Metastatic colorectal cancer (mCRC) is the fourth most common cause of cancer death in Australia.1 The past 15 years have seen improved outcomes in patients with mCRC, largely due to increased chemotherapeutic and biological treatment options and widespread adoption of liver resection for liver-limited mCRC.2 These improvements have led to an increase in reported median survival from 12 to 24 months since 1995. Despite these advances, patients with unresectable mCRC usually die from the disease, with 5-year overall survival of about 15%.2 Initial treatment for mCRC involves combination chemotherapy or single-agent therapy. Survival is improved in patients who ultimately receive all three active chemotherapy drugs (oxaliplatin, irinotecan and a fluoropyrimidine)3 and have access to biological agents, such as bevacizumab.2

Australia’s geographical challenges (large land area and low population density) contribute to difficulties in service provision and disparity of cancer outcomes.4 Some authors have suggested the observed higher death rate among Australia’s rural population is the result of a double disadvantage: higher exposure to health hazards and poorer access to health services.5,6 There is a complex interplay between remoteness of residence and other known causes of poor cancer outcome, including unequal exposure to environmental risk factors,5 less participation in cancer screening programs,7–9 delayed diagnosis,10 socioeconomic disadvantage,4,11 and higher proportions of disadvantaged groups such as Indigenous Australians.12 Despite these factors, an Australian study of patients with rectal cancer found that increasing distance between place of residence and a radiotherapy centre was independently associated with inferior survival.6 A recent analysis of cancer outcomes using population mortality data found that reductions in the cancer death rate between 2001 and 2010 were largely confined to the metropolitan population, with an estimated 8878 excess cancer deaths in regional and remote Australia, including 750 CRC deaths.13

Remoteness poses practical difficulties that may lead patients with cancer and their clinicians to make choices based on the need for travel, or because of perceived toxicity risks of different regimens. Population studies have shown that rural patients have reduced rates of radical surgery,9 less adjuvant radiotherapy,14 delays in commencing adjuvant chemotherapy15 and reduced clinical trial participation.16 Rural cancer patients can also face a significant financial and travel burden.17

Rural patients in South Australia have historically had limited access to regional oncology services, as population numbers outside metropolitan Adelaide are insufficient to support onsite oncologists. Until recently, this has meant that most chemotherapy is delivered in Adelaide, reflecting a more centralised service than in Australia’s eastern states. An effort is currently being made to shift to more rural chemotherapy delivery and an expanded visiting oncology service.18

In this study, we used the South Australian Clinical Registry for Metastatic Colorectal Cancer (SA mCRC registry) to investigate disparity in outcomes and treatment delivery for rural patients with mCRC compared with their metropolitan counterparts.

Methods

The SA mCRC registry is a state-wide population-based database of all patients diagnosed with synchronous or metachronous mCRC since February 2006. Previous registry-based analyses have led to the description of important associations of patient subgroups and outcomes.19–21 Core data include age, sex, demographics, tumour site, histological type, differentiation and metastatic sites. Treatment data consist of surgical procedures, chemotherapy (including targeted therapy), radiotherapy, radiofrequency ablation, and selective internal radiation therapy. The date and cause of death for each patient in the registry is obtained through medical records review and electronic linkage with state death records. Approval for this study was granted by the SA Health Human Research Ethics Committee.

For this study, we included data collected between 2 February 2006 and 28 May 2012. We compared the oncological and surgical management (primarily metastasectomy) and survival of metropolitan versus rural patients. Based on the accepted registry definitions, patients residing in metropolitan Adelaide (postcodes 5000–5174) were designated the “city” cohort, with all other patients (postcodes 5201–5799) in the “rural” cohort. Patient characteristics, use of chemotherapy across first, second and third lines of treatment, choice of first-line chemotherapy, hepatic resection rates and survival were analysed and compared between the city and rural patient cohorts.

All analyses were undertaken using Stata version 11 (StataCorp). Overall survival (OS) analysis was done using conventional Kaplan–Meier methods. Survival was calculated from the date of diagnosis of stage IV disease to the date of death, with a final censoring date of 28 May 2012. The log-rank test of equality was used for comparisons. OS was used as the end point because this outcome measure was available in the registry data and to avoid misclassification of cause of death in disease-specific survival.

Results

Patient characteristics

Data from 2289 patients, including 624 rural patients (27.3%), were available for analysis (Box 1). There was a higher proportion of male patients in the rural than the city cohort (62.7% v 53.6%; P < 0.001). The colon was the primary site of malignancy in a higher proportion of city than rural patients (75.7% v 71.5%; P = 0.04). Kirsten rat sarcoma viral oncogene homolog (KRAS) mutation testing was performed in around 14% of patients in both cohorts, and the proportion of KRAS exon 2 wild-type tumours was not significantly different between rural and city cohorts (59.8% v 59.7%; P = 0.96). Clinical trial participation did not differ significantly between the cohorts (7.1% v 9.2%; P = 0.10).

Treatment

Chemotherapy

First-line chemotherapy was administered in 58.3% of rural patients, compared with 56.0% of city patients (P = 0.32) (Box 2). As a percentage of patients who received any chemotherapy, rates of second-line (22.5% v 23.3%; P = 0.78) and third-line (9.3% v 10.1%; P = 0.69) chemotherapy administration were also similar between rural and city cohorts. There were differences between the cohorts in the type of first-line treatment: rural patients had less use of combination chemotherapy (59.9% v 67.4%; P = 0.01) and biological agents (16.8% v 23.7%; P = 0.007) than city patients, though numerically these differences were small. When an oxaliplatin combination was prescribed, the oral prodrug of 5-fluorouracil, capecitabine, was used more frequently in rural patients than city patients (22.9% v 8.4%; P < 0.001). Only 21 rural patients (5.8%), and no city patients, received their first dose of first-line chemotherapy in a rural chemotherapy centre.

Non-chemotherapy

Adoption of any of the non-chemotherapy treatment modalities did not differ significantly by place of residence (Box 3). Of note, there was no significant difference in rates of hepatic metastasectomy between city and rural cohorts (13.7% v 11.5%; P = 0.17). Pulmonary metastasectomy rates were higher in city patients (3.2% v 2.1%; P = 0.10), but total numbers were small.

Survival

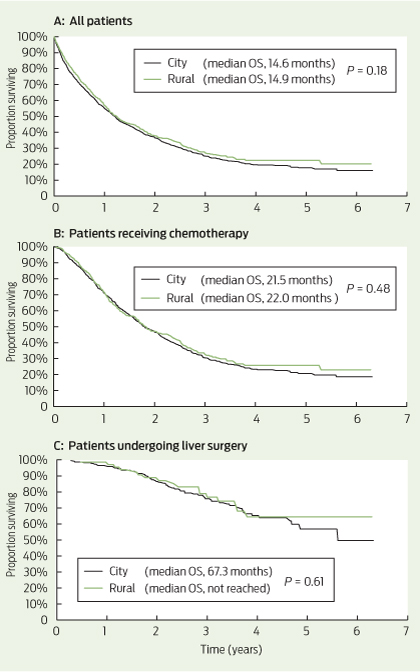

Among all patients, the median OS was 14.6 months for city patients and 14.9 months for rural patients (P = 0.18) (Box 4, A). Among patients receiving chemotherapy (with or without metastasectomy), the median OS was 21.5 months for city patients and 22.0 months for rural patients (P = 0.48) (Box 4, B). For patients undergoing liver metastasectomy, the median OS was 67.3 months for city patients and was not reached in rural patients (P = 0.61) (Box 4, C).

Discussion

Our results demonstrate that rural patients with mCRC in SA receive comparable treatment and have equivalent survival to their metropolitan counterparts. In particular, patients in rural areas are treated with equivalent rates of potentially curative metastasectomy and chemotherapy, two key determinants of length of survival. These are the first Australian data specifically analysing rates of chemotherapy in rural patients with mCRC, and they suggest the excess colon cancer mortality seen in rural patients relates to factors other than access to treatment in the metastatic setting.

While there were no significant differences between the cohorts in rates of patients receiving chemotherapy across all lines of treatment, rural patients received less first-line combination chemotherapy, increased use of capecitabine and reduced use of biological agents in the first line than city patients.

First-line combination chemotherapy with intravenous infusional 5-fluorouracil, folinic acid and oxaliplatin (FOLFOX) has equivalent efficacy to oral capecitabine and oxaliplatin (XELOX).22 The choice between the two regimens is based on differing toxicities and practical considerations. FOLFOX requires a central venous catheter (CVC) and a second visit to a chemotherapy day centre every fortnight for ambulatory pump disconnection. XELOX has the advantages of single 3-weekly clinic visits and no CVC, but compliance with twice-daily chemotherapy tablets and potentially higher rates of symptomatic toxicity (hand–foot syndrome and diarrhoea) are limitations. The higher use of XELOX among rural patients reflects the relative practical benefits of this regimen where travel distances and access to nursing staff trained in CVC management are important considerations. The potential for toxicity of XELOX requires careful patient education and system approaches to enable early recognition and intervention in the event of severe toxicity among rural, often isolated, patients. Early follow-up telephone calls by a nurse practitioner or telemedicine consultations are potential strategies to provide this important aspect of care to rural patients.23,24

We observed a small but significant reduction in the rate of biological agents used in first-line therapy for rural patients, mostly due to reduced bevacizumab prescribing. It is possible clinicians were reluctant to “intensify” therapy in rural patients due to a lack of supervision or access to health care, particularly given risks of haemorrhage. It is also possible this small difference reflects a chance finding. The pattern of bevacizumab prescribing has evolved over the period captured in the registry, and an updated analysis of patients diagnosed since 2010 may provide further insights.

The equivalent rate of attempted curative metastasectomy in rural mCRC patients compared with city patients is reassuring, given this approach provides the only option for long-term survival in mCRC. The survival curves of patients undergoing liver metastasectomy showed a survival plateau at 5 years of 50% or greater for both city and rural patients (Box 4, C). This compares favourably with other modern surgical case series, with reported 5-year survival of 32%–47% after liver resection.25

Delivery of specialised health care services for rural Australians requires policymakers to carefully balance the merits of a centralised versus a decentralised system, with unique consideration for each region. For example, no regional centres in SA have a population sufficient to support a full-time resident medical oncologist and are instead serviced by a visiting (fly-in fly-out) oncologist. Limited infrastructure and staff training have also largely prevented widespread administration of chemotherapy in regional centres. Highlighting this point, we found that only 5.8% of rural patients receiving chemotherapy received their first cycle in a rural treatment centre. The SA Statewide Cancer Control Plan 2011–2015 lists the establishment of regional cancer services and chemotherapy centres as a key future direction to optimise care for rural cancer patients.18 Unfortunately, no publications have assessed outcomes of rural patients with mCRC treated in other regions of Australia, particularly in the eastern states where regional oncology services are common. While our analysis supports equivalent survival outcomes for rural patients treated within SA’s largely centralised service, the practical, social and economic advantages of regional cancer centres remain an important consideration not captured in our study. Given this, we consider that our findings highlight the positive outcomes achieved through high-quality, specialised care, rather than suggest that current regional services in Australia should also adopt a centralised approach.

As our analysis dichotomised patients into city and rural cohorts, it does not provide outcome information based on the degree of remoteness. Despite this limitation, chemotherapy and surgical treatment were almost entirely delivered in Adelaide, and thus our analysis appropriately distinguishes those patients who had to travel to access oncological care. The possibility of inadequate registry ascertainment of rural cases of mCRC also poses a possible limitation. However, we are confident this is not a source of bias, as the registry collects information from all histopathology reports in SA, which are processed centrally in Adelaide. An important limitation of our study is that we report only on mCRC, and stage I–III disease is not included. The impact of treatment differences in early-stage CRC (eg, quality and timeliness of surgery, use of adjuvant chemotherapy) on overall survival of patients with mCRC cannot be determined in this analysis. Reassuringly, however, about two-thirds of mCRC cases in both cohorts were synchronous (ie, no prior early-stage disease), suggesting this is unlikely to limit our conclusions. Further, the equivalent rates of synchronous diagnosis in rural and urban patients may suggest there was no major delay in diagnosis of rural patients.

Although higher cancer incidence and poorer outcomes have been consistently demonstrated for rural cancer patients in Australia, we found equivalent treatment patterns and survival for rural patients diagnosed with mCRC in SA since 2006 compared with their metropolitan counterparts. This confirms optimal treatment of rural patients results in equivalent outcomes to metropolitan patients, irrespective of disadvantage. Further, it suggests previously demonstrated disparate outcomes may be due to factors such as higher incidence of CRC as a result of burden of risk factors and potentially reduced screening participation, rather than treatment factors once mCRC has been diagnosed. Targeting these factors is likely to provide the greatest impact on reducing the excess cancer burden for rural Australians.

1 Patient characteristics, by city versus rural residence (n = 2289)*

|

Characteristic

|

City

|

Rural

|

P†

|

|

|

No. (%) of patients

|

1665 (72.7%)

|

624 (27.3%)

|

|

|

Median age (range), years

|

73 (17–105)

|

72 (31–100)

|

0.11

|

|

Sex

|

|

|

|

|

Male

|

893 (53.6%)

|

391 (62.7%)

|

< 0.001

|

|

Female

|

772 (46.4%)

|

233 (37.3%)

|

|

|

Primary site

|

|

|

|

|

Colon

|

1260 (75.7%)

|

446 (71.5%)

|

0.04

|

|

Rectum

|

405 (24.3%)

|

178 (28.5%)

|

|

|

Synchronous disease

|

1070 (64.3%)

|

407 (65.2%)

|

0.67

|

|

Site of metastasis

|

|

|

|

|

Liver only

|

665 (39.9%)

|

226 (36.2%)

|

0.10

|

|

Lung only

|

128 (7.7%)

|

45 (7.2%)

|

0.70

|

|

Liver and lung only

|

178 (10.7%)

|

65 (10.4%)

|

0.85

|

|

All other sites

|

694 (41.7%)

|

290 (46.5%)

|

0.13

|

|

> 3 metastatic sites

|

138 (8.2%)

|

54 (8.7%)

|

0.38

|

|

KRAS testing

|

243 (14.6%)

|

87 (13.9%)

|

0.77

|

|

KRAS wild-type

|

145 (59.7%)

|

52 (59.8%)

|

0.96

|

|

Clinical trial participation

|

154 (9.2%)

|

44 (7.1%)

|

0.10

|

|

|

KRAS = Kirsten rat sarcoma viral oncogene homolog. * Data are number (%) of patients unless otherwise indicated. † P values calculated using χ2 tests.

|

2 Frequency of first-line, second-line and third-line chemotherapy, and regimens, by city versus rural residence

| |

First-line treatment

|

Second-line treatment

|

Third-line treatment

|

|

Regimen

|

City

|

Rural

|

P

|

City

|

Rural

|

P

|

City

|

Rural

|

P

|

|

|

Total

|

933 (56.0%)

|

364 (58.3%)

|

0.32

|

217 (23.3%)*

|

82 (22.5%)*

|

0.78

|

94 (10.1%)*

|

34 (9.3%)*

|

0.69

|

|

Single-agent chemotherapy

|

271 (29.0%)

|

118 (32.4%)

|

0.23

|

58 (26.7%)

|

18 (22.0%)

|

0.40

|

21 (22.3%)

|

7 (20.6%)

|

0.83

|

|

Capecitabine

|

202

|

82

|

0.30

|

24

|

4

|

|

8

|

0

|

|

|

5-FU

|

58

|

31

|

0.29

|

3

|

3

|

|

4

|

1

|

|

|

Irinotecan

|

11

|

3

|

|

31

|

11

|

|

9

|

6

|

|

|

Oxaliplatin

|

0

|

2

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Combination chemotherapy

|

629 (67.4%)

|

218 (59.9%)

|

0.01

|

115 (53.0%)

|

44 (53.7%)

|

0.92

|

49 (52.1%)

|

17 (50.0%)

|

0.83

|

|

FOLFOX

|

491

|

146

|

0.001

|

21

|

8

|

|

14

|

2

|

|

|

XELOX

|

53

|

50

|

< 0.001

|

15

|

4

|

|

8

|

2

|

|

|

FOLFIRI

|

76

|

18

|

0.12

|

62

|

26

|

|

15

|

7

|

|

|

XELIRI

|

1

|

0

|

|

1

|

2

|

|

2

|

2

|

|

|

MMC–5-FU or capecitabine

|

8

|

4

|

|

16

|

4

|

|

10

|

4

|

|

|

Other†

|

33 (3.5%)

|

28 (7.7%)

|

|

44 (20.3%)

|

20 (24.4%)

|

|

24 (25.5%)

|

10 (29.4%)

|

|

|

Biological agent

|

221 (23.7%)

|

61 (16.8%)

|

0.007

|

97 (44.7%)

|

30 (36.6%)

|

0.21

|

72 (76.6%)

|

34 (100%)

|

0.003

|

|

Bevacizumab

|

185

|

52

|

|

60

|

22

|

|

16

|

14

|

|

|

EGFR mAb

|

15

|

5

|

|

26

|

8

|

|

52

|

19

|

|

|

Other

|

21

|

4

|

|

11

|

1

|

|

4

|

1

|

|

|

|

5-FU = 5-fluorouracil. FOLFOX = folinic acid–5-FU–oxaliplatin. XELOX = capecitabine–oxaliplatin. FOLFIRI = folinic acid–5-FU–irinotecan. XELIRI = capecitabine–irinotecan. MMC = mitomycin C. EGFR mAB = epidermal growth factor receptor monoclonal antibody. * Total rates of second-line and third-line chemotherapy use are expressed as a percentage of patients who received any chemotherapy. † Includes use of raltitrexed and MMC (as single agent and combination).

|

3 Frequency of non-chemotherapy treatments, by city versus rural residence

|

Treatment

|

City (n = 1665)

|

Rural (n = 624)

|

P

|

|

|

Lung resection

|

53 (3.2%)

|

13 (2.1%)

|

0.10

|

|

Hepatic resection

|

228 (13.7%)

|

72 (11.5%)

|

0.17

|

|

Surgery*

|

858 (51.5%)

|

345 (55.3%)

|

0.11

|

|

Ablation

|

12 (0.7%)

|

3 (0.5%)

|

0.53

|

|

Selective internal radiation therapy

|

10 (0.6%)

|

8 (1.3%)

|

0.10

|

|

Radiotherapy

|

299 (18.0%)

|

132 (21.2%)

|

0.08

|

|

|

* Includes resection of colorectal primary cancer.

|

4 Overall survival (OS) in city versus rural patients

more_vert

more_vert