Clinical record

A 54-year-old man, formerly a smoker, presented with a 6-year history of chronic cough and exertional breathlessness without previous respiratory illnesses. Born in Vietnam, he came to Australia as a refugee at the age of 20 years. A screening chest x-ray was performed on his arrival in Australia; as the patient was not informed about any abnormality, this was assumed to be normal. He commenced work as a labourer; he denied exposure to silica-containing materials and did not participate in activities typically associated with silica exposure (such as jack-hammering) during this period. About 15 years later, the patient started a job manufacturing stone benchtops. He cut, ground, finished and installed the benchtops, using a popular brand of engineered stone comprising > 85% crystalline silica. Occasionally, he made benchtops from granite and marble. During the first 7 years of this work, the patient did not use any respiratory protective equipment, but later used a simple paper mask. Despite some dust extraction facilities in the factory, he reported that the environment was visibly dusty and that dust suppression with water was hardly ever used.

At presentation, chest examination showed scattered fine crackles and bronchial breath sounds bilaterally in the upper zones. Spirometry showed restriction (forced expiratory volume in 1 second [FEV1]/forced vital capacity [FVC], 1.9/2.6 L [73% and 82% predicted, respectively]) and no bronchodilator reversibility; gas transfer was reduced (diffusing capacity of the lungs for carbon monoxide [Dlco], 60% predicted, carbon monoxide transfer coefficient [Kco], 92%).

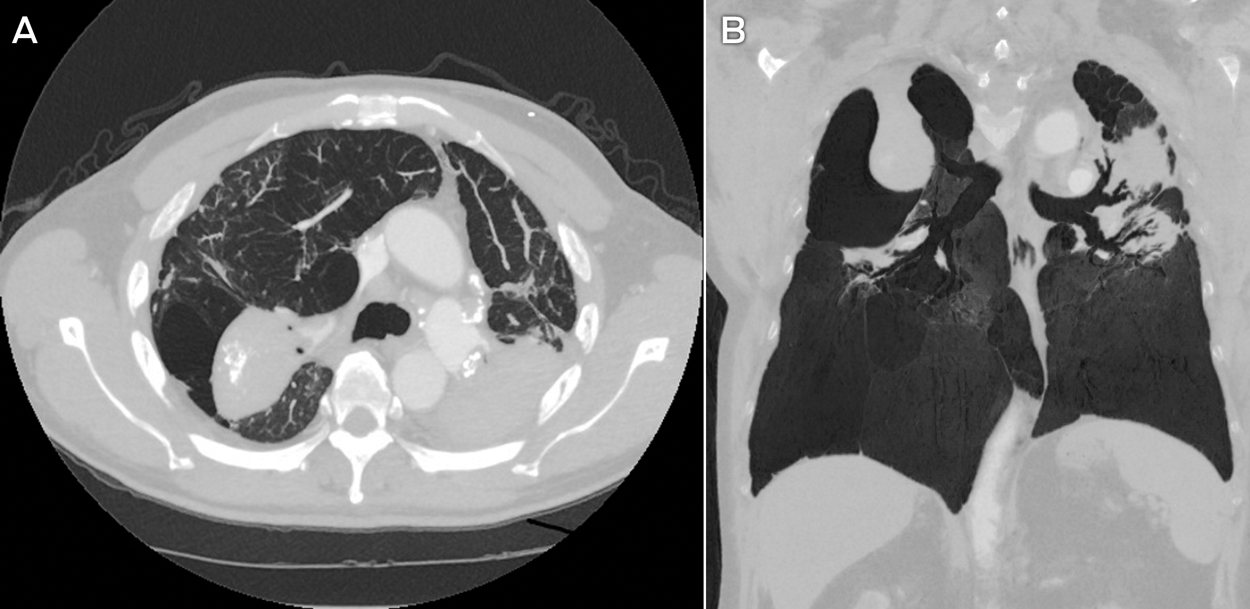

Multiple sputum specimens tested negative for acid-fast bacilli. Levels of inflammatory markers were within reference levels, and the result of a screening test for autoimmunity and vasculitis was negative. A computed tomography (CT) scan of the chest (Box 1) showed confluent bilateral calcified fibrotic masses in the upper zones, with marked volume loss, distortion and perilesional bullae. Occasional small peripheral lung nodules were present, predominantly distributed in the upper zones. There was calcified mediastinal lymphadenopathy.

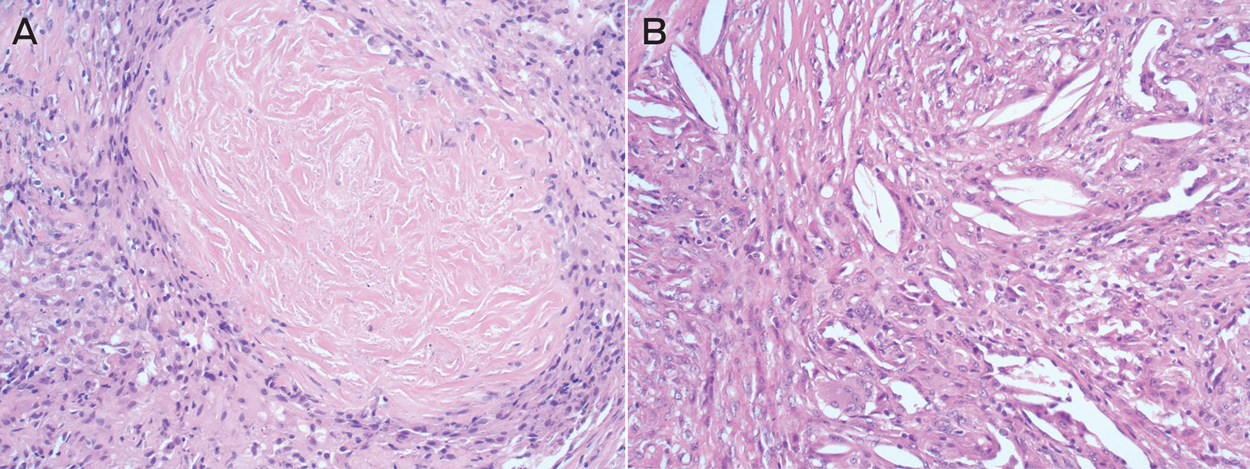

Bronchoscopic washings tested negative for acid-fast bacilli and malignant cells. Positron emission tomography (PET) scanning showed intense uptake in the confluent densities (maximum standardised uptake value, 10.6) and mediastinal lymphadenopathy. CT-guided fine-needle aspiration biopsy was negative for malignant cells. Transbronchial fine-needle aspiration biopsy of lymph nodes using endobronchial ultrasound was non-diagnostic. An open biopsy of the right upper lobe lesions and paratracheal lymph nodes was performed. Histological analysis of the lung sample showed numerous large sclerotic silicotic nodules surrounded by collections of histiocytes (Box 2). Analysis of lymph node sections confirmed prominent nodular silicosis.

Overall, the findings, including PET, were compatible with a diagnosis of complicated silicosis with progressive massive fibrosis. The patient continued to experience worsening breathlessness, despite treatment with bronchodilators and inhaled corticosteroids. He subsequently developed bilateral pneumothoraces, requiring temporary intercostal drain insertion, and is now listed for lung transplantation.

Silicosis refers to a spectrum of progressive and debilitating occupational lung diseases caused by the inhalation of free crystalline silica. Once established, there is no effective treatment. Prevention is therefore paramount. Exposure to silica has been unequivocally associated with an increased risk of lung cancer, as well as an increased frequency of tuberculosis and possibly also autoimmune disease. Implementation of appropriate workplace standards to minimise exposure is crucial to reduce incident and severe cases of silicosis.

Silicon dioxide (silica) is the most abundant mineral on Earth and is present in almost all types of rock, sand, clay and gravel. The most common crystalline forms of silica are quartz, cristobalite and tridymite. Silica exposure may occur in many work settings. Despite a global downward trend, new outbreaks of silicosis have recently been reported, with life-threatening silicosis occurring after exposure to a relatively new type of engineered stone product used for kitchen and bathroom benchtops.1,2 These products (known as “artificial quartz conglomerate” and “artificial stone”), which contain a high content of free crystalline silica (70–90%), are increasingly used in preference to their marble and granite counterparts because of their low cost, improved durability and hardness.

Risk of exposure to high levels of crystalline silica from engineered stone is present at all levels of this industry, from manufacturing (stone cutting, shaping and finishing) to assembly and installation.3 In a recent study, 25 ornamental stone workers who had been employed in dry-cutting a synthetic stone product developed advanced silicosis.1 In another report, silicosis was diagnosed in 46 men working in the manufacture of artificial stone for kitchen benchtops.2

Following these reports, an alert issued in the United States highlighted potentially dangerous levels of silica exposure associated with suboptimal practices in the artificial stone industry.4 Further calls to action have come from Europe, with a report from Tuscany citing seven cases of silicosis in workers exposed to crystalline silica during benchtop manufacturing.5 In almost all reported cases, there was little adherence to basic protection measures, such as provision of appropriate ventilation systems and use of personal protective equipment.

The Safe Work Australia workplace exposure standard for respirable crystalline silica (time-weighted average) is 0.1 mg/m3, which is designed to prevent the occurrence of silicosis.6 Our case reaffirms the need for vigorous enforcement of dust reduction regulations, particularly in the growing industry of engineered stone products. Benchtop stonemasonry is a potentially dangerous occupation, and medical practitioners should have a heightened awareness of this newly described occupational hazard.

Lessons from practice

-

Silicosis is a disabling but entirely preventable occupational lung disease caused by exposure to inhaled free crystalline silica.

-

Recent outbreaks of silicosis have been associated with the manufacture of relatively new engineered stone products that are used for kitchen and bathroom benchtops.

-

Medical practitioners should be aware that cutting and installing these engineered artificial stone products can be a hazardous occupational exposure.

-

Appropriate dust suppression practices and the use of respiratory protective equipment should be reinforced to prevent silica-related diseases.

Box 1 –

Axial (A) and coronal (B) computed tomography scans of the patient’s lungs

Box 2 –

Typical features of silicosis on lung histopathology slides

more_vert

more_vert