The known Treating patients with pancreatic cancer is challenging, and socio-demographic factors influence whether patients receive specific treatment forms, such as surgery and chemotherapy.

The new Our composite quality of care score was lower for patients from rural or socially disadvantaged areas; it was higher for patients who first presented to a hospital with a high pancreatic case volume. A higher score was significantly associated with improved survival.

The implications Strategies should be developed which ensure that all patients with pancreatic cancer have the opportunity to receive optimal care from or in conjunction with high pancreatic case volume centres.

In Australia, pancreatic cancer is the tenth most common cancer, and the fourth leading cause of cancer-related death.1 One-year survival is 20%, 5-year survival 6%.2 Treating pancreatic cancer presents distinctive challenges, and requires highly specialised care to achieve optimal outcomes.3 Studies in Australia and overseas have shown that fewer patients receive the recommended treatment than expected,4,5 that receiving recommended care is inconsistent,6,7 and that socio-demographic factors influence the treatment of patients with pancreatic cancer.7,8 Treating patients in non-specialised centres appears to at least partly explain these findings.9,10

Previous studies have tended to focus on individual types of treatment, such as surgery or chemotherapy. We took a more holistic approach and calculated an overall quality of care score for Australian patients diagnosed with pancreatic cancer. We examined variations in the score associated with patient and health service-related factors, and analysed the relationship between quality of care and survival.

Methods

This analysis was nested within a population-based study of patterns of care for patients in Australia with pancreatic cancer. Eligible patients were residents of Queensland and New South Wales diagnosed with pancreatic cancer between July 2009 and June 2011. Patients with histological confirmation of pancreatic adenocarcinoma were included, as were patients with presumed pancreatic cancer but without histological or cytological confirmation. Trained research nurses collected information about patient treatment from medical records in public and private facilities.4 Patients were excluded from this analysis if they died within one month of diagnosis or clinical staging data were unavailable.

We calculated a quality of care score based on the results of our previously reported Delphi process.11 Briefly, clinicians from a range of specialties involved in care for patients with pancreatic cancer were asked “What is important in the care of patients with pancreatic cancer?” A list of statements was prepared on the basis of a thematic analysis of the responses. The clinicians were asked to score each statement on a scale of 0 (“disagree”, “not important”) to 10 (“strongly agree”, “very important”). The mean score and the coefficient of variation (CV) were calculated for each statement.

Calculating the quality of care score

We calculated quality of care scores on the basis of the mean Delphi process scores, selecting statements about which there had been reasonable consensus in the Delphi process (CV ≤ 0.4) and when information for assessing whether the item of care had been delivered was available in our database. Eighteen items were included in the analysis (Box 1).

For each patient, we calculated a potential score by identifying the items that applied to their clinical situation and summing the mean scores from the Delphi survey for these items. For example, items related to surgical procedures were included only for patients who underwent attempted resection. We then identified items for which there was evidence that the specified care had been delivered and summed their mean Delphi scores as a score for care delivered. The proportional care score was calculated by dividing the care delivered score by the potential score, yielding a value between 0 and 1. The clinical information that determined eligibility and whether or not care specified by an item was delivered are shown in Box 1.

Measurement of potential determinants of care

Patient characteristics assessed included age, sex, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) performance status, and Charlson comorbidity index.12 Based on their area of residence at diagnosis, each person was allocated a socio-economic index for areas (SEIFA)13 score and Accessibility/Remoteness Index of Australia (ARIA+)14 category. We grouped the SEIFA scores into quintiles, and collapsed the ARIA into three levels: major city, inner regional, and rural (which included the outer regional, remote and very remote categories).

Tumour-related factors included the stage of the tumour, categorised as potentially resectable or not, and as confined to the pancreas, locally advanced, or metastatic.

Health service-related factors included the type of specialist first seen, and the number of pancreatic cancer presentations (volume) for the facility to which the patient first presented.

Statistical analysis

The proportions of eligible patients who received each item of care were calculated; the statistical significance of differences between proportions according to socio-economic status and place of residence categories was assessed in χ2 tests.

We used linear regression analyses, with the proportional score as the outcome, to examine variation in the score attributable to patient-, tumour- and health service-related factors. Mean proportional scores for levels of each exposure variable were calculated and β coefficients reported (with 95% confidence intervals [CIs]). The β coefficients were interpreted as the difference between the mean score for patients in a particular category and that of patients in the reference category. Multivariable models included age, ECOG performance status, and comorbidity score as factors.

Survival time was calculated from the date of diagnosis until the death of the patient or the date of the final follow-up (February 2014). Patients were grouped in quartiles according to their proportional care scores; Kaplan–Meier graphs were generated and log-rank tests assessed differences in survival according to score quartile. We also performed the analysis with the proportional care score as a continuous variable; we report changes in survival associated with each 10 percentage point increase in score, using Cox proportional hazard models to adjust for patient-related factors and clinical stage. The association between the score and survival was further investigated by calculating adjusted hazard ratios for each care score item separately. Analyses were performed for the entire patient group and separately for patients with or without metastases identified at clinical staging. We used Stata 14 (StataCorp) for all analyses. P < 0.05 (two-sided) was deemed statistically significant.

Ethics approval

Access to medical records was approved under the Queensland Public Health Act and the NSW Privacy Act. Ethics approval was obtained from the QIMR Berghofer Medical Research Institute (reference, P1292), the Royal Brisbane and Women’s Hospital (on behalf of all public hospitals in Queensland; reference, HREC/10/QRBW/16), and the NSW Population and Health Services Research Ethics Committee (reference, HREC/10/CIPHS/45).

Results

A total of 1896 patients were eligible for inclusion in the patterns of care study. We were unable to locate medical records for 33 patients; 259 had died within one month of diagnosis, and staging information was not available for 33, so that 1571 patients (83%) were included in our analysis, including 867 men (55%). At clinical staging, 781 patients (49.7%) had non-metastatic disease and 790 (50.3%) metastatic disease. Most patients lived in major cities (1076, 68%); 338 (22%) lived in inner regional areas and 157 (10%) in rural areas. Almost three-quarters of patients (1151, 73%) died within one year of diagnosis. The median survival time was 6 months (11 months for patients without metastases; 4 months for those with metastases).

Younger patients and those with better ECOG performance status had higher care scores than older and less active patients with pancreatic cancer (Appendix 2). ARIA+ category, area level socio-economic status, age, ECOG performance status, institutional pancreatic cancer case volume, and specialist first seen were all factors that significantly influenced the care score (Box 2; Appendix 3). After adjusting for these factors, the care scores for patients living in rural areas were 11% lower (95% CI, 8–13%) than for those living in major cities. The care scores for patients living in more disadvantaged areas were up to 8% lower (95% CI, 6–11%) than for patients living in the least disadvantaged areas. Care score estimates for patients presenting to a low pancreatic cancer case volume hospital (fewer than ten presentations per year) were 13% lower (95% CI, 11–15%) than for those presenting to hospitals with more than 30 presentations annually. They were higher for patients for whom a hepatobiliary surgeon was the first specialist seen; scores for patients initially seeing a general surgeon were 10% lower (95% CI, 8–13%) (Box 2).

To further investigate the association between ARIA+ category and care score, models were then also adjusted for the pancreatic cancer case volume of the first hospital and specialist seen. The differences in the adjusted mean scores for major cities and rural areas (5% lower for rural patients; 95% CI, 3–8%) and between least and most disadvantaged areas (6% lower for most disadvantaged patients; 95% CI, 3–8%) were lower in this model.

For patients who had been clinically staged with non-metastatic disease, the factors most strongly associated with lower care scores were being seen initially by a general rather than a hepatobiliary surgeon (17% lower; 95% CI, 13–21%), living in a rural area rather than a major city (11% lower; 95% CI, 8–15%), and being at least 80 years of age (v aged less than 60 years: 16% lower; 95% CI, 13–20%). For patients diagnosed with metastatic disease, being seen at a lower volume facility (15% lower; 95% CI, 12–17%) and having a poorer ECOG performance status (11% lower; 95% CI, 7–15%) were the factors most strongly associated with quality of care.

Individual items of care were also examined. Less than one-third of patients received some items: 31% were presented to multidisciplinary teams (MDTs), received psychosocial support (19%), participated in clinical trials (7%), or were first seen by a hepatobiliary surgeon (19%). Most eligible patients were offered resection or received a valid reason why they were not (98%), had a tissue diagnosis (80%), saw a medical oncologist (86%), and were referred to palliative care (82%) (Box 1). There were significant differences for patients according to their ARIA+ category and area level socio-economic status; for example, 32 patients living in rural areas (41%) were referred to a hepatobiliary surgeon, compared with 53% of patients (290 of 548) in metropolitan areas (Appendix 4, Appendix 5).

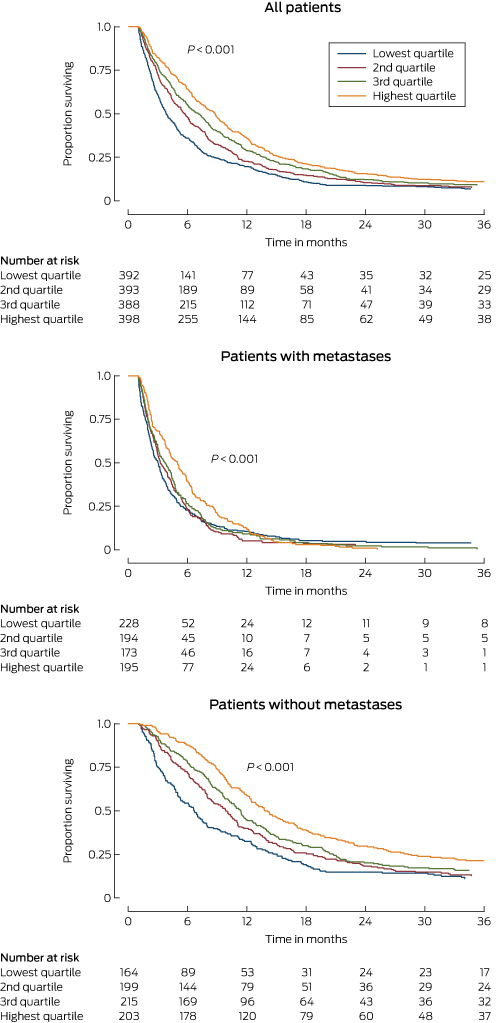

Patients with scores in the highest quartile of proportional care scores had an estimated median survival time of 8 months, double that for those with scores in the lowest quartile. Median survival time for patients with non-metastatic disease in the highest and lowest score quartiles was 14 and 7 months respectively; for those with metastatic disease, it was 5 and 3 months (Box 3).

After adjusting for age, ECOG performance status, comorbidities, and clinical stage of pancreatic disease, each 10 percentage point increase in proportional care score was associated with a statistically significant 6% reduction in the risk of dying (hazard ratio [HR], 0.94; 95% CI, 0.91–0.97; Box 4). The reduction was greater for patients who were diagnosed with non-metastatic disease (adjusted HR, 0.91; 95% CI, 0.87–0.95) than for those with metastatic disease (adjusted HR, 0.95; 95% CI, 0.91–0.99).

Individual care score items that were statistically significantly associated with survival included having a diagnostic tissue sample collected (HR, 0.66; 95% CI, 0.57–0.77), being offered adjuvant chemotherapy (HR, 0.43; 95% CI, 0.33–0.56), being referred to a hepatobiliary surgeon if potentially resectable (HR, 0.82; 95% CI, 0.69–0.96), being presented to an MDT (HR, 0.86; 95% CI, 0.77–0.96), being offered psychosocial support (HR, 1.24; 95% CI, 1.09–1.12), pancreatic enzyme replacement therapy (HR, 0.83; HR, 95% CI, 0.73–0.94), and, if diagnosed with metastatic disease, referral to palliative care (HR, 1.42; 95% CI, 1.17–1.74) (Appendix 6).

Discussion

We found that the quality of care for patients with pancreatic cancer varied according to their age, where they live, and the pancreatic cancer case volume of the hospital to which they first presented. We also found that higher quality of care was associated with improved survival. This association was strongest for patients clinically staged with non-metastatic pancreatic cancer, for whom there is more scope for treatment that can increase survival.

Earlier studies found that receiving surgery, chemotherapy and palliative care was influenced by the age, education, place of residence, ethnic background, and marital status of patients.5,7,15 By applying a composite measure of care that included a broad range of factors, we found that age and ECOG performance status influenced its overall quality. While this is unsurprising, it is important to recognise that age alone is not a barrier to high quality care. Our more worrying finding is that quality of care varied according to the geographic classification and the area level socio-economic status of the patient’s place of residence. This is at least partly explained by differences in access to specialists and care in high case volume centres, suggesting that interventions which ensure that all patients are managed by high volume teams could improve the quality of care.

Our analysis of individual care items found that the proportion of people receiving care from specialist teams, as recommended, was particularly small: fewer than one-third of patients had been referred to an MDT, only half of potentially resectable patients had been referred to a hepatobiliary surgeon, and referral to a clinical trial was only rarely considered, even though these factors have consistently been found to influence the quality of care.9,16,17 These aspects of care were particularly poorly delivered to patients living in more rural areas. Distance causes particular challenges in Australia,18–20 but they should not be insurmountable; it has been reported, for example, that a multi-level approach (such as telemedicine MDTs and formalising referral relationships between regional and metropolitan centres) can improve outcomes.21

Survival for patients with lower care scores was poorer, consistent with previous reports.22–24 This association was stronger for patients diagnosed with non-metastatic disease, for whom there is more scope for influencing survival by ensuring that staging is adequate, that surgery is undertaken in high case volume centres, and that patients have access to adjuvant chemotherapy. For patients with metastatic disease, a focus on quality-of-life indicators is arguably more important; this could be explored in further investigations of care quality.

Some care items were associated with a greater hazard of dying when the care was received, including statements that patients should be “offered psychosocial support”, that “patients with metastatic disease should be referred to palliative care”, and that “patients with technically resectable disease should be offered resection or a valid reason for no surgery”. Receiving psychosocial and palliative care is more likely as the expected survival time shortens, and this probably explains these findings (reverse causation). The care item regarding resection was classed as having been delivered if a valid reason for the resection not being offered had been recorded. This applied to 28% of patients eligible for resection; the reasons for not attempting surgery included older age, comorbidity, and poor ECOG performance status, each of which were associated with poor survival. When these three care items were all omitted from the care score, the risk of death was 2% lower for each 10 percentage point increase in care score (data not shown).

Our study was comprehensive, reasonably large, and population-based, and was also the first Australian investigation to assess the overall quality of care with a single score. Nevertheless, it had some limitations. Firstly, different weights for the care items may have been obtained if another mix of specialists had participated in the Delphi process. Secondly, the Delphi study highlighted the importance of communication between patients and clinicians. This factor cannot be adequately captured in a medical record review and could therefore not be incorporated into our score, but may have influenced decisions regarding care. Thirdly, some patients may have been incorrectly classified as having resectable tumours, which would have affected their eligibility for certain care items and thereby the delivery of appropriate care. Finally, although we controlled for age, ECOG performance status and comorbidities, we may not have completely accounted for confounding patient-related factors.

In conclusion, our population-based study provides evidence that the geographical location of their place of residence, among other factors, influences the quality of care received by Australian patients with pancreatic cancer, and that survival can be improved by delivering optimal care. Systems of care need to be implemented which ensure that equitable treatment is provided for all Australian patients with pancreatic cancer.

Box 1 –

Statements about care for patients with pancreatic cancer deemed to be most important in our Delphi process, patient eligibility criteria, and definition of care received

|

Care statement |

Weight* |

Eligible patients† |

Number eligible |

Number who received care‡ |

Care received |

||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||

|

All patients with potentially resectable disease should be referred to a hepatobiliary surgeon§ |

9.3 |

Non-metastatic |

781 |

401 (51%) |

Any referral or consultation with hepatobiliary surgeon¶ |

||||||||||

|

All patients with technically resectable disease should be offered resection or valid reason for not doing so |

9.2 |

Potentially resectable |

519 |

509 (98%) |

Surgery attempted or valid reason for not doing so |

||||||||||

|

Surgery should be performed by surgeons who perform more than five pancreatic resections per year |

9.0 |

Resection attempted |

366 |

158 (43%) |

Surgeon performed more than five resections per year |

||||||||||

|

Tumour resectability should be assessed by an MDT at a tertiary hospital |

9.0 |

Non-metastatic |

781 |

229 (29%) |

MDT prior to attempted surgery, or within 40 days of diagnosis if no surgery |

||||||||||

|

All patients should have a triple phase/pancreas protocol CT scan for staging |

8.9 |

All patients |

1571 |

674 (43%) |

Evidence of pancreas protocol CT |

||||||||||

|

Entry into a clinical trial should be considered for all patients |

8.8 |

All patients |

1571 |

103 (7%) |

Clinical trial discussed, considered, offered or participated in a trial |

||||||||||

|

Surgery should take place in tertiary institutions where more than 15 resections are performed annually** |

8.6 |

Resection attempted |

366 |

152 (42%) |

Attempted resection performed at hospital with more than 11 resections each year** |

||||||||||

|

Each patient should be assigned a care coordinator and an individualised treatment/clinical plan |

8.5 |

All patients |

1571 |

345 (22%) |

Evidence of a navigator, care plan or nursing referral |

||||||||||

|

Tissue diagnosis should be obtained where possible |

8.3 |

All patients |

1571 |

1251 (80%) |

Histology or cytology analysis completed |

||||||||||

|

All patients should be presented to an MDT |

8.3 |

All patients |

1571 |

494 (31%) |

Evidence of presentation to an MDT |

||||||||||

|

Biliary obstruction should routinely be managed endoscopically in non-resectable patients |

8.2 |

Non-resectable with biliary obstruction |

416 |

346 (83%) |

Evidence of endoscopic biliary stent, not bypass surgery |

||||||||||

|

All patients should be offered adjuvant therapy after surgery, assuming performance status is adequate |

8.1 |

Resection attempted |

366 |

244 (67%) |

Evidence of any adjuvant chemo- or radiation therapy |

||||||||||

|

All patients should be offered psychosocial support |

8.0 |

All patients |

1571 |

301 (19%) |

Evidence of referral to or consultation with psychological services |

||||||||||

|

Pancreatic enzyme replacement therapy should be considered for all patients |

7.9 |

All patients |

1571 |

345 (22%) |

Evidence of pancreatic enzyme replacement |

||||||||||

|

All patients should see a medical oncologist |

7.9 |

All patients |

1571 |

1353 (86%) |

Seen by a medical oncologist or valid reason why not |

||||||||||

|

A specialist hepatobiliary surgeon should be the initial/primary specialist unless the patient has obvious metastases |

7.3 |

Non-metastatic |

781 |

146 (19%) |

Hepatobiliary surgeon was the first specialist seen |

||||||||||

|

All patients should be referred to a dietitian soon after diagnosis |

7.3 |

All patients |

1571 |

1000 (64%) |

Evidence of referral to or consultation with dietitian |

||||||||||

|

Patients with confirmed metastatic disease should be referred to palliative care |

6.0 |

Metastatic |

790 |

646 (82%) |

Any evidence of palliative care consultation or referral¶ |

||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||

|

CT = computerized tomography; MDT = multidisciplinary team meeting. * Final mean average score of importance from Delphi process. † Patients eligible for care according to classification by clinical staging. ‡ Number and percentage of eligible patients who received the item of care. § Hepatobiliary surgeon: defined as a surgeon who had undergone recognised specialist hepatobiliary surgery training or who was recognised by peers as an experienced hepatobiliary surgeon. ¶ Includes all inpatient records and consultations. ** Only three hospitals from the patterns of care study performed 15 resections each year; this high volume classification was therefore amended, on the basis of Australian data and literature reports, to hospitals where 11 or more resections were performed each year. |

|||||||||||||||

Box 2 –

Associations between patient, tumour and health service-related characteristics and proportional care scores for all patients, and for patients with or without evidence of metastases at clinical staging

|

|

Adjusted β coefficient (95% confidence interval)* |

||||||||||||||

|

All patients |

Patients without metastases |

Patients with metastases |

|||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||

|

Number of patients |

1571 |

781 |

790 |

||||||||||||

|

Age group |

|

|

|

||||||||||||

|

< 60 years |

Reference |

Reference |

Reference |

||||||||||||

|

60–69 years |

0.01 (−0.01 to 0.03) |

0.01 (−0.02 to 0.04) |

0.00 (−0.03 to 0.04) |

||||||||||||

|

70–79 years |

−0.05 (−0.08 to −0.03) |

−0.05 (−0.08 to −0.02) |

−0.06 (−0.09 to −0.03) |

||||||||||||

|

≥ 80 years |

−0.13 (−0.15 to −0.10) |

−0.16 (−0.20 to −0.13) |

−0.10 (−0.13 to 0.06) |

||||||||||||

|

P (overall; trend) |

< 0.001; < 0.001 |

< 0.001; < 0.001 |

< 0.001; < 0.001 |

||||||||||||

|

Sex |

|

|

|

||||||||||||

|

Women |

Reference |

Reference |

Reference |

||||||||||||

|

Men |

−0.01 (−0.02 to 0.01) |

0.01 (−0.01 to 0.03) |

−0.03 (−0.05 to −0.00) |

||||||||||||

|

P (overall) |

0.34 |

0.40 |

0.03 |

||||||||||||

|

Charlson comorbidity score |

|

|

|

||||||||||||

|

0 |

Reference |

Reference |

Reference |

||||||||||||

|

1 |

−0.01 (−0.03 to 0.01) |

−0.00 (−0.03 to 0.02) |

−0.01 (−0.03 to 0.02) |

||||||||||||

|

2 |

−0.01 (−0.03 to 0.01) |

−0.01 (−0.04 to 0.02) |

−0.01 (−0.04 to 0.02) |

||||||||||||

|

P (overall; trend) |

0.64; 0.38 |

0.88; 0.63 |

0.89; 0.66 |

||||||||||||

|

ECOG performance status |

|

|

|

||||||||||||

|

0 |

Reference |

Reference |

Reference |

||||||||||||

|

1 |

−0.01 (−0.03 to 0.01) |

−0.01 (−0.04 to 0.02) |

−0.01 (−0.04 to 0.02) |

||||||||||||

|

≥ 2 |

−0.06 (−0.08 to −0.03) |

−0.06 (−0.09 to −0.03) |

−0.05 (−0.08 to −0.02) |

||||||||||||

|

Not stated |

−0.09 (−0.12 to −0.06) |

−0.07 (−0.11 to −0.03) |

−0.11 (−0.15 to −0.07) |

||||||||||||

|

P (overall; trend) |

< 0.001; < 0.001 |

< 0.001; < 0.001 |

< 0.001; < 0.001 |

||||||||||||

|

Residence (ARIA+ classification) |

|

|

|

||||||||||||

|

Major city |

Reference |

Reference |

Reference |

||||||||||||

|

Inner regional |

−0.06 (−0.08 to −0.04) |

−0.03 (−0.06 to −0.00) |

−0.08 (−0.11 to −0.05) |

||||||||||||

|

Rural† |

−0.11 (−0.13 to −0.08) |

−0.11 (−0.15 to −0.08) |

−0.09 (−0.13 to −0.06) |

||||||||||||

|

P (overall; trend) |

< 0.001; < 0.001 |

< 0.001; < 0.001 |

< 0.001; < 0.001 |

||||||||||||

|

Socio-economic status (quintiles) |

|

|

|

||||||||||||

|

1 (least disadvantaged) |

Reference |

Reference |

Reference |

||||||||||||

|

2 |

−0.03 (−0.06 to −0.01) |

−0.04 (−0.07 to −0.00) |

−0.03 (−0.07 to 0.01) |

||||||||||||

|

3 |

−0.07 (−0.10 to −0.04) |

−0.08 (−0.12 to −0.05) |

−0.06 (−0.10 to −0.02) |

||||||||||||

|

4 |

−0.08 (−0.11 to −0.05) |

−0.08 (−0.12 to −0.05) |

−0.08 (−0.12 to −0.04) |

||||||||||||

|

5 (most disadvantaged) |

−0.08 (−0.11 to −0.06) |

−0.07 (−0.10 to −0.03) |

−0.10 (−0.13 to −0.06) |

||||||||||||

|

P (overall; trend) |

< 0.001; < 0.001 |

< 0.001; < 0.001 |

< 0.001; < 0.001 |

||||||||||||

|

Clinical stage of disease |

|

|

|

||||||||||||

|

Confined to pancreas |

Reference |

NA |

NA |

||||||||||||

|

Locally advanced |

−0.02 (−0.04 to 0.01) |

||||||||||||||

|

Metastatic |

−0.02 (−0.04 to 0.00) |

||||||||||||||

|

P (overall; trend) |

0.26; 0.14 |

||||||||||||||

|

Pancreatic cancer case volume of first facility seen |

|

|

|

||||||||||||

|

> 30 per year |

Reference |

Reference |

Reference |

||||||||||||

|

10–29 per year |

−0.06 (−0.08 to −0.04) |

−0.07 (−0.10 to −0.05) |

−0.04 (−0.07 to −0.02) |

||||||||||||

|

< 10 per year |

−0.13 (−0.15 to −0.11) |

−0.10 (−0.13 to −0.07) |

−0.15 (−0.17 to −0.12) |

||||||||||||

|

P (overall; trend) |

< 0.001; < 0.001 |

< 0.001; < 0.001 |

< 0.001; < 0.001 |

||||||||||||

|

First specialist seen |

|

|

|

||||||||||||

|

Hepatobiliary surgeon |

Reference |

Reference |

Reference |

||||||||||||

|

Gastroenterologist |

−0.09 (−0.11 to −0.06) |

−0.12 (−0.15 to −0.09) |

−0.03 (−0.07 to 0.01) |

||||||||||||

|

General surgeon |

−0.10 (−0.13 to −0.08) |

−0.13 (−0.16 to −0.10) |

−0.05 (−0.09 to −0.01) |

||||||||||||

|

Other |

−0.14 (−0.16 to −0.11) |

−0.17 (−0.21 to −0.13) |

−0.10 (−0.14 to −0.06) |

||||||||||||

|

P (overall) |

< 0.001 |

< 0.001 |

< 0.001 |

||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||

|

ECOG = Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group; NA = not applicable. * Adjusted for age group at diagnosis (< 60, 60–69, 70–79, ≥ 80 years), ECOG performance status (0, 1, ≥ 2, not stated), and Charlson comorbidity index score (0, 1, ≥ 2). † Includes patients in outer regional, remote and very remote areas. |

|||||||||||||||

Box 3 –

Kaplan–Meier survival curves for all patients, patients with non-metastatic disease and patients with metastatic disease on clinical staging, by proportional care score (quartiles)

* Log-rank test of equality of survivor functions across proportional care score quartiles.

Box 4 –

Association between total care score and survival according to stage of pancreatic cancer at diagnosis

|

|

Number of patients |

Hazard ratio (95% CI)* |

|||||||||||||

|

Unadjusted |

P |

Adjusted† |

P |

||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||

|

All patients |

1571 |

0.90 (0.87–0.93) |

< 0.001 |

0.94 (0.91–0.97) |

< 0.001 |

||||||||||

|

Non-metastatic disease |

781 |

0.87 (0.83–0.91) |

< 0.001 |

0.91 (0.87–0.95) |

< 0.001 |

||||||||||

|

Metastatic disease |

790 |

0.95 (0.91–0.98) |

0.006 |

0.95 (0.91–0.99) |

0.013 |

||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||

|

* Reduction in the risk of dying associated with a 10 percentage point increase in care score. † Adjusted for age group, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status, Charlson comorbidity score, and clinical stage. |

|||||||||||||||

more_vert

more_vert