Major changes will occur in the Australian National Cervical Screening Program (NCSP) from 2017, following an extensive review (“Renewal”).1 In addition to a re-designed mainstream program (5-yearly human papillomavirus [HPV]-based screening with partial genotyping; colposcopy referral for women testing positive for HPV16/18; liquid-based cytology [LBC] triage for other oncogenic HPV types), it was also recommended that HPV testing on self-collected cervico-vaginal samples (“self-collection”) be funded for unscreened and underscreened women.2 Self-collection must be facilitated by a clinician who also offers mainstream cervical screening, and is likely to be restricted to women aged 30–74 years who have never been screened or are overdue for cervical screening by 2 years or more.3

Offering self-collection has increased screening participation among unscreened and underscreened women in several settings,4 and is seen as a potentially useful strategy for extending cervical screening to previously hard to reach groups. It is being introduced for this purpose in several countries, including the Netherlands.5–7 Recent international reviews have reported that HPV testing on self-collected samples was somewhat less sensitive for high grade cervical abnormalities than testing on clinician-collected samples if signal-based tests are used; however, sensitivity was similar when using polymerase chain reaction (PCR)-based tests.8,9 These findings describe a range of possible test performances for self-collection, but they cannot be applied to specific technologies in the Australian context: here the performance measures and standards for HPV test platforms to be used as part of the population screening program will need to meet National Pathology Accreditation Advisory Council requirements.

Taking all of these factors into consideration, the aim of our study was to inform decision making by women offered self-collection in Australia by quantifying how different screening decisions affect the future risk of cervical cancer in previously unscreened women.

Methods

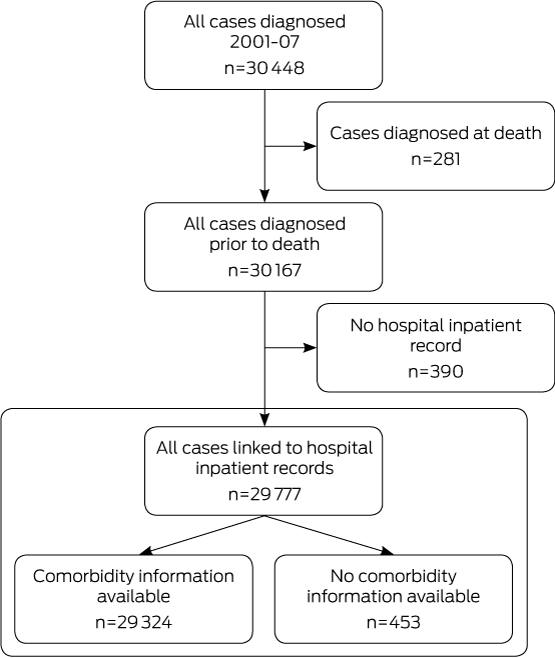

We used a dynamic model of HPV transmission and vaccination in conjunction with a cohort model of HPV natural history, cervical screening, diagnosis, treatment, and cancer survival. This model platform underpinned the Renewal review, and has been described in detail elsewhere.10 Dynamic models are considered the most comprehensive models of HPV epidemiology, as they incorporate the direct and indirect effects of HPV vaccination on the incidence of infection, and thus reflect its full impact on changes in risk. Model-predicted outputs have been extensively calibrated and validated against local cancer and pre-cancer outcomes by age and HPV type, resource use, and observed effects of HPV vaccination.10,11 Detailed clinical management pathways were informed by an expert advisory panel convened for the Renewal review.1,10

Model scenarios

We evaluated three choices that could be made by previously unscreened women:

-

a single round of HPV testing on a self-collected sample (“1 × self-collected”);

-

a single round of HPV testing on a clinician-collected sample (“1 × clinician-collected”); and

-

joining the mainstream screening program (5-yearly HPV-based screening with partial genotyping for HPV16/18 and LBC triage for other oncogenic HPV types; testing on clinician-collected samples) (“join the program”).

The comparator in all cases was choosing to remain unscreened. In the single screening round scenarios (the first two options), women were assumed to complete a single round of screening, but then to never re-attend for subsequently recommended rounds. We considered a round of screening to be completed if the women were HPV-negative on their primary screening test, or if they were HPV-positive but had subsequently undergone appropriate follow-up and had then been recommended to return to routine screening. The main analysis evaluated outcomes based on a decision taken at age 30 years, as this is the earliest age at which self-collection will be offered to most women, but we also considered the outcomes if the decision was deferred to age 40 or 50 years.

Since the intention was to provide information useful to women when making their decision, we assumed that those who elected to undergo screening would attend for all subsequently indicated tests and procedures, including LBC triage (an additional visit is required, as LBC cannot be performed on a self-collected sample), colposcopy, and treatment. In a sensitivity analysis, we examined imperfect compliance with the recommended follow-up (Appendix, section 3).

Test characteristics

The characteristics of HPV testing on self-collected samples (baseline and feasible range) were informed by a recent meta-analysis of performance relative to clinician-collected samples8 (Appendix, section 2.1). We took a conservative approach and considered a performance range based on international data relevant to various test technologies.7 In the baseline analysis, we assumed that self-collected samples would be tested for any oncogenic HPV type. In a sensitivity analysis, we evaluated the use of a clinical test with partial genotyping on these samples, allowing differential management of women who test positive for HPV16/18, consistent with the mainstream screening program and an Australian trial of self-collection.12 The characteristics of other tests used were informed by meta-analyses, and by colposcopy test data from Australia and England (Appendix, sections 2.2–2.4).

HPV vaccination

The baseline analysis estimated outcomes for women in the absence of HPV vaccination, which would be relevant for older women; however, in a secondary analysis we also considered outcomes for a cohort of women offered vaccination against HPV16/18 at age 12, as currently implemented in Australia. Estimates of the uptake of vaccination by these girls (72%) and by older females (included to capture the indirect effects of the catch-up program) were based on published data.13,14 National uptake data for males (included to capture the indirect effects of the program) were not yet available, so we assumed an age-specific uptake by those offered vaccination since 2013 equivalent to that achieved among females, based on initial state-based reports.15 Results for cohorts offered vaccination would be relevant to women in Australia who turn 30 years of age from around 2026 (who were offered HPV vaccination at age 12), but are also potentially useful for those who turn 30 from 2017 onwards (who were offered vaccination when aged 13–20 years; since some will have been exposed to HPV prior to vaccination, their absolute risks of developing cervical cancer will be slightly higher than for those offered vaccination at age 12).

Outcomes assessed

We estimated for a cohort of 100 000 previously unscreened women aged 30 years the cumulative numbers of incident cervical cancer diagnoses, cervical cancer deaths, and women ever treated for cervical pre-cancer to age 84 years. The number of women needing to be treated for cervical pre-cancer (NNT) to avert one cancer diagnosis (or one cancer death), compared with women who remained unscreened, was also calculated as a measure of the balance between the benefits and harms of screening.

Sensitivity analyses

In addition to those previously discussed, we also performed sensitivity analyses of several parameters that were previously found to be the most influential across a range of screening evaluations using our model, as well as of those parameters for which the value was most uncertain (Appendix, section 1).10,16 These included the accuracy of triage testing with LBC, the diagnostic accuracy of colposcopy, and the management of women who test positive for oncogenic HPV types other than 16/18 at the primary test and whose LBC triage test is low grade (“intermediate risk”; 12-month recall v colposcopy referral).

Ethics approval

This model-based study did not involve human participants, so ethics approval was not required. A number of de-identified datasets were used in the prior development and calibration of the model platform that was used for this evaluation. Ethics approval for the use and analyses of these datasets to inform the model was provided by the Cancer Council NSW Ethics Committee (references 232, 236) and by the University of New South Wales Human Research Ethics Committee (references HC13270, HC13349).

Results

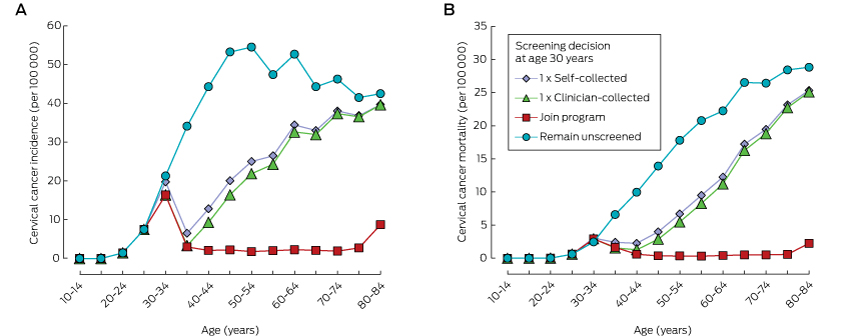

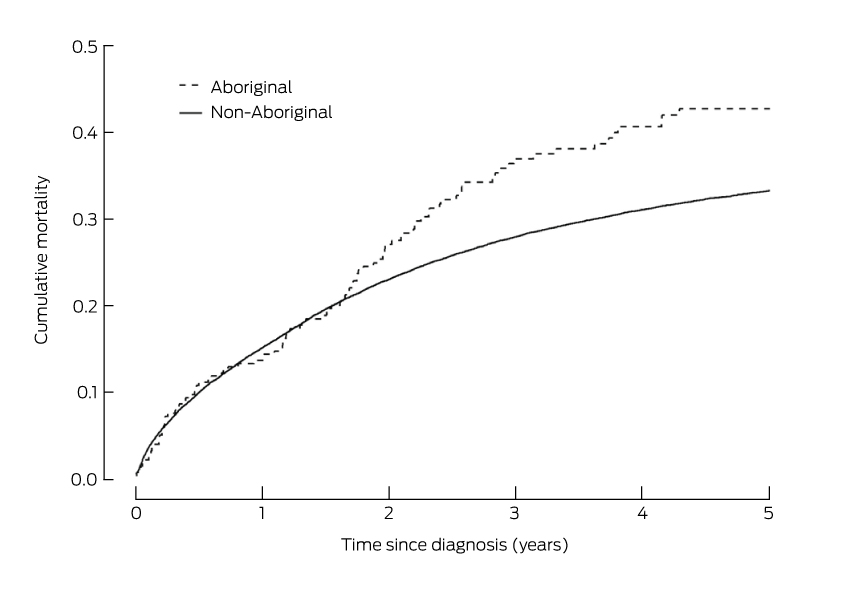

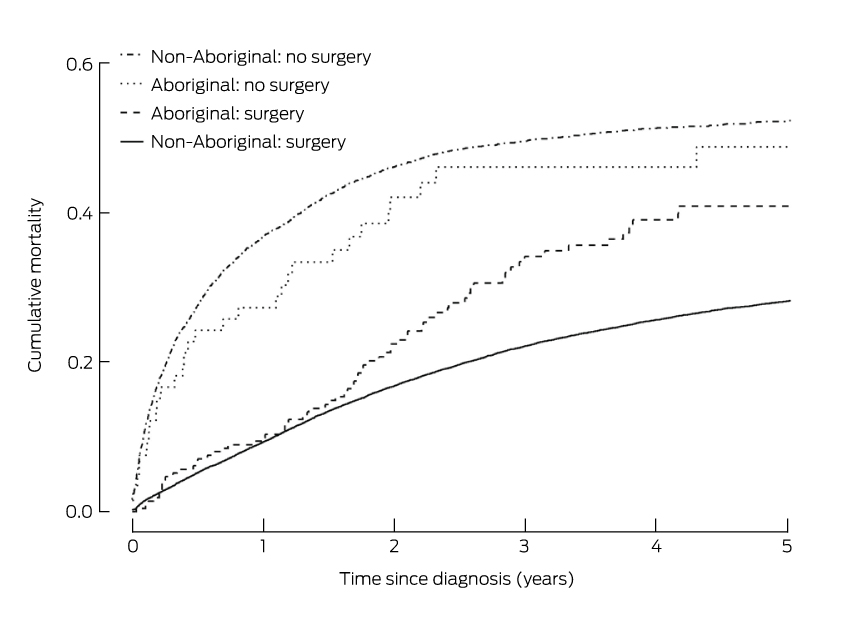

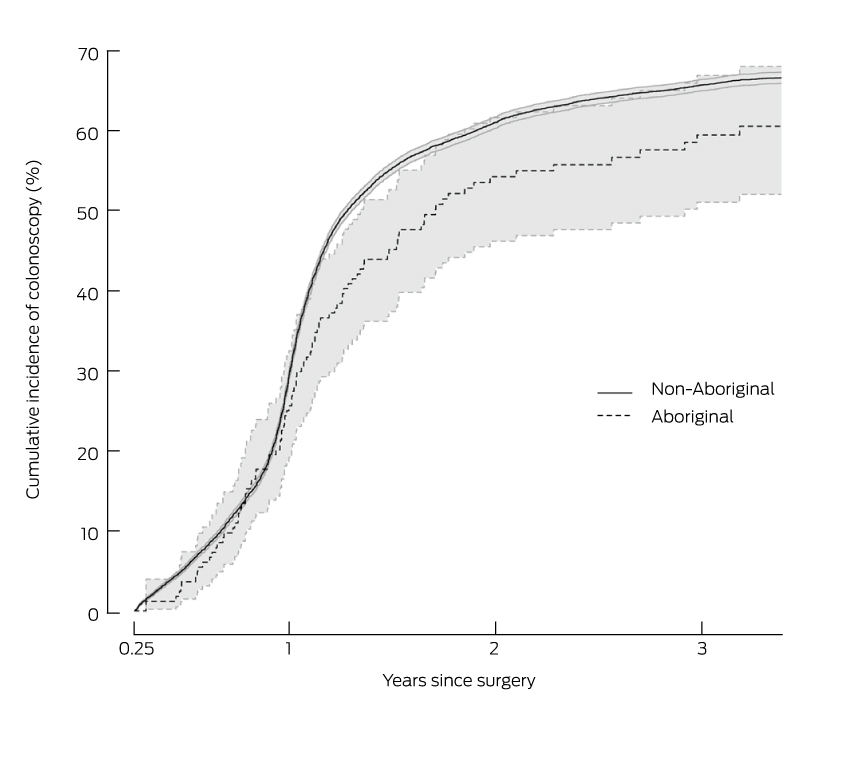

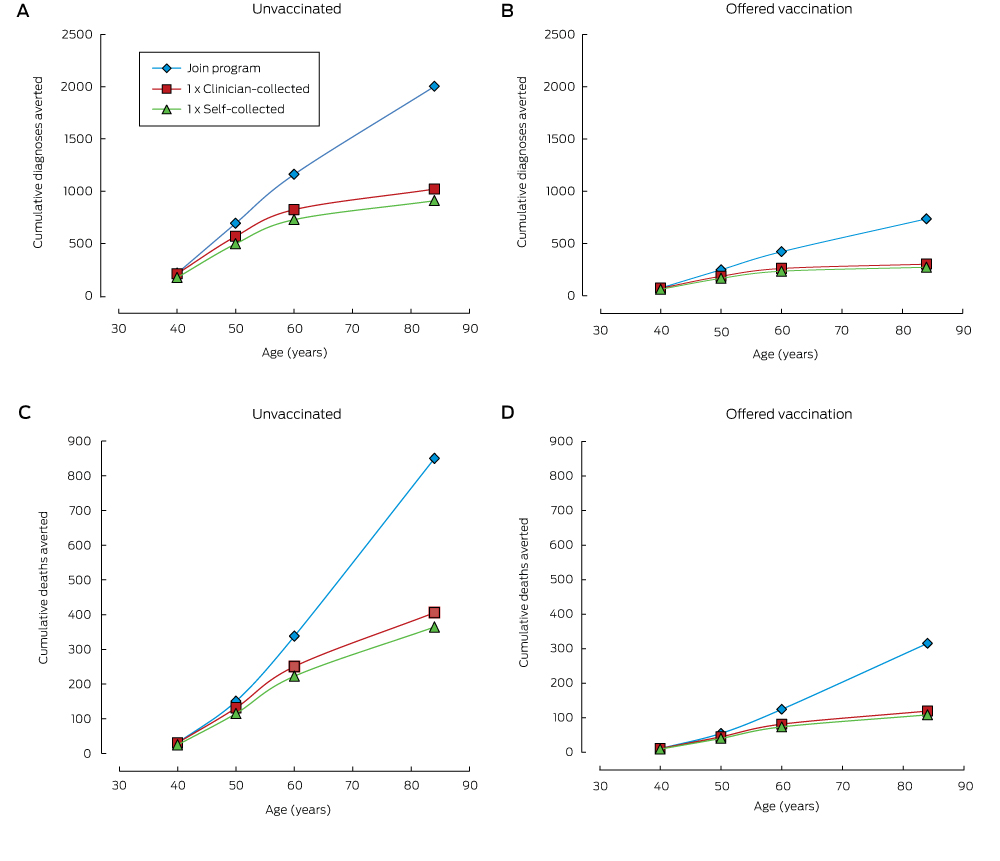

Compared with remaining unscreened, a single screening round at age 30 substantially reduced cancer incidence and mortality, and the number of cancer cases or deaths averted continued to increase over a woman’s life (Box 1, Box 2). One round of self-collected sample HPV screening in 100 000 women aged 30 years would avert 908 cancer diagnoses and 364 cancer deaths by age 84 (NNT, 5.8). Over a lifetime, the number of cancer cases or deaths averted by joining the mainstream program at age 30 years was about double that associated with a single screen at the same age. Underlying these findings is the fact that cancer incidence and mortality both start to increase again about 10 years after a single screen at age 30 years, whereas the lower incidence rate is maintained for most of a woman’s life if they join the program (Box 3). Joining the program was associated with the lowest NNT to avert each cancer case or death over a lifetime.

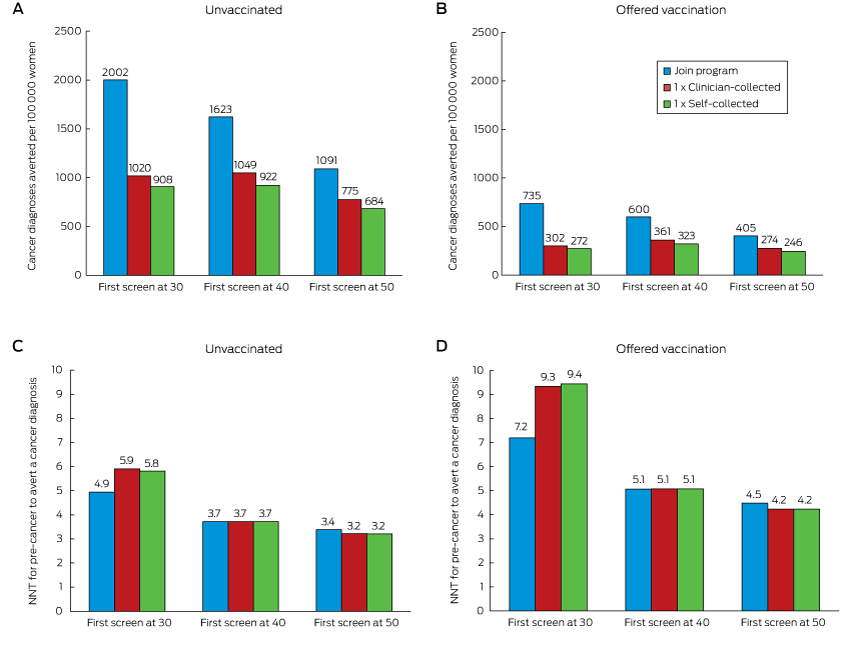

When the screening decision was deferred until age 40 or 50, the reduction in cancer diagnoses and deaths remained greatest when a woman joined the mainstream screening program; even doing so at age 50 averted more cases than a single screening round at age 30 or 40 (1091 fewer diagnoses and 583 fewer deaths [NNT, 3.4] by joining the program at age 50 v 908 or 922 fewer diagnoses and 364 or 426 fewer deaths [NNT, 5.8 or 3.7] for a single round of self-collection at ages 30 or 40 respectively). For each sample type, a single round of screening at age 40 prevented more cervical cancer cases and deaths than a single round at either age 30 or 50 (for self-collection, a single round of screening at ages 30, 40 or 50 years resulted in 908, 922 and 684 fewer diagnoses and 364, 426 and 385 fewer deaths respectively; for a clinician-collected sample, in 1020, 1049 and 775 fewer diagnoses, and 406, 480 and 437 fewer deaths respectively) (Box 4). While having a first screen at older ages often reduced the number of cases averted, the NNT to avert a cancer case was also lower.

Relative reductions in the numbers of cervical cancer diagnoses and deaths were similar for women in cohorts offered HPV vaccination and those who were not offered HPV vaccination. These reductions were substantial even when only one screening round was undertaken; however, the absolute numbers of diagnoses and deaths averted in those offered vaccination was smaller (by 63–70%) because of their lower underlying risk. In women offered vaccination, joining the program at age 30 averted more than twice as many cancer diagnoses and deaths as a single screen at the same age, and was also associated with a lower NNT to avert each cancer case (Box 2). Joining the program at age 50 remained more effective than a single screen at ages 30, 40 or 50 years (Box 4). At age 30, joining the mainstream program had the most favourable balance between benefits and harms; at older ages, the NNT was similar for all screening decisions. The NNT to avert a cancer diagnosis was 44–64% higher for women who had been offered vaccination than for those who were not (Box 4).

Sensitivity analyses

No feasible assumptions considered in sensitivity analysis altered the estimate of the number of diagnoses averted by more than 5%, or the NNT to avert a diagnosis by more than 8% (supplementary figures 3 and 4 in the Appendix). Results for self-collection were most sensitive to the accuracy of the HPV test and the availability of partial genotyping for HPV16/18. The effectiveness of joining the mainstream program was most sensitive to women’s compliance with the recommended tests, whereas the effect of this on single screening round scenarios was smaller (further discussion in the Appendix, section 5).

Discussion

This study provides valuable information that can inform decision making by women and clinicians. Even a single round of HPV screening on a self-collected sample can reduce the lifetime risk of a cervical cancer diagnosis, by around 41% if performed at age 30 or 40 years. A single round of HPV testing on a clinician-collected sample may offer superior results, but it is possible that the difference in outcomes may be smaller if a sufficiently accurate HPV test is used and if partial genotyping is performed on self-collected samples. However, our results also indicate that joining the mainstream program, even at an older age, offers substantially greater protection. Our findings also help to quantify the benefit for women of joining the program rather than being screened only once. For example, the benefit for women who continue to attend for recommended screening after a first screen at the age of 30 years is about double that of undergoing a single round of screening at 30. The balance of benefits and harms associated with joining the mainstream program was more favourable than or similar to that for a single screening round at all ages we considered in this analysis.

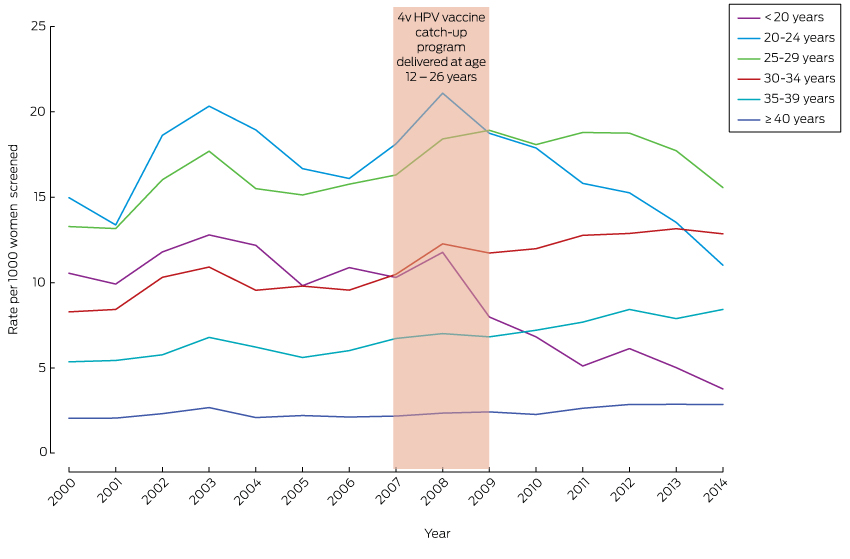

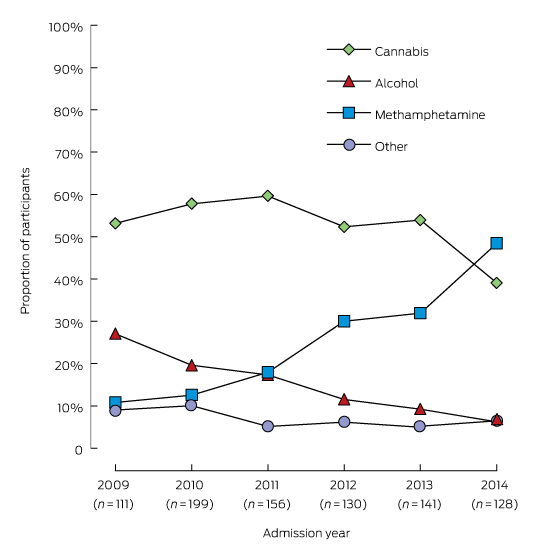

Self-collection was recommended during the Renewal review in the context of several factors in Australia. First, the 2-yearly cervical screening participation rate had remained relatively stable at around 60% for more than a decade, and the proportion of women remaining unscreened after 3 (almost 30%) or 5 years (about 17%) had also not decreased. Second, cervical cancers were mostly diagnosed in women who were unscreened or had not been screened in the previous 3.5 years (45% and 23% respectively of diagnosed invasive cancers in 2012).17 Third, there were persistent disparities in screening participation, with lower participation rates in lower socio-economic groups, among Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islanders, and in some migrant groups, and these participation disparities were reflected in the incidence of cervical cancer.18–22 These factors suggested that infrequent or non-participation in screening was a major barrier to further reducing the incidence of cervical cancer (which had plateaued over the past decade), and was also driving some persistent inequalities in cervical cancer incidence. Consequently, ensuring that all Australian women have access to a program that is acceptable, as well as effective and efficient, was a fundamental aim of Renewal.11 Self-collection is specifically aimed at women who are unscreened or underscreened.2

Two recent studies in Victoria suggested that self-collection is likely to be acceptable among women who are not being screened regularly, although, as both involved a mail-out model, their findings are not directly comparable with the NCSP recommendations. The iPap trial compared participation by previously unscreened and underscreened women who were randomly assigned to receiving either a mailed-out self-collection kit or a screening reminder letter.12 Offering self-collection was more effective in increasing participation than a reminder; attendance for recommended follow-up tests was high among women who returned a self-collected sample in the iPap trial; and participants reported finding self-collection simpler, more comfortable and less embarrassing than their previous Pap test (personal communication, Dorota Gertig, Medical Director, Victorian Cervical Cytology Register, July 2015). Secondly, a telephone survey in which women were asked about the option of home-based self-collection found that almost two-thirds of women who were unscreened or underscreened preferred this option to clinician-collected samples.23 Time since the most recent cervical screening test was the only significant factor associated with a preference for self-collection, with women who were up to date with screening less likely to prefer self-collection (27%) than women who had never been screened (62%; odds ratio [OR], 4.16; P < 0.001) or had not been screened in the previous three years (65%; OR, 5.19; P < 0.001). Women who did not favour self-collection most commonly cited a preference for seeing a general practitioner and a lack of confidence in their ability to collect the sample properly. This suggests that the model proposed for the NCSP, where self-collection is facilitated by a practitioner who also performs mainstream screening, is appropriate, as women may be reassured about their ability to perform the test by the facilitating provider or elect to have their practitioner collect a sample. However, some of the women who are currently less likely to participate in screening, including Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander women, migrants, and those from lower socio-economic groups, were under-represented in the survey.

One concern about self-collection is that women who currently attend the mainstream program may switch to self-collection, and this could lead to a less effective program overall. The proposed model of restricting self-collection through a screening provider to under- and unscreened women is designed to reduce this problem. The results from our study provide additional information for both the provider and the woman by quantifying both the benefit of self-collection for unscreened women and the additional benefit of remaining in the mainstream program. Findings from a recent modelling study in the Netherlands suggest that, to maintain the overall effectiveness of a program including targeted self-collection, it is crucial that women at the greatest risk are among those who adopt self-collection and that a sufficiently accurate test is used.24 Our results also underline the importance of using a sufficiently accurate test and partial genotyping for HPV16/18 for ensuring comparable long term cancer outcomes in self-collected and clinician-collected samples.

The strengths of this study include the use of a robust model that has been calibrated against a large number of program outputs, and that clinical management pathways incorporated detailed local expert input.10 Another strength is that it included estimates for women offered vaccination during early adolescence, meaning the results will remain informative into the future. When self-collection first becomes available for unscreened women aged 30–74 years in 2017, the youngest women eligible will have been 20 years old when the HPV vaccination program commenced. A sizeable proportion of these women will have been vaccinated (30–63% with three doses),14 although possibly with lower effectiveness than in the cohorts modelled here.25 The absolute benefit of screening in these intermediate cohorts will potentially be slightly higher than for those offered vaccination at age 12, but our results suggest that the relative reductions are similar in both unvaccinated cohorts and those offered vaccination. Our results for cohorts offered vaccination will be fully applicable to women turning 30 from 2026.

As our results are intended to provide guidance for women and clinicians when making decisions, a limitation to our study is that compliance with recommended follow-up tests and procedures was assumed to be perfect. This assumption means our results cannot be directly interpreted as population-wide results; this was beyond the scope of the current study. However, trial data support the strong benefits we found from even a single screening round (further discussion in the Appendix, section 7), and these benefits did not vary substantially across the range of compliance assumptions examined. Self-collection at regular intervals was not evaluated, given the greater uncertainties in the evidence concerning the use of self-collection for routine screening, and because self-collection is not intended as a regular replacement for clinician-collected samples.

Our results support offering self-collection to women who are unscreened and reluctant to join the mainstream screening program, including older women, for whom the balance between benefits and harms remains very favourable. However, the level of protection achieved by joining the mainstream program and thereafter undergoing regular screening, even at older ages, is far greater. Engaging women and redressing barriers to their participation in the mainstream program must remain a primary focus.

Box 1 –

Impact of screening decision at age 30 years on the future risk of cervical cancer diagnosis and death, and treatment for pre-cancer, for a cohort of 100 000 previously unscreened women aged 30 years (unvaccinated cohort)

|

|

Number of women affected by cervical cancer, by age: |

||||||||||||||

|

40 years |

50 years |

60 years |

Lifetime* |

||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||

|

Cervical cancer diagnosis |

|

|

|

|

|||||||||||

|

Join program† |

99 |

120 |

139 |

205 |

|||||||||||

|

1 × clinician-collected |

104 |

245 |

476 |

1187 |

|||||||||||

|

1 × self-collected |

140 |

316 |

572 |

1299 |

|||||||||||

|

Remain unscreened |

312 |

811 |

1299 |

2207 |

|||||||||||

|

|

Relative risk reduction compared with remaining unscreened, by age: |

||||||||||||||

|

40 years |

50 years |

60 years |

Lifetime* |

||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||

|

Cervical cancer death |

|

|

|

|

|||||||||||

|

Join program† |

22 |

26 |

30 |

45 |

|||||||||||

|

1 × clinician-collected |

22 |

46 |

117 |

490 |

|||||||||||

|

1 × self-collected |

28 |

62 |

145 |

531 |

|||||||||||

|

Remain unscreened |

53 |

177 |

367 |

895 |

|||||||||||

|

Died from other causes |

488 |

1655 |

4195–4202 |

39 509–39 780 |

|||||||||||

|

Cervical cancer diagnosis |

|

|

|

|

|||||||||||

|

Join program† |

68% |

85% |

89% |

91% |

|||||||||||

|

1 × clinician-collected |

67% |

70% |

63% |

46% |

|||||||||||

|

1 × self-collected |

55% |

61% |

56% |

41% |

|||||||||||

|

Cervical cancer death |

|

|

|

|

|||||||||||

|

Join program† |

58% |

85% |

92% |

95% |

|||||||||||

|

1 × clinician-collected |

58% |

74% |

68% |

45% |

|||||||||||

|

1 × self-collected |

47% |

65% |

61% |

41% |

|||||||||||

|

|

Women ever treated for cervical pre-cancer, by age: |

||||||||||||||

|

40 years |

50 years |

60 years |

Lifetime* |

||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||

|

Join program† |

7373 |

8498 |

9143 |

9894 |

|||||||||||

|

1 × clinician-collected |

5973 |

6018 |

6019 |

6019 |

|||||||||||

|

1 × self-collected |

5235 |

5277 |

5278 |

5279 |

|||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||

|

* Until (and including) 84 years of age. † Five-yearly human papilloma virus (HPV)-based screening with partial genotyping; colposcopy referral for women testing HPV16/18 positive; liquid-based cytology triage for other oncogenic HPV types. |

|||||||||||||||

Box 2 –

Cumulative numbers of cervical cancer diagnoses (A, B) and deaths (C, D) averted in women screened for human papillomavirus (HPV) at age 30 (compared with remaining unscreened), by attained age, in unvaccinated women (A, C) and women offered vaccination at age 12 (B, D)

more_vert

more_vert