In low-income and middle-income countries, meeting inpatient and outpatient rehabilitation needs of stroke survivors with insufficient staff and facility resources is especially challenging. Family-delivered rehabilitation services might be an innovative way to augment intensity of practice.1 The ATTEND Collaborative Group’s ATTEND trial,2 published in The Lancet, is to our knowledge the first appropriately powered trial to investigate the effect of family-delivered, home-based rehabilitation intervention for patients with stroke in a low-middle-income country.

Preference: Rehabilitation

1024

Outstanding doctor from outstanding Israeli hospital visits Down Under

Internationally renowned Israeli doctor Nitza Heiman Newman is currently visiting Australia representing the Soroka Medical Centre, the only major medical centre in the entire Negev.

It is one of the largest and most advanced hospitals in Israel, serving a population of more than one million people, including 400,000 children, in a region that accounts for more than 60 per cent of the country’s total land a

Soroka also serves as a teaching hospital of the Ben-Gurion University Medical School.

But what makes Soroka even more unique in the region is that in a nation often embroiled in conflict, it caters for everyone.

“We treat people by the severity of the medical problems they have, not by any religion or culture,” Dr Newman said.

“You can see in our wards, in the same room, Israelis, Jews, Arabs, Bedouin and more.

“And you can see the changes of the people in those wards. It can sometimes start out with – I wouldn’t say with tension, but maybe with some suspicion amongst the patients and those who visit them. But within 24 hours they are getting along better and visitors are often bringing along cakes for everyone in the room.”

Another thing making Soroka a standout facility is the way it is prepared for trauma. In a war zone, this is a necessity.

“What we see a lot of unfortunately is military trauma in our area. The last time there was a serious breakout two years ago our helipad was very, very busy and we were treating a constant flow of injured soldiers and civilians,” Dr Newman said.

“We are one of the biggest medical centres in Israel and definitely as a trauma centre. But we are also a general hospital with more than a thousand beds.

“We do everything, including transplants. Our specialty is genetics and we also have the biggest delivery room in the country – delivering 55 new babies every day.”

Dr Newman says Soroka is an example to the world, which is part of her reason for being in Australia.

She is speaking at forums about the medical centre and also about the United Israel Appeal program called Professions for Life, which assists new immigrants to Israel to re-certify in their chosen professions.

“If you make the transition easier for new immigrants you make their lives easier and they integrate faster,” she said.

“It makes life more enjoyable for them and for those who absorb them into the community.”

Born in Israel, the only child of Holocaust survivors, Dr Newman served in a range of positions in the Israel Defense Forces, including as an officer in the Golani Brigade. Her last army position was as a company commander in a female officers’ course.

She took a year off from medicine to direct a school in Be’er Sheva for gifted children, before taking a residency in pediatric surgery at Soroka Medical Center in Be’er Sheva.

She then did a year-long fellowship at Great Ormond Street Hospital in London in the field of pediatric oncology surgery, a field that she developed at the hospital.

Since 2005, Dr Newman has been responsible for the Dr. Gabi and Eng. Max Lichtenberg scientific program in surgery for outstanding staff at Ben-Gurion University.

From 2009-2013, she was a member of the Be’er Sheva city council and responsible for the health and environment portfolio.

Since 2010 she has been the deputy hospital director, in charge of medical personnel, children’s division, maternity division, gynecology, psychiatry and now rehabilitation as well.

Chris Johnson

Ley ‘expects’ health funds to pass on prostheses price cuts

Health Minister Sussan Ley has raised expectations of a slowdown in the growth of private health insurance premiums after announcing a multimillion dollar cut in the cost of common medical implants.

As insurers finalise their proposed premium increases for 2017, Ms Ley has approved changes in the pricing of 2440 prostheses including pacemakers, intraocular lens’ and artificial hips and knees that she said would save health funds $86 million in the first year and $394 million over five years.

The Minister is pressuring insurers to pass on the savings to their members in lower premiums.

“I expect that every dollar of the $86 million finds its way to the bottom line to reduce the cost of next year’s premium,” she told reporters. “I expect if insurers take $86 million out of the cost they pay the hospital that will immediately transfer to lower premium increases for patients and consumers.”

But the Minister refused to specify by how much she expected premiums to fall, and demurred when asked to detail what processes were in place to ensure insurers passed the cuts on to policyholders.

Her reluctance was seized upon by Labor. Shadow Health Minister Catherine King said that while steps to improve health insurance affordability were welcome, “there is no guarantee whatsoever that these cuts will be passed on to consumers”.

But in evidence to a Senate Estimates hearing, senior Health Department officials said the move would put downward pressure on premiums and expected it would result in “a lesser increase than there would otherwise have been”.

Earlier this year Ms Ley initiated a review of the way the Government sets the price of prostheses amid complaints by insurers that they were being charged grossly inflated prices compared with those billed to public hospitals.

Health funds claimed that up to $800 million could be saved by bringing prostheses costs in private hospitals in line with those paid in the public sector. For example, a public hospital in WA is charged $1200 for a coronary stent that costs $3450 in the private system.

The claimed savings have been disputed by private hospitals and medical device manufacturers, and the Medical Technology Association of Australia told The Australian the cuts announced by the Minister would result in job losses, increased out-of-pocket expenses for patients and cost shifting to other parts of the private health sector.

Ms Ley, under pressure over mounting patient disaffection with the relentless rise of insurance premiums – which have been growing by around 6 per cent a year – has prioritised reform of the Prostheses List as a way to rein in the cost of private health cover and slow the drift of policyholders to cheaper but much less comprehensive policies riddled with multiple exclusions.

In February, she appointed Professor Lloyd Sansom to head a working group looking at medical device pricing, including the operation of the Prostheses List, which was created in 1985 to set out the maximum benefit insurers should pay for medical implants and devices.

Since 2001, there have been a number of regulatory reforms that have resulted in a significant increase in prices.

The Australian has reported that the cuts announced by the Minister are based on advice from the Sansom review, which highlighted how the regulated prices of cardiac devices, intraocular lens systems, hips and knees were “significantly higher, in many cases, than market prices based on available domestic and international data”.

“These categories are considered appropriate for initial consideration for benefit reduction because they have large volumes and benefits paid, with relatively high levels of competition among prostheses sponsors,” it said.

The AMA said it supported a “robust and transparent process” for prosthetic pricing, and backed the use of price referencing in review charges on Prostheses List.

But it urged the Government to make sure that any changes did not have the unintended consequence of reducing the range of prostheses available to privately insured patients.

The Association said it would be vigilant in ensuring that Government reforms and health fund initiatives did not encroach on the freedom of medical practitioners to make decisions in the best interests of their patients.

It called for Prostheses List reforms that emphasised the importance of clinician choice, reduce prices and were devised taking into account possible implications for the cost of rehabilitation.

Adrian Rollins

[Comment] The Paralympics—superhumans and mere mortals

This month has seen the amazing achievements of the Rio 2016 Paralympic Games, a movement that can be traced back to Sir Ludwig Guttmann’s early attempts at promoting rehabilitation for disabled people and the Stoke Mandeville games first held in 1948. This is a good moment to reflect not only on the role of sport for people with disabilities, but also on barriers to them accessing leisure facilities.

Royal Commission must shine light on NT juvenile justice and health

The AMA has thrown its support behind the Federal Government’s decision to establish a Royal Commission into the mistreatment and abuse of young people being held in detention in the Northern Territory.

AMA President Dr Michael Gannon said shocking images and revelations broadcast by the ABC’s Four Corners program had sent shockwaves through the community, and reinforced warnings made by the AMA over many years about the treatment of people, particularly children, incarcerated in the NT.

“The cruelty, violence, and victimisation experienced by these young people will have impacts on their mental and physical health for the rest of their lives,” Dr Gannon said.

“The unacceptable abuse that took place at the Don Dale Detention Centre is clearly indicative of broader problems in the detention and prison systems in the Northern Territory. The AMA, at both the Federal and Territory level, has raised concerns over many years based on reports from doctors and other health professionals, including AMA members, about the poor condition and treatment of people in detention in the Territory, especially children – very often Indigenous teenagers.”

Rates of incarceration among Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people are startlingly high – they comprise 28 per cent of all prisoners, and are 13 times more likely to be locked up than other Australians.

Young Indigenous people are even more likely to be imprisoned – they make up half of all children aged between 10 and 17 years held in detention, and are 17 times more likely to be under “youth justice supervision” than children of the same age in the broader community.

Dr Gannon said the Royal Commission would “put a spotlight” on juvenile justice and the health issues that were often involved in getting young people locked up, and called for “brave and creative” thinking about alternatives to imprisonment.

“Health issues – notably mental health conditions, alcohol and drug use, substance abuse disorders, cognitive disabilities – are among the most significant drivers of incarceration. We must also look at the intergenerational effects of incarceration,” the AMA President said.

The revelations of shocking abuse at the Don Dale Centre have also focused attention on police practices that are seen to be contributing to high rates of imprisonment among Indigenous children, particularly the NT’s ‘paperless arrest’ powers that allow police to detain people for up to four hours for minor offences.

“There must be a community debate about alternatives to incarceration, and serious investigation into alternative methods of rehabilitation for young offenders,” Dr Gannon said. “This will require considering new ideas, and brave and creative thinking.”

The health impacts of high rates of Indigenous imprisonment were highlighted by the AMA in its Indigenous Health Report Card 2015 – Treating the high rates of imprisonment of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples as a symptom of the health gap: an integrated approach to both released last year.

“The rate of imprisonment of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people is rising dramatically, and is an issue that demands immediate action,” the Report Card said.

The AMA has called for the Federal Government to set a national target to close the gap in imprisonment rates between Indigenous people and the rest of the community, with children and young people the immediate priority.

Adrian Rollins

HIP4Hips (High Intensity Physiotherapy for Hip fractures in the acute hospital setting): a randomised controlled trial

The known Early mobilisation and daily physiotherapy after hip fracture fixation are recommended by guidelines, but there is no evidence that guides the intensity of acute hospital physiotherapy for this patient population.

The new Intensive acute hospital physiotherapy following an isolated hip fracture reduced hospital length of stay by more than 10 days without increasing complication or re-admission rates.

The implications We have provided evidence-based support for intensive physiotherapy programs in the acute hospital setting after hip fracture. Our findings may have significant practical implications, given the large number of inpatient beds occupied by this patient group.

Rising rates of hip fracture in our ageing population and the consequently increasing costs of care are significant problems for the hospital system and the community.1 In Australia, 17 000 hip fractures in people aged 65 years or more incur direct hospital costs of $579 million each year,2 and it is projected that the annual number of hip fractures will rise to 60 000 by 2051.1 Costs continue to accrue after patients leave hospital, with about 25% requiring full-time nursing home care3,4 and 50% of previously independent patients needing a gait aid or long term help with routine activities.3

Many strategies have been tried and guidelines developed for optimising the management of this population, including reducing the time to surgery and improving analgesia.5 Several rehabilitation strategies have also been investigated, including early assisted ambulation (within 48 hours of surgery)6 and multidisciplinary programs.7

There are no recommendations about the intensity of physiotherapy during the acute post-operative phase following hip fracture fixation. One cohort study found that increased intensity of acute hospital physiotherapy was associated with a greater likelihood of discharge home.8 Intensive physiotherapy for trauma patients was recently found to be safe, leading to more rapid improvements in mobility.9 Whether these findings can be extrapolated to patients with fractured hips or if early, intensive intervention has longer term benefits are, however, unknown.

The aim of our study was to investigate the effect of providing an intensive physiotherapy program for patients aged 65 years or more with isolated hip fractures.

Methods

Design and ethics approval

This was a single-centre, prospective randomised controlled trial at The Alfred, a level 1 trauma centre in Melbourne. Approval was granted by the Alfred Health Human Research and Ethics Committee (reference, 32/14). The study was registered with the Clinical Trials Registry in March 2014 (https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT02088437).

Subjects

Between March 2014 and January 2015, all patients admitted to The Alfred with isolated hip fractures were screened for study inclusion. If patients were unable to provide consent, it was requested from the person responsible for their medical decisions. Patients were included if they were at least 65 years old, had been admitted with an isolated subcapital or intertrochanteric hip fracture, and were treated by internal fixation or hemiarthroplasty. Patients were excluded if the fracture was subtrochanteric or pathological, and if post-operative orders required the patient to be non-weight-bearing on the operated hip. Patients who were unable to move independently or who needed a gait aid prior to admission, and those admitted from nursing homes were also excluded.

Participants were randomly assigned by computer program to one of two groups: usual care (the control group), in which they received one daily treatment session of 30 minutes; or intensive physiotherapy (the intervention group), in which they received two additional daily treatment sessions of about 30 minutes each. Allocation was concealed by using opaque envelopes.

Physiotherapy

The usual care physiotherapist was blinded to the allocation, and treated all patients in the morning. The intervention group physiotherapist and allied health assistant provided physiotherapy during the afternoon; this was not documented in the patient’s medical record, maintaining the blinding of the usual care therapist and treating team.

Usual physiotherapy care

Patients in both groups received daily physiotherapy according to usual practice in the trauma centre, 7 days per week. Treatment was individualised and involved bed-based limb exercises (eg, strength exercises, such as knee extension, and active hip exercises) and gait re-training. The goal was early, independent transfer and mobility, with the objective of discharge directly home or to fast stream rehabilitation.

Intervention group

Patients in the intervention group received two additional daily sessions, 7 days per week. One session, delivered by an allied health assistant, practised the achievements of the morning session. An additional session, delivered by a physiotherapist, aimed to improve the functional advances achieved during the earlier physiotherapy session; eg, increased independence, progression of gait aid (eg, from frame to crutches), and increasing the distance walked.

Discharge criteria

A physician blinded to group allocation reviewed all patients, and determined medical stability and the need for inpatient rehabilitation. Participants were discharged home once they were medically stable, were deemed physically ready to return home by the blinded physiotherapist, and had been cleared by the multidisciplinary team. Physical readiness was defined as independence in bed and chair transfers, walking with a gait aid, and negotiation of any stairs required by the patient to safely enter or leave their home.9,10 If patients were unable to achieve these criteria before medical stability was achieved, they were transferred to an inpatient rehabilitation facility, per hospital protocol.

Data collection

Demographic data collected included sex, age, mechanism of injury, pre-morbid mobility level, social circumstances (residence, support at home) and home set-up (distance and steps to house entrance). Cognitive function was assessed by the physician with the Mini-Mental Status Examination, with scores ranging from 0 to 30 points: patients scoring 26–30 have no functional cognitive impairments, those scoring 20–25 display mild cognitive impairments, and those scoring less than 20 points having moderate to severe cognitive impairments and usually cannot live independently.11 Operative data, including fracture type (subcapital, intertrochanteric), operative time, post-operative weight-bearing status, and American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) score,12 were also collected. The ASA score provides a six-category physical status classification system, ranging from the normal healthy person (1) to brain-dead (6).

Outcome data were collected on post-operative Day 5, at discharge, and at 6 months. The primary outcome, the modified Iowa Level of Assistance (mILOA) score, was measured by a blinded assessor on post-operative Day 5 (or on the day of discharge, if this occurred earlier). The ILOA scale was originally designed for assessing patients with lower limb arthroplasty,13 and was later modified for patients who had fractured a hip.6 The mILOA is a functional score with six domains, including bed and chair transfer, ambulation, ascending/descending one step, and gait aid used. The score ranges from 0 (independent in all activities without a gait aid) to 36 (unable to attempt any of the activities). The scale has been validated in an acute hospital population14 and was found to be responsive in an earlier physiotherapy trial.9 Secondary outcome measures included a Timed Up and Go (TUG) test,15 administered by a blinded assessor to patients who were mobilising without assistance at Day 5 (a prerequisite for this test). Data on acute hospital length of stay (LOS), inpatient rehabilitation LOS and combined hospital LOS, inpatient complications, and re-admissions were also collected. Time to physical readiness for discharge, based on the criteria for discharge home applied by an elective joint replacement early discharge program,10 was also recorded. Other data included discharge destination from the acute hospital (home; slow or fast stream rehabilitation) and pain scores before and after physiotherapy. The amount of pain relief medication taken during the first 72 hours after surgery was recorded as the opioid equivalence score.16 Six-month outcome information was derived from routinely collected data in the Victorian Orthopaedic Trauma Outcomes Registry (VOTOR), including discharge destination, and Short Form 12 Health Survey (SF-12), Glasgow Outcome Scale (extended) (GOS-E), and EuroQol five dimensions health state questionnaire (EQ-5D) scores.17 When the patient was unable to provide a response to the EQ-5D, proxy responses were substituted.18

Statistical analysis

Ninety-two patients were required to detect a genuine difference of seven units on the mILOA scale at Day 5 (80% power, α = 0.05 [two-sided]),13 assuming that the standard deviation of the response variable was 11 (based on data reported for this outcome in a previous study19). This sample size calculation allowed for an anticipated drop-out rate of 15%.

Analyses were performed in Stata 12.0 (StataCorp). Data are presented as means and standard deviations, or as medians and interquartile ranges if the data were not normally distributed. Differences between groups at baseline were assessed with independent samples t tests (continuous data) or χ2 tests (categorical data). Data for the outcomes LOS, time to walk, time to sit out of bed, sum of hours, occasions of service, and physical readiness for discharge were not normally distributed, so these variables were natural log-transformed. Differences in outcome variables between treatment groups were compared by univariate analysis of variance (continuous variables) or with χ2 tests (categorical variables). The GOS-E data were dichotomised into scores of ≥ 7 (“good recovery”) or < 7 (“less than good recovery”)20 and analysed in χ2 tests. mILOA scores and combined LOS were assessed by linear regression; all potential confounders related to these outcomes in the univariate analysis (P < 0.2) were included in this analysis.

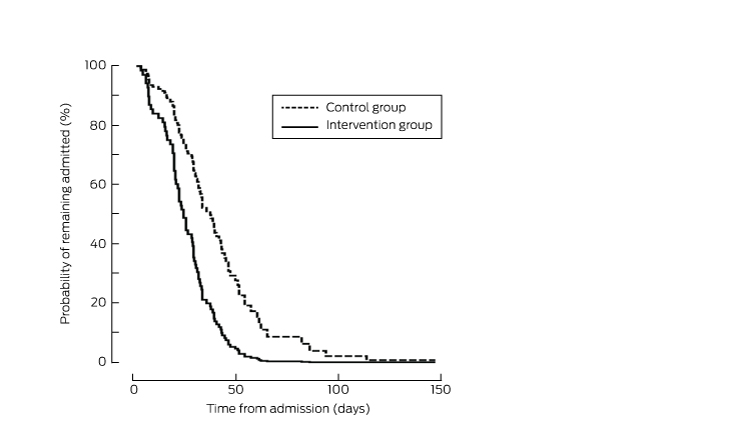

The effect of group allocation on time to discharge (as measured by combined LOS) was evaluated by Cox proportional hazard regression. Corresponding Kaplan–Meier curves were constructed and compared in log-rank tests.

Results

Between March 2014 and January 2015, 170 patients were screened; 68 were excluded, and 92 patients were recruited (46 allocated to each group). One control group patient was unable to participate in physiotherapy during the first 7 days because of a post-operative complication (dislocation prior to the initial physiotherapy intervention). No patients withdrew from the study, and Day 5 outcome measures were collected for all patients. The trial complied fully with CONSORT guidelines (http://www.consort-statement.org/); the CONSORT flow diagram for participation is included in the Appendix.

Demographic data for the two groups are summarised in Box 1. The groups were well matched for age, fracture type, and length of surgery, as well as for pre-operative mILOA and ASA scores. There was a significant difference between the groups for anaesthetic type, with patients in the intervention group more likely to have had a general anaesthetic. The patients in the intervention group were also less likely to have support at home, and there was a trend towards a greater proportion of women in this group.

There was no difference between the groups in the primary outcome measure, mILOA score on post-operative Day 5, with a mean difference of 2.7 points (mean scores: control group, 19.2 [SD, 8.4]; intervention group, 16.5 [SD, 9.4]; P = 0.10) (Box 2). However, after controlling for potential confounding factors (sex, anaesthetic type, carer at home, stairs at home), the Day 5 mILOA score was lower (better) in the intervention group (P = 0.04, Box 3). Hospital LOS (acute and inpatient rehabilitation) was 10.6 days shorter in the intervention group (median LOS: control, 35.0 days [IQR, 19.0–49.8]; intervention, 24.4 days [IQR, 16.4–31.6]; P = 0.01). This difference persisted in a linear regression that controlled for possible confounding factors (Box 4).

A Cox proportional hazards model that controlled for sex, anaesthetic type, presence of a carer at home, and presence of stairs at home found that the intervention conferred a benefit in terms of earlier discharge from hospital (hazard ratio, 2.30; 95% CI, 1.40–3.78; P < 0.001) (Box 5).

There was no difference between the two trial groups in mean pain or opioid equivalent scores over the first 3 post-operative days (Box 6), nor were there differences in the rates of complications or re-admission, or in longer term patient-reported outcomes (Box 2).

Discussion

We found that an intensive physiotherapy program beginning on the first day after surgery for an isolated hip fracture in patients over 65 years of age is safe and effective. There was no statistically significant difference between control and intervention groups in the primary outcome of functional mobility on post-operative Day 5, but hospital LOS was significantly lower for the intensive physiotherapy group. There were also no differences between groups with respect to pain levels or opioid pain relief requirements. These findings further support the current guidelines, which recommend physiotherapy after a hip fracture to facilitate early assisted ambulation.

After controlling for relevant confounders, our primary outcome, mILOA score, was significantly better in the intervention group at Day 5 (Box 3). Functional mobility at discharge is a major determinant of mortality,21 and whether this improved mobility affects longer term outcomes should be investigated. We powered our study to detect a 7-point difference, as this has been reported as the smallest difference in mILOA score of clinical importance.13 The between-group difference in favour of the intervention group did not reach this threshold, so the difference we found may not be clinically significant. Unfortunately, we only collected data on the primary outcome measure at one post-operative time point; Day 5 may be too early to detect a substantial difference in functional mobility in this patient group, and assessing function at longer time intervals would be desirable.

The economic burden of hip fractures is great;3,22 they account for 14% of all osteoporotic fractures, but for 72% of costs, which are largely associated with inpatient care.22 We found that hospital LOS (a secondary outcome measure) was shorter in the intervention group, with a 10-day reduction across acute and subacute care, reflected by a similar improvement in the time to physical readiness for discharge. This was achieved without an increase in rates of in-hospital complications or re-admissions, and without affecting 6-month outcomes. The difference in LOS is still evident well into the rehabilitation period (Box 5). This may represent an important cost saving, given the large numbers of patients requiring management in hospital systems worldwide, and the high costs associated with their care.

The strengths of our study were its robust design, the randomisation protocols, and the blinding of both the usual care physiotherapist and the outcome assessor to trial group allocation. No patient was lost to follow-up during the in-hospital phase of data collection, and 6-month outcome scores could be collected for more than 85% of participants.

The limitations of our study include the relatively small numbers in each trial group (the result of the single institution trial design) and the short duration of the intervention (limited to acute hospital stay). Although our cohort was randomised, there were minor differences between the groups at baseline; more patients in the intervention group had received a general anaesthetic, and fewer had support at home. These differences highlight the importance of our findings, as previous studies have shown that patients who receive a general anaesthetic have an increased rate of post-operative complications,23 and those without support at home are more likely to require assistance after discharge and to be discharged to a higher level of care.24 Further, most patients were at home prior to admission, limiting the generalisability of our findings. We have not provided a robust cost analysis of the project or detailed information regarding resource allocation, although the financial benefit of reducing hospital LOS is clear.

Conclusion

We found that an intensive physiotherapy program for patients in the acute care setting after an isolated hip fracture can reduce hospital LOS by more than 10 days without increasing the rates of complications or re-admissions. Our study provides support for providing intensive physiotherapy programs for those with hip fractures, and this should be considered in future care guidelines.

Box 1 –

Demographic data for the usual care (control) and intensive physiotherapy (intervention) groups

|

Characteristic |

Usual care |

Intensive physiotherapy |

P |

||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||

|

Number of patients |

46 |

46 |

|

||||||||||||

|

Age (years), mean (SD) |

81.3 (9.0) |

81.3 (7.5) |

1.00 |

||||||||||||

|

Sex |

|

|

|

||||||||||||

|

Men |

21 (46%) |

12 (26%) |

0.05 |

||||||||||||

|

Women |

25 (54%) |

34 (74%) |

|

||||||||||||

|

Fracture type |

|

|

|

||||||||||||

|

Subcapital |

30 (65%) |

25 (54%) |

0.29 |

||||||||||||

|

Intertrochanteric |

16 (35%) |

21 (46%) |

|

||||||||||||

|

Pre-operative modified Iowa Level of Assistance score, mean (SD) |

1.74 (2.80) |

1.39 (2.56) |

0.54 |

||||||||||||

|

Pre-operative American Society of Anesthesiologists score |

|

|

|

||||||||||||

|

1 |

4 (9%) |

1 (2%) |

0.36 |

||||||||||||

|

2 |

10 (22%) |

15 (33%) |

|

||||||||||||

|

≥ 3 |

32 (70%) |

30 (65%) |

|

||||||||||||

|

Mini-Mental Status Examination score* |

|

|

|

||||||||||||

|

26–30 |

5 (14%) |

6 (17%) |

0.15 |

||||||||||||

|

20–25 |

16 (44%) |

8 (23%) |

|

||||||||||||

|

< 20 |

15 (43%) |

21 (60%) |

|

||||||||||||

|

Residence |

|

|

|

||||||||||||

|

Home |

44 (96%) |

42 (91%) |

0.24 |

||||||||||||

|

Retirement village |

1 (2%) |

0 |

|

||||||||||||

|

Low level care |

1 (2%) |

4 (9%) |

|

||||||||||||

|

Carer at home* |

|

|

|

||||||||||||

|

Yes |

24 (53%) |

14 (31%) |

0.03 |

||||||||||||

|

No |

21 (47%) |

31 (69%) |

|

||||||||||||

|

Stairs at home |

|

|

|

||||||||||||

|

Yes |

36 (78%) |

29 (63%) |

0.11 |

||||||||||||

|

No |

10 (22%) |

17 (37%) |

|

||||||||||||

|

Health care funding* |

|

|

|

||||||||||||

|

Private |

8 (21%) |

13 (31%) |

0.36 |

||||||||||||

|

Medicare |

30 (79%) |

28 (67%) |

|

||||||||||||

|

Transport Accident Commission |

0 |

1 (2%) |

|

||||||||||||

|

Anaesthetic type |

|

|

|

||||||||||||

|

General |

34 (74%) |

42 (91%) |

0.03 |

||||||||||||

|

Spinal |

12 (26%) |

4 (9%) |

|

||||||||||||

|

Length of surgery (minutes), median (IQR) |

82 (62–101) |

74.5 (55–101) |

0.96 |

||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||

|

* Missing data mean that numbers do not add to column total. |

|||||||||||||||

Box 2 –

Outcomes for the usual care (control) and intensive physiotherapy (intervention) groups

|

Outcome |

Usual care |

Intensive physiotherapy |

P |

||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||

|

Number of patients |

46 |

46 |

|

||||||||||||

|

Modified Iowa Level of Assistance (mILOA) score, mean (SD) |

19.2 (8.4) |

16.5 (9.4) |

0.15 |

||||||||||||

|

Timed Up and Go conducted |

16 (35%) |

24 (52%) |

0.09 |

||||||||||||

|

Timed Up and Go (seconds), median (IQR) |

69 (51.5–96.5) |

47 (31–89) |

0.08 |

||||||||||||

|

Acute hospital length of stay (days), median (IQR) |

7.4 (5.4–8.8) |

6.0 (4.6–7.2) |

0.08 |

||||||||||||

|

Inpatient rehabilitation length of stay (days), median (IQR) |

29.9 (15.9–42.9) |

21.0 (13.8–26.8) |

0.06 |

||||||||||||

|

Combined hospital length of stay (days), median (IQR) |

35.0 (19.0–49.8) |

24.4 (16.4–31.6) |

0.01 |

||||||||||||

|

Time to physical readiness for discharge (days), median (IQR) |

27.7 (14.0–37.6) |

16.3 (5.8–25.6) |

0.02 |

||||||||||||

|

Physiotherapy occasions of service, median (IQR) |

5 (3–6) |

10.5 (7–14) |

< 0.001 |

||||||||||||

|

Time spent in physiotherapy (hours), median (IQR) |

115 (70–160) |

248.5 (145–290) |

< 0.001 |

||||||||||||

|

Time to sit on bed (days), median (IQR) |

1.02 (0.9–1.8) |

1.0 (0.9–1.5) |

0.43 |

||||||||||||

|

Time to walk 3 metres (days), median (IQR) |

1.95 (1.0–4.6) |

1.93 (1.1–3.0) |

0.19 |

||||||||||||

|

Discharge destination from acute hospital |

|

|

0.31 |

||||||||||||

|

Home |

5 (11%) |

10 (22%) |

|

||||||||||||

|

Fast stream rehabilitation |

11 (24%) |

12 (26%) |

|

||||||||||||

|

Slow stream rehabilitation |

30 (65%) |

24 (52%) |

|

||||||||||||

|

Final discharge destination |

|

|

0.86 |

||||||||||||

|

Home |

33 (72%) |

36 (78%) |

|

||||||||||||

|

Low level care |

7 (15%) |

6 (13%) |

|

||||||||||||

|

High level care |

6 (13%) |

4 (9%) |

|

||||||||||||

|

In-hospital complications |

|

|

|

||||||||||||

|

Hip dislocation |

1 (2%) |

0 |

0.32 |

||||||||||||

|

Troponin levels > 26 ng/L |

3 (7%) |

5 (11%) |

0.46 |

||||||||||||

|

Anaemia requiring transfusion |

9 (20%) |

11 (24%) |

0.61 |

||||||||||||

|

Acute kidney injury |

8 (17%) |

4 (9%) |

0.22 |

||||||||||||

|

Re-admission within 6 months |

|

|

0.25 |

||||||||||||

|

Hip-related |

4 (9%) |

2 (4%) |

|

||||||||||||

|

Not hip-related |

12 (26%) |

3 (7%) |

|

||||||||||||

|

6-month Glasgow Outcome Scale (extended) (GOS-E) score* |

|

|

0.10 |

||||||||||||

|

< 7 |

26 |

17 |

|

||||||||||||

|

≥ 7 |

15 |

21 |

|

||||||||||||

|

6-month EuroQol (5 dimensions) (EQ-5D), mean score (SD)† |

63.1 (22.3) |

70 (16.7) |

0.15 |

||||||||||||

|

6-month SF-12, mental components, mean score (SD)‡ |

59.3 (3.7) |

56.8 (7.0) |

0.27 |

||||||||||||

|

6-month SF-12, physical components, mean score (SD)‡ |

44.3 (11.8) |

41.7 (11.9) |

0.56 |

||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||

|

SF-12 = Short Form 12 health survey. * n = 41 (control group), n = 38 (intervention group). † n = 36 (control group), n = 36 (intervention group). ‡ n = 12 (control group), n = 18 (intervention group). |

|||||||||||||||

Box 3 –

Linear regression analysis of the relationship between modified Iowa Level of Assistance (mILOA) score and group allocation, after adjusting for relevant confounders (sex, anaesthetic type and home setting)

|

|

Unstandardised coefficient for mILOA score (standard error) |

P |

|||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||

|

Group allocation (intervention v control) |

–4.12 (1.99) |

0.04 |

|||||||||||||

|

Sex (men v women) |

–0.11 (1.96) |

0.95 |

|||||||||||||

|

Anaesthetic type (general v spinal) |

–6.59 (2.64) |

0.02 |

|||||||||||||

|

Carer at home (v no carer at home) |

1.25 (1.95) |

0.52 |

|||||||||||||

|

Stairs at home (v no stairs at home) |

–1.53 (2.13) |

0.48 |

|||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||

Box 4 –

Linear regression analysis of the relationship between hospital length of stay and group allocation, after adjusting for relevant confounders (sex, anaesthetic type and home setting)

|

|

Unstandardised coefficient for length of stay (standard error) |

P |

|||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||

|

Group allocation (intervention v control) |

–16.80 (4.90) |

0.001 |

|||||||||||||

|

Sex (men v women) |

7.64 (4.83) |

0.12 |

|||||||||||||

|

Anaesthetic type (general v spinal) |

–15.60 (6.52) |

0.02 |

|||||||||||||

|

Carer at home (v no carer at home) |

–10.06 (4.82) |

0.04 |

|||||||||||||

|

Stairs at home (v no stairs at home) |

4.01 (5.26) |

0.45 |

|||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||

Box 5 –

Adjusted Kaplan–Meier analysis of the probability of discharge, after adjusting for sex, anaesthetic type, carer at home, and stairs at home*

* The probability of discharge in the intervention group was greater than for control patients at all time points (P < 0.001).

Box 6 –

Pain and pain management scores for the usual care (control) and intensive physiotherapy (intervention) groups during the first 3 post-operative days

|

Outcome |

Usual care |

Intensive physiotherapy |

P |

||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||

|

Number of patients |

46 |

46 |

|

||||||||||||

|

Post-physiotherapy pain scores, mean (SD) (maximum score: 10) |

|

|

|

||||||||||||

|

Day 1 |

5.3 (0.5) |

4.3 (0.4) |

0.16 |

||||||||||||

|

Day 2 |

4.2 (0.5) |

4.7 (0.5) |

0.44 |

||||||||||||

|

Day 3 |

4.0 (0.5) |

4.2 (0.5) |

0.79 |

||||||||||||

|

Opioid equivalence score, mean (SD)* |

|

|

|

||||||||||||

|

0–24 hours post-operative |

20.0 (14.0) |

20.9 (15.8) |

0.81 |

||||||||||||

|

24–48 hours post-operative |

26.3 (16.6) |

34.1 (26.7) |

0.12 |

||||||||||||

|

48–72 hours post-operative |

27.0 (19.8) |

29.2 (22.9) |

0.67 |

||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||

|

* Reference analgesic is oral morphine (mg). |

|||||||||||||||

[World Report] Helping Colombia’s landmine survivors

The Integral Rehabilitation Centre of Colombia in Bogotá is focused on improving the lives of people injured by landmines. Joe Parkin Daniels visited the centre to speak to doctors and patients.

[Comment] Offline: India—a great nation, marred

The biggest conundrum in health today is understanding the paradox between China and India. Both countries are justifiably proud of their rich civilisations—histories and philosophies that offer the world distinctive traditions and values. Their ideas and beliefs provide deeper and frequently far more interesting insights into human meaning than the empirical iciness of western cultures. Confucius, undergoing a 21st rehabilitation in both China and the west, is concerned with the sum total of truth in the universe.

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander health organisations: Online Services Report—key results 2014–15

This is the seventh national report on organisations funded by the Australian Government to provide health services to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people. In 2014–15: – 203 organisations provided primary health-care services to around 434,600 clients through 5.0 million client contacts and 3.5 million episodes of care; – 221 counsellors provided social and emotional wellbeing services to around 21,100 clients through 100,200 client contacts; – 67 organisations provided substance-use rehabilitation and treatment services to around 25,200 clients through 151,000 episodes of care.

Admitted patient care 2014–15: Australian hospital statistics

In 2014–15, there were about 10.2 million separations in Australia’s public and private hospitals: about 6.0 million of these occurred in public hospitals; 94% of separations were for acute care and 4% for rehabilitation care.Between 2010–11 and 2014–15: the number of separations increased overall by 3.5% on average each year; by 3.2% for public hospitals and by 4.0% for private hospitals; private health insurance funded separations increased by an average of 5.9% each year and; public patient separations increased by 2.7% each year.

more_vert

more_vert