Lung cancer causes more deaths than any other cancer, and is a leading cause of disease-related burden in Australia.1 The United States National Lung Screening Trial (NLST) showed that screening high risk current and former smokers for lung cancer with low dose chest computed tomography (LDCT) can significantly reduce lung cancer mortality.2 LDCT lung cancer screening is recommended in the US for eligible individuals.3

Unlike other cancer screening programs that select participants according to the risk factors of age and sex, eligibility for lung cancer screening is more complex. The current US screening criteria, as defined by the US Preventive Service Task Force (USPSTF), are that current or former smokers are eligible if they are aged 55–80 years, have a smoking history of at least 30 pack-years, and, if a former smoker, have quit less than 15 years ago.3 However, this approach is not necessarily the most efficient for identifying those who may benefit from screening.4 Using probabilistic multivariate lung cancer risk prediction models to select individuals for screening may improve overall efficiency and cost-effectiveness, and are recommended by international organisations.5–7

The PLCOm2012 lung cancer risk model was developed during the US Prostate, Lung, Colorectal, Ovarian Screening (PLCO) Trial, and has been validated in the NLST cohort.8 This model uses data on age, smoking status, duration and intensity, family history, body mass index (BMI), and comorbidities (including self-reported chronic obstructive pulmonary disease [COPD], chronic bronchitis and emphysema) to estimate an individual’s risk of developing lung cancer within 6 years.8 A PLCOm2012 lung cancer risk of greater than 1.5% has been proposed as an alternative lung cancer screening eligibility criterion.9

COPD is an independent risk factor for the development of lung cancer, and self-reported, doctor-diagnosed COPD and chronic bronchitis or emphysema are included in the PLCOm2012 risk prediction model (but not in the USPSTF eligibility criteria).8 There are, however, significant differences in the proportions of individuals who report a diagnosis of COPD, who have symptoms consistent with COPD, or who have airflow obstruction detectable by spirometry.10 Including airflow obstruction improves the accuracy of a lung cancer risk prediction that does not incorporate self-reported COPD.11 Incorporating spirometry results into eligibility assessment for lung cancer screening has been suggested, but the impact of adding spirometry-defined COPD to the existing eligibility criteria of self-reported COPD or symptoms consistent with COPD is not known.12

In Australia, about 2.2 million people aged 55–75 years are current or former smokers, but the proportion of those eligible for lung cancer screening, using either USPSTF or PLCOm2012 criteria, is unknown.13 Estimating the proportion of people eligible for lung cancer screening will both aid policy makers when planning future capacity and assessing infrastructure requirements, and help estimate screening participation rates.

The aims of this study were to estimate the proportion of an Australian cohort that is eligible for lung cancer screening, and to examine the utility of including spirometry-defined COPD as part of screening eligibility assessment.

Methods

The Busselton Healthy Ageing Study (BHAS) is a cross-sectional study of adults born between 1946 and 1964 who live in the Busselton Shire of Western Australia.14 Participants were recruited sequentially at random between 2010 and 2013 from the electoral roll; the participation rate was greater than 80% of contacted individuals. Participants completed a self-administered questionnaire and physical assessments, including spirometry. The upper age limit of participants included in our study (68 years) was determined by the BHAS design.

Smoking status, duration and intensity were self-reported. Ever-smokers responded positively to “Have you ever smoked cigarettes?” Current smokers responded positively to “Do you currently smoke manufactured or hand-rolled cigarettes?”, and former smokers responded negatively. Pack-years of smoking were determined by multiplying the duration of smoking in years by the number of 20-cigarette packs smoked each day. Personal history of any cancer other than non-melanomatotic skin cancer, family history of lung cancer, and other demographic information were self-reported.

BMI was calculated from the measured height and weight. Pre- and post-bronchodilator forced expiratory volume in one second (FEV1) and forced vital capacity (FVC) were measured using an EasyOne spirometer (NDD Medical Technologies) before and after administration of 200 μg of inhaled salbutamol with a metered dose inhaler and spacer. Participants were asked to withhold any bronchodilator medication, if possible, for 12 hours before testing.

Individuals were excluded from the analysis if they had a history of lung cancer, if BMI or demographic data were missing, or there was insufficient data on smoking duration or intensity to calculate the number of pack-years.

Lung cancer risk was calculated with the PLCOm2012 6-year lung cancer risk prediction model.8 For the purposes of this model, COPD was defined in three ways:

-

self-reported, doctor-diagnosed COPD, defined as a positive response to “Has your doctor ever told you that you had COPD?”;

-

symptoms consistent with COPD, defined as a positive response to “Do you cough on most days for as much as 3 months each year?” or “Do you bring up phlegm from your chest on most days for as much as 3 months each year?” or “Has your chest made a wheezing or whistling sound in the last 12 months?”; and

-

spirometry-defined COPD, defined by the presence of post-bronchodilator airflow obstruction (FEV1/FVC ratio < 0.7), excluding those with more than 12% improvement in FEV1 or FVC after bronchodilator medication.

Eligibility for lung cancer screening was based on two criteria: the current USPSTF recommendation3 and a PLCOm2012 6-year lung cancer risk of > 1.5%, as recommended by Tammemägi and colleagues.8 To estimate the proportion of the Australian population who are eligible for screening, an estimate of 2.2 million Australians aged 55–75 years who are current or former smokers13 was multiplied by our estimate of the proportion of potentially eligible ever-smokers in the Busselton population according to USPSTF criteria.

Statistical analyses were performed in SPSS 22 (IBM); 95% confidence intervals for proportions were calculated using continuity adjustment. Comparisons of the proportions of independent and dependent samples were performed with χ2 and McNemar tests respectively. Independent sample t tests compared the means of independent samples. Statistical significance was defined as P < 0.05.

Ethics approval

The BHAS and the reported study received human research ethics approval from the University of Western Australia Human Research Ethics Committee (references RA/4/A/2203, RA/4/1/7891).

Results

Of all 3586 BHAS participants aged 50–68 years, 1903 (53.1%) were current or former smokers. Of these ever-smokers, 36 were excluded (16 had incomplete smoking information, 15 reported smoking less than one cigarette per day, one had prior lung cancer, and demographic or BMI data were missing for four), leaving 1867 participants for the analysis. In the 55–68-year-old age group, 1260 (49.9%) were ever-smokers (including 240 [6.7%] current smokers), 1241 (49.2%) were never-smokers, and 22 (0.9%) had incomplete smoking data.

The demographic details of all BHAS ever-smokers in two age groups, 50–68 years and 55–68 years, are summarised in Box 1. The 55–68-year-old age group was selected as corresponding to the age cohort currently eligible for lung cancer screening in the US.

Eligibility for lung cancer screening

Of ever-smokers aged 55–68 years, 254 (20.1%; 95% CI, 17.9–22.3%) would be eligible for screening according to USPSTF criteria. Using the PLCOm2012 criteria with self-reported COPD, fewer people (225, 17.9%) would be eligible (95% CI, 15.8–20.0%; P = 0.004).

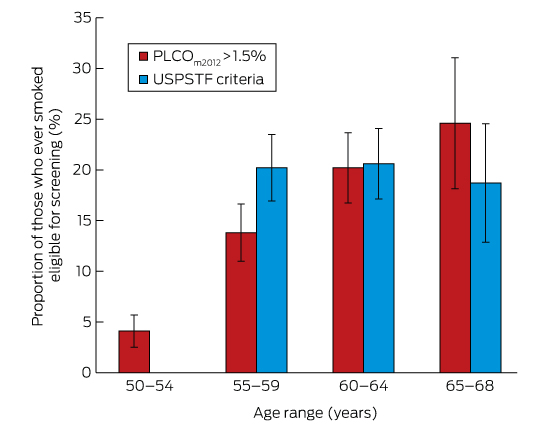

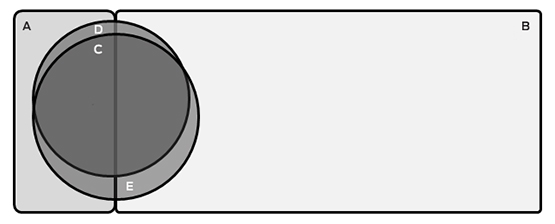

The proportion of ever-smokers eligible for screening increased with age in the PLCOm2012 model, but was stable when using USPSTF criteria (Box 2). Of the entire age-defined cohort, 2.6% would be eligible using PLCOm2012 criteria but not according to USPSTF criteria, and 4.9% would be eligible using USPSTF criteria but not PLCOm2012 criteria; 15.2% would be eligible according to both criteria sets (Box 3). This suggests that about 450 000 individuals in Australia may be eligible for lung cancer screening.

Effect of COPD definition on lung cancer risk and eligibility

Of the ever-smokers in the BHAS population, 1191 had concurrent spirometry, of whom 782 were aged 55–68 years. Using the PLCOm2012 criteria, the proportion eligible for screening was 16.4% (using self-reported COPD), 18.8% (symptoms consistent with COPD), or 17.5% (airflow obstruction on spirometry) (Box 4). Fewer people were eligible for screening using self-reported than spirometry-defined COPD (P < 0.01); there was no statistical difference between the proportions of eligible participants when spirometry-defined or symptom-defined COPD was used (P = 0.06). When spirometry-defined COPD was added to symptom-defined COPD to determine PLCOm2012 risk, an additional seven participants (0.9%) would have been eligible for screening. If normal spirometry was used to exclude COPD in those who reported symptoms of COPD, 17 participants (2.1%) would be deemed ineligible for screening.

Of the 409 ever-smokers aged 50–55 years (and therefore ineligible for screening according to current criteria) with spirometry data, 18 (4.4%; 95% CI, 2.8–6.9%), 36 (8.8%; 95% CI, 6.4–11.9%) or 25 (6.1%; 95% CI, 4.2–8.9%) would have been eligible based on a PLCOm2012 risk greater than 1.5% when COPD was defined by doctor diagnosis, symptoms, or spirometry respectively.

Discussion

Our study suggests that 17.9% (PLCOm2012) to 20.1% (USPSTF criteria) of current or former smokers aged 55–68 years in Busselton would be eligible for lung cancer screening, corresponding to 8.9% (PLCOm2012) and 10% (USPSTF) of all those in the BHAS cohort aged 55–68 years. This is the first time that the proportion of ever-smokers eligible for lung cancer screening has been estimated in an Australian population. While small studies have shown the feasibility of lung cancer screening in Australia, significant hurdles remain before screening is endorsed locally.15–18

Our finding that the USPSTF criteria identified a higher proportion of eligible individuals than the PLCOm2012 criteria is consistent with previous reports.9 Our study could not validate the predictive performance of each criterion because mature lung cancer outcomes were not available. Retrospective studies suggest that the PLCOm2012 model performs better than the USPSTF criteria in identifying high risk individuals, but prospective impact analyses in screening cohorts are required to determine which eligibility criteria should be preferred in the Australian context.

There have been four previous estimates of the proportion of the US population who would be eligible for screening (Box 5).9,19–21 Three of these studies estimated that 18.8–24.4% of ever-smokers and 10.5–14.3% of all individuals in the respective age cohorts were eligible for screening according to USPSTF criteria.19–21 These estimates are broadly comparable with our estimates of the proportion of eligible individuals in the BHAS. On the other hand, fewer BHAS ever-smokers would be eligible for screening than estimated for the PLCO intervention arm ever-smokers (17.9% v 34.6%; P < 0.001).9 This observation may partly be explained by differences in tobacco exposure between the cohorts; the proportion of current and former smokers were similar, but BHAS participants reported lower smoking intensity (mean pack-years, BHAS v PLCO: current smokers, 32.1 v 40.8, P < 0.001; former smokers, 17.8 v 25.8; P < 0.001).22

There are two possible explanations for the lower smoking intensity in the BHAS cohort. The first relates to historical trends in smoking. Enrolment for the PLCO trial occurred between 1993 and 2001, whereas BHAS enrolment commenced in 2010.14,23 Smoking consumption in Australia declined significantly between 2001 and 2010 among both men and women.24 The second explanation is a potential healthy community effect after repeated cross-sectional health surveys in the Busselton community since 1966.14

The current study has highlighted the known challenges in defining and diagnosing COPD. Only 1% of 55–68-year-old BHAS ever-smokers reported being diagnosed with COPD, whereas 13.8% met the spirometric definition of COPD and 35.0% reported symptoms consistent with the disease. A similar discrepancy was previously described in a larger Australian study.10 Airflow obstruction on spirometry is not only crucial to diagnosing COPD, but is an independent predictor of increased lung cancer incidence in screening studies, and may predict overdiagnosis.12 Incorporating spirometry into screening eligibility assessment has been suggested, but this would require direct patient contact.12 Our results suggest that performing spirometry is unlikely to meaningfully improve the identification of eligible individuals, with just one additional individual from every 100 ever-smokers assessed becoming eligible. We therefore contend that, in the absence of more epidemiological data comparing the relative lung cancer risks associated with airflow obstruction and with symptoms or self-reported COPD, defining COPD on the basis of symptoms is an appropriate surrogate measure for spirometry.

Policy makers in jurisdictions that recommend population-based cancer screening, such as Australia, are faced by significant implementation challenges.15,25 No state or federal database contains the necessary data for directly identifying the estimated 10% of the age-defined population eligible for screening. Population-based recruitment strategies for lung cancer screening must therefore currently engage with and assess the eligibility of a broader population of ever-smokers, the majority of whom will be ineligible. The feasibility and unintentional impact of this recruitment approach is not known.

Smoking cessation in one lung cancer screening study reduced all-cause mortality by up to 43%.26 Almost half of BHAS current smokers (42.9%; 103 of 240 current smokers) were ineligible for screening, regardless of the criteria used. Providing smoking cessation support without LDCT screening to ineligible current smokers who engage with a screening program may be a pragmatic way to combine primary prevention and early detection of lung cancer.

Of the BHAS ever-smokers aged 50–55 years, 4.4–8.8% had PLCOm2012 lung cancer risk sufficient to potentially benefit from screening, depending on the definition of COPD used. This may represent an additional population at risk who may benefit from lung cancer screening at a lower age threshold than currently recommended, although internationally there is little prospect of such a change.27

There are several potential limitations to this study. The upper age limit of our BHAS participants was 68 years, younger than the maximum recommended screening age of 80 years.3 This study may therefore have underestimated the proportion of the population potentially eligible for screening, as PLCOm2012 risk increases with age.21 Ethnic background has an impact on lung cancer risk, and the BHAS participants were almost exclusively European in origin, which is not representative of the broader Australian population, although the Busselton population age distribution and smoking demographic can be broadly generalised to the wider Australian population. Other lung cancer risk prediction models are being used to select individuals for lung cancer screening studies, but it was not possible to assess them, as they include variables (such as asbestos exposure) not recorded by the BHAS.6 The definition of COPD in the PLCOm2012 model is self-reported COPD, chronic bronchitis or emphysema, more inclusive than the definition used in the BHAS. We were unable to validate the PLCOm2012 model, as 6-year lung cancer outcomes are not available.

In conclusion, we estimate that between 17.9% and 20.1% of all current or former smokers aged 55–68 years in the BHAS population would be eligible for lung cancer screening, depending on the criteria applied. Symptom-defined COPD may be an appropriate surrogate measure for spirometric testing for determining the presence of COPD as part of the assessment of lung cancer screening eligibility.

Box 1 –

Demographic characteristics of ever-smokers in the Busselton Healthy Ageing Study

|

|

50–68 years old

|

55–68 years old

|

|

|

Number

|

1867

|

1260

|

|

Age (years), mean ± SD

|

58.0 ± 4.8

|

60.7 ± 3.4

|

|

Sex (women)

|

927 (49.7%)

|

603 (47.9%)

|

|

Ethnic background

|

|

|

|

European

|

1848 (99.0%)

|

1249 (99.1%)

|

|

Asian

|

12 (0.6%)

|

5 (0.4%)

|

|

Aboriginal and/or Torres Strait Islander

|

6 (0.3%)

|

5 (0.4%)

|

|

Māori or Pacific Islander

|

1 (0.1%)

|

1 (0.1%)

|

|

Body mass index (kg/m2), mean ± SD

|

28.46 ± 4.90

|

28.70 ± 4.95

|

|

Smoking status

|

|

|

|

Current

|

368 (19.7%)

|

240 (19.0%)

|

|

Former

|

1499 (80.3%)

|

1020 (81.0%)

|

|

Total pack-years, mean ± SD

|

|

|

|

Ever-smokers

|

19.2 ± 19.6

|

20.5 ± 20.7

|

|

Current smokers

|

31.5 ± 20.0

|

32.1 ± 19.3

|

|

Former smokers

|

16.2 ± 18.4

|

17.8 ± 20.1

|

|

Highest education level obtained

|

|

|

|

Did not complete high school

|

36 (1.9%)

|

27 (2.1%)

|

|

High school

|

1000 (53.6%)

|

702 (55.7%)

|

|

TAFE or other college

|

555 (29.7%)

|

352 (27.9%)

|

|

University

|

276 (14.8%)

|

179 (14.2%)

|

|

Previous cancer (excluding non-melanomatotic skin cancer)

|

155 (8.3%)

|

122 (9.7%)

|

|

Family history of lung cancer

|

146 (7.8%)

|

106 (8.4%)

|

|

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD)

|

|

|

|

Self-reported COPD

|

16 (0.9%)

|

13 (1.0%)

|

|

Symptoms consistent with COPD

|

617 (33.0%)

|

441 (35.0%)

|

|

Spirometry-defined COPD

|

179/1191 (15.0%)

|

108/782 (13.8%)

|

|

|

TAFE = Technical and Further Education.

|

Box 2 –

Eligibility for lung cancer screening of 1260 55–68-year-old ever-smokers in Busselton, according to USPSTF and PLCOm2012 criteria*

Box 3 –

Schematic representation of the proportion of current and former smokers eligible for screening

Box 4 –

Proportions of 782 ever-smokers aged 55–68 years eligible for screening based on PLCOm2012 criteria, using different definitions of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD)

|

COPD definition for estimating PLCOm2012 lung cancer risk

|

PLCOm2012 risk > 1.5%

|

P*

|

|

|

Self-reported COPD

|

128 (16.4%; 95% CI, 13.8–19.0%)

|

< 0.01

|

|

Symptom-defined COPD

|

147 (18.8%; 95% CI, 16.1–24.5%)

|

0.06

|

|

Spirometry-defined COPD

|

137 (17.5%; 95% CI, 14.8–20.2%)

|

—

|

|

|

* v spirometry-defined COPD (McNemar test).

|

Box 5 –

Summary of studies reporting proportions of the population aged 55 years or more who are eligible for lung cancer screening

|

|

BHAS

|

PLCO intervention arm9,22

|

US Health and Retirement Study19

|

US National Health Interview Survey20

|

US National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey18

|

|

|

Sample size

|

2523

|

77 445

|

16 901

|

7138

|

2562

|

|

Recruitment period

|

2010–2013

|

1993–2001

|

2012

|

2011

|

2007–2012

|

|

Age range, years

|

55–68

|

55–74

|

55–80

|

55–74

|

55–77

|

|

Smoking status

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Never

|

49.2%

|

45.1%

|

42.5%

|

NR

|

NR

|

|

Current

|

9.5%

|

10.4%

|

14.4%

|

NR

|

NR

|

|

Former

|

40.4%

|

42.0%

|

39.6%

|

NR

|

NR

|

|

Missing or incomplete

|

0.9%

|

2.5%

|

3.5%

|

NR

|

NR

|

|

Eligible individuals as proportion of entire cohort

|

|

USPSTF criteria

|

10.0%

|

19.6%

|

10.5%

|

14.3%

|

NR

|

|

PLCOm2012 > 1.5%

|

8.9%

|

17.9%

|

NR

|

NR

|

NR

|

|

Eligible individuals as proportion of cohort of all ever-smokers

|

|

USPSTF criteria

|

20.1%

|

38.0%

|

18.8%

|

NR

|

24.4%

|

|

PLCOm2012 > 1.5%

|

17.9%

|

34.6%

|

NR

|

NR

|

9–35%, depending on ethnicity*

|

|

|

BHAS = Busselton Healthy Ageing Study; NR = not reported; PLCO = Prostate, Lung, Colorectal and Ovarian Trial; USPSTF = United States Preventive Services Task Force. * Extrapolated from figure 1 in reference .

|

more_vert

more_vert