Engaging with patients to gain an in-depth understanding of their preferences, beliefs, values and contexts facilitates delivery of safe, high-quality care.1 Patient-centred care2 and being responsive to patient needs and desires is an international concept that is well recognised in the patient safety and health care quality literature.1

The importance of obtaining patients’ views about the health care they receive has been endorsed through the promotion of the Royal Australian College of General Practitioners standards.3 For accreditation to the standards, practices must regularly use an approved patient feedback tool, and must have a process for receiving and managing patient complaints.3 While such feedback enables comparisons at a health system level, it does not elucidate how patients think about safety and their involvement in health care. Qualitative methods can be used to uncover the complex, multifaceted issues concerning patients’ views of safety and quality in health care.4

In Australia, there has been ample research on patient preferences regarding quality of care in general practice5–10 and what constitutes the major incidences and causes of harm in this setting.11 Additionally, there has been some work on understanding what Australian patients know about problems and failures in health care,12 and adverse event and incident disclosure.13 A recent review found that only a small number of qualitative studies have been conducted with rural populations concerning quality of care, but none has focused on patient perceptions of safety in general practice.14 It is important to understand rural patients’ perspectives of safety, as they may have specific needs or different perspectives from urban populations.

With this in mind, we aimed to explore patients’ and carers’ experiences of rural general practice and to identify their perceptions of safety in this health care setting. We chose to conduct focus group interviews to gain a rich understanding of people’s attitudes, beliefs and views about their lived health care experiences.15

Methods

We targeted rural and regional patients and carers from south-west Victoria who were frequent users of general practice, such as those with a chronic condition, on repeat medication, older people and mothers with children. These patients were believed to have more experience with general practice, and therefore to have greater insight into specific safety issues.

Participants were recruited through local community health or allied health organisations between August and November 2012. Recruitment sources comprised education and support group meetings for type 2 diabetes self-management, cardiac rehabilitation, group exercise and a mothers’ group. Individuals were provided with study material, and if they were interested, they self-selected into the study.

The Flinders University Social and Behavioural Research Ethics Committee granted ethics approval (project no. 5667). Participants provided informed written consent and received a $50 shopping voucher for their time and travel expenses.

Focus group protocol

We conducted a series of focus group interviews between September and December 2012. They were recorded and transcribed verbatim. We administered a questionnaire to obtain basic demographic information before the start of each focus group.

A semi-structured focus group interview protocol was developed to gain a broad understanding of patients’ and carers’ experiences of care (Box 1). This exploratory study required a flexible approach and the use of general concepts that could be further refined and revised during data collection. Questions were adapted and follow-up questions were asked to probe particular safety points of interest from previous focus groups, and to confirm or contest these issues.

Focus group data were analysed using a thematic and iterative approach to identify the safety issues evident in participants’ narratives. Narrative analysis was used to explore and interpret the lived experience of individuals.16

Transcripts were reviewed by two authors (A L H and C W) and analysed using the constant comparative method to inductively generate a coding structure that outlined themes and subthemes. After the researchers reached consensus on the coding structure, the codes were applied to the entire set of interviews. NVivo 10 (QSR International) was used to support the analysis.

Results

During recruitment, 114 individuals were approached, with 32 providing consent. Twenty-six participants took part in one of four focus group interviews in the Victorian towns of Balmoral, Hamilton, Merino and Portland. Each group had three to 10 participants. Reasons for not participating in the focus groups included being too ill to attend, not able to attend at the specified time and date, loss of interest, and failing to attend. Box 2 shows participants’ demographic characteristics.

Participants who had experienced some level of harm were able to comment more extensively on safety aspects of care; however, themes related to safety were identified from the analysis of all participant narratives. Box 3 provides illustrative quotes associated with the key themes.

Risk awareness

Although not explicitly recruited with these criteria in mind, there were two types of participants — those who had experienced harm and those who had not. Harm was experienced in hospital care and general practice care, with the former being more common in the participants’ stories. The severity and seriousness of the circumstances that led to hospitalisation and the errors that occurred during the hospital journey created a heightened sense of awareness for safety in the hospital. Compared with hospital care, perception of risk in the general practice setting was perceived differently by some participants. Continuity of care and trust in the doctor–patient relationship allayed perception of risk.

Trust

Participants spoke of the characteristics of GPs that contributed to a sense of trust, which included confidence in their clinical competence and having personal knowledge of the patient.

When participants had experienced harm in general practice, their trust was compromised to varying degrees. Some patients took action to rebuild this trust, while others ended their relationship with that GP and sought care elsewhere.

Participants who had not experienced harm relied heavily on their trust in provider. Some were forthcoming about their lack of knowledge or understanding of safety, and their limited ability to accurately identify when risks could occur. Experience and expertise of the GP were additional factors which promoted trust.

Vulnerability

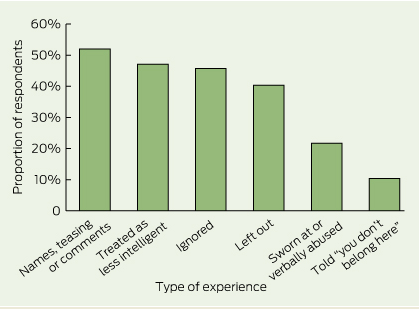

Participants described feelings of vulnerability in their experiences of care. Many suffered from multiple chronic conditions and therefore considered themselves more at risk of harm, whether these were clinical or psychological harms. Reported clinical harms included misdiagnosis, delays in treatment, not adhering to standard care procedures, and medication errors. Psychological harms that some participants experienced included verbal abuse, name calling and other disrespectful or dehumanising behaviours or practices such as lack of eye contact, and dismissive, rude or aggressive interactions.

Even participants who had not experienced harm emphasised their need to be treated with respect as an individual by the GP, demonstrating a collective sense of vulnerability faced by the general population of patients.

The power dynamics between the patient and the doctor also contributed to patient vulnerability. When participants attempted to voice their real or perceived fears about their health conditions to their GP, power imbalances between patient and provider led to feelings of embarrassment and foolishness.

A forgiving view of mistakes

Some participants considered mistakes or errors in their care as “normal”. They expressed an understanding and sympathy towards the GP’s situation and considered mistakes as part of being human. Many viewed the GP as an ordinary person in their community, not “god-like” or omnipotent.

The familiarity and continuity of the doctor–patient relationship in general practice may have enhanced this forgiving view of mistakes, when compared with one-off and short encounters with health professionals in hospital settings. The sense of closeness experienced in a rural community may also account for the differential tolerance of hospital versus GP mistakes.

Desire for an explanation and apology

Participants lacked appreciation of the systemic nature of medical error, and as a result they placed responsibility for errors solely on the GP. In contrast with accountability for errors, participants described system barriers that prevented GPs or other health care professionals from apologising and acknowledging patient harm, including a medical culture fearful of litigation.

Nevertheless, they reported a need for an explanation of what went wrong and why, and they described apology as the most effective way for patients to recover and move on from an incident. Some participants described feelings of admiration for those clinicians who apologised to patients when errors occurred despite the perceived threats of litigation.

Appreciation of general practitioner interpersonal skills over competence

Some participants did not focus on the safety of their care, but rather the GP’s interpersonal skills. In these instances, participants appeared to value the interaction and relationship with their GP without seeming to question the GP’s clinical competence. A desire for a caring GP and other relational attributes were considered to be more important, and care was assumed to be safe.

Discussion

Our study aimed to identify patients’ perceptions of safety in general practice and explore the factors contributing to the development of these perceptions. Many of the participants had an assumed sense of safety in the rural general practice setting. Only those who had experienced harms were able to comment extensively on safety, and much of this concerned experience with or awareness of hospital safety issues. Those who had not experienced harm did not conceptualise it, and furthermore, when these participants were in a trusting relationship with their GP, they assumed that the care provided was safe.

These findings directly contest previous research, which found that patients who have experienced harms in hospital settings could accurately identify and report on safety incidents,17,18and make recommendations on improvements to safety.12 Even the general public have an awareness and understanding of safety in health care due to increased amount of research, media attention, and political interest in recent years.19 However, much of this research has occurred in hospital settings and may not be applicable to the general practice setting, where issues of trust, vulnerability and preferences for interpersonal skills are prominent over safety.

Individual contribution at the beginning and throughout the focus group discussions was emphasised through the use of a skilled facilitator to minimise agreement bias. Interpretation bias was acknowledged and avoided through independent data review and analysis. Although there were only 26 participants, the issues raised reflected a diversity of views and experiences.

An assumed sense of safety is a concern, given that general practice is the first point of contact for most people seeking medical care, and its high volume of repeat interactions and frequency of adverse events.20In our study, risk perception in general practice was mediated by a variety of different factors. Trust was the most prominent factor, and it may mask the patient’s ability to identify possible threats to safety and hence reduce risk awareness. Trust in the patient–provider relationship has been researched,21 and has been used as a model to improve patient involvement in safety, with mixed results.22,23 The nature of general practice makes it amenable to the creation of trusting relationships between patients and doctors. However, patients reverting to a default position of trust when they believe they do not have sufficient knowledge or skills, or are not in a position to adequately comment on safety,24 is problematic because patient awareness of and involvement in safety has been shown to improve clinical effectiveness, health outcomes and satisfaction with care.25

This study also revealed unique safety-related themes. Feelings of vulnerability have been reported by patients with chronic diseases.26 Interaction and communication between the patient and the GP is important to reduce feelings of vulnerability and ensure that patients feel comfortable and confident with their GP. Effective communication during the consultation is the key to facilitating safe and high-quality care; however, there is no “one size fits all” approach, as patients’ preferences and desires for a style of interaction vary widely. Being flexible and adaptable to patients’ different communication needs has been recommended as a solution to the limitations of general communication guidelines.27 Further, communication with patients extends to the disclosure of errors when they occur. Patients in our study and in others28 expect an honest and timely apology where appropriate and explanation of what went wrong. While there is a code of conduct in Australia referring to open disclosure of medical errors, there are still gaps in compliance and patient satisfaction with this process.13

We found that only patients who had experienced harm were able to comment on safety issues, and safety was largely seen as a problem in secondary care. New insights into the factors that influence the development of safety perspectives have demonstrated the value of incorporating the patient voice into safety research. These findings contest current research on patient involvement in safety, and warrants further exploration.

1 Focus group interview questions and prompts

The primary questions posed in the focus groups were:

1. Can you describe what is involved in a normal visit to your general practitioner?

Prompts: Ringing to make an appointment, arriving at the

clinic, waiting time

2. Can you describe your relationship with your GP?

Follow-up question: What makes a good relationship?

Prompts: Communication, trust, information provision

3. What other staff do you come across at the GP clinic?

Prompts:Reception staff, practice nurse, practice manager

4. Is there anything about the clinic that influences you wanting to go there?

Prompts:Car parking, disability access, cleanliness

5. What is most important to you about the care you receive at your GP clinic?

Prompts:Patient-centred care, patient involvement in care

6. If you could improve something about the care you receive, what would it be?

Prompts:What do you do when things go wrong?

Prompts:Awareness of safety issues, risk perception

2 Demographic characteristics of the 26 focus group participants

|

Characteristic

|

|

|

|

Women, no. (%)

|

14 (54%)

|

|

Pension card holder, no. (%)

|

18 (69%)

|

|

Health care card holder, no. (%)

|

15 (58%)

|

|

Married, no. (%)

|

16 (62%)

|

|

Secondary education (years 7–10), no. (%)

|

10 (38%)

|

|

Retired, no. (%)

|

15 (58%)

|

|

Repeat prescription, no. (%)

|

18 (69%)

|

|

Common health conditions, no. (%)

|

|

|

High blood pressure

|

11 (42%)

|

|

High cholesterol

|

10 (38%)

|

|

Arthritis

|

10 (38%)

|

|

Mean age in years (SE); range

|

59 (3.8);

range, 27–83

|

|

Mean number of health conditions (SE); range

|

3 (0.6);

range, 0–14

|

|

Mean number of visits to general practitioner in previous year (SE)

|

12 (2.3)

|

|

|

SE = standard error.

|

3 Participant quotes associated with safety themes

Risk awareness

If I know I’m being looked after I feel safe. Like if I know, all right, they may not have all the answers but people are onto it … people are working together with me and then I feel safe. Whether it’s like my current doctor who doesn’t know anything much about my condition anyway, but he’s working together with my cardiologist and they’re working it out together and so I feel quite, far safer than I have in a very long time so. But not so with the hospital. That’s a different thing. (37-year-old woman with a congenital chronic condition)

[Hospital acquired infections] are the things you see in the major hospitals that cause havoc. Where … what you end up with is worse than what you went in with. (83-year-old man with multiple chronic conditions)

Trust

The thing is … when you don’t have confidence in a doctor either a) because of something they’ve done or b) because you don’t know them, it makes life even that more difficult. (69-year-old man with multiple chronic conditions and a carer)

Conversation between two participants:

P1: You don’t know I don’t reckon … I’m just like “whatever” you know like I didn’t want to be there so they kept coming and saying “oh we’ll try this”, and I’m like “yep whatever go for it”, you know … (27-year-old mother)

P2: You trust, yeah. (28-year-old mother)

P1: … you just “OK”, you’re just in there, you know, emotional to say the least … you have no idea what’s about to happen … Well they’re doctors and they’re nurses and they’ve probably done it 100 times before, they all know. You just go with it, like that’s me and I’m one of those personalities to just say “yep, yep OK”. I just trust that they know what they’re doing.

Vulnerability

… [we] told her that his bowel habits had got worse, they changed, he wasn’t feeling that well and everything. And he said I wouldn’t mind a colonoscopy and she’s saying “you don’t need it, I’ll give you something else for your haemorrhoids”. After she finished we were getting ready to leave and he said “I’d really like a colonoscopy” and I can still see her sitting there, she was kinda half turned her back to us with the computer and she looked over like that [over shoulder] and she said “I cannot send you for a colonoscopy like that for haemorrhoids” … he felt really stupid for asking then … We did feel rather foolish the way she spoke with us … (64-year-old woman carer)

Conversation between two participants:

P1: You’re vulnerable. You’re vulnerable to them … (37-year-old woman with a congenital chronic condition)

P2: Yeah, yeah. (73-year-old man with multiple chronic conditions)

P1: And you’d prefer if they don’t abuse that …

P2: We’re pretty frail creatures, aren’t we, when it comes to sickness?

A forgiving view of mistakes

I felt that, ah, more should have been done when I went to doctor for a respiratory problem … Not a sign of sounding me or doing anything like that, but he was busy and as I was told he was having a bad day, and the phone had gone out and a few things like that. Well OK, he’s only human. (83-year-old man with multiple chronic conditions)

Desire for explanation and apology

I’d prefer someone to say to me “look I’ve made a booboo”, “yes you’re right”, “OK, we’ll make sure that doesn’t happen again”. All over red rover. (73-year-old man with multiple chronic conditions)

Conversation between two participants:

P1: Like, I feel like you need an explanation and why everything went chaotic. I think they should explain this is what happened. They can’t tell you at the time because it’s all happening. (28-year-old mother)

P2: No, nobody was telling me anything. (35-year-old mother)

P1: But afterwards I think you definitely need a, your doctor should debrief you and say this is what is happening; this is why we did this and that.

Appreciation of general practitioner interpersonal skills over competence

… so I went to there and, um, this fella was a lovely fellow but he had no idea about five of the illnesses that I had suffered from. He had no idea about what medications I ought to take. He still doesn’t figured out what the blood tests I get for the leukaemia, and um, so you know, that’s where, but he is a lovely fellow, and I love going to him because we have a good chat … (70-year-old man with multiple chronic conditions)

more_vert

more_vert