospital discharge data for the period between 1993–94 and 1997–98 compared outcomes using an English-speaking background (ESB) v non-English-speaking background (NESB) dichotomy, based on the patient’s country of birth rather than their actual capacity to speak English. It was found that NESB patients were more likely to be admitted for acute myocardial infarction than ESB patients, possibly because of a delay in diagnosis. This study found a longer average length of hospital stay for NESB than for ESB patients, which the authors attributed to complications associated with later presentation. We also found a slightly longer length of stay in our ESL group; this may reflect differences in hospital events, but may also reflect delays in organising professional interpreters for obtaining an accurate history and facilitating informed consent for procedures.

Deficiencies in intercultural communication may play a role in the adverse outcomes for patients from culturally and linguistically diverse backgrounds.19,20 A review of the literature on cultural differences in communication suggested that doctors behave less effectively when interacting with patients from ethnic minorities, and patients themselves are also less verbally expressive and seem to be less assertive and effective during medical encounters.4

Fewer patients in our ESL group were referred for cardiac rehabilitation after discharge than patients with English as their first language. Two systematic reviews of secondary prevention programs of randomised controlled trials have shown that either supervised exercise alone21,22 or risk factor education or counselling without an exercise component22 reduced mortality. It is therefore possible that reduced attendance at cardiac rehabilitation in the ESL group also contributed to poorer outcomes. Hospitals should extend the reach of cardiac rehabilitation services by offering multilingual opportunities for patients of different backgrounds.

Second-line antiplatelet agents, such as ticagrelor and prasugrel, were used less in our ESL group. This may be partially explained by fewer PCIs in this cohort and a higher incidence of major bleeding, but clinicians may also have been concerned that they could not accurately exclude contraindications of their use in ESL patients. Prasugrel23 and ticagrelor24 reduce major adverse ischaemic events in patients presenting with an ACS more effectively than clopidogrel, and the less frequent use of these agents in our ESL patients may have contributed to their poorer outcomes.

Limitations

The patients themselves identified whether English was their first or second language, and we have no data on their fluency or length of time in Australia, and this may affect patient care and understanding. Further, we did not collect data on the use of interpreters with our ESL patients. A professionally trained medical interpreter can provide a higher degree of accuracy and confidentiality than family members or bilingual staff members; using non-professional interpreters can be expedient, but has the disadvantage of loss of productivity and additional stress on the staff involved, together with the risk of inadequate or incomplete translation. It is therefore unknown whether the use of interpreter services was adequate, and whether improving their availability would enhance clinical outcomes.

While we attempted to adjust for baseline differences, there may have been unmeasured variables, such as socio-economic status and educational level, that may have confounded the impact of English proficiency on outcomes. Finally, we did not rigorously collect data on compliance with medications and physician follow-up, which may also have affected long term outcomes.25

Conclusion

In this large registry study of patients presenting with an ACS, in-hospital and 6-month mortality was greater for patients who reported English as their second language. While this may be explained by a higher prevalence of cardiovascular risk factors leading to more advanced disease, problems of culturally specific communication may also play important roles, and should be the subject of further research.

Box 1 –

Baseline demographics of the 6304 patients at 41 sites enrolled in the CONCORDANCE database

|

|

English as second language |

English as first language |

Difference (95% CI) |

P |

|||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||

|

Number |

1005 |

5299 |

|

|

|||||||||||

|

Age [SD], years |

63.3 [14.9] |

65.3 [13.5] |

–2.06 (–3.05 to –1.07) |

< 0.001 |

|||||||||||

|

Sex (men) |

691 (68.8%) |

3699 (69.8%) |

–1% (–4% to 2%) |

0.507 |

|||||||||||

|

Diabetes |

403 (40.1%) |

1351 (25.5%) |

15% (11% to 18%) |

< 0.001 |

|||||||||||

|

Hypertension |

669 (66.6%) |

3287 (62.0%) |

5% (1% to 8%) |

0.005 |

|||||||||||

|

Dyslipidaemia |

628 (62.5%) |

2970 (56.0%) |

6% (3% to 10%) |

< 0.001 |

|||||||||||

|

Current smoker |

310 (30.8%) |

1429 (27.0%) |

4% (1% to 7%) |

0.011 |

|||||||||||

|

Median GRACE risk score [IQR] |

124 [100.8–147.6] |

125 [104.0–147.6] |

–1.00 (–3.30 to 1.30) |

0.400 |

|||||||||||

|

Prior cerebrovascular accident |

73 (7.3%) |

430 (8.1%) |

–1% (–3% to 1%) |

0.396 |

|||||||||||

|

Prior myocardial infarction |

368 (36.6%) |

1609 (30.4%) |

6% (3% to 10%) |

< 0.001 |

|||||||||||

|

Prior heart failure |

134 (13.3%) |

488 (9.2%) |

4% (2% to 6%) |

< 0.001 |

|||||||||||

|

Prior coronary artery bypass grafting |

131 (13.0%) |

681 (12.9%) |

0% (–2% to 3%) |

0.840 |

|||||||||||

|

Prior percutaneous coronary intervention |

201 (20.0%) |

1125 (21.2%) |

–1% (–4% to 1%) |

0.380 |

|||||||||||

|

Chronic renal failure |

185 (18.4%) |

411 (7.8%) |

11% (8% to 13%) |

< 0.001 |

|||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||

|

GRACE = Global Registry of Acute Coronary Events. |

|||||||||||||||

Box 2 –

In-hospital interventions in 6304 patients at 41 sites enrolled in the CONCORDANCE database

|

|

English as second language |

English as first language |

Difference (95% CI) |

P |

|||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||

|

Number |

1005 |

5299 |

|

|

|||||||||||

|

Cardiac catheter |

714 (71.0%) |

4003 (75.5%) |

–5% (–8% to –2%) |

0.002 |

|||||||||||

|

Percutaneous coronary intervention |

346 (34.4%) |

2240 (42.3%) |

–8% (–11% to –5%) |

< 0.001 |

|||||||||||

|

Coronary artery bypass grafting |

89 (8.9%) |

411 (7.8%) |

1% (–1% to 3%) |

0.234 |

|||||||||||

|

Rehabilitation referral |

495 (49.3%) |

3120 (58.9%) |

–9% (–13% to –6%) |

< 0.001 |

|||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||

Box 3 –

Discharge medications for 6304 patients at 41 sites enrolled in the CONCORDANCE database

|

|

English as second language |

English as first language |

Difference (95% CI) |

P |

|||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||

|

Number |

1005 |

5299 |

|

|

|||||||||||

|

Aspirin |

790 (85.9%) |

4276 (85.0%) |

1% (–2% to 3%) |

0.917 |

|||||||||||

|

Clopidogrel |

497 (54.0%) |

2596 (51.6%) |

2% (–1% to 6%) |

0.341 |

|||||||||||

|

Ticagrelor or prasugrel |

79 (8.6%) |

627 (12.5%) |

–4% (–6% to –2%) |

< 0.001 |

|||||||||||

|

β-Blockers |

719 (78.1%) |

3881 (77.1%) |

1% (–2% to 4%) |

0.733 |

|||||||||||

|

Angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor or angiotensin receptor blocker |

704 (76.5%) |

3799 (75.5%) |

–1% (–4% to 2%) |

0.740 |

|||||||||||

|

Statin |

815 (88.6%) |

4508 (89.6%) |

–1% (–3% to 1%) |

0.548 |

|||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||

Box 4 –

In-hospital events for 6304 patients at 41 sites enrolled in the CONCORDANCE database

|

|

English as second language |

English as first language |

Difference (95% CI) |

P |

|||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||

|

Number |

1005 |

5299 |

|

|

|||||||||||

|

Left ventricular failure |

153 (15.2%) |

444 (8.4%) |

7% (5% to 9%) |

< 0.001 |

|||||||||||

|

Renal failure |

103 (10.2%) |

268 (5.1%) |

5% (3% to 7%) |

< 0.001 |

|||||||||||

|

Myocardial infarction |

41 (4.1%) |

144 (2.7%) |

1% (0 to 3%) |

0.021 |

|||||||||||

|

Stroke |

12 (1.2%) |

25 (0.5%) |

1% (0 to 1%) |

0.007 |

|||||||||||

|

Major bleed |

106 (10.5%) |

441 (8.3%) |

2% (0 to 4%) |

0.020 |

|||||||||||

|

Death |

71 (7.1%) |

200 (3.8%) |

3% (2% to 5%) |

< 0.001 |

|||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||

Box 5 –

Logistic regression analysis of in-hospital mortality

|

Characteristic |

Odds ratio |

95% CI |

P |

||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||

|

English as first language |

0.56 |

0.33–0.94 |

0.029 |

||||||||||||

|

Cardiac arrest in hospital |

16.95 |

10.53–27.78 |

< 0.001 |

||||||||||||

|

Cardiogenic shock |

7.04 |

4.46–11.11 |

< 0.001 |

||||||||||||

|

GRACE score |

1.04 |

1.03–1.05 |

< 0.001 |

||||||||||||

|

Renal failure |

5.08 |

3.29–7.81 |

< 0.001 |

||||||||||||

|

Congestive failure |

2.08 |

1.26–3.44 |

0.005 |

||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||

|

GRACE = Global Registry of Acute Coronary Events. |

|||||||||||||||

Box 6 –

Kaplan–Meier estimates of survival at 6 months for 6304 patients at 41 sites enrolled in the CONCORDANCE database*

ESL = English spoken as second language. * Adjusted for age, diagnosis, sex, previous stroke, chronic renal failure, chronic heart failure, diabetes, prior myocardial infarction, prior coronary artery bypass grafting and prior percutaneous coronary intervention.

Box 7 –

Logistic regression analysis of mortality to 6 months after discharge for 6304 patients at 41 sites enrolled in the CONCORDANCE database

|

Characteristic |

Odds ratio |

95% CI |

P |

||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||

|

English as first language |

0.55 |

0.31–0.97 |

0.040 |

||||||||||||

|

Age |

1.09 |

1.07–1.11 |

< 0.001 |

||||||||||||

|

Renal failure |

4.67 |

2.88–7.58 |

< 0.001 |

||||||||||||

|

Ischaemia |

2.54 |

1.54–4.22 |

< 0.001 |

||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||

Box 8 –

Cox regression model of survival at 6 months for 6304 patients at 41 sites enrolled in the CONCORDANCE database

|

Characteristic |

Hazard ratio |

95% CI |

P |

||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||

|

Age |

1.08 |

1.06–1.10 |

< 0.001 |

||||||||||||

|

Diagnosis |

3.96 |

3.22–4.70 |

< 0.001 |

||||||||||||

|

Sex |

0.86 |

0.42–1.30 |

0.502 |

||||||||||||

|

Prior stroke/transient ischaemic attack |

0.95 |

0.35–1.55 |

0.868 |

||||||||||||

|

Chronic renal failure |

0.43 |

0.05–0.90 |

< 0.001 |

||||||||||||

|

Congestive heart failure |

0.36 |

0.12–0.84 |

< 0.001 |

||||||||||||

|

Diabetes |

0.90 |

0.46–1.34 |

0.642 |

||||||||||||

|

Prior myocardial infarction |

0.84 |

0.36–1.33 |

0.489 |

||||||||||||

|

Prior coronary artery bypass grafting |

1.03 |

0.52–1.53 |

0.922 |

||||||||||||

|

Prior percutaneous coronary intervention |

1.08 |

0.57–1.59 |

0.764 |

||||||||||||

|

Percutaneous coronary intervention |

1.36 |

0.85–1.87 |

0.239 |

||||||||||||

|

Coronary artery bypass grafting |

8.00 |

6.01–9.98 |

0.040 |

||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||

[Correspondence] Tuberculosis control

The Lancet Series How to eliminate tuberculosis1 rightly acknowledges that the present situation is untenable. The Series complements the Global Plan to End TB, 2016–2020,2 released by the Stop TB Partnership on Nov 20, 2015. The Global Plan to End TB, 2016–2020 is designed to accelerate progress necessary to fulfil the WHO End TB Strategy,3 which the World Health Assembly endorsed in 2014 and which aims to end the epidemic of tuberculosis by 2035.

[Comment] A breakthrough urine-based diagnostic test for HIV-associated tuberculosis

At the 44th World Health Assembly in 1991, the burgeoning, and now modern day, tuberculosis pandemic was brought to the world’s attention,1 reporting that 6 million new tuberculosis cases and 3 million associated deaths were occurring worldwide each year. The global HIV pandemic was recognised as a key factor fuelling the deterioration in tuberculosis control, and such were the grim portents of the emerging tuberculosis and HIV co-epidemic in sub-Saharan Africa that, in 1991, three London academics posed the pointed question, “Is Africa lost?”2 Now, almost a quarter of a century after tuberculosis was declared “a global emergency”, roughly 9·6 million new cases of tuberculosis and 1·5 million deaths (0·4 million deaths in HIV-positive individuals) still occur annually.

News briefs

New evidence suggests Zika virus can cross placental barrier

Zika virus has been detected in the amniotic fluid of two pregnant women whose fetuses had been diagnosed with microcephaly, according to a study published in The Lancet Infectious Diseases last month. The report suggests that Zika virus can cross the placental barrier, but does not prove that the virus causes microcephaly. “The number of reported cases of newborn babies with microcephaly in Brazil in 2015 has increased 20-fold compared with previous years. At the same time, Brazil has reported a high number of Zika virus infections, leading to speculation that the two may be linked. The two women presented with symptoms of Zika infection including fever, muscle pain and a rash during their first trimester. Ultrasounds taken at approximately 22 weeks of pregnancy confirmed the fetuses had microcephaly. Samples of amniotic fluid were taken at 28 weeks and analysed for potential infections. Both patients tested negative for dengue virus, chikungunya virus and other infections such as HIV, syphilis and herpes. Although the two women’s blood and urine samples tested negative for Zika virus, their amniotic fluid tested positive for Zika virus genome and Zika antibodies.”

Eighth retraction for former Baker IDI researcher

Anna Ahimastos, a former heart researcher with Baker IDI Heart and Diabetes Institute in Melbourne, has recorded her eighth retraction after faking patient records. “The [Baker IDI] investigation found fabricated patients records in some papers; in other papers, such as the newly retracted 2010 study in Atherosclerosis, the original data source could not be verified,” Retraction Watch reports. “The latest retraction — A role for plasma transforming growth factor-β and matrix metalloproteinases in aortic aneurysm surveillance in Marfan syndrome? — followed up on a previous clinical trial, examining how a blood pressure drug might help patients with a life-threatening genetic disorder. That previous trial — which also included 17 patients with Marfan syndrome treated with either placebo or perindopril — has been retracted from JAMA; the New England Journal of Medicine has also retracted a related letter.” A spokesperson for Baker IDI was quoted as saying: “In total, this brings the number of retractions arising from our investigations to eight and concludes the process of correcting the public record in relation to three studies with which the researcher was associated. We are not aware of Miss Ahimastos’ current whereabouts.”

Is dementia in decline? NEJM urges caution

A perspective published in the New England Journal of Medicine (doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1514434) warns that research in the same issue showing a 20% decrease in dementia incidence each decade from 1975 to the present should cause physicians and researchers to “think carefully”. “Faced with choices between equally defensible epidemiologic projections, physicians and researchers must think carefully about what stories they emphasise to patients and policymakers. The implications, especially for investment in long-term care facilities, are enormous. Our explanations of decline are equally important, since they guide investments in behavior change, medications, and other treatments. Optimism about dementia is more justified than ever before. Even if death and taxes remain inevitable, cancer, coronary artery disease (CAD), and dementia may not. But cautious optimism should not become complacency. If we can elucidate the changes that have contributed to these improvements, perhaps we can extend them. Today, the dramatic reductions in CAD-related mortality are under threat. The incipient improvements in dementia are presumably even more fragile. The burden of disease, ever malleable, can easily relapse.”

WHO releases “R&D Blueprint” in search for Zika vaccine

The World Health Organization (WHO) has set in motion a “rapid R&D response” to the Zika virus outbreak in Brazil, learning from its Ebola virus experience in West Africa. Writing on WHO’s website, Dr Marie-Paule Kieny, Assistant Director-General, Health Systems and Innovation, said “our relatively poor knowledge of the Zika virus presents a series of challenges for research and development”. “Numerous groups are looking at the feasibility of initiating animal or human testing, particularly for vaccines and diagnostics. For vaccines, the landscape is evolving swiftly, and numbers change daily. About 15 companies and research groups have been identified so far. Two vaccine candidates seem to be at a more advanced stage: a DNA vaccine from the US and an inactivated product from India. Although the landscape is encouraging, it will be at least 18 months before vaccines could be tested in large-scale trials. For diagnostics, 10 biotech companies have been identified so far that can provide nucleic acid or serological tests. Ebola taught the global R&D community many valuable lessons, and proved that when we work together, we can develop new medical products much faster than we thought possible. Although we know even less about Zika than we did about Ebola, we are learning more every day and are much better prepared to advance much-needed research to blunt the threat of Zika.”

‘Beer goggles’ a myth, says new research

Researchers from the University of Bristol in the UK have found that there is no association between the amount of alcohol consumed and perception of attractiveness, according to their study published in Alcohol and Alcoholism. The authors ran an “observational study conducted simultaneously across three public houses in Bristol”. “Excessive alcohol consumption is linked to unsafe sexual behaviours. This relationship may, at least in part, be mediated by increased perceived attractiveness of others after alcohol consumption, a relationship colloquially termed the ‘beer-goggles effect’,” the authors wrote. “Participants were required to rate the attractiveness of male and female face stimuli and landscape stimuli administered via an Android tablet computer application, after which their expired breath alcohol concentration was measured. Linear regression revealed no clear evidence for relationships between alcohol consumption and either overall perception of attractiveness for stimuli, for faces specifically, or for opposite-sex faces. The naturalistic research methodology was feasible, with high levels of participant engagement and enjoyment.”

[Correspondence] The Harvard-LSHTM panel on the global response to Ebola report

“Everyone thinks of changing the world, but no one thinks of changing himself.”1 Tolstoy’s sage words ring true when considering the huge expectations placed on many developing countries to deliver a more secure planet; however, this goal is unachievable without the necessary investment needed from their wealthy World Health Assembly colleagues.

Films the next tobacco frontier

The World Health Organisation has called for a ratings system for films that show people smoking amid warnings that screen portrayals are luring millions of young people into the deadly habit.

While a major review has found evidence that smoking bans have delivered significant health benefits for non-smokers, the WHO is urging governments to do more to deter adolescents from trying tobacco.

Though the WHO Framework Convention on Tobacco Control, which came into effect in 2005, binds signatories to ban tobacco advertising, promotion and sponsorship, The Lancet said earlier this month that that films and television shows remain a potent way circumventing such restrictions by exposing young people to images of smoking.

Hollywood is yet to kick the tobacco habit – 44 per cent of all films it made in 2014 portrayed smoking, including 36 per cent of films rated suitable for young people.

The Lancet cited calculations by the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention that seeing on-screen smoking would encourage more than 6 million youngsters to take up the habit in 2014 alone.

Though smoking rates among young people in Australia are low by international standards – just 3 per cent of 12- to 15-year-olds smoke, rising to 10 per cent of 16- to 17-year-olds – the WHO’s call is seen as a way to further undermine the appeal of tobacco among young people, which was a major goal of the country’s world-leading plain package legislation.

This comes against the backdrop of the rise of e-cigarettes and concerns they provide a pathway to smoking for young people.

A US study of young people who had never smoked traditional cigarettes found that almost 70 per cent who used e-cigarettes progressed to traditional smokes, compared with 19 per cent of those who had not.

Of some comfort in this regard are figures showing sales growth of e-cigarettes is slowing.

After expanding at a triple-digit pace in the past five years, sales growth in the US is expected to slow to 57 per cent this year and 34 per cent in 2017.

The latest evidence for the success of tobacco control measures has come from a group of Irish researchers who investigated the effect of smoking bans on health.

The study, published by the Cochrane Library, identified 33 observational studies showing evidence of a significant reduction in heart disease following the introduction of smoke-free workplaces and other public spaces.

The researchers found the greatest reduction in admissions for heart disease following the introduction of smoking bans was for non-smokers.

Adrian Rollins

more_vert

more_vert