In-hospital falls remain a major cause of harm in acute care hospitals; a multicentre study estimated that falls comprised about 40% of all reported patient incidents (11 766 of 28 998) in the British National Health System.1 They result in additional hospital costs because of their impact on hospital length of stay (LOS) and use of resources.2 Previous studies of the costs of falls have had methodological limitations — small samples from single hospitals, capture of fall events using single sources (resulting in measurement bias),3–5 modelled costs based on diagnosis-related group or per diem costs (known to be crude estimates of cost), or costing data more than 10 years old. Poor capture of fall events will result in inaccurate estimates of cost,6 while modelled costs are unlikely to reflect the true total cost attributable to the fall. Further, most studies have focused on falls resulting in serious injury,7,8 underestimating the total financial burden of in-hospital falls.

In Australia, only one study has examined the differences in the demand on resources by fallers and non-fallers in the acute hospital setting.9 This retrospective study was undertaken in a sample of 151 patients from a single hospital. Fallers were grouped by diagnosis-related group, and it was found that the LOS of patients who experienced a fall in hospital was up to 11 days longer than that of non-fallers (matched for age and sex). Costing analysis was undertaken for patients with complete costing data in the three most common diagnosis-related groups (39 pairs). Total hospital-related costs for fallers were reported to be double those for non-fallers, although no figures were cited. While this study provided insights into the increased consumption of resources caused by falls, the small sample consisted of a select group of patients from only one hospital. For this reason, data that can be generalised to the broader acute population in Australia are still needed.

Given the lack of comprehensive and contemporary data on the cost of falls, the aim of our study was to identify the economic burden associated with in-hospital falls in six Australian hospitals. The study had three main objectives:

-

to calculate the difference between the hospital LOS and costs of patients who experienced at least one in-hospital fall and of those who had not;

-

to calculate the difference between the hospital LOS and costs of patients who experienced at least one in-hospital fall injury and of those who had a non-injurious fall; and

-

to estimate the incremental change in hospital LOS and costs associated with each in-hospital fall or fall injury.

Methods

Study design

This multisite prospective study of the cost of falls was conducted as part of a larger falls prevention cluster randomised control trial, the 6-PACK project.10 A detailed description of the methods used in this study has been published elsewhere.6

Study population and setting

Our study included all patient admissions to 12 acute hospital wards in six public hospitals (metropolitan and regional teaching hospitals) in two Australian states (Victoria and New South Wales). The sample was restricted to wards randomised to the control group of the 6-PACK trial to minimise confounding due to the effects of the 6-PACK program. Participating wards included four general medical, two general surgical, one general medical short-stay, four specialist medical and one specialist surgical wards. All wards continued their standard care falls prevention practices during the study period.

Data collection and data sources

Data were prospectively collected in each hospital over a 15-month period during 2011–2013, including 3-month baseline and 12-month cluster randomised controlled trial study periods.

Fall events

An in-hospital fall was defined as “an event resulting in a person coming to rest inadvertently on the ground, floor, or other lower level”11 during their hospital stay. A fall injury was defined as any reported physical harm resulting from a fall; the injuries were classified as no injury, mild, moderate or major according to the definitions provided by Morse12 (Box 1).

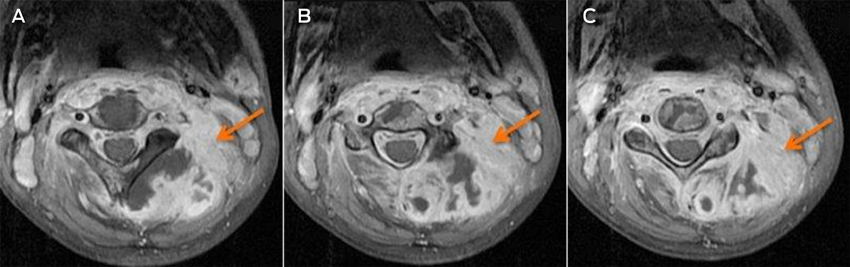

Falls data were prospectively collected using a multimodal method to ensure maximal capture of falls events: (1) daily patient medical record audit; (2) daily verbal reports from the ward nurse unit manager; and (3) data extracts obtained from hospital incident reporting and administrative databases. Radiological investigation reports were reviewed to verify fractures. All recorded falls were reviewed and re-coded by a second independent assessor, and disagreements resolved by a third.

Patient hospital utilisation

Patient hospital utilisation was assessed on the basis of inpatient LOS and hospital episode costs. LOS was defined as the total number of hospital bed-days (calculated from the day of hospital admission to the day of discharge) and was extracted for all study participants from hospital administrative datasets. Patient hospital episode costs were extracted from hospital clinical costing systems. Hospitals with incomplete or poor-quality costing data (three of the six participating hospitals) were omitted from the costing analysis, but not from the LOS analysis; this involved 13 489 admissions, or 49.9% of the total number of admissions. Costs are reported in Australian dollars and were inflated to the base year 2013, based on the Australian Bureau of Statistics consumer price index for hospital services.13

Other hospital admission covariates

Data on patient demographics (age, sex) and admission characteristics (admission source, admission type, diagnoses) were obtained from hospital administrative datasets for all participants. Age was coded into four categories (< 55 years, 55–69 years, 70–84 years, ≥ 85 years). Admission type was coded into four categories (emergency v elective, and medical v surgical, based on diagnosis-related group classification). To account for comorbid illness on admission, comorbidities were generated with the Elixhauser comorbidity method.14 The assessment of cognitive impairment on or during a patient’s admission was based on International Classification of Diseases, 10th revision, Australian modification (ICD-10-AM) codes for dementia or delirium. A history of falls was defined as presenting with a fall or a history of falls coded as either the principal reason for admission or as an associated condition on admission.

Data linkage

Hospital administrative datasets were linked to data on fall events (linking variables: patient identifier, date of admission, date of event, ward). Data were then linked to patient hospital costing data (linking variables: patient identifier, date of admission). Three patients (0.02% of cohort) with missing costing data were excluded from the analysis of costs.

Statistical analysis

Descriptive and bivariate analyses of patient and admission characteristics and of hospital utilisation for each hospital admission were undertaken. Hospital LOS and costs were reported as means (with standard deviations) and medians (with interquartile ranges). If a patient was admitted to hospital several times during the study period, each admission was treated as a separate event. For patient admissions with an identified fall or fall injury, we analysed the average additional hospital LOS and costs with multivariate linear regression models (Box 2).

All analyses were adjusted for prespecified variables (age, sex, cognitive impairment6) and clustering by hospital (to account for in-hospital correlations). Additional admission covariates were included in the regression analysis if P < 0.25 in the bivariate analysis, or if they were clinically significant according to clinical opinion and literature. Standard errors were calculated using a bootstrap approach.15 Statistical significance was defined as P < 0.05 for all analyses. Data were analysed with Stata version 13 (StataCorp).

As hospital LOS and costing data were each positively skewed, cross-validation of the linear regression analyses was undertaken with generalised linear models that estimated the adjusted relative increase in LOS and costs for falls and fall injuries, using Poisson and gamma error distributions, respectively, and including a log-link function. In addition, multivariate linear regression analyses were undertaken, with log transformation of LOS and cost data. The smearing estimator developed by Duan and colleagues16 was used to retransform covariates from the log-scale back to the original scale (Australian dollars).

Sensitivity analysis

Sensitivity analyses were undertaken that separately compared the data of non-injured fallers with those of non-fallers, and of injured fallers with those of non-fallers. To examine the robustness of the cost of fall estimates, sensitivity analyses were undertaken that individually removed each of the hospitals to determine their influence on hospital costs and LOS, or that excluded patients who were deemed by visual inspection to be extreme statistical outliers (costs or LOS).

Ethics approval

This study received multicentre ethics approval from the Monash University Human Research Ethics Committee (project number CF11/0229–2011000072). Ethics and research governance approval was also obtained from local ethics committees at all participating hospitals.

Results

Our study included 21 673 unique patients and 27 026 patient hospital admissions (Box 3). We found that 966 hospital admissions (3.6%) involved at least one fall, and 313 (1.2%) at least one fall injury, a total of 1330 falls and 418 fall injuries. A summary of the numbers and types of fall events are summarised by hospital in Appendix 1.

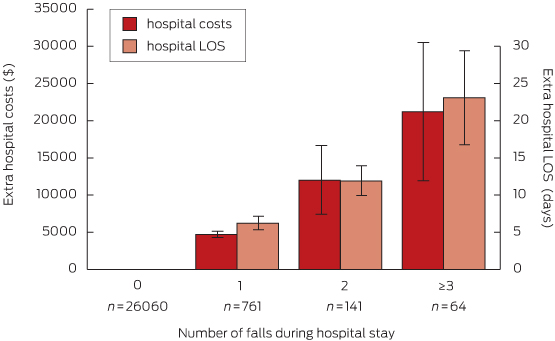

Data for hospital LOS and costs for the total cohort and by group are summarised in Box 4. The total hospital costs of fallers in this dataset were $9.8 million, with $6.4 million attributable to non-injured fallers and $3.4 million to injured fallers. After adjustment for age, sex, cognitive impairment, admission type, comorbidity, history of falls on admission and clustering by hospital, the mean LOS for fallers was 8 days longer (95% CI, 5.8–10.4; P < 0.001) than for non-fallers, and on average they incurred $6669 more in hospital costs (95% CI, $3888–$9450; P < 0.001) (model 1a, Box 5). Each additional fall was associated with a longer LOS and additional hospital costs; the LOS for patients who experienced three or more falls was estimated as being 23 days longer (95% CI, 10.7–35.4; P = 0.003) than for non-fallers, and they incurred more than $21 000 in additional hospital costs (95% CI, $3035–$39 355; P < 0.001) (model 1b, Box 6).

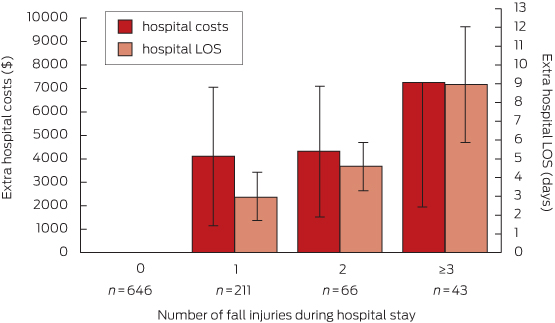

Within the cohort of fallers, the mean LOS for an injured faller was 4 days longer (95% CI, 1.8–6.6; P = 0.001) than for a faller without injury. Consistent with our other findings, mean hospital costs were also higher (by $4727; 95% CI, −$568 to $10 022; P = 0.08), but the difference was not statistically significant (model 2a, Box 5). Each additional fall injury was associated with increased LOS and additional hospital costs (model 2b, Box 7); patients who experienced three or more in-hospital fall injuries were estimated to have a mean increase in LOS of 9 days (95% CI, 2.8–15.1; P = 0.004) compared with a faller without injury, and incurred more than $7000 in extra hospital costs (95% CI, −$3126 to $17 636; P = 0.171) (Box 7). There were no statistically significant differences in hospital LOS or costs associated with the severity of a fall-related injury (189 hospital admissions with mild injury, 89 with moderate injury, 35 with severe injury; model 2c). Results from models 1b, 2b and 2c are summarised in Appendix 2.

The cross-validation analyses of the linear regression using generalised linear models and log transformation of LOS and costs (Appendix 3) did not alter our conclusions.

Sensitivity analyses

Fallers who did not sustain injuries were estimated to have a mean increase in LOS of 7 days (95% CI, 5.1–8.7; P < 0.001) compared with non-fallers, and incurred mean additional hospital costs of $5395 (95% CI, $3788–$7002, P < 0.001). Injured fallers were estimated to have a mean increase of LOS of 11 days (95% CI, 5.1–8.7; P < 0.001) compared with non-fallers, and incurred mean additional hospital costs of $9917 (95% CI, $3273–$16 561; P = 0.003). Additional sensitivity analyses were undertaken to examine the robustness of study estimates by individually excluding each hospital from the analysis, and by excluding 78 patient admissions that appeared to be outliers with respect to hospital LOS or costs. There were no appreciable differences in the excess LOS or costs calculated by these analyses (results available from authors on request).

Discussion

This study found that in-hospital falls remain highly prevalent, with 3.6% of all patient admissions resulting in at least one fall, a third of which caused a fall injury. They are a significant burden on hospital resources because of the resulting increases in hospital LOS and costs, with patients who experience an in-hospital fall having nearly twice the LOS and costs of non-fallers. Our study shows that more than half of the additional costs associated with a fall injury can be attributed to the fall itself, not the injury.

The increase in resource burden associated with an in-hospital fall, whether the patient sustains an injury or not, may be caused by changes in the patient’s care pathway and discharge planning. Previous studies have found that a fall (regardless of injury) will affect the patient’s confidence and independence,17 and therefore influences their rate of recovery and plan to leave hospital. Best practice guidelines recommend that patients who have a fall be provided with strategies that minimise the risk of subsequent falls and an assessment of safety and readiness for discharge home.18,19 As a result, delivery of guideline-based care is likely to influence the overall hospital LOS, regardless of injury, and thus their use of hospital resources.

However, as our study was observational, it is possible that a fall might be the consequence of a patient’s longer hospital stay rather than its cause. Patients at risk of falling in the acute hospital setting are typically acutely unwell, often have multiple comorbidities, and take several medications. A fall may therefore reflect deterioration in an individual’s health and function rather than cause it. Further exploration of temporal trends in the occurrence of falls and the care pathway of patients following a fall event are warranted.

Some limitations should be considered when interpreting our findings. While we adjusted our analyses for potential confounding factors, unmeasured characteristics may have influenced hospital cost and LOS outcomes. These include differences in patient management across wards, severity of illness and acuity of care. There are also limitations associated with analysis of routinely collected hospital data for the assessment of health conditions,20 which may have resulted in the undercoding of confounding factors. However, the coding quality of ICD-10-AM in Australia has been found to be good to excellent for many diagnostic codes and comorbidities.21

The use of hospital costing data also poses challenges. While analysis of clinical costing data is a powerful research tool and aims to preserve information about variability in individual patient resource use,22 clinical costing standards are relatively new for Australian public hospitals. We observed some variability in the completeness and quality of the available costing data, and hospitals with incomplete or poor-quality costing data were removed from our costing analysis, resulting in a sample that included about half of the total study cohort. Finally, the results from our study only incorporated costs of hospitalisation from the acute hospital perspective, potentially providing a more conservative estimate of the overall resource burden.

Fall rates in the acute hospital setting remain unacceptably high and are clearly associated with longer hospital patient stays and higher hospital costs. The resource burden of in-hospital falls for the Australian hospital system is considerable. Our findings highlight the fact that falls prevention programs in the acute hospital setting need to focus not only on the minimisation of harm resulting from falls, but also on the prevention of all falls. In the absence of evidence from randomised control trials that supports the effectiveness of any single falls prevention strategy in the acute hospital setting,23 the challenge remains to develop innovative ways to prevent falls in hospital and to reduce the additional resource burden associated with these events. Our findings have important financial implications for hospitals in light of an ageing population and the growth in the burden of disease, and the complexity of patients within a health care system facing major cost constraints.

Box 1 –

Fall injury classification, according to Morse12

-

No injury: No physical damage (observed or documented) as a result of the fall

-

Mild injury: An injury (such as a bruise, swelling, abrasion, laceration or skin tear) that does not require medical treatment other than simple analgesia, such as paracetamol

-

Moderate fall injury: Dislocation, sprain and/or an injury that requires medical or surgical treatment

-

Major fall injury: Any fracture or head injury (open or closed), including subdural haematoma

Box 2 –

Linear regression models for analysis of additional hospital length of stay (LOS) and costs associated with a fall or fall-related injury

|

Model

|

Definition

|

|

|

1a

|

Additional hospital costs and LOS of patients who experience at least one in-hospital fall (fallers), compared with those who do not (non-fallers)

|

|

1b

|

Additional hospital costs and LOS of each additional in-hospital fall (1, 2, ≥ 3 falls) compared with non-fallers

|

|

2a

|

Additional hospital costs and LOS of patients who experience at least one in-hospital fall injury (injured fallers), compared with those who fell at least once but were not injured (non-injured fallers)

|

|

2b

|

Additional hospital costs and LOS of each additional in-hospital fall injury (1, 2, ≥ 3 injuries) compared with non-injured fallers

|

|

2c

|

Incremental hospital costs and LOS associated with the type of fall injury (based on the injury classification: mild, moderate and major fall injuries) compared with non-injured fallers

|

|

|

|

Box 3 –

Characteristics of the study cohort

|

Characteristic

|

All hospital admissions (n = 27 026)

|

Hospital admissions by faller status

|

Hospital admissions by injury status

|

|

Faller (n = 966)

|

Non-faller (n = 26 060)

|

P

|

Injured faller (n = 313)

|

Non-injured faller (n = 653)

|

P

|

|

|

Age

|

|

|

|

< 0.001

|

|

|

0.064

|

|

< 55 years

|

8332 (30.8%)

|

120 (12.4%)

|

8212 (31.5%)

|

|

32 (10.2%)

|

88 (13.5%)

|

|

|

55–69 years

|

6626 (24.5%)

|

188 (19.4%)

|

6438 (24.7%)

|

|

51 (16.3%)

|

137 (21.0%)

|

|

|

70–84 years

|

8730 (32.3%)

|

451 (46.7%)

|

8279 (31.8%)

|

|

152 (48.6%)

|

299 (45.8%)

|

|

|

≥ 85 years

|

3338 (12.4%)

|

207 (21.4%)

|

3131 (12.0%)

|

|

78 (24.9%)

|

129 (19.8%)

|

|

|

Sex (female)

|

12 997 (48.1%)

|

400 (41.4%)

|

12 597 (48.3%)

|

< 0.001

|

112 (35.8%)

|

288 (44.1%)

|

0.055

|

|

Admission type

|

|

|

|

< 0.001

|

|

|

0.338

|

|

Medical non-emergency

|

2421 (9.0%)

|

105 (10.9%)

|

2316 (8.9%)

|

|

34 (10.9%)

|

71 (10.9%)

|

|

|

Medical emergency

|

16 232 (60.1%)

|

637 (65.9%)

|

15 595 (59.8%)

|

|

207 (66.1%)

|

430 (65.8%)

|

|

|

Surgical non-emergency

|

4585 (17.0%)

|

122 (12.6%)

|

4501 (17.3%)

|

|

19 (6.1%)

|

65 (10.0%)

|

|

|

Surgical emergency

|

3355 (12.4%)

|

84 (8.7%)

|

3233 (12.4%)

|

|

45 (14.4%)

|

77 (11.8%)

|

|

|

Not recorded

|

433 (1.6%)

|

18 (1.9%)

|

415 (1.6%)

|

|

8 (2.6%)

|

10 (1.5%)

|

|

|

Admitted from nursing home

|

166 (0.6%)

|

13 (1.3)

|

153 (0.6%)

|

0.001

|

3 (1.0%)

|

10 (1.5%)

|

0.267

|

|

Reason for hospital admission

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Injuries

|

3852 (14.3%)

|

114 (11.8%)

|

3738 (14.3%)

|

< 0.001

|

37 (11.8%)

|

77 (11.8%)

|

0.602

|

|

Digestive system diseases

|

3512 (13.0%)

|

71 (7.3%)

|

3441 (13.2%)

|

0.042

|

31 (9.9%)

|

40 (6.1%)

|

0.130

|

|

Circulatory system diseases

|

3150 (11.7%)

|

115 (11.9%)

|

3035 (11.6%)

|

0.907

|

25 (8.0%)

|

90 (13.8%)

|

0.008

|

|

Respiratory system diseases

|

3051 (11.3%)

|

107 (11.1%)

|

2944 (11.3%)

|

0.706

|

36 (11.5%)

|

71 (10.9%)

|

0.896

|

|

Cancer

|

3029 (11.2%)

|

152 (15.7%)

|

2877 (11.0%)

|

< 0.001

|

49 (15.7%)

|

103 (15.8%)

|

0.533

|

|

Genitourinary system diseases

|

1867 (6.9%)

|

48 (5.0%)

|

1819 (7.0%)

|

0.535

|

19 (6.1%)

|

29 (4.4%)

|

0.062

|

|

Musculoskeletal and connective tissues disease

|

1309 (4.8%)

|

41 (4.2%)

|

1268 (4.9%)

|

0.027

|

11 (3.5%)

|

30 (4.6%)

|

0.338

|

|

Endocrine, nutritional, metabolic diseases

|

989 (3.7%)

|

57 (5.9%)

|

932 (3.6%)

|

0.010

|

20 (6.4%)

|

37 (5.7%)

|

0.440

|

|

Infectious and parasitic diseases

|

978 (3.6%)

|

40 (4.1%)

|

938 (3.6%)

|

0.755

|

15 (4.8%)

|

25 (3.8%)

|

0.775

|

|

Mental and behavioural disorders

|

536 (2.0%)

|

59 (6.1%)

|

477 (1.8%)

|

< 0.001

|

17 (5.4%)

|

42 (6.4%)

|

0.587

|

|

Other

|

4753 (17.6%)

|

162 (16.8%)

|

4591 (17.6%)

|

0.584

|

53 (16.9%)

|

109 (16.7%)

|

0.782

|

|

Presence of cognitive impairment during admission*

|

1882 (7.0%)

|

270 (28.0%)

|

1612 (6.2%)

|

< 0.001

|

93 (29.7%)

|

177 (27.1%)

|

0.061

|

|

Total number of comorbidities on admission, mean (SD)†

|

1.8 (2.7)

|

2.5 (1.5)

|

1.5 (1.8)

|

< 0.001

|

2.7 (1.8)

|

2.4 (1.8)

|

0.532

|

|

History of falls on admission‡

|

2042 (7.6%)

|

133 (13.8%)

|

1961 (7.5%)

|

0.001

|

53 (16.9%)

|

80 (12.3%)

|

0.008

|

|

|

∗ICD-10-AM codes for delirium and dementia: F050, F051, F058, F059, F104, F106, F114, F124, F134, F144, F154, F164, F174, F184, F194, F430, F00-F03, G30, G311, G309. †Elixhauser comorbidity method.14 ‡ICD-10-AM codes for history of falls: W00, W01-10, W13-15 W17-19.

|

Box 4 –

Hospital length of stay and hospital costs for patient hospital admissions

|

Hospital length of stay

|

All hospital admissions (n = 27 026)

|

Hospital admissions with a fall (n = 966)

|

|

Hospital admissions without a fall (n = 26 060)

|

Hospital admissions with a fall (n = 966)

|

Admissions without a fall injury (n = 653)

|

Admissions with a fall injury (n = 313)

|

|

|

Mean hospital length of stay, days (SD)

|

7.9 (8.5)

|

19.5 (17.6)

|

18.0 (15.0)

|

22.5 (21.9)

|

|

Median hospital length of stay, days (IQR)

|

5 (3–9)

|

14 (9–24)

|

14 (8–23)

|

17 (9–27)

|

|

Hospital costs

|

All hospital admissions (n = 13 489)

|

Hospital admissions with a fall (n = 533)

|

|

Hospital admissions without a fall (n = 12 956)

|

Hospital admissions with a fall (n = 533)

|

Admissions without a fall injury (n = 376)

|

Admissions with a fall injury (n = 157)

|

|

|

Mean hospital costs, $ (SD)

|

9368 (12 572)

|

19 289 (21 712)

|

17 897 (17 317)

|

22 623 (29 511)

|

|

Median hospital costs, $ (IQR)

|

6038 (3658–10 585)

|

12 833 (8314–21 261)

|

12 821 (8440–20 904)

|

13 563 (7850–21 500)

|

|

|

IQR = interquartile range.

|

Box 5 –

Adjusted increased hospital use by patients with an in-hospital fall or fall injury (multivariate linear regression models)∗

|

|

Mean hospital length of stay, days (95% CI)

|

P

|

Mean hospital costs, $ (95% CI)

|

P

|

|

|

Faller (model 1a)

|

8.1 (5.8 to 10.4)

|

< 0.001

|

6669 (3888 to 9450)

|

< 0.001

|

|

Sex (female)

|

0.4 (0.2 to 0.6)

|

|

566 (41 to 1092)

|

0.035

|

|

Age

|

|

|

|

|

|

< 55 years

|

1.0

|

< 0.001

|

1.0

|

|

|

55–69 years

|

1.1 (0.6 to 1.6)

|

< 0.001

|

839 (−1575 to 3253)

|

0.496

|

|

70–84 years

|

1.6 (0.7 to 2.4)

|

< 0.001

|

1,698 (−856 to 4251)

|

0.193

|

|

≥ 85 years

|

2.0 (0.9 to 3.0)

|

< 0.001

|

795 (−1353 to 2944)

|

0.468

|

|

Cognitive impairment

|

4.8 (3.4 to 6.2)

|

< 0.001

|

5229 (943 to 9515)

|

0.017

|

|

Admission type

|

|

|

|

|

|

Medical non-emergency

|

1.0

|

|

1.0

|

|

|

Medical emergency

|

0.9 (−0.3 to 2.2)

|

0.146

|

906 (−524 to 2337)

|

0.214

|

|

Surgical non-emergency

|

1.7 (0.2 to 3.2)

|

0.023

|

7,330 (3730 to 10 930)

|

< 0.001

|

|

Surgical emergency

|

6.1 (3.9 to 8.2)

|

< 0.001

|

12 407 (1487 to 23 327)

|

0.026

|

|

Number of comorbidities†

|

2.1 (1.5 to 2.6)

|

< 0.001

|

2605 (1564 to 3647)

|

< 0.001

|

|

Admitted from nursing home

|

−0.3 (−2.7 to 2.2)

|

0.831

|

4549 (−2697 to 11 794)

|

0.219

|

|

History of falls on admission

|

0.5 (−1.1 to 2.0)

|

0.567

|

−549 (−2490 to 1393)

|

0.580

|

|

Injured faller (model 2a)

|

4.2 (1.8 to 6.6)

|

0.001

|

4727 (−568 to 10 022)

|

0.080

|

|

Sex (female)

|

1.0 (−0.8 to 2.8)

|

0.278

|

519 (−1580 to 2618)

|

0.628

|

|

Age

|

|

|

|

|

|

< 55 years

|

1.0

|

0.784

|

1.0

|

|

|

55–69 years

|

−0.4 (−3.0 to 2.2)

|

0.556

|

−7095 (−20 182 to 5992)

|

0.288

|

|

70–84 years

|

−0.9 (−3.9 to 2.1)

|

0.111

|

−5772 (−17 208 to 5665)

|

0.323

|

|

≥ 85 years

|

−1.3 (−2.9 to 0.3)

|

<0.001

|

−8436 (−20 759 to 3887)

|

0.180

|

|

Cognitive impairment

|

5.3 (2.6 to 8.0)

|

|

6865 (1575 to 12 155)

|

0.011

|

|

Admission type

|

|

|

|

|

|

Medical non-emergency

|

1.0

|

|

1.0

|

|

|

Medical emergency

|

−0.7 (−3.7 to 2.4)

|

0.664

|

−973 (−3103 to 1157)

|

0.371

|

|

Surgical non-emergency

|

9.7 (2.9 to 16.5)

|

0.005

|

11 272 (2769 to 19 774)

|

0.009

|

|

Surgical emergency

|

10.3 (5.2 to 15.2)

|

< 0.001

|

19 706 (1530 to 37 881)

|

0.034

|

|

Number of comorbidities†

|

2.7 (1.3 to 4.2)

|

< 0.001

|

3065 (1366 to 4763)

|

< 0.001

|

|

Admitted from nursing home

|

−4.0 (−13.2 to 5.3)

|

0.404

|

6953 (−14 912 to 28 819)

|

0.533

|

|

History of falls on admission

|

−0.4 (−2.1 to 1.3)

|

0.659

|

−3778 (−7787 to 231)

|

0.065

|

|

|

∗The intraclass correlation coefficient was 0.002 for the number of falls (95% CI, 0.000–0.005) and 0.001 for number of fall injuries (95% CI, 0.000–0.003). †Elixhauser comorbidity method.14

|

Box 6 –

Adjusted increases in hospital length of stay (LOS) and costs associated with each additional fall (total study cohort)

Box 7 –

Adjusted increases in hospital length of stay (LOS) and costs associated with each additional fall injury (faller cohort only)

more_vert

more_vert