Clinical record

A 59-year-old woman presented to her general practitioner with a lump in the left neck. She was a non-smoker, non-daily drinker and had no significant past medical history. Fine needle aspiration biopsy (FNAB) was performed and led to the diagnosis of a branchial cleft cyst. The mass collapsed after aspiration and the patient was managed conservatively by observation. In the year after diagnosis, re-emergence of the mass was noted by the GP at follow-up. Further investigations were declined on the patient’s presumption that the lesion was a benign branchial cleft cyst.

Two years after her initial diagnosis, the patient re-presented with a 1- to 2-month history of a sore throat and further increase in the size of the neck mass. On examination, a 7 cm mass was palpable, there was no overlying skin invasion and the mass was mobile to deep structures. Repeat FNAB of the neck mass was performed and revealed squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) with p16 positivity.

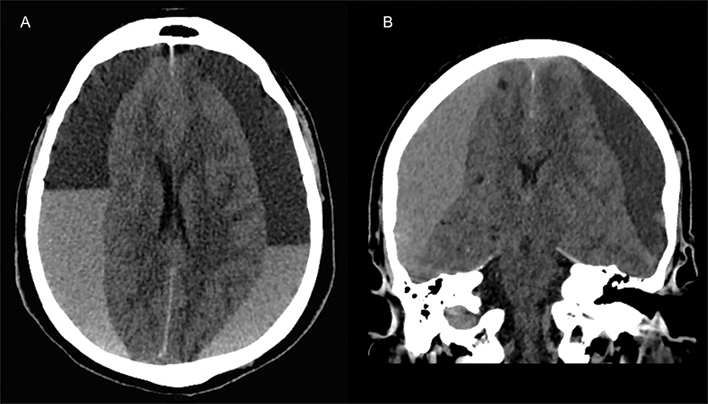

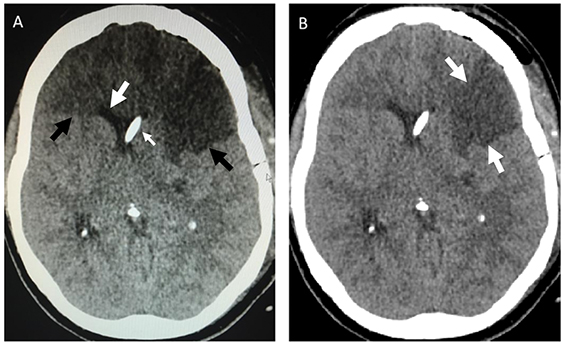

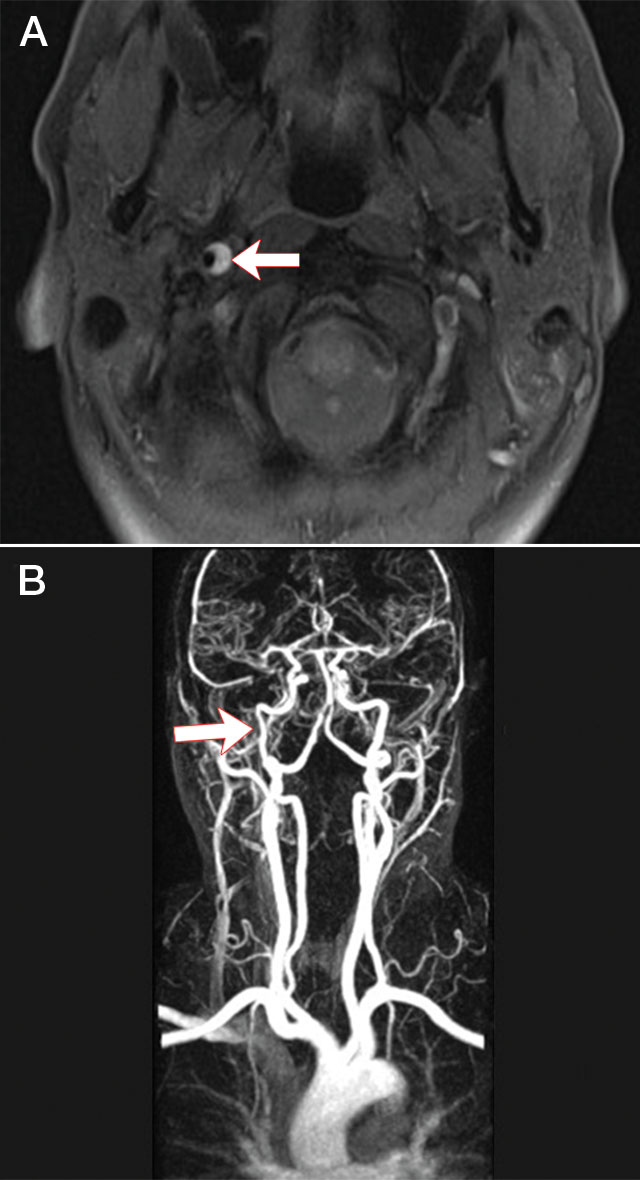

A staging computed tomography (CT) scan detected a lobulated tumour centred on the left tonsil invading the vallecula, base of tongue and parapharyngeal space. Further, a 27 mm cystic mass consistent with her initial lump was identified in the left level II group of lymph nodes, with additional necrotic nodes present at levels III and IV. A subsequent positron emission tomography scan confirmed increased uptake in these regions.

The patient was diagnosed with a T3 N2b M0 oropharyngeal SCC and was referred for radical chemoradiation. Expression of the surrogate marker p16 on cytological testing was highly suggestive that this was a human papilloma virus (HPV)-positive oropharyngeal SCC.

This case illustrates the diagnostic challenges faced in differentiating cystic nodal metastases from branchial cleft cysts, in the context of the increasing prevalence of HPV-related oropharyngeal SCC in Australia over the past two decades.1

HPV-related oropharyngeal SCC differs from traditional head and neck cancer in both its aetiology and clinical features; and because it is a relatively new clinical condition, GPs, radiologists and pathologists often do not recognise it as a potential diagnosis. Unlike traditional head and neck cancer, it occurs in a younger population who are frequently non-smokers and not heavy drinkers. Clinically, it most frequently presents with a neck mass, and often primary lesions are not easily discernible, as they are commonly small and in clinically difficult areas to examine, such as the base of the tongue or tonsil.

The natural disease pattern of oropharyngeal SCC is to metastasise to the cervical lymph nodes. In the setting of HPV-related cancer, these nodal metastases are frequently cystic in morphology and, as previously indicated, are frequently the first mode of presentation.2 Given the differing clinical features of HPV-related oropharyngeal cancer compared with non-HPV-associated oropharyngeal cancer, it is not uncommon for these nodal metastases to be misdiagnosed as branchial cleft cysts, as described in this case report. The proportion of metastatic SCCs in cysts initially presumed to be of branchial cleft origin has been reported to range from 11% to 21%.3,4

Misdiagnosis can negatively affect patient prognosis as it delays treatment, allows for further disease progression and increases the potential for metastatic spread. Alternatively, proceeding to excisional biopsy of a cystic mass suspected to be a branchial cleft cyst without adequate investigation for an occult primary can lead to tumour spillage into the surrounding tissues.

Differences in the demographics between branchial cleft cysts and cystic nodal metastases may aid clinicians in accurate diagnosis. While branchial cleft cysts may occur at any age, they most commonly present in early adulthood in the second and third decade of life.5 The reported mean age for cervical cystic masses histologically confirmed as branchial cleft cysts ranges from 32 to 37 years.6,7 In contrast, cystic nodal metastases present later, with a reported mean age ranging from 53 to 57.8 years.6,7 Particular attention must be paid to cervical cysts in patients over 40 years of age, as 44% of cystic masses in this patient population are reported to be malignant in origin.8 The most commonly represented lesions associated with cystic metastases are HPV-related head and neck cancer and thyroid papillary carcinoma.9

CT is a mainstay in the diagnosis and staging of head and neck cancer and plays an important role in differentiating benign lesions of the neck from malignant cystic lymphadenopathy. On contrast-enhanced CT, there is homogeneous attenuation throughout the substance of branchial cleft cysts.6 Features suggestive of malignancy include the presence of septations, heterogeneous attenuation and extracapsular spread.6,7 Significant overlap between the radiological features of benign and malignant cysts is, however, present. Repeated local infection involving a branchial cleft cyst may confer a radiological appearance similar to that of nodal metastasis of an SCC.7 In one study, 31% of cystic nodal metastases were reported as benign in appearance, while 38% of branchial cleft cysts had aggressive features mimicking nodal metastases.6 Evidently, isolated use of CT in evaluating a cystic neck mass confers a high degree of misdiagnosis.

FNAB cytology is the current standard of care in diagnostic workup of solid masses of the neck and is reported to have an overall sensitivity of 92% and a positive predictive value of 100% for head and neck carcinomas.10 Unfortunately, this has not been the common experience with cystic lesions, for which its role remains controversial. Reported sensitivities range from 33% to 55%,11 with a false-negative rate of up to 50%.2 The aspirate of cystic metastatic nodes may be difficult to interpret as a result of hypocellularity from the dilutional effect of the cyst fluid.2 There is commonly an associated inflammatory reaction within the cystic nodes, resulting in large quantities of degenerating epithelial cells, inflammatory cells and cellular debris within the aspirate. These cytological features overlap considerably with those of branchial cleft cysts12 and can lead to misdiagnosis.

Despite these limitations, FNAB still retains some relevance in the diagnosis of cystic lesions. Further, with the emergence of molecular analysis techniques, the detection of HPV DNA and thyroglobulin within fine needle aspirates may facilitate the pathological diagnosis of malignant cystic lymphadenopathy and detection of occult primary tumours. The presence of HPV DNA or thyroglobulin in aspirates is strongly correlated with HPV-related oropharyngeal SCC and thyroid cancer, respectively.13,14 Although these tests are primarily used for research purposes at present, their utility may expand to the clinical setting in future to help to differentiate benign and malignant cystic neck lesions.

Differentiating cystic nodal metastases from branchial cleft cysts is an important, albeit sometimes difficult, diagnostic challenge. With the growing prevalence of HPV-related oropharyngeal SCC in Australia, we conclude that metastatic lymphadenopathy should be considered as the primary provisional diagnosis in the adult population with cystic neck masses until proven otherwise. We encourage caution in the interpretation of neck masses as benign by isolated use of either CT or FNAB. Clinicians should use these modalities in conjunction with each other and, if necessary, include referral for an ear, nose and throat specialist opinion to increase diagnostic accuracy.

Lessons from practice

-

HPV-related oropharyngeal cancer is an increasingly common and relatively new entity that differs from traditional head and neck cancer in its aetiology, epidemiology, clinical features and prognosis.

-

Lateral cystic neck masses in adults are often misdiagnosed as branchial cleft cysts and should be considered as metastatic lymphadenopathy until proven otherwise.

-

Isolated use of computed tomography or fine needle aspiration biopsy in evaluating a neck mass can lead to misdiagnosis. Instead, these modalities should be used in conjunction with each other and, if necessary, include referral for an ear, nose and throat specialist opinion to increase diagnostic accuracy.

-

The emergence of molecular analysis techniques for detecting HPV DNA and thyroglobulin in fine needle aspirates may assist clinicians in the diagnosis of occult primary tumours with cystic nodal metastasis.

more_vert

more_vert