Breastfeeding is beneficial for infants and their mothers. It protects against diarrhoea, respiratory tract and other infant infections, atopic dermatitis, asthma, obesity, diabetes and cancer.1,2 Although exclusive breastfeeding achieves optimal infant growth and development, the World Health Organization recognises that providing some breast milk to the infant is better than none.3 For mothers, breastfeeding has a contraceptive effect, and reduces the risk of type 2 diabetes, breast cancer and ovarian cancer.1

Cosmetic breast augmentation is the most common plastic surgical procedure, and its use is rising dramatically. In Australia, this surgery increased by 150% between 2001 and 2011.4 In the United States, the estimated increase for this period was 45%, although this followed a 550% increase from 1992 to 2000.5 In the United Kingdom, rates increased by 200% from 2005 to 2013.6 In this article, cosmetic breast augmentation (or breast implants) refers to procedures that change the size, shape and texture of healthy breasts. This is distinct from reconstructive breast augmentation, such as following mastectomy.

Although most cosmetic breast surgery occurs among women of reproductive age, there has been little research into pregnancy outcomes, including breastfeeding. A systematic review of breastfeeding outcomes associated with cosmetic breast augmentation surgery identified only three small, observational studies.7 One study reported reduced rates of any breastfeeding among women with breast augmentation, while meta-analysis of all three studies suggested a reduced likelihood of exclusive breastfeeding (pooled rate ratio, 0.60; 95% CI, 0.40–0.90).7 The authors recommended that studies using larger cohorts and more representative study populations be used to explore the observed association.

To test the null hypothesis that augmentation has no effect on breast milk feeding, we conducted a population-based study to determine the effect of cosmetic breast augmentation: (i) on any breast milk feeding in a subsequent pregnancy; and (ii) on exclusive breast milk feeding among women who breast milk fed.

Methods

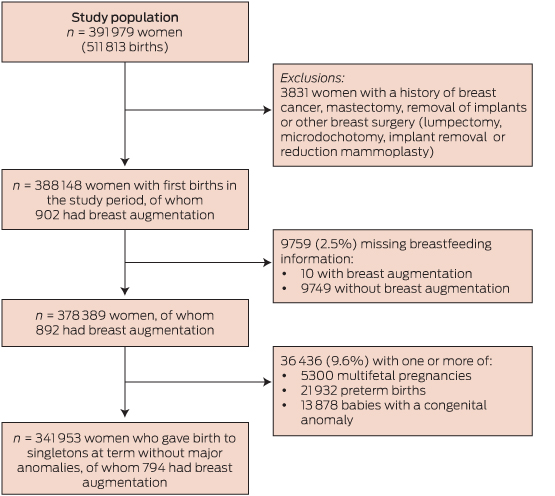

The study population was derived from the 391 979 women who gave birth in New South Wales from 1 January 2006 to 31 December 2011 (Box 1). As our intention was to examine the effect of cosmetic breast augmentation, women with breast cancer, mastectomy, breast reconstruction or other breast surgery before giving birth were excluded (n = 3831; Box 1 and Appendix 1). The remaining 388 148 women had 506 942 births. The first birth in the study period or the first birth after breast augmentation surgery was used in the primary analysis.

Data for the study were obtained from two linked population health datasets: the NSW Perinatal Data Collection (PDC; referred to as birth records) and the NSW Admitted Patient Data Collection (APDC; referred to as hospital records). The PDC is a statutory surveillance system of all births in NSW of at least 20 weeks’ gestation or at least 400 g birthweight. Information on maternal characteristics, pregnancy, labour, delivery, and infant outcomes are recorded by the attending midwife or doctor. The APDC is a census of all NSW inpatient hospital discharges from both public and private hospitals, and day procedure units, and includes demographic and episode-related data. Diagnoses and procedures are coded for each admission from the medical records according to the International Classification of Diseases, 10th revision, Australian modification (ICD-10-AM) and the Australian Classification of Health Interventions.8

Hospital records for individual women were linked cross-sectionally to birth records from 2006 to 2011 and longitudinally (from July 2000 to December 2011). Thus, the minimum lookback period for prior breast surgery ranged from 5.5 to 11.5 years. Record linkage was undertaken by the NSW Centre for Health Record Linkage (CHeReL). For this study, the CHeReL reported the quality of the record linkage9 as 3/1000 false-positive links. We were provided with anonymised data. Ethics approval for the study was obtained from the NSW Population and Health Services Research Ethics Committee.

Breastfeeding information at discharge has been collected in birth records since 2006. One or more of the following three options can be reported in tick-boxes: “breastfeeding”, “expressed breast milk” or “infant formula”.

The primary outcome was any breast milk feeding (any breast milk, with or without infant formula) at discharge from birth care. Consistent with other studies,7 the secondary outcome was exclusive breast milk feeding (only breast milk, either directly from the breast and/or as expressed breast milk) among those with any breast milk feeding.

The exposure of interest was cosmetic breast augmentation, which has a specific surgical procedure code (45528-00) in the Australian Classification of Health Interventions.4,8 This code is distinct from unilateral breast augmentation and breast augmentation following mastectomy. Hospital records from 2000 onwards were available for identification and date of surgery.

Other factors potentially predictive of breast milk feeding at discharge from maternity care that were available for analysis included: maternal age, country of birth, socioeconomic status according to the Australian Bureau of Statistics Index of Relative Socio-economic Disadvantage,10 marital status, urban or rural residence, private care, parity, multifetal pregnancy, antenatal care before 20 weeks’ gestation, smoking during pregnancy, morbid obesity, hypertensive disorders of pregnancy, diabetes (pregestational or gestational), labour analgesia, labour induction or augmentation, mode of birth, severe maternal morbidity,11 maternal postnatal length of stay, gestation, small for gestational age (< 10th birthweight for gestational age percentile), major congenital anomalies (eg, cleft lip or palate, spina bifida, tracheoesophageal fistula), neonatal intensive care unit admission, and perinatal mortality. These factors are known to be reliably reported.12

Statistical analysis

Descriptive statistics were used to summarise the distributions of maternal and pregnancy characteristics among all women with and without breast augmentation. Poisson regression modelling with robust standard errors13 was employed to determine the association of breast augmentation with (i) any breast milk feeding (compared with none) and (ii) exclusive breast milk feeding (compared with non-exclusive) among the “any breast milk feeding” group.

To avoid confounding by factors likely to be associated with reduced breastfeeding,14,15 regression analyses were limited to women who had a singleton infant with no major congenital anomalies and born at term (≥ 37 weeks). Crude and adjusted relative risks (RRs) with 95% confidence intervals were estimated for characteristics likely to be associated with breastfeeding.

Finally, among women with at least two births in the study period, we examined the primary and secondary breastfeeding outcomes across births in the following groups: no breast augmentation, breast augmentation between births, and breast augmentation before both births. The before-and-after effect of breast augmentation among women who had breast augmentation surgery between births was assessed using the McNemar test of paired data, with continuity correction.

Results

Of the 388 148 women who were eligible for the study, 902 had documentation of cosmetic breast augmentation surgery (Box 1). Breastfeeding information at discharge was missing in 9759 records (2.51%). Among the remaining 378 389 women, 892 (0.24%) had breast augmentation before a birth. The median age at the time of breast augmentation surgery was 28 years (range, 18–43 years), and the median interval between surgery and birth was 3.1 years (range, 1.0–10.1 years).

Maternal, pregnancy and birth characteristics for all women with and without breast augmentation are presented in Box 2. At discharge, 705 women (79.0%) with breast augmentation provided any breast milk to their infants, compared with 88.5% of women without breast augmentation.

Breast milk feeding outcomes were then assessed among 341 953 singleton infants with no major congenital anomalies born at term. Compared with women without, women with breast augmentation had reduced likelihood (adjusted RR, 0.90; 95% CI, 0.87–0.93) of feeding their infant with any breast milk at the time of discharge from birth care. Factors controlled for that were positively associated with breast milk feeding included: older maternal age, non-Australian-born, high socioeconomic status, nulliparity, non-smoker, no obstetric interventions, and longer hospitalisation after birth (Appendix 2). Women with breast augmentation in the 2 years preceding birth had similar rates of any breast milk feeding to women with a longer period since breast surgery (77% v 81%; P = 0.17).

For women whose infants received any breast milk, there was no association between breast augmentation and exclusive breast milk feeding. Among these, 593 women (94.0%) with breast augmentation exclusively breast milk fed. The adjusted RR for exclusive breast milk feeding among women with breast augmentation, compared to those without, was 0.99 (95% CI, 0.97–1.01).

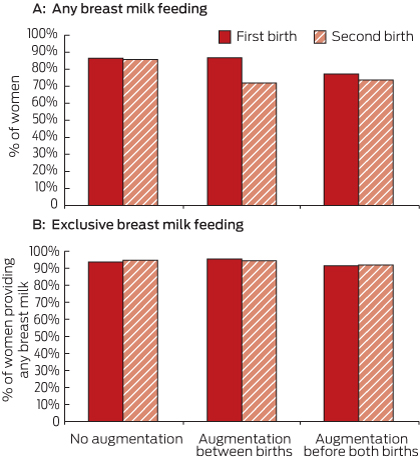

Among the 106 835 women with two births during the study period, 106 593 had no record of breast augmentation, 167 had breast augmentation before both births, and 75 had breast augmentation between the two births. The rates of any breast milk feeding and exclusive breast milk feeding at the first and second births were compared for these three groups of women (Box 3). The rate of any breast milk feeding was the same for both births among women with no augmentation (87%). Among women with breast augmentation between the births, the rate declined from 87% in the first birth to 72% in the second birth (P = 0.02). There was no evidence of significant change among women with augmentation before both births (77.2% v 73.7%; P = 0.29; Box 3, A). However, among women who provided any breast milk, the rate of exclusive breast milk feeding was similar in first and second births for women with and without breast augmentation (Box 3, B).

Discussion

This is the first study to document the population prevalence of cosmetic breast augmentation in a maternity population, and the largest to compare breast milk feeding outcomes for women with and without cosmetic breast augmentation. We found that women with breast augmentation are less likely to provide their infants with any breast milk at the time of discharge. However, among women who provide breast milk, women with breast augmentation are no more or less likely to exclusively breast milk feed their infants. Both the main population analysis and the subgroup analysis of women with breast augmentation between births showed lower rates of any breast milk feeding following augmentation surgery. This consistency of findings strengthens the case that there is an effect, although possible mechanisms are unclear.

Uptake of breast augmentation surgery is increasing, with 8000 Australian, 10 000 British and 307 000 American women undergoing the procedure in 2011.4–6 We found that 79% of these women can be expected to breast milk feed at discharge, compared with 89% of women without surgery. As maternity care affects breastfeeding success,2 these findings underscore the importance of identifying, supporting and encouraging all women who are vulnerable to a lower likelihood of breastfeeding.

Underlying breast hypoplasia and insufficient lactogenesis have been suggested as a reason for reduced breastfeeding rates among women with breast augmentation.16 However, we found that among women who had breast augmentation between births, any breast milk feeding fell from 87% in the “before augmentation” birth to 72% in the “after augmentation” birth, while the rates in comparison groups remained stable. A demonstrated ability to provide breast milk before augmentation surgery suggests that hypoplasia is not the explanation for lower breastfeeding rates among women with breast augmentation. Similar to the one existing population-based study,17 we found no association between breast augmentation and adverse birth outcomes, including preterm birth, small for gestational age, congenital anomalies, neonatal intensive care unit admission or perinatal death.

Lower breastfeeding rates may reflect maternal and family attitudes and expectations, may be a consequence of surgery, or the breast implants may reduce the ability to lactate. Although a variety of health outcomes have been investigated among women who have silicone breast implants, and their breast milk fed infants, epidemiological studies have not substantiated links with adverse outcomes.18–21 Nevertheless, women with breast implants may fear transmitting silicone or other breast implant materials into breast milk. They may also fear, or have been told by their surgeon, that breastfeeding could undo a satisfactory augmentation result. Another explanation is that lactiferous ducts, glandular tissue or nerves of the breast are damaged during surgery, or by pressure from the implants on breast tissue.22 Furthermore, complications of the surgery including capsular contracture, haematoma formation, infection or pain may reduce the ability or desire to breastfeed.22 Future qualitative research is needed to better understand why women with prior breast augmentation are less likely to breastfeed.

Our findings of reduced rates of any breastfeeding are consistent with the only study that reported rates of any breastfeeding after augmentation among women who attempted breastfeeding.16 However, the latter study reported a stronger effect at 2 weeks postpartum (RR, 0.67; 95% CI, 0.50–0.91). In contrast, our findings differ from the systematic review of three small studies, which found women with breast implants who breast milk fed were less likely to exclusively breastfeed.7 We believe our whole-population findings are more robust. The previous studies had selected populations (eg, lactation referral clients) and variable end points (eg, exclusive breastfeeding, insufficient lactogenesis), used historical controls and made limited attempts to control for potential confounders.7 However, it is possible that differences in the rates of exclusive breastfeeding may become apparent after discharge, as follow-up in the three studies was longer (minimum 2 weeks postpartum).

A strength of our study is the use of recent, large, linked population health datasets that include a third of all births in Australia. Breastfeeding information is reported by a midwife, and previous validation studies show events occurring around birth or immediately postpartum are well reported.12 Longitudinal record linkage allowed the ascertainment of cosmetic breast augmentation surgery. Although a longer lookback period may have increased case ascertainment,23 some missed cases among a population of more than 300 000 women without breast augmentation are unlikely to change the findings. Similarly, women who have cosmetic surgery overseas or interstate are not captured in this study. Identification of breast augmentation surgery in routinely collected data has not been evaluated but, in general, surgical procedures are reliably identified in hospital discharge data, and other breast surgery, such as mastectomy, is accurately reported (sensitivity, 97%; positive predictive value, 97%).12,24

Another strength is that breastfeeding was assessed at the same time for both exposed and unexposed women, unlike prior studies.7 The 89% breastfeeding rate at discharge in our study is similar to the rate reported in the Australian National Infant Feeding Survey (90.2% for < 1 month).25

However, information on breastfeeding initiation was not available. If women with breast augmentation initiated breastfeeding but gave up before discharge, the rate of exclusive breastfeeding could be lower if these women were included in the “any breastfeeding” denominator. Another limitation of the study is that breastfeeding is only assessed at one time point (discharge). Breastfeeding rates decline steadily over the first months of infancy25 and it is unclear whether this decay would be the same for women with and without breast augmentation. Information was not available on intention to breast milk feed, paternal support for breastfeeding, nor on the details of the breast augmentation surgery, such as the incision type or the type and volume of the breast implant.

An absolute rate of one in five women with breast augmentation who subsequently give birth may be unable or unwilling to breast milk feed their infants. This information should be provided as part of informed decision making to women contemplating breast augmentation surgery.

1 Study population flowchart, 2006–2011

2 Maternal, pregnancy and birth characteristics for participants, by breast augmentation status

| |

Breast augmentation (n = 892), no. (%)

|

No breast augmentation (n = 377 497), no. (%)

|

P*

|

|

|

Mother’s age at birth (missing = 106)

|

|

|

< 0.001

|

|

< 20 years

|

3 (0.3%)

|

15 406 (4.1%)

|

|

|

20 to < 35 years

|

608 (68.2%)

|

276 043 (73.2%)

|

|

|

≥ 35 years

|

281 (31.5%)

|

85 942 (22.8%)

|

|

|

Region of birth (missing = 1489)

|

|

|

< 0.001

|

|

Australia or New Zealand

|

761 (85.5%)

|

264 041 (70.2%)

|

|

|

Asia

|

45 (5.1%)

|

58 811 (15.6%)

|

|

|

Other

|

84 (9.4%)

|

53 158 (14.1%)

|

|

|

Married or de facto

|

718 (80.5%)

|

308 709 (81.8%)

|

0.32

|

|

Socioeconomic status (missing = 6140)

|

|

|

< 0.001

|

|

Most disadvantaged

|

103 (11.6%)

|

79 232 (21.3%)

|

|

|

Disadvantaged

|

134 (15.1%)

|

71 517 (19.3%)

|

|

|

Average

|

159 (17.9%)

|

75 027 (20.2%)

|

|

|

Advantaged

|

210 (23.7%)

|

71 656 (19.3%)

|

|

|

Most advantaged

|

282 (31.8%)

|

73 929 (19.9%)

|

|

|

Urban residence at birth

|

653 (73.2%)

|

263 218 (69.7%)

|

0.02

|

|

Private care

|

370 (41.5%)

|

120 211 (31.8%)

|

< 0.001

|

|

Nulliparous

|

378 (42.4%)

|

206 078 (54.6%)

|

< 0.001

|

|

Multifetal pregnancy

|

18 (2.0%)

|

5282 (1.4%)

|

0.12

|

|

First antenatal visit < 20 weeks’ gestation

|

834 (93.5%)

|

344 892 (91.4%)

|

0.02

|

|

Smoking during pregnancy

|

85 (9.5%)

|

45 073 (11.9%)

|

0.03

|

|

Hypertensive disorders

|

70 (7.9%)

|

38 568 (10.2%)

|

0.02

|

|

Diabetes

|

32 (3.6%)

|

26 621 (7.1%)

|

< 0.001

|

|

Morbid obesity

|

0

|

1277 (0.3%)

|

0.08

|

|

Regional labour analgesia

|

284 (31.8%)

|

101 925 (27.0%)

|

0.001

|

|

Labour induction

|

256 (28.7%)

|

103 368 (27.4%)

|

0.38

|

|

Mode of birth (missing = 287)

|

|

|

0.62

|

|

Unassisted vaginal

|

485 (54.4%)

|

210 506 (55.8%)

|

|

|

Instrumental vaginal

|

130 (14.6%)

|

51 447 (13.6%)

|

|

|

Caesarean section

|

276 (31.0%)

|

115 258 (30.6%)

|

|

|

Severe maternal morbidity

|

12 (1.4%)

|

6102 (1.6%)

|

0.52

|

|

Mother’s postnatal length of hospital stay

|

|

|

0.78

|

|

1–2 days

|

327 (37.2%)

|

132 944 (35.7%)

|

|

|

3–4 days

|

359 (40.8%)

|

157 913 (42.4%)

|

|

|

5–6 days

|

168 (19.1%)

|

70 634 (19.0%)

|

|

|

≥ 7 days

|

25 (2.8%)

|

10 869 (2.9%)

|

|

|

Preterm birth (< 37 weeks’ gestation)

|

61 (6.8%)

|

21 871 (5.8%)

|

0.18

|

|

Small for gestational age

|

75 (8.4%)

|

35 722 (9.5%)

|

0.28

|

|

Neonatal intensive care unit admission

|

119 (13.3%)

|

53 510 (14.2%)

|

0.48

|

|

Major congenital anomalies

|

36 (4.0%)

|

13 842 (3.6%)

|

0.50

|

|

Perinatal mortality

|

0

|

8

|

0.89

|

|

Infant feeding at discharge

|

|

|

|

|

Any breast milk feeding

|

705 (79.0%)

|

334 250 (88.5%)

|

< 0.001

|

|

No breast milk feeding (formula only)

|

187 (21.0%)

|

43 247 (11.5%)

|

|

|

Exclusive breast milk feeding among women who provided any breast milk

|

653 (92.6%)

|

308 552 (92.3%)

|

0.76

|

|

Breast-related readmission within 6 weeks

|

13 (1.4%)

|

4471 (1.2%)

|

0.42

|

3 Breast milk feeding outcomes for women with two births, showing the before-and-after effect of breast augmentation, 2006–2011

more_vert

more_vert