Familial hypercholesterolaemia (FH) is the most common autosomal dominant condition.1 FH reduces the catabolism of low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-c) and increases rates of premature atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease (CVD). This review focuses on recent advances in the management of FH, and the implications for both primary and secondary care, noting that the majority of individuals with FH remain undiagnosed.2

FH was previously considered to have a prevalence of one in 500 in the general community, including in Australia.3 Recent evidence, however, suggests the prevalence is between one in 200 and one in 350, which equates to over 30 million people estimated to have FH worldwide.4,5 These prevalence figures relate to the general population, and while FH is present in all ethnic groups, communities with gene founder effects and high rates of consanguinity, such as the Afrikaans, Christian Lebanese and Québécois populations, have a higher prevalence of the condition.

Further, the prevalence of homozygous or compound heterozygous FH has been demonstrated to be at least three times more common than previously reported, with a prevalence of about one in 300 000 people in the Netherlands.4 The detection and management of individuals with homozygous FH has been described in a consensus report from the European Atherosclerosis Society.6 Homozygous FH is a very severe disorder, with untreated people often developing severe atherosclerotic CVD before 20 years of age. Such individuals often have LDL-c concentrations > 13 mmol/L and severe cutaneous and tendon xanthomata. While diet and statins are the mainstays of therapy, early intervention (before 8 years of age) with LDL apheresis or novel lipid-lowering medication, such as proprotein convertase subtilisin/kexin type 9 (PCSK9) inhibitors or microsomal triglyceride transfer protein inhibitors, is indicated. Patients with suspected homozygous FH should be referred to a specialist centre.6

Several recent international guidelines on the care of FH have been published.3,7–10 These have focused on early detection and treatment of individuals with FH. However, there is still no international consensus on the diagnostic criteria for FH, or on the utility of genetic testing. The Dutch Lipid Clinic Network criteria (DLCNC) are preferred for diagnosing FH in index cases in Australia (Box 1).2 The International FH Foundation guidance acknowledges geographical differences in care, and recognises the need for countries to individualise service delivery. CVD risk in FH is dependent on classic CVD risk factors. However, FH is appropriately excluded from general absolute CVD algorithms, since these underestimate the absolute risk in FH.

FH guidelines provide therapeutic goals, which vary depending on the specific absolute CVD risk for patients with FH. In adults, the general LDL-c goal is a least a 50% reduction in pre-therapy LDL-c levels, followed by a target of LDL-c < 2.5 mmol/L, or < 1.8 mmol/L in individuals with CVD or other major CVD risk factors; these international targets update those of previously published Australian FH recommendations.2,3,10 Currently only about 20% of individuals with FH attain an LDL-c level < 2.5 mmol/L.11

Detecting FH in children

The European Atherosclerosis Society published a guideline focusing on paediatric aspects of the diagnosis and treatment of children with FH in 2015.8 This guideline outlined the benefit of early treatment of children with FH using statins. There is a significant difference in the carotid intima medial thickness (a measure of subclinical atherosclerosis) in children with FH and their unaffected siblings by 7 years of age, with implications for the value of early treatment. Lifestyle modifications and statins from 8 years of age can reduce the progression of atherosclerosis to the same rate as unaffected siblings over a 10-year period.8 Early treatment of children improves CVD-free survival by 30 years of age (100%) compared with their untreated parents (93%; P = 0.002).8 While further long term data on statin use in children are required, there are 10-year follow up data for children who were initiated on pravastatin between the ages of 8 and 18 years, which demonstrate that statin therapy is safe and effective.12 Hence, the balance of risk and benefit suggests that use of statins in children with FH is safe and efficacious, at least in the short to intermediate term, with all recommendations appropriately requiring that potential toxicity and adverse events be closely monitored.

Childhood is the optimal period for detecting FH, as LDL-c concentration is a better discriminator between affected and unaffected individuals in this age group. After excluding secondary causes and optimising lifestyle and repeating fasting LDL-c on two occasions, a child is considered likely to have FH if they have:

-

an LDL-c level ≥ 5.0 mmol/L;

-

a family history of premature CVD and an LDL-c level ≥ 4.0 mmol/L; or

-

a first-degree relative with genetically confirmed FH and an LDL-c level ≥ 3.5 mmol/L.

Universal screening for FH in children has been demonstrated to be effective in Slovenia, but experience is limited elsewhere.13 The therapeutic targets for children are less aggressive than for adults: a reduction in LDL-c of over 50% in children aged 8–10 years and an LDL-c level < 3.5 mmol/L from the age of 10 years.8

Cascade screening

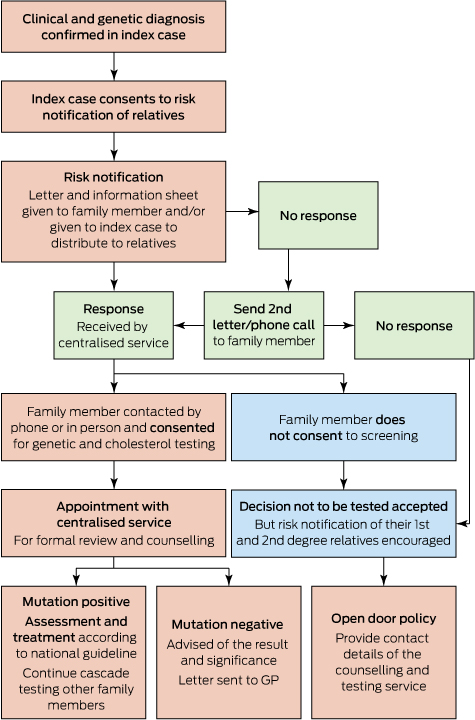

Recent reports from Western Australia confirm that cascade screening is efficacious and cost-effective.11,14 The genetic cascade screening and risk notification process followed in Western Australia is shown in Box 2.11 Cascade screening involves testing close relatives of individuals diagnosed with FH. The autosomal dominant inheritance suggests 50% of first-degree relatives would be expected to have FH. Two new cases of FH were found by cascade screening for each index case in WA.11 These individuals were younger and had less atherosclerotic CVD than index cases. Interestingly, about 50% were already on lipid-lowering therapy, but they were not treated to the recommended goals and further lipid reductions were achieved overall. Over 90% of patients were satisfied with the cascade screening process and care provided by this service .11 However, for individuals who have not had genetic testing performed, or for individuals with clinical FH in whom a mutation has not been identified, cascade screening should also be undertaken using LDL-c alone.

Although we have recently shown that genetic testing is cost-effective in the cascade screening setting ($4155 per life year saved),14 only a few centres in Australia have this facility and testing is currently not Medicare rebatable. However, combining increased awareness of the benefits of identifying people with FH with the reducing analytical costs may increase the use of genetic testing. This in turn could guide advocacy and lobbying Medicare to support genetic testing for FH.

Detecting FH in the community

A novel approach that utilises the community laboratory to augment the detection of FH has recently been tested in Australia. The community laboratory is well placed to perform opportunistic screening, since they perform large numbers of lipid profiles, the majority (> 90%) of which are requested by general practitioners.15 Clinical biochemists can append an interpretive comment to the lipid profile reports of individuals at high risk of FH based on their LDL-c results. These interpretive comments on high risk individuals (LDL-c ≥ 6.5 mmol/L) led to a significant additional reduction in LDL-c and increased referral to a specialist clinic.16 A phone call from the clinical biochemist to the requesting GP improved both the referral rate of high risk (LDL-c ≥ 6.5 mmol/L) individuals to a lipid specialist and the subsequent confirmation of phenotypic FH in 70% of those referred, with genetic testing identifying a mutation in 30% of individuals.17 There is a list of specialists with an interest in lipids on the Australian Atherosclerosis Society website (http://www.athero.org.au/fh/health-professionals/fh-specialists).

In Australia, GPs consider they are the best placed health professionals to detect and treat individuals with FH in the community.18 A large primary care FH detection program in a rural community demonstrated that using pathology and GP practice databases was the most successful method to systematically detect people with FH in the community.19 However, a survey of GPs uncovered some key knowledge deficits in the prevalence, inheritance and clinical features of FH, which would need to be addressed before GPs can effectively detect and treat individuals with FH in the community.18 A primary care-centred FH model of care for Australia has recently been proposed to assist GPs with FH detection and management, but this requires validation.20 The model of care includes an algorithm that is initiated when an individual is found to have an LDL-c level ≥ 5.0 mmol/L, which could be highlighted as at risk of FH by either a laboratory or the GP practice software.20,21 The doctor is then directed to calculate the likelihood of FH using the DLCNC. Patients found to have probable or definite FH are assessed for clinical complexity and considered for cascade testing. See the Appendix at mja.com.au for the algorithm and definition of complexity categories. FH-possible patients should be treated according to general cardiovascular disease prevention guidelines.

Molecular aspects

There have also been advances in molecular aspects of FH. A recent community-based study in the United States confirmed that among patients with hypercholesterolaemia, the presence of a mutation was independently predictive of CVD, underscoring the value of genetic testing.22 The mutation spectrum of FH was described in an Australian population and was found to be similar to that in Europe and the United Kingdom.23 Mutation detection yields in Australia are comparable with the international literature; for example, 70% of individuals identified with clinically definite FH (DLCNC score > 8) had an identifiable mutation, whereas only 30% of those with clinically probable FH had a mutation.23

Polygenic hypercholesterolaemia (multiple genetic variants that each cause a small increase in LDL-c but collectively have a major effect in elevating LDL-c levels) is one explanation for not identifying an FH mutation. An LDL-c gene score has been described to differentiate individuals with FH (lower score) from those with polygenic hypercholesterolaemia (higher score), but this requires validation.24 About 30% of individuals with clinical FH are likely to have polygenic hypercholesterolaemia, and cascade screening their family members may not be justified.25

A further possible explanation for failure to detect a mutation causative of FH in an individual with clinically definite FH may lie in the limitations of current analytical methods such as restricting analysis to panels of known mutations. Further, FH is genetically heterogeneous and there may be unknown alleles and loci that cause FH. Next generation sequencing is capable of sequencing the whole genome or targeted exomes rapidly at a relatively low cost, and may improve mutation detection and identify novel genes causing FH, but further experience with its precise value in a clinical setting is required. Whole exome sequencing was able to identify a mutation causing FH in 20% of a cohort of “mutation negative” but clinically definite FH patients.25 However, when applied to patients with hypercholesterolaemia in a primary care setting, pathogenic mutations were only detected in 2% of individuals, with uncertain or non-pathogenic variants detected in a further 1.4%.26

Cardiovascular risk assessment

Absolute CVD risk assessment, employing risk factor counting, should be performed as atherosclerotic CVD risk is variable in FH.10,27 This involves appraisal of classic CVD risk factors including, age, sex, hypertension, diabetes, chronic kidney disease and smoking. The prevalence of classic CVD risk factors among Western Australians with recently identified FH was 13% for hypertension, 3% for diabetes and 16% for smokers, all of which were amenable to clinical intervention.11

Other non-classic CVD risk factors are also important for individuals with FH, especially chronic kidney disease and elevated levels of lipoprotein(a).28 Lipoprotein(a) is a circulating lipoprotein consisting of an LDL particle with a covalently linked apolipoprotein A. Its plasma concentration is genetically determined and it is a causal risk factor for CVD in both the general population and FH patients.29,30 Lipoprotein(a) concentrations are not affected by diet or lowered by statins.31

Management and new therapies

The past 2 years have also seen the development of new treatments for FH, but lifestyle modifications and statins remain the cornerstones of therapy for FH. Ezetimibe has been demonstrated to reduce coronary events against a background of simvastatin in non-FH patients with established CVD.32 PCSK9 inhibitors have recently been approved to treat individuals with FH or atherosclerotic CVD not meeting current LDL-c targets in Europe and America. PCSK9 is a hepatic convertase that controls the degradation and hence the lifespan of the LDL receptor. PSCK9 is secreted by the hepatocyte and binds to the LDL receptor on the surface of the hepatocyte. The LDL receptor–PCSK9–LDL-c complex is then internalised via clathrin-dependent endocytosis, but the PSCK9 directs the LDL receptor towards lysosomal degradation instead of recycling it back to the hepatocyte surface.33 A recent meta-analysis of early PCSK9 inhibition trials involving over 10 000 patients demonstrated a 50% reduction in LDL-c, a 25% reduction in lipoprotein(a), and significant reductions in all-cause and cardiovascular mortality.34

The PCSK9 inhibitors alirocumab and evolocumab were approved by the European Medicines Agency in 2016 for homozygous and heterozygous FH and non-FH individuals unable to reach LDL-c targets, and for individuals with hypercholesterolemia who are statin intolerant. In the US, the Food and Drug Administration has approved alirocumab for heterozygous FH and individuals with atherosclerotic CVD who require additional reduction of LDL-c levels. Evolocumab and alirocumab have recently been approved by the Therapeutic Goods Administration in Australia for people with FH. Adverse events are generally similar to placebo, but reported side effects include influenza-like reaction, nasopharyngitis, myalgia and raised creatine kinase levels, and there have been reports of neurocognitive side effects (confusion, perception, memory and attention disturbances).34 The cost of these agents is likely to be the major limitation to their clinical use. The indications and use of lipoprotein apheresis and other novel therapies, including lomitapide, a microsomal triglyceride transfer protein inhibitor, and mipomersen (an antisense oligonucleotide that targets apolipoprotein B), have been recently reviewed.35

Despite the advances reviewed, the implementation and optimisation of models of care for FH remain a major challenge for preventive medicine. Areas of future research should focus on better approaches for detecting FH in the young and on enhancing the integration of care between GPs and specialists. The value of genetic testing and imaging of pre-clinical atherosclerosis in stratifying risk and personalising therapy merits particular attention. Further, with families now living in a global community, more efficient methods of communication and data sharing are required. This may be enabled by international Web-based registries.36 Care for people with FH needs to be incorporated into health policy and planning in all countries.10

Conclusion

There have been significant advances in the care of individuals with FH over the past 3 years. An integrated model of care has been proposed for primary care in Australia. Progress has also been made in the treatment of FH with the emergence of PCSK9 inhibitors capable of allowing more patients already on statins to attain therapeutic LDL-c targets and hence redressing the residual risk of atherosclerotic CVD. Future research is required in the areas of models of care, population science and epidemiology, basic science (including genetics), clinical trials, and patient-centric studies.37 Finally, the onus rests on all health care professionals to improve the care of families with FH, in order to save lives, relieve suffering and reduce health care expenditure.

Box 1 –

Dutch Lipid Clinic Network Criteria score for the diagnosis of familial hypercholesterolaemia (FH)2

|

Criteria

|

Score

|

|

|

Family history

|

|

|

First-degree relative with known premature coronary and/or vascular disease (men aged < 55 years, women aged < 60 years); or

|

1

|

|

First-degree relative with known LDL-c > 95th percentile for age and sex

|

|

|

First-degree relative with tendon xanthomas and/or arcus cornealis; or

|

2

|

|

Children aged < 18 years with LDL-c > 95th percentile for age and sex

|

|

|

Clinical history

|

|

|

Patient with premature coronary artery disease (ages as above)

|

2

|

|

Patient with premature cerebral or peripheral vascular disease (ages as above)

|

1

|

|

Physical examination

|

|

|

Tendon xanthomata

|

6

|

|

Arcus cornealis at age < 45 years

|

4

|

|

LDL-c

|

|

|

≥ 8.5 mmol/L

|

8

|

|

6.5–8.4 mmol/L

|

5

|

|

5.0–6.4 mmol/L

|

3

|

|

4.0–4.9 mmol/L

|

1

|

|

DNA analysis: functional mutation in the LDL receptor, apolipoprotein B or PCSK9 gene

|

8

|

|

Stratification

|

|

|

Definite FH

|

> 8

|

|

Probable FH

|

6–8

|

|

Possible FH

|

3–5

|

|

Unlikely FH

|

< 3

|

|

|

LDL-c = low-density lipoprotein cholesterol. PCSK9 = proprotein convertase subtilisin/kexin type 9.

|

Box 2 –

Protocol for genetic cascade screening in Western Australia*

more_vert

more_vert