Trichuris trichiura (whipworm) is a soil-transmitted helminth (STH) endemic to areas with a tropical climate. Infection occurs after the soil-residing egg of T. trichiura is ingested.1 Eggs are expelled in the faeces of infected hosts and continue this cycle after a period of maturation in the soil.1 An estimated 600–800 million people are infected with T. trichiura worldwide and this infection is estimated to cause the loss of 1.6–6.4 million disability-adjusted life-years.1,2 T. trichiura is the most prevalent helminth in many countries surveyed.3–5 Heavy infections (> 10 000 eggs per gram of faeces) are associated with anaemia, malnutrition, the trichuris dysentery syndrome and rectal prolapse.6–8

The Northern Territory has a population of about 232 000 in a geographic area of 1 200 000 km2.9 Thirty per cent of the population is Indigenous and 80% of Indigenous residents live in remote locations.9 T. trichiura is one of three STHs that are endemic in the NT; the other two are Ancylostoma duodenale (hookworm) and Strongyloides stercoralis. A 1997 prevalence study found T. trichiura to be the commonest STH, with 25% of adults in a remote Indigenous community infected;10 no data on T. trichiura in the NT have been reported since. T. trichiura infection is difficult to treat and even more difficult to target within a deworming program. The Central Australian Rural Practitioners Association (CARPA) treatment manual currently recommends albendazole (400 mg) on 3 consecutive days for treatment of proven T. trichiura infection.11 This regimen has been correlated with a 50% cure rate.12 Since 2005, CARPA has recommended a single dose of albendazole (400 mg) for all children aged 6 months to 16 years as part of a community children’s deworming program. Empirical deworming is recommended before and after the wet season, or coinciding with child health assessments or school-age screening.11 Pregnant women are not targeted within this program. However, when pregnancy does occur within the target group, deworming with pyrantel is recommended.11

Under these deworming protocols, it has been reported that the prevalence of hookworm in the NT declined dramatically in the past 11 years and may be heading toward eradication.13 Our aim in this study was to describe the population at risk, disease associations and temporal trends of T. trichiura infections over the same 11 years.

In September 2013, we conducted a retrospective observational analysis of consecutive, microbiologically confirmed cases of T. trichiura infection in the NT between 1 January 2002 and 31 December 2012. Ethics approval for the study was obtained from the Human Research Ethics Committee of the NT Department of Health and Menzies School of Health Research (HREC-2013-1978).

Cases were identified from the NT Government pathology information system, Labtrak, which covers all NT Government health care facilities including five hospitals, two correctional centres and over 50 remote clinics. Previous STH studies13 have shown that the public NT laboratories identified 94% of all documented STHs, compared with 6% by other pathology service providers. Cases were diagnosed by examination of faeces specimens for T. trichiura eggs, other STHs and parasites by wet mount microscopy and a concentration method.14 Egg counts were not performed.

Infections were linked to NT Government electronic databases by means of medical record numbers to obtain data on age, sex, Indigenous status, place of residence, haemoglobin level and eosinophil count. Anaemia was defined as a haemoglobin level of ≤ 110 g/L and eosinophilia as an eosinophil count of ≥ 0.5 × 109/L.

Data were entered into a Microsoft Excel 2007 database (Microsoft Corporation) and analysed with Stata statistical software (version 13; Statacorp). Results are presented as medians and interquartile ranges (IQRs) for non-normally distributed parameters. The estimated prevalence rates in the NT for each year were expressed as cases per 100 000 Indigenous population per year with 95% confidence intervals. Indigenous population by age and percentage Indigenous population in the NT were obtained from Australian Bureau of Statistics data.15 Bivariate analyses were performed using the χ2 or Fisher exact test if expected frequencies were less than 5. For non-parametric data, the Mann–Whitney U test was used, with P values of < 0.05 considered significant.

There were 417 episodes of T. trichiura infection diagnosed in 400 patients from a total 63 668 faecal samples tested between 1 January 2002 and 31 December 2012. About 85% of these were from hospital inpatients admitted to Royal Darwin Hospital, usually for reasons other than T. trichiura infection. Thirteen patients were screened as part of a prisoner health check, 11 patients were living in the community and the remainder were inpatients of an NT Government health care facility (Royal Darwin Hospital, Alice Springs Hospital, Katherine District Hospital, Tennant Creek Hospital or Gove District Hospital) at the time of T. trichiura detection. The preponderance of inpatient samples comes about because community clinics are likely to send samples to private rather than government laboratories, and transport of samples from remote communities can be problematic.

Patients were considered to have had a repeat episode of infection if T. trichiura was detected at least 6 months after the first diagnosed episode (median duration between infections, 23.7 months; range, 7.8–100.9 months). Thirteen patients (3%) had two infections and two patients (0.5%) had three infections. Forty-three episodes of repeat T. trichiura infections that were detected in 33 patients within 6 months of the initially detected infection were deemed to be the same episode of infection and were excluded.

The demographic and laboratory parameters of patients with T. trichiura infection are shown in Box 1. Most infections were in children aged under 17 years (239; 59.8%), with 175 (43.8%) in children younger than 5 years. The median age of those infected was 8 years (IQR, 3–36 years). The vast majority of infections were in Indigenous patients (381 [95.3%] compared with 10 [2.5%] in non-Indigenous patients). Ethnicity was unknown for nine patients. Boys were more likely to be infected than girls (P < 0.001) and women were more likely to be infected than men (P < 0.001).

Haemoglobin levels and eosinophil counts were available for 356 and 345 of the 400 patients, respectively; 143 (40.2%) patients had anaemia and 178 (51.6%) had eosinophilia. After excluding episodes of T. trichiura infection where patients had co-infection with another STH, 115 patients (39.2%) had anaemia and 139 (34.8%) had eosinophilia. There were 112 children (46.9%) and 48 adults (29.8%) who had co-infection with at least one other faecal parasite (P = 0.001).

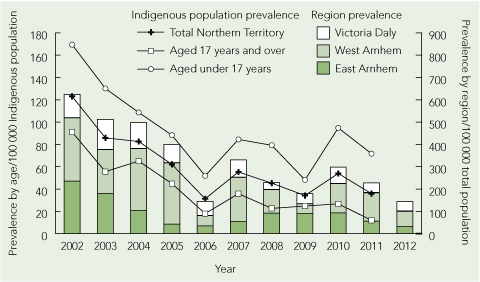

The period prevalence of T. trichiura infection (Box 2; and Appendix 1 (PDF)) decreased from 123.1 (95% CI, 94.8–151.3) cases per 100 000 Indigenous population in 2002 to 35.8 (95% CI, 21.8–49.9) cases per 100 000 Indigenous population in 2011. This downward trend was documented for both children and adults (Box 2). Most cases occurred in patients who had lived in one of three remote Top End NT locations, Victoria Daly, East Arnhem Land and West Arnhem Land (Appendix 2 (PDF)). The number of faecal microscopy samples tested each year was relatively constant, with a median of 5764 samples (range, 5276–6527 samples) per year. We were unable to obtain accurate data on numbers of doses of albendazole dispensed for the community children’s deworming program over our study period.

Our study shows that T. trichiura in the NT predominantly affects Indigenous patients from remote Top End communities. Children had the highest prevalence of infection across all the years in our study period. Among children, boys had a statistically significant higher proportion of infections. Conversely, women had a statistically significant higher proportion of infections. It is likely that adult women have higher rates of infection because they care for and live in closer proximity to infected children who contaminate the nearby environment. The difference we observed between the prevalence in boys and girls may reflect greater soil exposure among boys.

We found a strong association between T. trichiura infection, anaemia and eosinophilia, and this association persisted when coinfection with other STHs was excluded. The precise contribution that T. trichiura makes towards anaemia is difficult to ascertain, as infection occurs in populations with a high level of intestinal parasite co-infection, socioeconomic disadvantage and nutritional deficiencies.6

Our data show a consistent reduction in microbiologically diagnosed T. trichiura infections in the NT over the 11 years from 2002 to 2012. Despite this reduction, a significant percentage of infections (59.8%) continued to be diagnosed within the community children’s deworming program target population of children less than 17 years of age. This finding is most likely explained by the reduced efficacy of single-dose albendazole in T. trichiura infection compared with other STHs12,16 and to the rapid reinfection rates seen with T. trichiura.4 Similar disparities in reduction of infection with hookworm and T. trichiura in response to mass deworming campaigns have been observed elsewhere.17 Despite these poor cure rates, egg reduction rates of over 80%12 do occur with single-dose albendazole and this may be sufficient to protect our population against the morbidity seen in high-intensity infections. Interventions to improve sanitation are very effective in reducing the prevalence of T. trichiura infections,18 and level of maternal education, access to latrines, household wealth indexes and remoteness are important risk factors for infection.19

Our retrospective study has several limitations. Systematic sampling from the community was not undertaken, so the true prevalence rates are undoubtedly much higher than the laboratory-diagnosed rates found in our study population. Notably, all but 24 patients were inpatients of a NT Government health facility, reflecting a selection bias towards patients with acute illness and comorbid conditions. Furthermore, without a control group, the association of T. trichiura infection with anaemia cannot be further analysed. T. trichiura egg counts were not performed, so anaemia and eosinophilia correlates with the intensity of infection could not be determined.

We have shown a reducing T. trichiura infection rate in the NT over the 11 year period of our study. A large number of infections continue to be diagnosed in the community children’s deworming program target population. With the move towards eradication of hookworm in the NT, our data raise the question of whether the deworming program should be adapted to improve efficacy against T. trichiura (400 mg albendazole daily for 3 days). More importantly our study supports increasing the focus on health education, healthy living practices and essential housing infrastructure. These factors are deficient in remote Indigenous Australian communities20 and greatly impact on the prevalence of all STH infections.3,18,19

1 Demographic and laboratory parameters of 400 patients* with Trichuris trichiura infection,

Northern Territory, January 2002 to December 2012

|

|

Age group |

|

|||||||||||||

|

Parameter |

All |

< 17 years |

≥ 17 years |

P |

|||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||

|

400 (100%) |

239 (59.8%) |

161 (40.3%) |

< 0.001 |

||||||||||||

|

Sex |

|

|

|

< 0.001 |

|||||||||||

|

Male |

205 (51.3%) |

141 (59.0%) |

64 (39.8%) |

|

|||||||||||

|

Female |

195 (48.8%) |

98 (41.0%) |

97 (60.2%) |

|

|||||||||||

|

Indigenous status† |

|

|

|

< 0.001 |

|||||||||||

|

Indigenous |

381 (95.3%) |

236 (98.7%) |

145 (90.1%) |

|

|||||||||||

|

Non-Indigenous |

10 (2.5%) |

3 (1.3%) |

7 (4.3%) |

|

|||||||||||

|

Unknown |

9 (2.3%) |

0 (0) |

9 (5.6%) |

|

|||||||||||

|

Median haemoglobin level |

114 (104–125) |

114 (105–123) |

113 (95–130) |

|

|||||||||||

|

Anaemia‡ |

143 (40.2%) |

78 (32.6%) |

65 (40.4%) |

0.14 |

|||||||||||

|

Median eosinophil count |

0.5 (0.1–1.0) |

0.5 (0.1–1.2) |

0.5 (0.1–0.9) |

|

|||||||||||

|

Eosinophilia§ |

178 (51.6%) |

104 (43.5%) |

74 (46.0%) |

0.87 |

|||||||||||

|

Polyparasitism¶ |

160 (40.0%) |

112 (46.9%) |

48 (29.8%) |

0.001 |

|||||||||||

|

Episodes with no STH coinfection |

|

|

|

|

|||||||||||

|

Number |

333 (83.3%) |

205 (85.8%) |

128 (79.5%) |

0.10 |

|||||||||||

|

Median haemoglobin level |

114 (104–125) |

114 (105–124) |

114 (98–132) |

|

|||||||||||

|

Anaemia** |

115 (39.2%) |

66 (36.9%) |

49 (43.0%) |

0.30 |

|||||||||||

|

Median eosinophil count |

0.4 (0.1–0.9) |

0.4 (0.1–1.0) |

0.5 (0.1–0.8) |

|

|||||||||||

|

Eosinophilia†† |

139 (48.9%) |

82 (47.7%) |

57 (50.9%) |

0.60 |

|||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||

|

IQR = interquartile range. STH = soil-transmitted helminth. |

|||||||||||||||

more_vert

more_vert