Twenty years after the Port Arthur massacre and the National Firearms Agreement (NFA), it is timely to examine how assertive national firearms regulation has prevented firearm mortality and injuries, and gun lobby claims that mental illness underpins much gun violence.

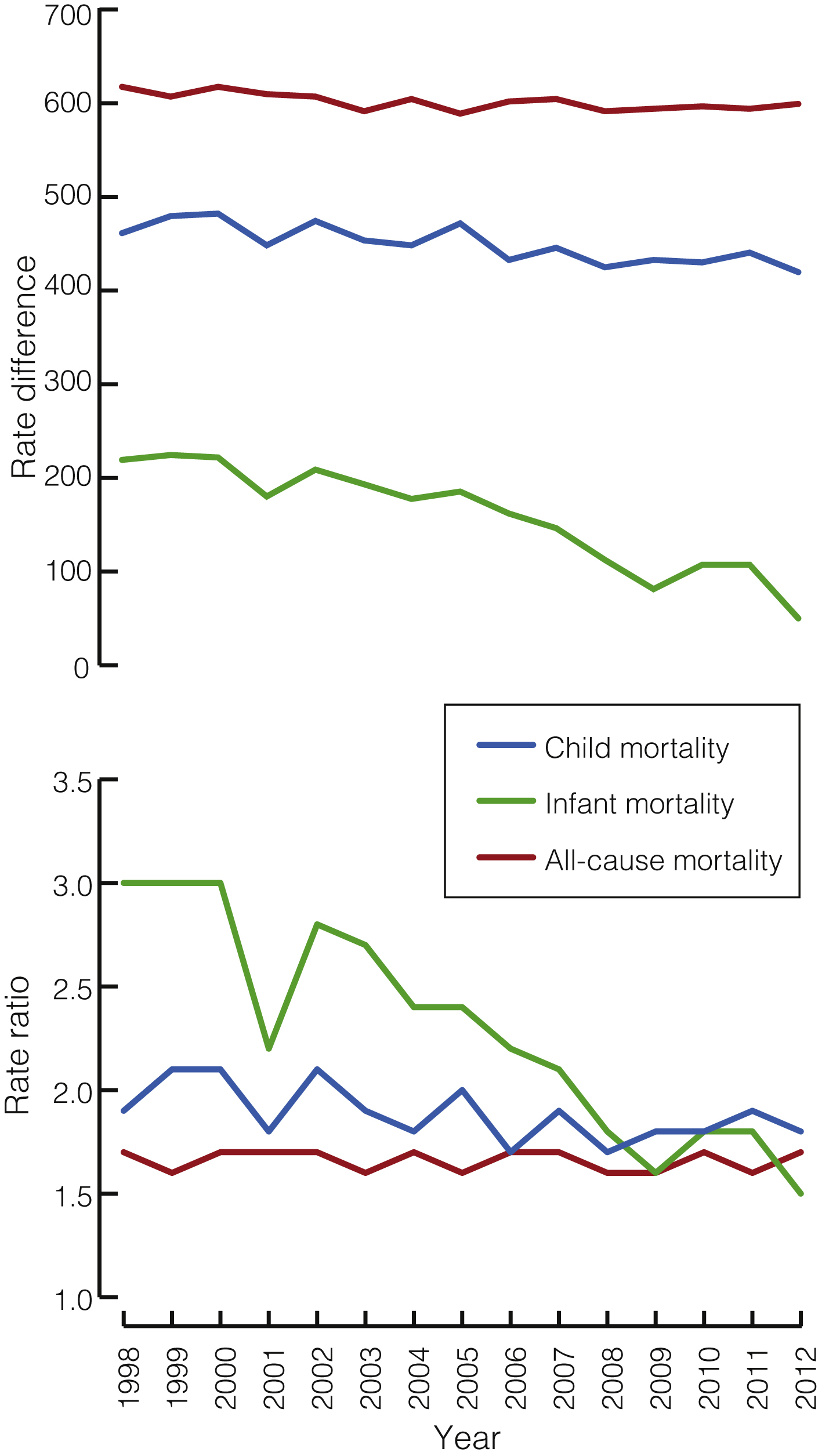

On 28 April 1996, Martin Bryant, a lone gunman using semi-automatic weapons killed 35 people at Port Arthur, Tasmania. In response, the Australian Prime Minister, John Howard, negotiated strict national gun control laws, banning automatic and semi-automatic rifles and shotguns, and introducing uniform stringent firearms licensing, a waiting period, security and storage requirements, sales regulation, and instituting compulsory buybacks of the banned weapons. Licensing required a proven genuine reason, with prohibition or cancellation for violence, apprehended violence or health reasons. The Commonwealth, states and territories implemented the NFA in 1996 and the National Handgun Control Agreement in 2002 with bipartisan support. In their wake, the national firearms stockpile reduced by one-third and public mass shootings have so far ceased. Although total homicides have declined since 1969, stabbings exceed shootings (more lately increasingly [http://www.aic.gov.au/statistics/homicide/weapon.html]), and hanging may later have substituted for gun suicides, rates of total gun deaths, homicides and suicides have at least doubled their rates of decline, suggesting that comprehensive gun control measures were responsible.1,2 A 2010 evaluation found that the reforms were averting at least 200 deaths per year and saving around $500 million annually.3

Community reactions to maintaining public memorial services after 20 years reveal the massacre’s long-term traumatic impacts. The anniversary highlights disparate issues: remembering forgotten (especially Indigenous) massacres; firearm availability; debatable relationships between mental illness, violence, guns and indiscriminate media reporting; and future actions to support rather than erode public health gains.

Following recent mass shootings in the United States, gun lobbyists claim that mentally ill people cause gun violence (http://www.theguardian.com/world/2012/dec/21/nra-full-statement-lapierre-newtown) whereas gun control advocates, including President Barack Obama, have invoked the Australian model.

The relationship of psychosis or serious mental illness and violence has been thoroughly reviewed elsewhere.4–6 Various methodological considerations (eg, institutional versus community samples, definitions of mental illness, temporal relationship of illness and violence) influence conclusions.5 However, from the US Epidemiologic Catchment Area (ECA) Study in 1990 onward, numerous international population studies have confirmed a modest but significant link between mental disorders and community violence (4% 1-year population-attributable risk [PAR] in the ECA study).4 Risks of violence for psychoses are 2–10% PAR compared with the general community, 20% PAR for personality disorders (including antisocial personality disorder), and 25% PAR for substance misuse.4 Odds are higher for homicide; Australian statewide data- and case-linkage studies indicate that people with schizophrenia perpetrated violence five times more often7 but homicide 13 times more often8 than the general community. Some studies show the relationship to be fully mediated by dispositional, situational and disinhibitory factors, including substance misuse;9 others find that substance misuse attenuates, not cancels, the relationship.7,8 Untreated active psychotic symptoms10 and past violence play key roles. Risk for violence in psychosis and schizophrenia may predate active symptoms or result from active illness or treatment. Developmental difficulties, impulsivity and anger, antisocial behaviours, social disadvantage or subculture, and substance use mediate these risks. High risk groups are generally identifiable and most violent acts should be preventable.6

Such studies confirm that most violent individuals do not have mental illness, and that the vast majority of individuals with mental illness are not violent. They are more likely to be victims not perpetrators of violence.11 Media portrayal of violence by people with mental illness reinforces public perception of their dangerousness, further stigmatising and endangering them.4 Almost half of those who die at the hands of US police have some kind of disability.12 Crucially, mental illness is strongly associated with suicide — with PARs ranging from 47% to 74%.4

Individuals who do not have mental illness perpetrate more than 95% of gun homicides.13 Rather than armed civilians reducing crime and homicide, extensive studies show that US gun availability, household gun ownership and diluting gun laws increase firearm homicide14 and suicide.15 In 27 developed countries, gun ownership strongly and independently predicted firearm homicide and suicide, whereas the predictive capacity of mental illness was of borderline significance.16

Although mass murderers who seize media attention often seem to suffer from psychosis, no research clearly verifies that most are psychotic or even suffering from severe mental illness.17 One recent analysis of mass shootings in the US reported that in 11% of cases, prior evidence of concerns about the shooter’s mental health had been brought to medical, legal or educational attention.18 Reports that 43%19 and 56%20 of US mass killers have serious mental illness may be confounded by primary diagnostic reliance on internet, law database and newspaper searches, an apparent dearth of reliable information about psychopathology and authorities’ knowledge of illness, and complications for retrospective analysis of murder–suicide or “suicide by cop”. Of 130 victims of mass gun killings in Australia and New Zealand from 1987 to 2015, 78% were slain by someone without a known history of mental illness, 88% by someone without a history of violent crime, and 56% by someone legally possessing firearms (http://www.gunpolicy.org/documents/5902-alpers-australia-nz-mass-shootings-1987-2015). Thus, the mass killer is frequently until that moment a law-abiding owner of a lawfully held gun.

Mass murder is an almost exclusively male phenomenon that is frequently planned in advance as retribution for perceived wrongs,17 to vindicate, and to potentially overcome hopelessness and invisibility with instant fame and omnipotent destruction. Many have maladaptive (eg, paranoid, sadistic, narcissistic, antisocial) personality configurations.17 Martin Bryant’s trial judge, relying on four forensic psychiatrists’ reports, noted Bryant was not suffering from mental illness but a personality disorder with limited intellectual and empathic capacities (http://www.geniac.net/portarthur/sentence.htm).

Also critical to vindictive or alcohol (or other drug) related gun violence are precipitating and background factors — situations such as domestic conflict and violence, school or work grudges, toxic social networks, and isolation.17 Whether media reporting of other mass murders primes potential perpetrators with instructions and the above incentives21 requires further investigation.

Firearm suicide, overshadowed in public debate but contributing 77% of total gun deaths in Australia in 2014 (http://www.gunpolicy.org/firearms/region/australia#number_of_gun_suicides), is of especial concern. In Queensland, the firearm suicide rate among people with a current licence far exceeded that of those with no licence.22 General rural suicide rates are roughly twice city rates. Farmers may need guns, but safe storage and removal of the weapons at vulnerable periods of life are vital to prevent suicide.

So 20 years later, what are the lessons?

The NFA, which reduced firearm deaths, particularly suicides but also homicides and mass shootings, mirrors similar benefits of comprehensive gun control measures elsewhere.23 However, prevention of firearm injury and mortality intersects with other pressing public and mental health challenges such as domestic violence and suicide, and therefore needs multidisciplinary coordinated efforts.

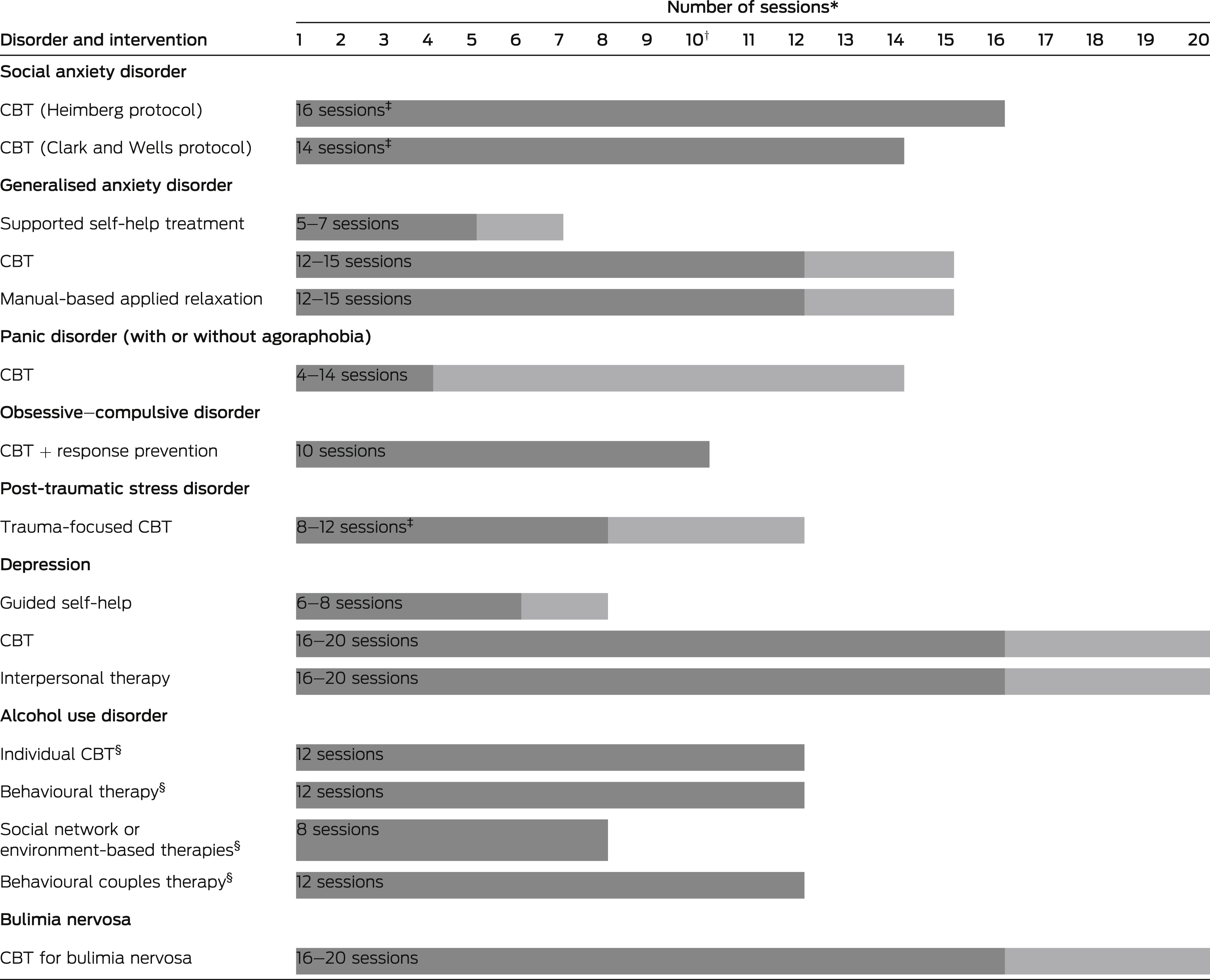

Following recent US gun massacres, there have been calls for better resourcing of mental health services to help identify and respond to those at risk and to regulate firearms access.24 Because people with mental illness are not categorically dangerous, and because sensitivity and specificity problems with screening for violence mean that psychiatrists are no better than laypeople or chance at prediction,4 using strategies such as screening mentally ill populations for violence risk is misguided (not to mention costly, burdensome and infringing rights). However, clinicians have a key role in monitoring and assisting regulation of firearm access, especially for high risk populations (eg, children, adolescents, suicidal people, domestic violence victims and perpetrators, farmers and rural residents, police, and security employees). Their work with legal authorities regarding time-sensitive and situation-specific risks needs further exploration.4 Legal measures include penalising alcohol intake around firearm usage; keeping guns from domestic violence and drink-driving offenders; requiring licensed shooters to surrender guns during periods of vulnerability due to anger, threats and suicidality; and a lower threshold for permanent removal of guns and gun licences. Implications for patient confidentiality, the therapeutic alliance and informed consent, also require examination. As with suicide, responsible media reporting should apply to mass violence.

The national weapons stockpile has now returned to pre-1996 levels (http://www.theconversation.com/if-lawful-firearm-owners-cause-most-gun-deaths-what-can-we-do-48567), highlighting the need to maintain and strengthen the national regulatory regime. Complacency has somewhat eroded the NFA. For example, in New South Wales, the pro-gun lobby succeeded in weakening the regulation of pistol clubs — arguably causing at least one homicide.25 NFA opponents hope to overturn the ban on semi-automatic long arms.

The NFA banned semi-automatic rifles and shotguns, but not semi-automatic handguns (pistols), which are permitted for pistol club members. The logic of stringent restrictions on rapid-fire weapons is equally applicable to handguns, which although currently accounting for few gun deaths, are the concealable weapon of choice for criminals. The medical community has long supported bans for semi-automatic handguns. We need a review, revision and tightening of existing laws and more effective restrictions and controls on possession, import and sales of handguns and other firearms, especially via the internet and by illicit imports.

In the US, the National Rifle Association insists it is not guns that kill but only bad and unhinged people (http://www.theguardian.com/world/2012/dec/21/nra-full-statement-lapierre-newtown). Yet evidence suggests that for some people who are indistinguishable within the general public, including some with interpersonal and personality issues, having easy, legal access to guns is lethal, resulting in avoidable excesses of both domestic and mass killings. Clinicians may offer much to firearm risk management yet must remain ambivalent about targeting those with mental illness for gun intervention if this is not complemented by wider gun control measures.4 The campaign to deflect social concern over firearms availability into a debate about whether people with mental illness histories should access such weapons should be exposed as a calculated appeal to prejudice.

more_vert

more_vert