We commend Guy Rutty and colleagues on their Article (July 8, p 145)1 recommending the use of post-mortem imaging at autopsy. A fundamental role of the pathologist is to assist the coroner in fulfilling their statutory duty in establishing the cause and circumstances of death. How precise that cause of death needs to be depends on the requirements of the relevant legislation. To what extent pathology and radiology can satisfactorily provide the information to inform this advice depends on the circumstances of the case and, most importantly, on the questions being asked by interested parties, including families.

Preference: Radiology

1000

Relationships with industry

BY DR CHRIS MOY, CHAIR. AMA ETHICS AND MEDICO LEGAL COMMITTEE

A major priority for the AMA’s Ethics and Medico-Legal Committee (EMLC) will be the review of the Position Statement on Medical Practitioners’ Relationships with Industry 2012. The statement provides guidance for doctors on maintaining ethical relationships with “industry”, including the pharmaceutical industry, medical device and technology industry, other health care product suppliers, health care facilities, medical services such as pathology and radiology, and other health services such as pharmacy and physiotherapy.

The current Statement encompasses the following sections:

- medical education;

- managing real and potential conflicts of interest;

- industry sponsored research involving human participants including post-marketing surveillance studies;

- meetings and activities organised independent of industry;

- meetings and activities organised by industry;

- hospitality and entertainment;

- use of professional status to promote industry interests;

- remuneration for services;

- product samples;

- dispensing and related issues; and

- relationships involving industry representatives.

Doctors’ primary duty is to look after the best interests of their patients. To do so, doctors must maintain their professional autonomy, clinical independence and integrity, and have the freedom to exercise professional judgement in the care and treatment of patients without undue influence by third parties (such as the pharmaceutical industry or governments).

But what happens when the impetus to change the relationship with industry comes from within the profession itself? For example, the AMA’s current policy on doctors and dispensing states that:

11.1 Practising doctors who also have a financial interest in dispensing and selling pharmaceuticals or who offer their patients’ health-care related or other products are in a prima facie position of conflict of interest.

11.2 Doctors should not dispense pharmaceuticals or other therapeutic products unless there is no reasonable alternative. Where dispensing does occur, it should be undertaken with care and consideration of the patient’s circumstances.

In recent years, we have heard from members who believe this position is too strict and doctors should be able to dispense pharmaceutical products, arguing that it’s more convenient for patients and leads to better compliance. For example, patients may be more likely to fill their prescriptions onsite at the doctor’s office than if they have to go offsite to a pharmacy. In addition, the doctor is there to answer any questions relevant to the prescription which will reduce pharmacy call backs and waiting times.

Historically, the AMA has strongly advocated that doctors do not make money from prescriptions. Allowing doctors to dispense pharmaceuticals or other therapeutic products (other than in exceptional circumstances) would be a fundamental shift in this position – but is that a sufficient reason not to change it?

After all, dispensing pharmaceuticals or other therapeutic products is not in itself unethical so long as it is undertaken in accordance with good medical practice. Unfortunately, however, there can still be a strong perception of a conflict of interest, particularly if doctors are making a profit rather than just recovering costs. So for many doctors – but more importantly our patients and the wider community who are our ultimate judges – this is a line which should not be crossed.

These are the types of issues the EMLC will consider in reviewing this policy and we will endeavour to seek members’ views during the process.

The EMLC will also be developing an overarching policy on managing interests, highlighting the potential for professional and personal interests to intersect, and at times compete, during the course of a doctor’s career. While a real, or perceived, conflict of interest is by no means a moral failing, it is important that doctors are able resolve any potential for conflict in the best interests of patients.

The Position Statement on Medical Practitioners’ Relationships with Industry 2012 is accessible on the AMA’s website at position-statement/medical-practitioners-relationship…. If you would like to suggest any amendments to the current Statement, please forward them to ethics@ama.com.au.

[Comment] Targeted coronary post-mortem CT angiography, straight to the heart

Soon after the discovery of x-rays in November, 1895, by Wilhelm Conrad Röntgen, the first post-mortem radiographs were obtained; one example being the post-mortem angiography done by Haschek and Lindenthal in January, 1896.1 However, it took the pioneering work of Richard Dirnhofer and Michael Thali with their Virtopsy group to regain wider attention for post-mortem radiology and more specifically post-mortem CT (PMCT).2 In the past decades, substantial progress has been made, although the main focus of attention has been on adult forensic PMCT.

Art and Medicine

By Dr Jim Chambliss

It is often said that a picture speaks a thousand words.

Contemporary medical technology provides incredibly intricate pictures of external and internal human anatomy.

However, technology does not communicate holistic representations of the social, behavioural and psychosocial impacts associated with illness and the healing process.

Studies have shown that increased reliance on reports from expensive laboratory tests, radiology and specialised diagnostic technology has resulted in inadequacy of physical examination skills; decline in patient empathy, and less effective doctor/patient communication.

Having commenced in May this year and continuing until July 8, continuing professional development workshops which explore and promote the value of art expression in the development of observation skills, human sensitivity and relevant healthcare insights will be presented at the National Gallery of Victoria exhibition of the original works of Vincent van Gogh.

The program will incorporate empirical research to illustrate the way neuropsychological conditions can influence art and creativity. The objectives of the workshops are to:

• advance understanding of the impact of medical, psychological and social issues on the health and wellbeing of all people;

• promote deeper empathy and compassion among a wide variety of professionals;

• enhance visual observation and communication skills; and

• heighten creative thinking.

Over the last 15 years, the observation and discussion of visual art has emerged in medical education, as a significantly effective approach to improving visual observation skills, patient communication and empathy.

Pilot studies of implementing visual art to teach visual diagnostic skills and communication were so greatly effective that now more than 48 of the top medical schools in the USA integrate visual arts into their curriculum and professional development courses are conducted in many of the most prestigious art galleries and hospitals.

The work of Vincent van Gogh profoundly illustrates the revelations of what it means to be uniquely human in light of neurological characteristics, behavioural changes and creative expression through an educated, respectful and empathic perspective.

The exact cause of a possible brain injury, psychological illness and/or epilepsy of van Gogh is unknown.

It is speculated by numerous prominent neurologists that Vincent suffered a brain lesion at birth or in childhood while others opine that it is absinthe consumption that caused seizures.

Two doctors – Felix Rey and Théopile Peyron – diagnosed van Gogh with epilepsy during his lifetime.

Paul-Ferdinand Gachet also treated van Gogh for epilepsy, depression and mania until his death in 1890 at the age of 37.

After the epilepsy diagnosis by Dr Rey, van Gogh stated in a letter to his brother Theo, dated 28 January 1989: “I well knew that one could break one’s arms and legs before, and that then afterwards that could get better but I didn’t know that one could break one’s brain and that afterwards that got better too.”

Vincent did not, by any account, demonstrate artistic genius in his youth. He started painting at the age of 28 in 1881.

In fact, his erratic line quality, compositional skills and sloppiness with paint were judged in his February 1886 examinations at the Royale Academy of Fine Arts, Antwerp to be worthy of demotion to the beginners’ painting class. His original drawings and paintings were copies from others’ art, while his sketches in drawing class showed remarkably different characteristics.

Increased symptoms of epilepsy and exposure to seizure triggers (absinthe and sleep deprivation) ran parallel with van Gogh’s most innovative artistic techniques and inspirations following his move to Paris in 1886 to 1888.

These symptoms increased, accompanied by breathtaking innovation following his move to Arles, France in 1888 and his further decline in mental and physical health.

In Paris he was exposed to the works of many of the most famous impressionistic and post impressionistic painters, but so much of his new techniques and imagery were distinctly innovative in detail without traceable influences from others.

While in Paris his work transitioned from drab, sombre and realistic images to the vibrant colours and bold lines.

His ebb-and-flow of creative activity and episodes of seizures, depression and mania were at their most intense in the last two years of his life when he produced the greatest number of paintings.

His works are among the most emotionally and monetarily valued of all time. Vincent’s painting of Dr Gachet (1890) in a melancholy pose with digitalis flowers – used in the treatment of epilepsy at that time – sold for $US82.5 million in May, 1990, which at the time set a new record price for a painting bought at auction.

Healthcare professionals and art historians have written from many perspectives of other medical and/or psychological conditions that impacted van Gogh’s art and life with theories involving bipolar disorder, migraines, Meniere’s decease, syphilis, schizophrenia, alcoholism, emotional trauma and the layman concept of ‘madness’.

What was missing as a basis to best resolve disputes over which mental or medical condition(s) had significant impact on his life was a comprehensive foundation of how epilepsy or mental illness can influence art and possibly enhance creativity based on insights from a large group of contemporary artists.

Following a brain injury and acquired epilepsy I gained personal insight into what may have affected the brain, mind and creativity of van Gogh and others who experience neurological and/or psychological conditions.

The experience opened my eyes to the medical, cognitive, behavioural and social aspects of two of the most complex and widely misunderstood human conditions.

Despite having no prior experience or recognisable talent, I discovered that my brain injury/epilepsy had sparked a creative mindset that resulted in a passion for producing award-winning visual art.

I enrolled in art classes and began to recognise common topics, styles and characteristics in the art of contemporary and famous artists who are speculated or known to have had epilepsy, such as Vincent van Gogh, Lewis Carroll, Edward Lear and Giorgio de Chirico.

Curiosity for solving the complex puzzle of how epilepsy could influence art led me to pursue a Masters in Visual Art which included a full course exclusively about Vincent van Gogh.

I subsequently obtained the world’s first dual PhD combining Visual Arts, Medicine and Art Curation at the University of Melbourne.

The PhD Creative Sparks: Epilepsy and enhanced creativity in visual arts (2014) was based on the visual, written and verbal insights from more than 100 contemporary artists with epilepsy and provided:

• objective and subjective proof that epilepsy can sometimes enhance creativity – supported by brain imaging illustrating how that can occur;

• a comprehensive inventory of the signature traits of neurological and psychological conditions that have significant interpretive value in healthcare practice and consideration in art history;

• the largest collection of images of the visual narratives from people with epilepsy;

• comparative data to distinguish epilepsy from other medical and mental conditions; and

• the Creative Sparks Art Collection and Website – artandepilepsy.com.

Interest in these research discoveries and art exhibitions provided opportunities for me to deliver presentations at national and international universities, hospitals and conferences. Melbourne University Medical School sponsored an innovative series of workshops through which to teach neurology and empathy by an intriguing new approach.

Jim Chambliss has a dual PhD in Creative Arts and Medicine and has explored the ways epilepsy and other health conditions can influence art and enhance creativity.

Information about his Art and Medicine Workshops involving Vincent van Gogh can be obtained by visiting artforinsight.com or artandepliepsy.com

.

Changing our professional culture – what can we do as individuals?

BY DR KATHERINE KEARNEY

Culture is defined as the “total of human behaviour patterns and technology communicated from generation to generation” (New Webster’s Dictionary). How do you define yourself within the broad umbrella of medicine? Are you a doctor, and connect broadly with other doctors as colleagues, or do you feel a stronger association with your fellow nephrologists, cardiothoracic surgeons or general practitioners? Who do you consider your peers and your fellow professional representatives to the broader community? How does that influence your interaction with other doctors, other healthcare professionals and healthcare delivery systems?

Healthcare delivery is a team sport. Broadly speaking, our teams can be as large as our entire hospital operational staff, to “geriatrics team C” with a few consultants, a registrar and an intern. To make it easier for ourselves, we often choose to identify with those closest to us in personality and in daily interactions. I believe it is important to think about the broader profession and our professional culture. What is our professional culture, and what impact is it having on the health and wellbeing of doctors, broadly speaking?

Undoubtedly, medicine is a culture of high achievement and has always been so. High stakes selection processes are becoming universal given the enormous numbers of doctors in training entering the prevocational system as interns, approximately 3,300 in 2015 (MTRP report). It is becoming the norm that trainees have committed early, and committed fully to pursuing a wide range of extracurricular activities such as research, audits, extra qualifications like graduate diplomas or masters, sit on committees relevant to their future goals and have lofty achievements outside of medicine in their hobbies; climbing mountains, volunteer work, high level sporting achievements.

The pressure is immense, amongst a group that is naturally incredibly high achieving. I’ve certainly heard statements from tremendously successful senior colleagues that they would never have gotten onto their training pathway in the current era. Relentless accumulation of accomplishments does not necessarily make for a happy, fulfilled person nor a superior clinician – we see this in disconnects between CVs full of achievements and a lack of correlation with clinical success. I’m as guilty as anyone else at relieving my anxiety about the future of my career by punishing schedules of extracurricular activities. What are truly important achievements to us individually, and how can we bring clarity by appropriately setting personal and professional goals?

Throughout most training pathways, there are high stakes barrier assessments – some of which, such as physicians college exams, are only held on an annual basis. A failed assessment reverberates around hospital and medical community and has a huge impact on the trainee. With this increasingly competitively environment for training positions, as well as failing being challenging personally for those who’ve failed at little in their lives, it can feel like the this stumble means heading to the back of the pack. Differentiating clinical competence from assessment success is very important.

What can we do as individuals to change this perception? Firstly, challenge our own preconceptions about what the journey to success looks like. There are always dead ends and wrong turns, in choosing training pathways or places of employment.

There are many doctors with happy, fulfilled lives and careers who took the opportunity to change tack from surgical training or physician training to pursue general practice or radiology. These stories aren’t talked about enough. We can help each other raise our sights, see the forest for the trees, and change paths to something that is more fulfilling.

We can advocate for complete training programs in rural and regional areas. We can advocate for linking training pathways to workforce requirements, as well as better production and availability of data on what the actual workforce looks like – so we might be able to see our place within it.

Being a doctor is a lot more than just practicing medicine. We are part of a profession, and it’s up to all of us to contribute to making our profession a more supportive place to learn and grow.

Prevention of breast cancer

Breast cancer prevention includes strategies that range from a change in lifestyle behaviours to alter modifiable risk factors, to the prophylactic use of chemoprevention or surgery — based on genetic predisposition or other factors that identify patients at high risk — and the treatment of pre-invasive lesions found by population mammographic screening.

The strategy for this narrative review was to search PubMed and the grey literature available on the internet for the most recent reviews and meta-analyses and for pivotal articles describing each preventive action, and to supplement those articles with others from the references of the reviews.

Many of the major risk factors for breast cancer cannot be changed. Breast cancer is more common in women than men by 100-fold.1 In women, reproductive factors, such as early menarche and late menopause — which increase the exposure of breast tissue to oestrogen and progesterone — also increase the risk of developing cancer.2 The incidence of breast cancer also increases with age, with 77% of breast cancer in Australian women occurring over the age of 50 years.1 A family history of first degree relatives (mother, sister or daughter), although associated with only one in nine breast cancers, almost doubles the risk compared with women who have unaffected relatives.3,4 An increase in breast density,5 which is associated with increased cancer risk, can also be a heritable trait, while inheriting mutated genes also increases this risk. For example, inheriting either BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutations, although they are only associated with less than 10% of breast cancers, increases the lifetime risk (to 75 years old) of breast cancer by 47% and 32% respectively.6

Lifestyle risk factors

The lifestyle factors that can be changed include diet, exercise, alcohol and tobacco consumption, the use of combination hormonal therapy, and the exposure of the breast to radiation. These have been estimated as being responsible for 40% of breast cancers. Also, an early age for a first full term pregnancy and breastfeeding have been associated with decreasing the risk of breast cancer. A recent meta-analysis has shown that these reproductive behaviours change the incidence of specific subtypes of breast cancer.7 Older age at first birth was associated with an increase in the luminal subtype of breast cancer, while having ever breastfed a baby reduced the risk of luminal and triple negative breast cancer, that is, breast cancer that does not have the receptors for oestrogen, progesterone or human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 (HER2).

Obesity

After reviewing the available studies, the World Cancer Research Fund (WCRF) has stated that there is convincing evidence for a link between obesity and being overweight, and post-menopausal breast cancer.8 In Australia, the proportion of breast cancers attributable to being overweight or obese is estimated to be 8%.9 A recent analysis of the observational study from the Women’s Health Initiative has shown that the duration of being overweight is associated with an increasing incidence of obesity-related cancers. Every 10-year increase in adult obesity duration is related to a 5% increase in the risk of post-menopausal breast cancer.10

Exercise has been found to decrease the risk of post-menopausal breast cancer independent of its impact on obesity.8 In pre-menopausal women, the average risk reduction is 30–40% and may be greatest in those of normal or low bodyweight.11

The risk of breast cancer decreases with increasing levels of physical activity.12 The question of how much exercise reduces this risk was recently reviewed by analysing 174 studies reported between 1980 and 2016, 35 of which were related to breast cancer. The findings were that it may require the equivalent of 15–20 hours of brisk walking each week or 6–8 hours of running to have an impact on reducing cancer, which is up to five times the previous recommendation of the World Health Organization.13 Compared with insufficiently active women, the risk of breast cancer decreased by 3% for low activity, 6% for moderate activity and 14% for high activity levels.13

The role of exercise in preventing breast cancer may be that exercise lowers hormone levels in pre-menopausal women and levels of insulin and insulin-like growth factor. It also improves the immune response and assists with weight maintenance.14

General dietary advice for a healthy lifestyle recommends limiting energy dense foods, red meat, salt and sugary drinks while eating more fresh fruit and vegetables. The evidence for specific dietary factors, such as fat intake relating to developing breast cancer is not definitive.15

Alcohol

The International Agency for Research on Cancer lists alcohol as a group 1 carcinogen, that is, a known cause of cancer. The WCRF reports that the evidence associating breast cancer with the consumption of alcohol is convincing.15,16 The cumulative amount of alcohol consumed is associated with an increased risk of breast cancer, which is not linear as the dose response curve becomes steeper at higher alcohol intakes, indicating greater risk with heavier alcohol intake.17

The National Health and Medical Research Council recommends that a low risk of alcohol consumption for healthy adults is two standard drinks (equivalent of 10 g or 12.5 ml pure alcohol per drink). At that level, the lifetime risk of dying from an alcohol-related disease is less than 0.4 per 100 people.18,19 In Australia, the proportion of breast cancers attributable to alcohol has been estimated to be 5.8%.19

The main mechanism for the carcinogenicity of alcohol is that its main metabolite, acetaldehyde, is carcinogenic.20

Hormone use

Although individual women may benefit from hormone replacement therapy (HRT) to manage symptoms of menopause, population studies show that the use of combined hormones with both oestrogen and progesterone is associated with an increased risk of breast cancer.21 The Women’s Health Study quantified the relative risk of breast cancer with HRT use as 1.37, while the Million Women Study found the relative risk to be 2.14.22,23 This risk increases with the duration of HRT (usually after the first 3 years), but seems limited to the period in which the hormones are taken, and it returns to the levels of those who have not taken HRT by 5 years after ceasing treatment.24 The risk is also higher in women who start HRT close to the onset of menopause rather than later.25 When HRT use declined in some countries, because of publicity about the link with breast cancer, the breast cancer incidence fell.26 If oestrogens are used alone, most studies report no increased risk of breast cancer.27

There is some evidence from a review of 50 studies in 1996 that longer term users of oral contraceptives have a small increase in the risk of breast cancer, which returns to baseline by 10 years after ceasing them.28

Although this should no longer occur, in utero exposure to diethylstilboestrol has an increased breast cancer risk.29

Tobacco

There has been no consistent association between tobacco smoking and breast cancer. The results are confounded by concomitant alcohol use. A recent meta-analysis showed that there was a 24% increase in the likelihood of developing cancer only in women who also currently or previously drank alcohol if they smoked as compared with non-smokers. The greatest risk was in those who commenced smoking before their first menstrual period, who had a 61% increased risk. Those who started to smoke tobacco at least 11 years before their initial full term pregnancy had a 45% higher risk of developing breast cancer.30

Ionising radiation

Ionising radiation is radiation with sufficient energy to break electrons off atoms and disrupt the DNA in cells. Exposure can be to large doses, such as was observed after nuclear explosions or accidents, or when receiving radiation therapy. Small doses of radiation, such as may be experienced with multiple computed tomography (CT) scans or mammograms, where the exposure is cumulative may be problematic, but in some situations have been found to stimulate an immune response.31 Although the overall risk of breast cancer following exposure to ionising radiation is low, it is greater if the exposure occurs at a younger age. It is also greater if women already have gene mutations that increase their risk of cancer and it may be additive to the impact of exogenous oestrogens on the risk of developing breast cancer.32,33 The implication of these findings is that benefits of diagnostic imaging by using x-rays or CT scans should be carefully assessed against this risk, particularly in younger patients, and this may include consideration of alternative tests such as ultrasound or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scans. Reassessing the indications for therapeutic radiation and, where possible, the better targeting of therapeutic radiation therapy to reduce the exposure of the breast, will also help reduce this risk.

Occupation

Studies examining exposure to ionising radiation among radiological technologists demonstrated an elevated risk of mortality from breast cancer for those who operated equipment before 1950 and if they started working at younger ages.34,35 In a recent review, airline workers have been associated with an increased risk of breast cancer, which may be partly due to cosmic radiation exposure.36 Nightshift work has also been associated with an increased mortality from breast cancer as reported in a recent meta-analysis of prospective cohort studies.37 Other occupational exposures, such as to pesticides, solvents and heavy metals, have insufficient evidence to characterise their association with breast cancer.38

Chemoprevention

For women at high risk of breast cancer, taking medication may reduce their chances of developing breast cancer, but there is no survival advantage yet documented.

Selective oestrogen receptor modulators

Tamoxifen is one of a series of selective oestrogen receptor modulators (SERMs) which reduce the impact of oestrogen on the breast. High risk includes women with a strong family history of breast cancer or who have a biopsy that shows pre-invasive cancer pathology, such as lobular carcinoma in situ (LCIS), atypical ductal hyperplasia or atypical lobular hyperplasia. Those who will benefit from tamoxifen are women over 35 years with a risk of breast cancer of more than 0.66% on the Gail model.39 The Gail model is a risk assessment tool which scores demographic risk factors, such as age and ethnicity, along with histological features, such as positive ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS) and LCIS, family history and menstrual history.39 The side effects of tamoxifen include hot flushes, night sweats, vaginal dryness and discharge, and cataracts. Rarer but more serious toxicities are thromboembolic events which cause strokes, deep venous thrombosis and pulmonary emboli, and the development of endometrial and uterine cancer.

Raloxifene is a second generation SERM that is not quite as effective as tamoxifen, but does not increase the risk of uterine cancer and also helps prevent osteoporosis. It is often used for post-menopausal women at high risk.

A meta-analysis of 10-year data from nine randomised trials of SERMs as chemopreventive agents in women at high risk of breast cancer showed a 38% reduction in overall breast cancer incidence and a 51% reduction for oestrogen receptor positive cancers.40 This preventive effect of tamoxifen can last for 20 years.41 Raloxifene’s impact on prevention does not last as long and has about 76% the efficacy of tamoxifen.

Third generation SERMs, such as lasofoxifene and arzoxifine, which also treat reduced bone mineral density, have been trialled with reduction in the development of invasive breast cancer, but these drugs are not yet approved for use.

Despite the impressive results of chemoprevention of SERMs in women at high risk, the uptake of this preventive strategy has been poor. A meta-analysis of 36 studies of participation in chemoprevention showed the uptake to be 16.3%, higher in trial settings (25.2%) than in non-trial settings (8.7%).42 A higher uptake was associated with older age, having an abnormal biopsy result, higher risk, fewer concerns about side effects and having a clinician recommend it.42

Aromatase inhibitors

Aromatase inhibitors, such as anastrazole, letrozole and exemestane, are used to treat post-menopausal women who have oestrogen receptor positive breast cancer. Although they may have side effects, such as hot flushes, vaginal dryness, joint and muscle pains and fatigue, and may increase the risk of osteoporosis, they are not associated with thromboembolic phenomena or uterine cancer like the SERMs.42 They have been tested as chemopreventive agents for oestrogen receptor positive tumours in post-menopausal women and had sufficient activity to be tested against tamoxifen.43,44

Anti-human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 drugs

Small trials have been mounted to test trastuzumab in patients with human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 (HER2)-positive DCIS. Lapatanib is also being tested pre-operatively in patients with HER2-positive DCIS to determine whether its use prevents invasive cancer.42

Aspirin

Aspirin has been associated with chemoprevention in patients with high risk colorectal cancer. To explore the association between aspirin use and post-menopausal breast cancer, women with no history of breast cancer were followed and divided into those who used aspirin and those who did not. The use of aspirin decreased the breast cancer incidence in women with a family history of breast cancer or a history of benign breast disease.45 Further studies are required.

Mammographic screening

In Australia, population mammographic screening for early detection of breast cancer is provided for the target group of women aged between 50 to 74 years. It has been shown to reduce mortality from breast cancer. However, because breasts can develop pre-invasive lesions before developing invasive cancer, a mammogram is important for preventing invasive breast cancer in addition to early diagnosis of invasive disease when it can still be cured, thereby reducing the mortality from breast cancer. As an example, in 2010 in the United Kingdom, mammographic screening diagnosed 125.7 cancers per 100 000 woman years, whereas the pre-invasive lesions of DCIS and LCIS were detected at a rate of 18 per 100 000.46

Screening by mammography or MRI may be recommended in younger women with a high risk of developing breast cancer, such as women with BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutations or multiple close relatives with breast cancer, particularly if they developed cancer at a younger age.

The other feature that mammography can assess is breast density. Differences in density relate to the different proportions of the dense fibro-glandular tissue to the less dense adipose tissue, which causes a different appearance on mammography measured by less or more radiolucency. Increased breast density has been shown to be a risk factor for non-familial breast cancer. Although higher density may make cancers more difficult to see, and increased breast density has been related to other risk factors — such as family history, not having had children and exogenous hormone use — breast density is nonetheless an independent risk factor. A higher proportion of dense tissue has been associated with a four to five times higher risk of developing breast cancer.5 Moreover, the cancers diagnosed in women with increased breast density are often larger, higher grade and with more lymphatic invasion and lymph nodes and higher stage, but this does not increase the risk of death when accounting for these factors.47 The importance of assessing such risk factors is that it may identify candidates for chemoprevention to reduce the chances of developing breast cancer.

Genetic testing

When the genes BRCA1 and BRCA2, which code for tumour suppressor proteins, are mutated, the lifetime risk of breast, ovary and other cancers is increased. This is the case in up to 25% of inherited breast cancers and 10% of breast cancers overall.48 It is estimated that BRCA1 carriers have a 55–65% chance of developing breast cancer by the age of 70 years and BRCA2 carriers have a 45% chance of developing breast cancer by 70 years, depending on their other risk factors.49

Genetic counsellors usually determine who needs to be tested based on aspects of their family history, such as first degree relatives with breast cancer diagnosed before 50 years, multiple breast primaries of bilateral cancers, male breast cancer, ovarian cancer, or Ashkenazi Jewish ethnicity.

There are other genes associated with an increased risk of breast cancer.48 These are found in inherited disorders such as Li–Fraumeni syndrome and Fanconi anaemia. The PALB2 gene associated with Fanconi anaemia codes for a tumour suppressor gene which produces a protein that interacts with the proteins produced by BRCA1 and BRCA2 to help with DNA strand break repairs.50

Combining modifiable risk factors with non-modifiable factors, including single nucleotide polymorphisms and family history, is being explored to develop a more accurate model for predicting the absolute risk of women developing breast cancer.51 This will enable the identification of people who will benefit from risk reduction strategies to prevent breast cancer. These may include screening at an earlier age, which can introduce other imaging techniques such as MRI. Chemoprevention can also be considered in these higher risk groups, and prophylactic surgery which removes as much of the breast tissue as possible becomes a further option.

Surgical prevention of breast cancer

For BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutations, which carry an increased risk of breast and ovarian cancer, bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy reduces the risk of ovarian and fallopian tube cancer and halves the risk of breast cancer. The mutation carriers will also benefit from bilateral prophylactic mastectomy, which reduces their breast cancer risk by up to 95%, more so than non-mutation carriers who may also be offered the procedure because of high risk.51,52 A more controversial surgical area is contralateral mastectomy after the diagnosis of cancer in the other breast. This has not been associated with increased survival.53 Reconstructive surgeries can restore the symmetry of the breasts as an alternative to contralateral mastectomy if that is the motivation for requesting it.54

As with chemoprevention, uptake of these surgical preventive strategies is lower or later than recommended.55 The risks and benefits of these strategies must be assessed for each individual.

Conclusions

Preventing breast cancer begins with identifying those at higher risk because of their pattern of genetic mutations; demographic features, such as age, sex and ethnicity; reproductive and hormonal factors; family history of breast cancer; past history of benign breast disease; or lifestyle behaviours. Mammographic screening can detect pre-invasive lesions that can be treated. Modifiable lifestyle behaviours include increasing exercise and dietary modification to prevent obesity, moderating alcohol intake, not smoking, balancing the risks when deciding on taking exogenous hormones, and reducing exposure to radiation and other occupational exposures. In addition, patients at high risk may benefit from chemoprevention with tamoxifen and other hormones, prophylactic bilateral surgical mastectomies, or salpingo-oophorectomies.

Stating best practice in breast cancer care

Although survival for women with breast cancer in Australia is among the highest in the world, there is evidence that not all patients are receiving the most appropriate care.

Cancer Australia has brought together evidence and expertise to support improved and informed practice in breast cancer. The Cancer Australia Statement — influencing best practice in breast cancer is based on the best available evidence and is supported by expert clinical and consumer advice. The statement represents agreed priority areas which, if implemented, will support effective, patient-centred breast cancer care and reduce unwarranted variations in practice.

The statement aims to encourage health professionals to reflect on their clinical practice to ensure that it is aligned with best practice. It also aims to encourage consumers to start conversations with their medical teams to improve their cancer experience and outcomes.

There are 12 practices in the breast cancer statement, from diagnosis across the continuum of care. The practices are identified as either appropriate or not appropriate.

A practice is appropriate if it is beneficial for patients, effective (based on valid evidence, including evidence of benefit), efficient (cost-effective) and equitable.

A practice is not appropriate if it is not consistent with the evidence, may cause potential harm or provides little benefit to patients.

The practices were chosen with the collaboration, participation and engagement of relevant clinical colleges, cancer and consumer organisations. The statement is intended to complement relevant clinical practice guidelines.

Supporting materials have been developed for the statement, including information on the value to patients, evidence base and references for each practice.

More information about the statement and recommended practices is available at canceraustralia.gov.au/statement.

Private insurers being brought to account

The AMA’s activities over several years to shed light on the egregious behaviour of certain private health insurers is now bearing fruit.

The Australian Competition and Consumer Commission (ACCC), the Commonwealth Ombudsman and the Federal Government are now taking action to curb unacceptable practices and shift the focus onto consumer needs, informed by AMA advice and submissions.

As part of its work in this area, the AMA recently made a submission to the Government’s review of private health insurance policy. Our submission called for the Government to abolish ‘junk’ policies; prevent insurers from arbitrarily introducing exclusions in policies and benefit payment schedules without prior advice; and prohibit insurers from encouraging consumers to purchase a product, or downgrade their cover to a level that is inappropriate to their health care needs.

In addition, the AMA’s inaugural AMA Private Health Insurance Report Card issued in February this year sent a clear message that consumers could not take at face value information provided by their health insurer. We warned consumers to avoid ‘junk policies’ – those that provide cover only for treatment in public hospitals – and to ensure they clearly understood the level of benefits paid by their insurer and likely out-of-pocket costs.

In response, the Government has now announced that it will eliminate junk policies as a part of its program of private health insurance reforms.

The Government also intends to create a three-tiered system of policies that will allow consumers to more easily choose a product that is right for them. It will mandate minimum levels of cover for policies, and develop standardised terminology for medical procedures.

These proposals will require detailed consideration to ensure an appropriate balance between private and public health care is maintained. This work will keep the Medical Practice Committee busy this year.

The Government has also responded to our complaints that the operations of third party comparator sites for private health insurance are not transparent; ‘comparisons of best value’ exclude some policies and commissions are kept secret. The Government will require third party comparator sites to publish commissions they receive, similar to the requirements for other financial services.

The Commonwealth Ombudsman is also investigating those insurers who are insisting on seeking ‘pre-approvals’ for plastic and reconstructive procedures. Many of our surgeon members have been affected by this practice in which insurers require private hospitals to get surgeons to fill in and ‘certify’ a form providing clinical details of the procedure and the reasons why it is necessary.

While insurers continue to claim that this process is not compulsory and does not constitute a ‘preapproval’, we understand that patients, hospitals and medical practitioners are being told that if forms are not submitted, benefits will not be paid.

In direct response to AMA concerns, the Department of Health wrote to all insurers in 2015 reminding them that, under law, they must pay benefits for a hospital treatment when an insured member undergoes a procedure for which a Medicare benefit is payable, and which is covered by their health insurance product.

Clearly this advice has been ignored, but the Ombudsman’s investigation will hopefully put a stop to this practice.

Finally, the ACCC is taking legal action against Medibank Private for allegedly misleading consumers – specifically, failing to give notice to members on its decision to limit benefits paid for in-hospital pathology and radiology services.

As mentioned earlier, we raised the issue of arbitrary changes to policies and benefits in our submission to the Government’s private health insurance review last year, but we also brought this to the attention of the ACCC in our 2016 submission concerning insurer activities designed to erode the value of private health insurance cover and maximise insurer profits.

Commenting on its legal action, the ACCC said: “Consumers are entitled to expect that they will be informed in advance of important changes to their private health insurance cover, as these changes can have significant financial consequences”.

The AMA wholeheartedly agrees.

Your Family Doctor: Invaluable to your health

AMA Family Doctor Week, 24 – 30 July 2016

The AMA used this year’s Family Doctor Week to not only celebrate the hard work and dedication of Australia’s 30,000 GPs, but to put the re-elected Coalition Government on notice that changes in health care policy are urgently needed.

The traditional National Press Club address has been moved to August to allow for continued campaigning against the Medicare rebate freeze, cuts to public hospital funding, and cuts to bulk billing incentives for pathology and radiology.

Media outlets around the country, including the national WIN network of regional television stations, picked up on the message that GPs are the most cost-effective sector of the health system and need support.

AMA President, Dr Michael Gannon, said that the personalised care and preventive health advice provided by family doctors helps to keep people out of hospitals, and keep health costs down.

“Australian GPs provide the community with more than 137 million consultations, treat more than 11 million people with chronic disease, and dedicate more than 33 million hours tending to patients each year,” Dr Gannon said.

“Nearly 90 per cent of Australians have a regular GP, and enjoy better health because of that ongoing trusted relationship.”

The AMA used the week to outline a series of proposals for improving the health of Australians while also delivering savings to the Government.

The Pharmacist in General Practice Incentive Program (PGPIP) proposal would integrate non-dispensing pharmacists into GP-led primary care teams, allowing pharmacists to assist with medication management, provide patient education on their medications, and support GP prescribing with advice on medication interactions and newly available medications.

“Evidence shows that the AMA plan would reduce unnecessary hospitalisations from adverse drug events, improve prescribing and use of medicine, and governments would save more than $500 million,” Dr Gannon said.

“When the Government is looking to make significant savings to the Budget bottom line, the AMA’s proposal delivers value without compromising patient care or harming the health sector.”

Independent analysis from Deloitte Access Economics identified that the proposal would deliver $1.56 in savings for every dollar invested in it.

The AMA also stepped up the pressure for more appropriate funding for the Government’s trial of the Health Care Home model of care for patients with chronic disease.

In March, the Government committed $21 million to allow about 65,000 Australians to participate in initial two-year trials in up to 200 medical practices from 1 July 2017. However, the funding is not directed at services for patients.

“GPs are managing more chronic disease, but they are under substantial financial pressure due to the Medicare freeze and a range of other funding cuts,” Dr Gannon said.

“GPs cannot afford to deliver enhanced care to patients with no extra support. If the funding model is not right, GPs will not engage with the trial, and the model will struggle to succeed.”

With chronic conditions accounting for approximately 85 per cent of the total burden of disease in Australasia and 83 per cent of premature deaths in Australia, it was vital that Australians could turn to their family doctor for advice, Dr Gannon said.

“The Government uses concerns about the sustainability of the health system to justify funding cuts, but instead of making short-sighted and short-term savings, it should invest in preventing disease in the first place,” he said.

Family doctors in rural and regional communities, in particular, needed more support.

The AMA called on the Government to rethink its approach to prevocational training in general practice, and to revamp and expand its infrastructure grants program for rural and regional practices.

Maria Hawthorne

The clinical utility of new cardiac imaging modalities in Australasian clinical practice

Cardiac imaging is a rapidly evolving field, with improvements in the diagnostic capabilities of non-invasive cardiac assessment. In this article, we seek to introduce family physicians to the two main emerging technologies in cardiac imaging: computed tomography coronary angiography (CTCA) to evaluate chest symptoms consistent with ischaemia and exclude coronary artery disease; and cardiovascular magnetic resonance (CMR) imaging for evaluating cardiac morphology, function and presence of scar. These modalities are now in routine clinical practice for cardiologists in Australia and New Zealand. We provide a practical summary of the indications, clinical utility and limitations of these modern techniques to help familiarise clinicians with the use of these modalities in day-to-day practice. The clinical vignettes presented are cases that may be encountered in clinical practice. We searched the PubMed database to identify original papers and review articles from 2008 to 2016, as well as specialist society publications and guidelines (Society of Cardiovascular Computed Tomography, Society for Cardiovascular Magnetic Resonance, Cardiac Society of Australia and New Zealand, and Australian and New Zealand Working Group for Cardiovascular Magnetic Resonance), to formulate an evidence-based overview of new cardiac imaging techniques, as applied to clinical practice.

Part 1: Computed tomography coronary angiography for clinicians

CTCA is a non-invasive coronary angiogram, using electrocardiogram (ECG)-gated CT. The accuracy of CTCA has been well established in three large multicentre studies, with a negative predictive value approaching 100%, making it an excellent “rule out” test.1 This means that a normal CTCA showing no coronary plaque or stenosis accurately correlates to absence of disease on invasive angiography. Prognostic data have shown that a negative CTCA has very low event rate (< 1%), whereas increasing levels of disease seen on CTCA are associated with increasing risk of myocardial infarction and death over 5 years for both men and women.2

CTCA has been formally tested in randomised trials of chest pain in the emergency department, showing more rapid discharge and decreased health care costs, including in the Australian health system.3,4

The radiation dose for CTCA has decreased dramatically in recent years, with current generation scanners able to image the entire heart and coronary arteries for 2–3 mSv (equivalent to annual background radiation), and < 1 mSv in appropriate patients (similar to a mammogram). Thus, CTCA is gaining traction in clinical practice to rule out coronary artery disease (CAD) in a variety of clinical situations.

The primary use for CTCA is to exclude significant coronary artery stenosis in patients with symptoms consistent with coronary ischaemia due to potential stenotic CAD (harnessing the near 100% negative predictive value of CTCA). Application of the test in this manner is appropriate for patients with chest pain syndromes, with angina equivalent symptoms (eg, dyspnoea), to exclude graft stenosis in symptomatic patients after coronary artery bypass surgery, and also for patients with ongoing symptoms despite negative results from functional tests such as nuclear or echocardiography stress tests (as functional tests may return false-negative results). The Society of Cardiovascular Computed Tomography has published Appropriate Use Criteria,5 and the Cardiac Society of Australia and New Zealand has produced guidelines on non-invasive coronary imaging (Box 1).6

Clinical vignette 1: A 55-year-old woman presents to her general practitioner with dyspnoea on exertion, and risk factors of obesity and hypertension. A nuclear single-photon emission computed tomography myocardial perfusion scan is reported as positive for “mild apical ischaemia”. Computed tomography coronary angiography (CTCA) is performed to exclude significant coronary artery disease, demonstrating no significant stenosis in the major epicardial coronaries (left anterior descending, left circumflex or right coronary artery), but mild diffuse coronary atherosclerosis is present (with a calcium score of 370 Agatston units). She is commenced on medical therapy of aspirin and a statin, and is reassured that she does not have a stenosis requiring stent or bypass surgery, and that her chest symptoms are not due to coronary artery disease.

CTCA showing “clean” coronary arteries with no plaque or stenosis.

In Australia, Medicare reimbursement is available via specialist referral for three indications:

-

chest symptoms consistent with coronary ischaemia in low to intermediate risk patients;

-

evaluation of suspected coronary anomaly or fistula; or;

-

exclusion of CAD before heart transplant or valve surgery (non-coronary cardiac surgery).

Medicare-reimbursed indications do not cover asymptomatic patients with a strong family history of coronary artery disease (in which case, a coronary calcium score may suffice).7 When used appropriately, CTCA reduces the need for invasive coronary angiography, which is about five times more expensive, as a consequence of the reduced need for hospital admissions and different Medicare Benefits Schedule charges. Data suggest that use of CTCA is cost-effective and reduces downstream testing.8

Importantly, CTCA is not appropriate in patients with typical angina (defined as “constricting discomfort in the chest, which is precipitated by physical exertion, and relieved by rest or GTN”9) who have a high pre-test probability of obstructive disease and should proceed directly to invasive coronary angiography.

Evaluation after coronary artery stenting is limited to large diameter stents (> 3 mm) in proximal arteries and, in general, functional testing remains the clinical standard for reassessment of patients with known CAD.5 Conversely, assessment of graft patency following coronary artery bypass surgery can be well assessed by CTCA, without the risks of stroke or graft dissection from invasive engagement of the grafts during catheter angiography.5

The main weakness of CTCA is its modest positive predictive value, which varies from 60% to 90% depending on the prevalence of disease and the study. In clinical practice, this generally means that although coronary disease seen on CTCA is real, the percentage of stenosis generally appears more severe on CTCA compared with invasive coronary angiography. On the other hand, CTCA can visualise eccentric coronary plaques with positive vessel wall remodelling, which may be missed on invasive angiography (which only images the coronary lumen, and not the vessel wall itself).

An important factor in CTCA is heart rate control, which remains essential for good quality CTCA imaging. Ideal heart rates are in the 50–60 beats per minute range for optimal imaging, requiring pre-medication with β-blockers and/or ivabradine. Heart rate control is proportional to radiation dose, therefore low dose studies require a slow and steady heart rate. This improves the diagnostic accuracy of CTCA, but negative chronotropic medications may not be suitable for all patient groups, and atrial fibrillation remains a challenge. Newer high resolution and dual source scanners are able to image at higher heart rates, with algorithms to reconstruct cardiac motion, and are becoming more widely available.

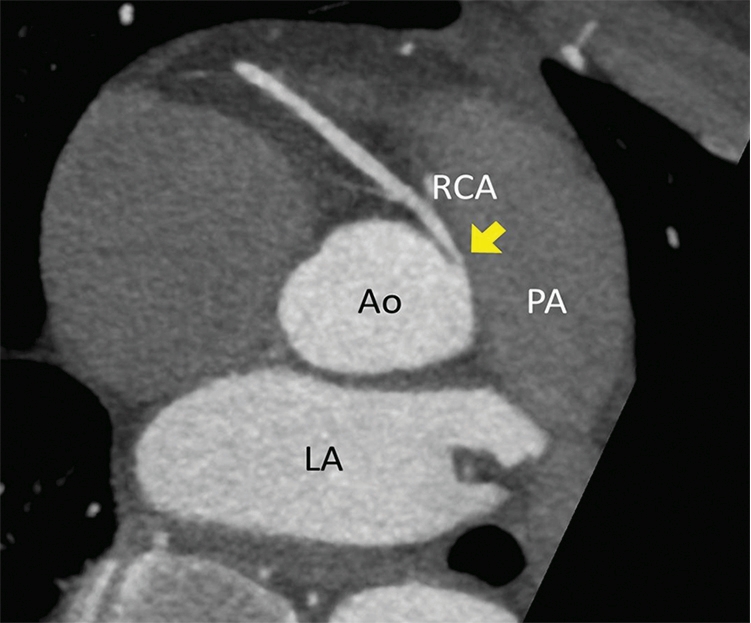

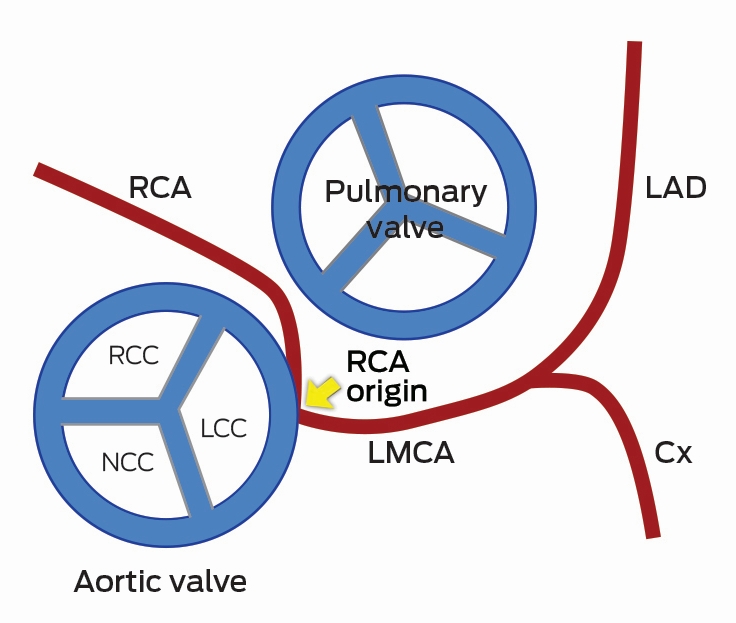

Clinical vignette 2: A 38-year-old man presents to an emergency department with atypical central chest pain. Serial troponins are negative, and a 12-lead electrocardiogram shows non-specific T wave changes. He has ongoing pain, is not deemed suitable for an “accelerated diagnostic protocol” pathway, and early computed tomography coronary angiography (CTCA) is performed after 100 mg oral metoprolol with 10 mg ivabradine, to achieve a heart rate of 59 beats per minute, allowing a low dose (< 1 mSv) scan. CTCA shows a normal left coronary system, but an anomalous right coronary artery origin arising from the contralateral cusp, with an interarterial course and a slit-like origin.6 This is a potentially life-threatening anomaly due to potential compression between the aorta and pulmonary artery resulting in sudden death;10 however, this may not have been diagnosed on functional testing (eg, single-photon emission computed tomography). Cardiac CT is the reference test for the assessment of coronary anomalies and coronary fistulae.6

CTCA axial view showing the RCA origin adjacent to the left main sinus and with an interarterial course between the aorta and pulmonary artery (arrow). Ao = aorta. Cx = circumflex. LA = left atrium. LAD = left anterior descending artery. LCC = left coronary cusp. LMCA = left main coronary artery. NCC = non-coronary cusp. PA = pulmonary artery. RCA = right coronary artery. RCC = right coronary cusp.

Recent data from the PROMISE trial in 10 000 patients showed equivalence of a CTCA versus functional testing strategy in symptomatic patients, but with a reduced rate of “normal” invasive angiograms and decreased downstream testing in the CTCA group.11 Further, the SCOT-HEART trial recently demonstrated that adding CTCA to standard care reduced the need for additional stress testing, and was associated with a 38% reduction in fatal and non-fatal myocardial infarction.12

Future directions for CTCA

Rapid technological advancement in both CT hardware and post-processing reconstruction software algorithms are leading to further improvements in spatial and temporal resolution while minimising radiation exposure. CTCA has the ability to detect high risk vulnerable plaques,6,13 and statin therapy may help alter the natural history of atherosclerosis as imaged by CTCA.13 New developments enable functional assessment of a lesion on CTCA, allowing assessment of lesion-specific ischaemia at the same time as evaluating coronary anatomy. Adenosine stress perfusion cardiac CT allows functional assessment of myocardial perfusion in a similar manner to nuclear single-photon emission computed tomography (SPECT), and can be performed at the same time as CTCA with minimal additional radiation.14 Fractional flow reserve can be derived from static CTCA datasets, using computational fluid dynamics, and has been compared favourably with invasive haemodynamic assessment of fractional flow reserve during invasive coronary angiography.15 Overall, CTCA is a very useful tool to non-invasively assess the coronary arteries, with prognostic data now available to support its routine use in clinical practice.

Part 2: Cardiovascular magnetic resonance imaging for clinicians

CMR is a specialised form of magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), which employs specific MRI techniques with ECG gating to capture high resolution images of the heart and cardiac motion, in any imaging plane, without radiation.16 CMR is like a “super-echocardiogram” to assess heart function, but has the additional ability to quantitate vascular flow, myocardial oedema, cardiac perfusion, viability, and the presence of infiltrate or scar using gadolinium-based contrast agents. CMR improves diagnosis and risk stratification, predicts prognosis, and guides treatment decisions in many cardiac disorders.

Left and right ventricular function

Accurate quantitation of left and right ventricular function are essential to making decisions in clinical medicine, from commencement of drug therapy to implantation of costly devices such as automatic defibrillators. CMR is the gold standard for measurements of left ventricular mass, volume and ejection fraction and assessing the presence of regional wall motion abnormalities,17,18 and it is more reproducible than echocardiography.19

CMR offers particular advantages for conditions affecting the right ventricle, which is particularly difficult to assess using echocardiography. Assessment of right ventricular volume and wall motion by CMR are assigned as major criteria in the diagnosis of arrythmogenic right ventricular dysplasia/cardiomyopathy (ARVD/C), a genetic condition resulting in arrhythmias and sudden death.20 Right ventricular function is important in patients in pulmonary hypertension and with adult congenital heart disease,21 for which CMR is critical to decision making (eg, timing of surgery, replacement of cardiac valves). In patients with dilated right hearts, CMR is useful to detect the underlying causes, which may not be apparent on echocardiography (such as partial anomalous pulmonary venous drainage, or ARVD/C).

Viability and scar imaging

CMR can be used to confirm the diagnosis of myocardial infarction and assess viability before stenting or coronary artery bypass surgery, using gadolinium contrast agents to image scar tissue.

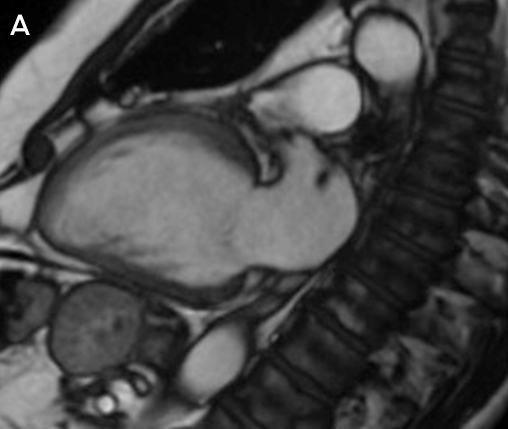

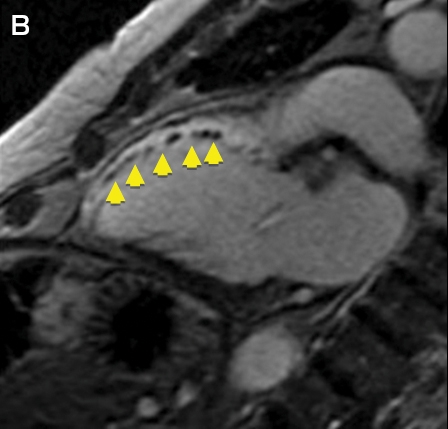

Clinical vignette 3: A 74-year-old man with a late-presentation ST-elevation myocardial infarction is shown to have an occluded left anterior descending artery during coronary angiography. Echocardiography shows an ejection fraction of 40%. Cardiovascular magnetic resonance (CMR) demonstrates that the anterior wall is akinetic, with full thickness infarction and no residual viable myocardium. Based on this information, he does not undergo stenting or coronary artery bypass graft surgery and is treated medically with heart failure therapy.

CMR imaging: two-chamber view showing a dilated left ventricle with akinetic anterior wall (A), and post-contrast imaging showing full thickness infarction of the entire anterior wall with no residual viable myocardium (B, arrows).

Infiltrative disorders traditionally requiring cardiac biopsy

CMR is a useful tool to diagnose infiltrative disorders which have traditionally required invasive cardiac biopsy, such as cardiac sarcoidosis, cardiac amyloidosis, and detection of fibrosis in hypertrophic cardiomyopathy.22–25 The EuroCMR registry of over 27 000 patients showed that using CMR improves diagnosis and changes clinical management in patients with cardiac conditions.26 Common indications and contraindications for CMR are shown in Box 2.27

Clinical vignette 4: A 26-year-old woman with palpitations has an echocardiogram showing a dilated right heart but with intact atrial and ventricular septum; the cause for right heart dilation was unclear. CMR showed a right ventricular volume index of 143 mL/m2 (moderate to severely dilated), and confirmed a diagnosis of partial anomalous pulmonary venous drainage of the right veins to the superior vena cava (significant intracardiac shunt: Qp:Qs, 2:1). She underwent minimally invasive cardiac surgical repair, with normalisation of right heart size at follow-up.

Myocardial fibrosis and iron overload

CMR is a “non-invasive microscope” of the heart, with techniques such as quantitative T1 mapping allowing non-invasive measurement of fibrosis and extracellular volume fraction.28 Cardiac iron overload occurs in haemochromatosis and thalassaemia, and is a significant cause of morbidity and mortality in these conditions.29 In the past, cardiac biopsy was the only means to assess myocardial iron overload. However, using iron-sensitive T2* imaging, CMR has been validated to quantitatively and non-invasively measure myocardial iron stores. Australian guidelines exist for using CMR to assess for iron overload, with T2* values of > 20 ms being normal, < 10–20 ms indicating moderate iron overload, and values of < 10 ms indicating severe iron overload warranting consideration for chelation therapy.29

Ventricular thrombus

CMR is the gold standard test for detection of ventricular thrombus after myocardial infarction and is superior to echocardiography, including microsphere contrast echocardiography (Box 3).30

Valvular dysfunction

Quantitation of valvular regurgitation is more reproducible by CMR than by echocardiography,31 and is particularly useful in assessing aortic and pulmonary regurgitation, which are difficult to quantitate echocardiographically. CMR has been allocated a Class I indication for use in patients with moderate or severe valve disorders and suboptimal or equivocal echocardiographic evaluation (Class I, Level of evidence B).31,32 CMR is validated for the direct planimetric assessment of aortic stenosis, which can be performed using steady-state free precession cine imaging without requiring contrast (this may be useful for patients with renal impairment, such as those being assessed for transcatheter aortic valve implantation).33 CMR is also superior to echocardiography for the assessment of mitral regurgitation after percutaneous mitral valve repair.34 In clinical practice, CMR is useful when a valve lesion is of indeterminate or equivocal severity by echocardiography, when quality echocardiographic images are suboptimal (eg, due to limited acoustic windows), or when the “downstream effect” of a lesion needs further quantitation, such as left ventricular dilation in severe but asymptomatic valve regurgitation.

Stress perfusion CMR

Stress perfusion testing can be performed with CMR and has superior spatial resolution to nuclear SPECT imaging without the exposure to radiation. A large, prospective comparative efficacy trial recently demonstrated that stress perfusion CMR was superior to SPECT for the diagnosis of myocardial ischaemia.35 CMR can also provide information on viability (scar) and the coronary arteries in the same non-invasive test, making it a “one-stop shop” that is increasingly being adopted in Europe and the United Kingdom for stress imaging in cardiology practice.26

Limitations of CMR

The main limitation of CMR is availability, with the technique mainly confined to reference expert centres owing to its complexity and the degree of training required to perform and report CMR. Guidelines exist from the Society of Cardiovascular Magnetic Resonance on the performance and reporting of CMR, and specific Australian and New Zealand guidelines are currently being formulated. The second major limitation is the lack of specific Medicare reimbursement for CMR. At present, two applications are before the Medical Services Advisory Committee (MSAC): one for stress perfusion/viability imaging and one for assessment of cardiomyopathies in patients with abnormal baseline echocardiography (MSAC application 1393: http://www.msac.gov.au/internet/msac/publishing.nsf/Content/1393-public).

While CMR provides superior diagnostic information than echocardiography in virtually all cardiac disorders, it is more resource intensive, time consuming and currently less available than echocardiography. CMR should be targeted for patients in whom echocardiography is inconclusive or non-diagnostic, or in specific circumstances where CMR is more appropriate than echocardiography (such as complex congenital heart disease, or the use of stress perfusion when it is clinically appropriate to assess ventricular function, viability and ischaemia in a single test).

Relative contraindications are present in patients with arrhythmias that affect ECG gating, claustrophobia, implantable devices, and severe renal impairment (if contrast imaging is required). Most modern pacemaker systems are MRI conditional at a field strength of 1.5 T, but are not compatible with 3 T systems.

Conclusions

Cardiac imaging is a rapidly evolving field, with improvements in the diagnostic capabilities of non-invasive cardiac assessment. CTCA is useful to exclude coronary artery disease non-invasively. CMR is useful to accurately quantitate left ventricular and right ventricular function and investigate cardiomyopathies, or patients with congenital heart disease. CTCA and CMR and are becoming routine clinical practice for cardiologists in Australia and New Zealand, with increasing use in both hospital and outpatient settings. General practitioners and general physicians should be familiar with the basic indications, clinical utility and limitations of these modern techniques to assist in their appropriate use and interpretation in day-to-day practice.

Box 1 –

Appropriate indications for computed tomography coronary angiography endorsed by the Cardiac Society of Australia and New Zealand6

- Chest pain with low to intermediate pre-test probability of coronary artery disease (CAD)

- Chest pain with uninterpretable or equivocal stress test or imaging results

- Normal stress test results but continued or worsening symptoms

- Suspected coronary or great vessel anomalies

- Evaluation of coronary artery bypass grafts (with symptoms)

- Exclude coronary artery disease in new onset left bundle branch block or heart failure

Box 2 –

Common indications and contraindications for cardiovascular magnetic resonance imaging25

Common indications

- Myocardial viability (ischaemic cardiomyopathies)

- Accurate assessment of left ventricular ejection fraction; eg, before device implantation (implantable cardioverter defibrillator and cardiac resynchronisation therapy)

- Detection of interventricular thrombus

- Interstitial fibrosis (dilated and infiltrative cardiomyopathies)

- Congenital heart disease

- Cardiac mass

- Right ventricular quantification

- Evaluation for arrythmogenic right ventricular dysplasia/cardiomyopathy

- Post cardiac transplantation surveillance

- Constrictive pericarditis

- Quantification of valvular dysfunction

- Aortic and vascular measurement

- Iron overload quantification (T2*)

Contraindications

- Absolute

- Non-magnetic resonance compatible implantable devices

- Severe claustrophobia

- Relative

- Magnetic resonance imaging conditional pacemakers (only 1.5 T field strength)

- Arrythmias that affect electrocardiogram gating (atrial fibrillation and ectopy)

- Severe renal impairment (risk of nephrogenic systemic fibrosis)

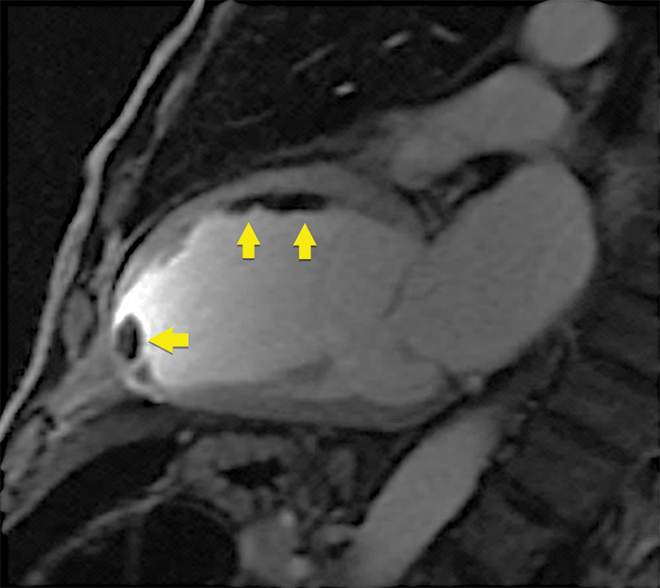

Box 3 –

Early post-contrast cardiovascular magnetic resonance image showing multiple thrombi in the mid-anterior wall and left ventricular apex (arrows)

Note: on microsphere contrast echocardiography, only the apical thrombus was seen; the thrombi adherent to the mid-anterior wall were not observed.

more_vert

more_vert