Australians living in rural areas have poorer oral health than city residents.1 They experience higher rates of dental caries2 and are more likely than people in city areas to visit dentists for problems other than check-ups.3 Complicating this situation is the inadequate availability of dental care services in rural areas because of the uneven distribution of dental practitioners across Australia; most dentists and other dental practitioners practise in city areas.4,5 Many small rural towns in Australia do not have the population to support a full-time or resident dentist. Dental services in Australia are largely provided by the private sector (85%);6 public oral health services are provided only for those under 18 years of age and for adults who hold health care concession cards.7

People on low incomes who cannot regularly access dental care and who do not have private insurance are more likely to present to general medical practices and hospital emergency departments with oral health problems for immediate treatment and referral.8–13 It is concerning that dental conditions accounted for 63 000 avoidable hospital admissions in Australia during 2012–13.14 The admission rates for these conditions were lowest among city residents (2.6 admissions per 1000 population) and highest for very remote residents (3.7 per 1000),15 although the rates in each category vary between jurisdictions.16

When dental services are not available in remote areas, people visit non-dental health providers, including medical staff, for dental care.12 Although rural general practitioners see patients with dental health problems, there has been limited research into their views about oral health. Our study investigated how rural GPs manage presentations by patients with oral health problems, and their perspectives on strategies to improve oral health in rural areas.

Methods

This study forms part of a broader oral health rural workforce research project that is investigating the relationship between dental practitioners and primary care networks. The chief dental officers of Tasmania, Queensland and South Australia were invited to identify rural and remote communities in which oral health care was a significant problem, and where there was at least one general medical practice, a health care facility and a pharmacy, but no resident dentist. Primary care providers in selected communities who had experience in advising patients with oral health problems were invited to participate in semi-structured interviews. Participants were recruited using both purposive and snowball sampling strategies.17

The interview guide was developed on the basis of our review of the relevant literature, and included questions about each participant’s professional background; the frequency and management of oral health presentations, and the level of confidence with which the practitioners managed these patients; and their views on strategies that could improve rural oral health. The interviews were conducted in the participants’ workplaces by one or more members of the research team between October 2013 and October 2014. Recruitment continued until data saturation18 was attained in the concurrent data analyses. Interviews were audio-recorded and later transcribed.

Interview data were subjected to thematic analysis.19 NVivo version 10.0 (QSR International) was used to organise transcripts and codes. All transcripts were verified against audio recordings by two members of the research team, and interview data coded independently for cross-validation. The coding results were compared and discussed at regular meetings involving all researchers until consensus was reached. The consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ)20 were used as a guide for ensuring quality. Quotes from individual GPs are identified in this article only by number (eg, GP 20).

Ethics approval for the study was granted by the Human Research Ethics Committee (Tasmania) Network (reference H0013217).

Results

Characteristics of study sites and participants

Sixteen communities were identified by state dental officers for inclusion in the investigation: three each in Tasmania and South Australia, and ten in Queensland. All but three Queensland communities were found to satisfy the study inclusion criteria (Box 1). In these communities, 101 primary care providers, including 30 GPs, participated in the study. In this article we report on the perspectives of these 30 GPs (18 from Queensland, nine from Tasmania, three from South Australia). Twenty-two were men, eight were women; 15 were 40 years old or younger, 15 were over 40 years old; the median time that the participants had worked in their current practice was one year (range, 0.04–35 years; interquartile range, 0.11–3.88). Nine GPs participated in two group interviews and 21 in individual interviews. Interviews lasted 30 to 60 minutes.

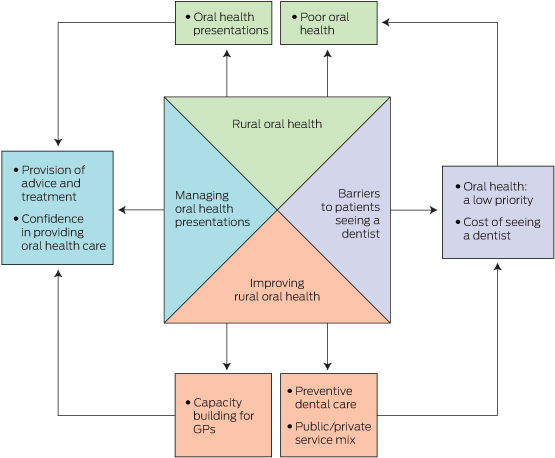

Four themes emerged from the interviews: rural oral health; managing oral health presentations; barriers to patients seeing a dentist; and improving oral health (Box 2).

Rural oral health

Participants reported seeing between one and 20 patients of various ages with oral health problems each month (mean, 12 per month for each community):

… the guy that just walked out and the one before him just walked out with a dental problem and probably three others came in today … four to five per week, close to 20 a month. (GP 10)

The oral health problems they saw ranged from toothaches, abscesses, oral infections and dentures to trauma:

… mostly what we see is dental abscesses, mouth ulcers, sometimes it is dentures … And, of course, extreme pain and tooth abscesses. (GP 8)

Having seen patients with oral health problems, GPs could observe the oral health status of their communities. Nine of 30 GPs commented that it was “so bad”, “very poor”, “never expected”, or even “shocking”:

I mean this town has shocking, shocking dental care … I’ve never seen teeth so badly decayed. (GP 10)

Managing oral health presentations

Most participants provided prescriptions for antibiotics and short-term pain relief, and advised patients to see dentists:

… if I suspect infection I will give antibiotics … As far as pain goes, I will give them a short-term oral pain relief … but I always give advice to go to the dentist. (GP 13)

Some also reported providing education about oral hygiene and preventive dental care:

I mostly provide pain relief, provide antibiotics, provide advice in personal dental care, I’m very hot on that. (GP 10)

Other treatments include dental block injections and tooth extractions:

Occasionally I pull people’s teeth here, but I’d rather not do it. (GP 19)

Eighteen of the GPs were confident, within their scope of practice, about providing oral health care advice and treatment:

Yes, pretty confident with basic dental emergency relief. (GP 4)

However, some acknowledged that they were not always confident, and that they lacked training in the area:

I start off … “sorry, I’m not a dentist”, and all I know is there are supposed to be 32 teeth in the mouth and that is pretty much all I know. I don’t have the training, absolutely not. (GP 6)

Barriers to patients seeing a dentist

Participants expressed concern that, for a number of reasons, patients would often not visit a dentist as advised. Some believed that this was because oral health was a low priority for these patients and this started with the parents:

Dental care is not a priority in rural people’s lives — at all … There are some quite attractive young men and women who’ve got shocking teeth … so just for lack of care … But again, it’s parental priority. When I was a kid, I come from a large family, my memory of school holidays was twice a year mum driving to a dentist. That was in the day with the old dentist drill with the black rubber bands … drilling … terribly slow … but we still used to go, we didn’t have a choice. But it’s my parents drove that, and they didn’t have a lot of money to spare, but they saw it as a priority. (GP 19)

As a consequence, some patients returned to the GP with even worse problems that required hospitalisation:

… the pain goes away and they don’t go to the dentist, and then they come back with chronic infection, and I say, “but I told you to go to the dentist” … lots of repeat clients. (GP 7)

Dental problems become medical problems if not treated and [we] need to admit them to hospitals. (GP 3)

Participants also noted that those on low incomes who did not have health care cards could often not afford to see a dentist regularly:

… the other thing that really is a big hindrance for oral health is the cost of going to the dentist, so a lot of people aren’t really going … [not] willing or are able to do that. I know I haven’t been to a dentist for a long time. (GP 20)

In the absence of a resident dentist or regular visits by mobile dental services, both public and private patients needed to travel to a larger centre to obtain dental care. This was described as “quite hard” and a “dilemma” for rural residents. A very remote GP reported:

I think the major issue for most of our patients is cost issues [involved in] flying off the island … so it’s the dilemma we face as professionals, as practitioners, as well as our patients. (GP 8)

Improving rural oral health

GPs suggested a number of ways to improve oral health in their rural communities. This included additional training in dental care on topics such as “major trauma interventions”, and more “practical advice”:

… we don’t really learn any dentistry at all … it’s still part of the body and doctors just kind of bypass it. (GP 20)

… I suppose we have to do what is best for our patients, and if we can in any way up-skill, upgrade our scope of practice in terms of dental care delivery, I’m happy to consider that. (GP 8)

Being busy clinicians in a small town, most GPs preferred flexible education and training, such as short online courses and workshops.

… the problem is I went to this course, had a great time, bought the kit, came back, never used it and then I’ll forget it! … it has to be regular, annual or semi-annual. (GP 19)

Spending some time at a dental clinic was also regarded as very beneficial:

I spent a day there [at a dental clinic] to have a look at what they did … It was a really helpful day … And because you have a friendly relationship, I can say OK, I am flicking [patients with dental problems] your way. (GP 15)

Twelve participants described the importance of community- and school-based oral health promotion:

Oral health education for the public should be better. Mum and Dad don’t brush their teeth, so the kids don’t do it either. (GP 2)

I really feel that having someone locally doing preventative health advice, especially with the children, checking that the fluoride is enough, a lot of our patients use tank water and they are not getting possibly the fluoride they need. Getting the paste on their teeth on a regular basis I think would make a big difference; just educate them. (GP 7)

Some saw opportunities to provide preventive advice to patients when they came for medical appointments:

I tell people routinely, but it’s part of the whole general holistic approach in general medicine. (GP 19)

Both public and private visiting oral health services were regarded as valuable for the community. A strategy suggested by 12 participants was to have a resident or visiting dentist or dental practitioner who could serve both public and private patients. This model was described by one GP as “half public and half private”:

We’d like an adult dentist please! On a regular basis and not just from the public system. It would be useful if there was someone out here that did private patients, so that people are not more disadvantaged who can’t get to town, and can’t get in if they don’t have a health care card. (GP 12)

GPs were not well informed about visiting dental services.

The private dentist comes when he comes … I don’t know why the hospital and doctors don’t know when the government dentist is coming. (GP 9)

Some GPs expressed concerns about the lack of a clear referral pathway to dentists, describing the communication as “one-way”; “nothing comes back”, “[we] never get feedback”:

There is no follow-up there, most of the time the dentist does not really send you anything back. Usually when I refer patients, you get more feedback, but I don’t get that from dentists. To be honest, the professional interaction coordination between me and most dentists, as a GP and the dentist, is nothing. (GP 11)

Only one GP reported receiving feedback from a dentist to whom he referred patients:

So if I refer someone to a dentist … I’ll write a letter to them and they’ll write back to me. (GP 19)

Discussion

We found that residents of the communities we sampled presented to GPs with oral health problems. Consistent with other reports,9,12,22 management of these problems by GPs typically included short-term pain relief, prescribing of antibiotics, advice that the patient see a dentist, and, if required, hospitalisation. GPs raised concerns about repeatedly seeing patients who did not visit a dentist as advised, and they referred to the relatively low priority given by many patients to oral health, as well as to cost and travel distances as major barriers to patients visiting a dentist. A number of presentations that required hospitalisation could have been averted by following the GPs’ advice. Participating GPs were therefore conscious of the need in their communities for broader oral health education and for promotion measures that would involve a range of health care professionals linking with other stakeholders. These measures include the delivery of regular oral health promotion programs in schools, reinforcement of good oral hygiene practices by parents, and fluoridation of town (or tank) water supplies where this was not currently undertaken.23 As primary care providers, GPs could play a critical role in providing oral health screening and education during their regular interactions with patients.

The interviewed GPs recognised that building their capacity and confidence could help them better care for patients with oral health problems. This might be achieved through regular short workshops on practical skills, training for dental emergencies,24,25 undertaking training modules, and consulting practice guidelines, including those available from the Royal Australian College of General Practitioners, the Australian College of Rural and Remote Medicine and the Royal Flying Doctor Service. These could be included in the induction process for GPs working in more isolated practice settings.

Participants expressed concerns about the lack of information about the dental services that visited their towns and the dearth of feedback from dentists about patients they had referred to them. Changes in professional and medical personnel and to visiting dental services, often attributed to funding cuts, compounded this problem. For the communities sampled in this study, there was clearly a need to establish effective communication and referral pathways between GPs and members of the dental teams.

In the absence of a universal dental health insurance scheme, some GPs recognised the opportunity for developing alternative business models for delivering dental services. For example, a mixed public/private funding model could enable dentists to provide services to both public and private patients in smaller communities in a financially viable and ethical manner. The potential of tele-dentistry to connect the GP with a dentist located elsewhere could also improve care for patients26 and help reduce the costs and burdens to patients of travel to regional centres for dental care.

A limitation of our study was the fact that 14 of the 30 GPs interviewed had worked in their communities for less than a year. This may have affected their answers to some questions, including those about communicating with the dental team. However, their responses were consistent with those of participants who had worked in their communities for longer periods, which suggested that this was a common problem, regardless of time in the current location. Further, we did not specifically recruit GPs from Aboriginal health centres, and our data were not verified against the records of dentists who had worked in the region. Finally, although we achieved data saturation, not all problems experienced by GPs may have been identified; different concerns might perhaps have emerged in other settings and in specific population groups.

Nevertheless, this study was unique in that it included a diverse sample of communities across three states and a relatively large number of GPs. This study contributes to our understanding of the experiences of GPs with respect to oral health in rural communities, and canvassed a number of strategies for improving the situation.

Rural oral health could be improved by a number of approaches, including building the capacity of GPs to assist people with dental health problems, strengthening community and individual engagement with oral health promotion and prevention activities, improving visiting dental services for all remote residents, regardless of whether they hold health care cards, and establishing more effective referral and communication pathways between dentists and GPs.

Box 1 –

Characteristics of the communities including in the study

|

Town

|

Population

|

Nearest dental surgery

|

Visiting dental service

|

ASGC-RA

|

|

|

1

|

< 500

|

248 km

|

Public dentist: once every 3 months; school dental van: sporadic visits

|

RA5

|

|

2

|

< 1000

|

70 km

|

No visiting oral health services

|

RA4

|

|

3

|

< 1000

|

40 km

|

School dental van: sporadic visits

|

RA3

|

|

4

|

< 1000

|

87 km

|

Private dentist: once a month

|

RA4

|

|

5

|

< 1000

|

179 km

|

Public dentist: once a year

|

RA5

|

|

6

|

< 1000

|

210 km

|

Private and public dentist visits: once every 3 months; mobile Aboriginal dental van: once a year; school dental van: sporadic visits

|

RA5

|

|

7

|

> 1000

|

43 km

|

No visiting oral health services

|

RA4

|

|

8

|

> 1000

|

40 km

|

No visiting oral health services

|

RA3

|

|

9

|

> 1500

|

214 km

|

Private dentist: once a month for 3 days; school dental van: sporadic visits

|

RA4

|

|

10

|

> 1500

|

212 km

|

Public and private dentists: sporadic visits

|

RA5

|

|

11

|

> 1500

|

200 km

|

Private dentist visits: once a month; school dental van: sporadic visits

|

RA5

|

|

12

|

> 2000

|

62 km

|

Private dentist visits: once a year

|

RA3

|

|

13

|

> 3000

|

196 km

|

Public dentist visits: once a month; mobile Aboriginal van: once a year

|

RA4

|

|

|

ASGC-RA = Australian Standard Geographical Classification Remoteness Area.21

|

Box 2 –

Thematic representation of general practitioners’ perspectives on rural oral health

more_vert

more_vert