Breast cancer is one of the three most common cancers worldwide. Early breast cancer is considered potentially curable. Therapy has progressed substantially over the past years with a reduction in therapy intensity, both for locoregional and systemic therapy; avoiding overtreatment but also undertreatment has become a major focus. Therapy concepts follow a curative intent and need to be decided in a multidisciplinary setting, taking molecular subtype and locoregional tumour load into account. Primary conventional surgery is not the optimal choice for all patients any more.

Preference: Surgery

1175

[Correspondence] Preventing delirium: beyond dexmedetomidine

The incidence of postoperative delirium in elderly patients is very high, particularly in patients admitted to the intensive care unit (82%) and those who have undergone major orthopaedic (51%) or cardiac (46%) surgery.1 Postoperative delirium is associated with increased morbidity, mortality, and health-care costs; however, no preventive pharmacological strategies are available.1 A Lancet study by Xian Su and colleagues (Oct 15, p 1893)2 offers new hope. Treatment with dexmedetomidine in elderly patients admitted to the intensive care unit after non-cardiac surgery reduced the incidence of delirium from 23% to 9%.

[Correspondence] Preventing delirium: beyond dexmedetomidine – Authors’ reply

We thank Sinziana Avramescu and colleagues for their comments regarding the underlying mechanism of dexmedetomidine to reduce delirium in elderly patients in the intensive care unit after surgery. We agree that the reduction of delirium incidence seen after treatment with low-dose dexmedetomidine infusion might occur because of the drug’s neuroprotective effects, which have been well documented previously.1 In our previous study,2 these neuroprotective effects were shown to be mediated through α2A adrenoceptors.

Doctor as patient

DR RICHRAD KIDD, CHAIR, AMA COUNCIL OF GENERAL PRACTICE

In the week that the AMA released its 2017 Public Hospital Report Card, a dose of salmonella saw me experience first-hand the pressures that public hospitals are under, and appreciate the value of a GP home visit for urgent care in circumstances when you can’t access your usual GP.

I had flown into Canberra for a weekend meeting of the AMA Council of General Practice, already feeling unwell with established symptoms of food poisoning. I was becoming sicker and more dehydrated. With abdominal pain and rebound tenderness, I found myself at the local emergency department at 10pm on the night of my arrival.

During the next eight hours I got to see my hospital colleagues dealing with the pressures of managing multiple patients in varying states of illness and distress, with limited resources and a bed capacity unable to keep up with demand.

Here it seems the world revolves around assessing and prioritising the steady stream through the door, although things can quickly change when a major incident happens. While I was there, the deluge of more than 80 patients affected by a local bushfire appeared to almost overwhelm available resources. The doctors, nurses and other staff worked diligently to ensure that patients were seen as soon as possible but, on a night like this, benchmark targets seemed to have very little relevance.

Sometime around 5am, with blood cultures taken and intravenous rehydration commenced, a long awaited physical examination revealed that my earlier rebound tenderness had resolved although there was still significant point tenderness. With no acute abdomen I was discharged around 6am Saturday.

During the morning I deteriorated, with worsening diarrhoea, vomiting and abdominal pain. I desperately needed a doctor and did not want a return visit to the ED. It was time to call one of the after-hours GP services, which sent a GP to see me in my hotel room. Following a comprehensive examination, which revealed marked lower abdominal tenderness and a positive Murphy’s sign, I had a script for ciprofloxacin. Armed with this, some ondansetron and gastro-stop I tried to make my flight home only to be bumped because I was too sick. Following a visit to the after-hours chemist and after commencing my ciprofloxacin I finally turned the corner, improving enough to fly home Monday morning.

I understand the health system better than most and know how daunting it can be to navigate – particularly at times when your usual GP is not there to guide. This experience was a timely reminder of the challenges our patients experience when seeking care, and why the AMA’s advocacy for our profession and our patients is so important.

Besides getting a taste of what my patients experience when seeking care outside of surgery hours, this episode has also highlighted the importance of looking after our own health. I did try and soldier on for too long, not wanting to let my colleagues down.

We are not super human and we do get sick. When we are, perhaps we should consider what advice we would give a patient in the same situation. We need to be kind to ourselves and recognise when we need another’s medical expertise.

Public hospitals – funding needed, not competition

ASSOCIATE PROFESSOR SUSAN NEUHAUS, CHAIR, AMA HEALTH FINANCING AND ECONOMICS COMMITTEE

Under its terms of reference, public hospital funding is a key focus for Health Financing and Economics’ work. How funding arrangements affect the operation of public hospitals and their broader implications for the health system has always been an important consideration for HFE, and for Federal Council and the AMA overall.

The AMA Public Hospital Report Card is one of the most important and visible products for AMA advocacy in relation to public hospitals.

The 2017 Report Card was released by the AMA President on 17 February 2017. The launch and the Report Card received extensive media coverage.

The Report Card shows that, against key measures relating to bed numbers, and to emergency department and elective surgery waiting times and treatment times, the performance of our public hospitals is virtually stagnant, or even declining.

Inadequate and uncertain Commonwealth funding is choking public hospitals and their capacity to provide essential services.

The Commonwealth announced additional funding for public hospitals at the Council of Australian Governments (COAG) meeting in in April 2016. The additional funding of $2.9 billion over three years is welcome, but inadequate.

As the Report Card and the AMA President made very clear, public hospitals require sufficient and certain funding to deliver essential services.

“Sufficient and certain” funding is also the key point in the AMA’s submission to the Productivity Commission’s inquiry into Reforms to Human Services, in relation to public hospitals. The Commission is expected to report in October 2017.

As part of this inquiry, the Productivity Commission published an Issues Paper seeking views on how outcomes could be improved through greater competition, contestability and informed user choice.

While the AMA believes there is clearly potential to improve outcomes of public hospital services, its submission highlighted that there are significant characteristics of Australia’s public hospitals that must be taken into account.

Health care is not simply a “product” in the same sense as some other goods and services. Public hospitals are not the same as a business entity that has full or even substantial autonomy over their customers and other inputs, processes, outputs, quality attributes, and outcomes.

Public hospitals work on a waiting list basis, usually defined by acuity of need, to manage demand for public hospital services. Private hospital services typically use price signals. There is limited scope to apply mechanisms for patient choice (such as choice of treating doctor) to access arrangements in public hospitals that are governed by waiting lists.

Public hospitals also operate within a highly developed framework of industrial entitlements for medical practitioners and other staff that are tightly integrated with State/Territory employment awards. These measures are intended to encourage recruitment and retention of medical practitioners to the public sector, offering stable employment conditions, continuity of service and portability of entitlements. They support teaching, training and research in the public sector as well as service delivery.

The freedom to choose between public and private hospital care, and the degree of choice available to patients in public hospitals as distinct from private patients, is an integral part of maintaining Australia’s balanced health care system. The broad distinction between public and private health care is generally understood by the community as a basic feature of the health system and part of Medicare arrangements, even though detailed understanding of how this operates, including what they are actually covered for in specific situations, is often lacking for many people.

Introducing private choice and competition elements into public hospital care will tend to blur the distinction between public and private health care, and reduce the perceived value of choice as a key part of the incentive framework for people choosing private health care.

The Commission’s Issues Paper proposes that increased competition will address equitable access for groups including in remote areas, benchmarking and matching of best practice, and greater accountability for performance. These are all worthwhile and important objectives in their own right. As such, they are already the focus of a range of initiatives.

Public hospitals are already subject to policies and requirements that address the same ends of improved efficiency, effectiveness and patient outcomes, including:

- Hospital pricing, now supported by a comprehensive, rigorous framework of activity based funding and the National Efficient Price;

- Safety and quality, supported by continuously developing standards, guidelines and reporting, including current initiatives to incorporate into pricing mechanisms;

- Improved data collection and feedback on performance including support for peer-based comparison.

The single biggest factor that will increase the returns from such initiatives is the provision of sufficient and certain funding. Increased competition, contestability and user choice will not address this need.

The AMA Public Hospital Report Card 2017 is at ama-public-hospital-report-card-2017

[Perspectives] Listerism then and now

In March, 1867, Joseph Lister (1827–1912) published a paper in The Lancet announcing his antiseptic system for healing wounds. His discovery changed medicine and surgery— eventually. To mark the 150th anniversary of this publication, we examine the establishment and evolution of germ-free surgery, from Lister’s time through the antibiotic era.

Outstanding doctor from outstanding Israeli hospital visits Down Under

Internationally renowned Israeli doctor Nitza Heiman Newman is currently visiting Australia representing the Soroka Medical Centre, the only major medical centre in the entire Negev.

It is one of the largest and most advanced hospitals in Israel, serving a population of more than one million people, including 400,000 children, in a region that accounts for more than 60 per cent of the country’s total land a

Soroka also serves as a teaching hospital of the Ben-Gurion University Medical School.

But what makes Soroka even more unique in the region is that in a nation often embroiled in conflict, it caters for everyone.

“We treat people by the severity of the medical problems they have, not by any religion or culture,” Dr Newman said.

“You can see in our wards, in the same room, Israelis, Jews, Arabs, Bedouin and more.

“And you can see the changes of the people in those wards. It can sometimes start out with – I wouldn’t say with tension, but maybe with some suspicion amongst the patients and those who visit them. But within 24 hours they are getting along better and visitors are often bringing along cakes for everyone in the room.”

Another thing making Soroka a standout facility is the way it is prepared for trauma. In a war zone, this is a necessity.

“What we see a lot of unfortunately is military trauma in our area. The last time there was a serious breakout two years ago our helipad was very, very busy and we were treating a constant flow of injured soldiers and civilians,” Dr Newman said.

“We are one of the biggest medical centres in Israel and definitely as a trauma centre. But we are also a general hospital with more than a thousand beds.

“We do everything, including transplants. Our specialty is genetics and we also have the biggest delivery room in the country – delivering 55 new babies every day.”

Dr Newman says Soroka is an example to the world, which is part of her reason for being in Australia.

She is speaking at forums about the medical centre and also about the United Israel Appeal program called Professions for Life, which assists new immigrants to Israel to re-certify in their chosen professions.

“If you make the transition easier for new immigrants you make their lives easier and they integrate faster,” she said.

“It makes life more enjoyable for them and for those who absorb them into the community.”

Born in Israel, the only child of Holocaust survivors, Dr Newman served in a range of positions in the Israel Defense Forces, including as an officer in the Golani Brigade. Her last army position was as a company commander in a female officers’ course.

She took a year off from medicine to direct a school in Be’er Sheva for gifted children, before taking a residency in pediatric surgery at Soroka Medical Center in Be’er Sheva.

She then did a year-long fellowship at Great Ormond Street Hospital in London in the field of pediatric oncology surgery, a field that she developed at the hospital.

Since 2005, Dr Newman has been responsible for the Dr. Gabi and Eng. Max Lichtenberg scientific program in surgery for outstanding staff at Ben-Gurion University.

From 2009-2013, she was a member of the Be’er Sheva city council and responsible for the health and environment portfolio.

Since 2010 she has been the deputy hospital director, in charge of medical personnel, children’s division, maternity division, gynecology, psychiatry and now rehabilitation as well.

Chris Johnson

Variation in the costs of surgery: seeking value

Transparency is key to achieving affordability of health care

There is increasing concern about the sustainability of health care in Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) countries. Australia currently spends US$6140 per capita — or 9.1% of its gross domestic product — on health care.1 Moreover, there is evidence that health care costs, including out-of-pocket (OOP) expenses, are rising.2 In Australia, 68% of health care costs are funded through the public health system, with 32% from other sources, including private health insurers and OOP expenses.2 To encourage Australians to take out health insurance, the private health system is subsidised by a private health insurance rebate, which costs the public about $5 billion per year.2 Private health insurers derive their income from premiums, which have risen an average of just under 6% per year since 2012, well above the inflation rate or the consumer price index.3 Individual OOP expenses are also rising at an average rate of 6.2%; they have more than doubled in a decade and accounted for 17.8% of Australia’s $140 billion health care spending in 2013–14.2

Value is defined as the health outcomes achieved per dollar spent.4 Moreover, data on performance and outcomes are fundamental to the ability to determine value. Reports on variation across the country,5 including comparison with other OECD countries,6 may prompt a review of activity (the treatments and procedures the health system provides), but cannot determine their value without measurement of costs and outcomes.

To ensure high value, the procedures performed must be appropriately indicated, avoiding overservicing or selecting a particular treatment when its likelihood of success, compared with the alternatives, is limited. Health professionals have an ethical responsibility to avoid waste in health care — not only by better targeting resources, but also because “useless tests and treatments cause harm”.7

The interim report on the Medicare Benefits Schedule (MBS) review8 highlights a recurring theme of how to better inform the system through stakeholder feedback based on contemporaneous data. There is currently limited use of health care data, a lack of meaningful clinical reports and often a failure to engage clinicians in clinical governance. This includes costs and fees charged across the health system and informing consumer choice.

The Royal Australasian College of Surgeons (RACS) and Medibank, Australia’s largest private health insurer, have published reports on surgical variance, which detail the cost and outcomes of care in selected high volume procedures for general surgery, otolaryngology, urology, orthopaedics and vascular surgery.9

Data sources and analysis

The data in the reports were extracted from administrative claims — received by Medibank from private hospitals and specialists — for treatment provided to Medibank policy holders. This initial analysis looked at hospital separations with an admission date in 2014 and any follow-up hospital separation funded by Medibank within 6 months of discharge. The reports were compiled from hospital claims data, hospital casemix protocol data and MBS data relating to diagnoses, interventions and patient demographics. We analysed service use, including transfers to intensive care units (ICUs) and rehabilitation, and plotted outcomes based on length of stay, hospital acquired complications, re-admissions and re-operations. The data on costs included the Medicare item numbers billed, total costs of a hospital admission, cost of prostheses, and OOP expenses.

Procedures were identified by MBS code and selected on the basis of volume to ensure a sufficient spread across surgeons performing them. A principal procedure was identified for each hospital separation, and for most of them, this was the highest value MBS item fee from the medical claim. Where multiple MBS codes described a single procedure, the similar MBS codes were combined. Surgeon level analysis was limited to those with at least five procedures in the dataset. Medibank did not share the identity of the individual surgeon.

Hip replacement as an example

The RACS and Medibank reports on clinical variation focus on specific surgical procedures without risk adjustment.9 For patients who had hip or knee arthroplasty, there was wide variation in the length of stay, use of ICU bed days or rates of transfer to inpatient rehabilitation.

We have used hip replacement as an example in our discussion of costs, fees and value. The rates of hospital acquired complications were reassuringly low.

The cost of a surgical episode of care includes the sum of hospital, surgeon and other providers’ fees, the prosthesis, and pharmaceuticals. The use of ICU after the operation or transfer to rehabilitation following a surgical admission varied considerably. For the 299 surgeons who performed at least five procedures, the average separation cost of a surgeon ranged between $18 309 and $61 699 with a median of $26 661 (the average total cost per hospital separation was $27 310). High volume surgeons showed greater congruity and were closer to the median in terms of the overall cost of a hip replacement. There was little variation in regional (state and territory) total costs.9

Prices for hip prostheses varied from $4908 and $16 178, with a median of $10 727 (Box 1). In Australia, there is considerable disparity in the cost of prostheses when prices are compared between the public and private health systems.10 The amount paid by private health insurers for a prosthesis in the private sector can be twice the amount in public hospitals. Australia also pays a high price for prostheses when compared with other OECD countries.10 The government has recently announced a reduction in the price to be paid for items on the Prostheses List, reducing a hip prosthesis by 7.5%.11

OOP expenses

Medical practitioners in Australia, including surgeons, often augment the fee paid by Medicare and the private health insurer with a copayment paid by the patient. This is known as an OOP charge and is often resented by patients with private health insurance. There is considerable variability in the rebate a health fund will reimburse with regards to a provider’s fee and, therefore, some difference in gap payments is to be expected.

Medibank-insured patients who had a hip replacement incurred an OOP charge by the principal surgeon in 39% of separations, and the average OOP fee was $1778.9

For the 299 surgeons who performed at least five hip replacements, 142 (47%) did not charge any OOP. The average OOP charged ranged from none to $4057.9 The OOP surgical fee is a large but not the only component of gaps paid by patients. OOP charges for other medical services, including charges raised by the anaesthetist, assistant surgeon, and for diagnostics, were charged in 80% of the hospital separations, with an average charge per patient of $342.9

What is a reasonable fee?

The RACS recognises — as does the Australian Medical Association — that gaps are necessary and that, apart from the variability in insurance coverage, the underlying cause of gap fees is the failure of government reimbursement through Medicare to keep pace with inflation and the cost of providing a service.12 The RACS view is that the fees charged should be reasonable and in line with the skill, effort and risks associated with performing a procedure and providing perioperative care.13

Surgeons should not take advantage of the vulnerability of their patients. No one should need to access their superannuation, remortgage their home or resort to crowd funding to have surgery that is clinically indicated. In Australia, the public system is always available for emergency and urgent surgery. RACS has made explicit statements in this regard, published position statements12,13 and provided advice to patients. The RACS code of conduct14 makes clear what is expected of surgeons in setting and informing patients about fees.

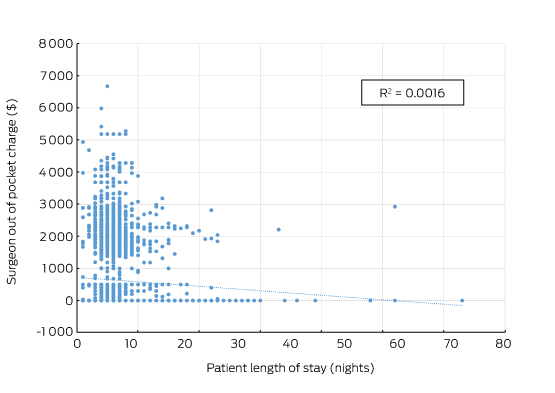

There was also no correlation between the size of the fee charged and the quality of the surgery. Indeed, an unpublished analysis by the RACS and Medibank found that surgical fees charged were not correlated with the length of stay for any procedures studied (Box 2). Length of stay is a reasonable surrogate for quality in well defined, largely standardised unicomponent elective operations, such as joint replacement, which have well established post-operative and discharge protocols.

There is an opportunity to further reduce the length of stay after a joint replacement when comparing the Medibank Private results with the public sector in Victoria15 and Scotland.16 This reduction may be achieved without diminishing the quality; a shorter stay may make savings and increase in value.

Conclusion

The discussion around the affordability of health care must continue. As key members of the health care team, surgeons cannot ignore the total costs of surgical services, the components within that service or the fees associated with their individual activity. The Medibank and other administrative datasets inform us on variation in the components of value — clinical activity, outcomes, reimbursements and costs. Making the reports publicly available9 provides assurance of transparency and accountability and may better inform surgeons’ and patients’ choices in the future.

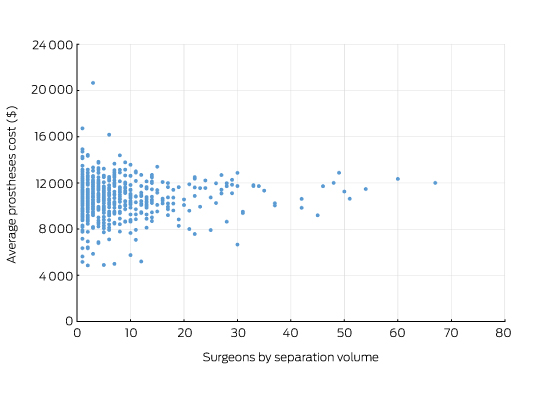

Box 1 –

Average prosthetic cost for hip replacements

Source: Royal Australasian College of Surgeons and Medibank Surgical Variance Report for Orthopaedic Surgery.9 The data cover the claims paid by Medibank for Medibank policy holders during 2014. Separations that included either Medicare Benefits Schedule items 49318 or 49321 were recorded as the highest value procedural item on the medical claim.

Box 2 –

Total knee replacement: plot of the out-of-pocket fee charged by the surgeon and hospital length of stay showing no correlation

Source: Royal Australasian College of Surgeons and Medibank. The data cover the claims paid by Medibank for Medibank policy holders during 2014. Separations that included either Medicare Benefits Schedule items 49518 or 49521 were recorded as the highest value procedural item on the medical claim.

Understanding the language of intensive care physicians

In the United States, surgeons (also known as surgical intensivists) often directly manage patients in the intensive care unit (ICU). Taking this into account, and despite the need to “translate” words such as “epinephrine”, “norepinephrine” and “respirologist”, I approached The surgical critical care handbook as an Australasian surgeon wishing to be conversant in the language of the intensivists to whom I entrust the care of my critically ill patients. In that respect, the book edited by Jameel Ali, Professor of Surgery and Advanced Trauma and Director of the Life Support Program at the University of Toronto, is generally fit for purpose, written in a broadly conversational style by a number of expert contributors. While not overly burdened with levels of evidence or results of randomised controlled trials, sufficient references are nonetheless provided to direct readers to the scientific background or details of operative surgery.

In a conventional conceptual framework, the book comprises two sections. “General considerations” deals largely with the various aspects of management that constitute critical care, including ethical considerations, and also involves a modicum of theoretical underpinning in respiratory physiology. “Specific surgical disorders” is a series of chapters on the pathophysiology, investigation and treatment of traumatic and non-traumatic conditions that require critical care.

The information provided in The surgical critical care handbook is as up-to-date and clinically applicable as it can be. It is reassuring to see mention of issues of increasing topical interest, such as bariatrics, transplantation and iatrogenic coagulopathies. Topics that may have needed a more in-depth discussion include chronic liver disease or liver failure in the surgical patient, major vascular injuries and other vascular pathologies, and penetrating neck trauma. Where relevant, details of surgical procedures in ICU patients are provided in sufficient detail, although the ICU-naive probably would have appreciated some specific chapters on inotropic support and monitoring modalities.

In the Australian setting, this book may be a useful resource for practitioners such as rural generalists. Surgical trainees may also find it a user-friendly aid to examination preparation and as a quick reference for problems encountered in everyday practice.

Murphy’s sign

A common abdominal examination manoeuvre, but a common understanding is elusive

Most of us think that Murphy’s sign consists of the abrupt interruption of deep inspiration when palpating in the right upper quadrant of the abdomen. Its relevance would seem to be its presence in a non-tender abdomen, but is that so? Canvass your colleagues and you will find that a common understanding is as elusive as the Scarlet Pimpernel. The radiological community’s development of a “sonographic” Murphy’s sign has only added to the confusion.

John B Murphy (1857–1916) was a Chicago surgeon practising at the turn of the 20th century. Diagnostic investigations were limited, and the task of differentiating between different abdominal emergencies was difficult. Murphy described several clinical tests to aid in differential diagnosis, but the sign he is best remembered for was first described in 19031 and was further expounded on many occasions in his journal Surgical Clinics of John B. Murphy (a forerunner to Surgical Clinics of North America).

Murphy described two signs for cholecystitis. The one that bears his name he called “deep-grip palpation”; the other, which he considered to be an even better test, was referred to as “hammer-stroke percussion”.2,3

Deep-grip palpation was performed by standing directly behind the seated patient, but if the patient was unable to sit up, “the examiner reaches over the recumbent patient from the head”.2 Murphy’s 1903 description continues:

The most characteristic and constant sign of gall-bladder hypersensitiveness is the inability of the patient to take a full, deep inspiration, when the physician’s fingers are hooked up deep beneath the right costal arch below the hepatic margin. The diaphragm forces the liver down until the sensitive gall-bladder reaches the examining fingers, when the inspiration suddenly ceases as though it had been shut off. I have never found this sign absent in a calculous or infectious case of gall-bladder or duct disease.1

He further elucidated in 1914:

Hook your fingers under the costal arch and ask the patient to take a full inspiration, then with the other hand strike the flexed fingers at the height of inspiration. If pain is elicited, it is a positive sign that the gallbladder is distended. That is not as good a test, however, as the perpendicular finger percussion test. That is the best test of all. Place your middle finger, held straight and rigid, at the tip of the ninth costal cartilage, and ask the patient to take a full inspiration with the eyes closed. When the height of inspiration is reached, strike a sharp blow on the finger. If the gallbladder is distended or the seat of inflammation, the pain elicited is severe.4

Over the years, the percussion test has been forgotten and Murphy’s sign now refers to deep-grip palpation. Today it is not acceptable to unnecessarily cause or exacerbate severe pain, and although it was used by Murphy in cases of acute cholecystitis, the passage of time has seen the sign modified to fit with modern clinical practice. If a patient has tenderness or guarding, he or she has clinical signs warranting investigation so why would we need a special sign? What use would it be and why would we even try to elicit it when we know it will cause further pain?

The surgical community has long recognised that the real usefulness of the sign is in the non-acute patient where there is no tenderness.5,6

How good a predictor is it? A study that looked at this using non-filling of the cystic duct on biliary scintigraphy as a surrogate indicator of acute cholecystitis found that it was both sensitive (97.2%) and highly predictive (93.3%) of a positive result.7 Another group found the test to be not so accurate in older people.8 Both of these studies used the sign in situations where there were likely to be other signs of acute inflammation.

The sonographic Murphy’s sign creates further confusion as it is something totally different from the common interpretations of Murphy’s sign discussed above.9,10 The sonographer asks if the pain is worse than anywhere else when pressing directly over the gall bladder. The technique does not rely on an involuntary reaction, and the patient holds his or her breath. Its only similarity to anything that Murphy described is that it is like his hammer-stroke percussion technique but with the percussion replaced by sound waves. Why Murphy is referred to in this test is puzzling. A simple description that the gall bladder was tender to probe pressure should suffice.

more_vert

more_vert