During 2015, reports of problems arising from the use of the crystalline form of methamphetamine known as “ice” or “crystal” have attracted increased media, community and policy attention in Australia.1,2 There were substantially more seizures of methamphetamine at the border during this time,3 and the media reported these developments in terms of an “epidemic” of methamphetamine use. Researchers and law enforcement officials have disagreed about whether its use has increased; household survey data on the prevalence of use in the past year and surveys of drug users have been interpreted as showing that methamphetamine use has, in fact, been stable.4,5

We need credible estimates of the number of regular and dependent methamphetamine users in Australia. It is these patterns of use that are of greatest concern from both the public health and public order points of view. These groups include the users most likely to experience harms such as psychoses and serious medical problems that require hospital treatment. People who use illicit drugs heavily are not well captured in household surveys, in which less frequent use is typically reported; in the most recent national household survey, for instance, 48% of those who had used methamphetamine in the past year in Australia had used it only once.6

Our study assessed the current extent of problematic methamphetamine use in Australia by estimating the numbers of regular and dependent methamphetamine users in Australia. We used indirect prevalence estimation methods that have been widely applied in illicit drug epidemiology to estimate the size of more hidden and stigmatised groups of illicit drug users.7–10 Specifically, we aimed to generate:

-

annual estimates of the numbers of users and of population rates of regular and dependent methamphetamine use for the period 2002–2014; and

-

age-specific estimates of the numbers of users and of population rates of regular methamphetamine use and methamphetamine dependence over the same period.

Methods

We estimated the sizes of two populations of methamphetamine users in Australia:

-

the number of regular users: those who used the drug at least once a month during the past year;

-

the number of dependent methamphetamine users: those who have impaired control of their use, and who continue to use the drug despite the health and other adverse consequences that they might be experiencing (as defined in the World Health Organization’s International Classification of Diseases [ICD]).

It is important to note that these two populations of methamphetamine consumers overlap (with dependent users being a subgroup of those who use the drug regularly). Estimates of the sizes of these two populations of users are therefore not additive (see the section on multipliers below).

We applied indirect methods of estimation.7,8 These methods draw on different sources of data to indirectly estimate the total number of drug users.7 One indirect approach is the multiplier method; for example, multiplying the number of people who received drug treatment during a particular year (an indicator or benchmark for use) by an estimate of the proportion of dependent drug users who received treatment during the year (the multiplier) to produce an estimate of the total size of the dependent drug-using population. A worked example of an estimate generated using the multiplier method is presented in Box 1. These methods have been widely applied in research into illicit drug use to estimate relatively hidden or stigmatised patterns of illicit drug use. Their strengths and limitations have been discussed at length elsewhere.7,8

Following an extensive investigation of the most robust multipliers that could be used to estimate the number of regular and dependent methamphetamine users in Australia in 2004 (see Appendix), multiple estimates were made according to the approach described by McKetin and colleagues.11

Data sources

A number of data types were explored as potential sources of benchmark data: hospital admissions data, drug dependence treatment data, arrest data, emergency department admissions data, and ambulance service data. Of these, amphetamine dependence treatment episodes and amphetamine-related hospital separations were the only data that enabled methamphetamine-related cases to be clearly identified, and were therefore the sole data we used to generate estimates. The same conclusion was drawn in a previous Australian investigation.11 Further details on the selection of data sources are presented in the online Appendix. Analysis of benchmark data was restricted to incidents in people aged 15–54 years, the same age range covered by the data sources used to calculate the multipliers.

Treatment episodes for amphetamine use

We obtained data on publicly and non-government-funded specialised closed amphetamine treatment episodes, which are compiled by the National Minimum Data Set for Alcohol and Other Drug Treatment Services (NMDS-AODTS). We obtained data on episodes in which the main drug of concern was listed as “amphetamines” (which includes amphetamine and methamphetamine).

This dataset does not include treatment episodes undertaken in halfway houses and sobering-up shelters, correctional institutions, health promotion services (eg, needle and syringe exchange programs), acute care and psychiatric hospitals that only treat admitted patients, or private treatment agencies that do not receive government funding. Further details on the nature of the data included in the NMDS-AODTS are reported elsewhere.12

Hospital separations for amphetamine use

Hospital separations included those for a primary stimulant-related diagnosis. This included the diagnoses of “Mental and behavioural disorders due to use of other stimulants, including caffeine” (ICD-10 codes, F15.X) and “Poisoning by psychotropic drugs, not elsewhere classified — Psychostimulants with potential for use disorder” (ICD-10 code, T43.6).

Multipliers

Ideally we would have used multipliers compiled on an annual basis, but major limitations in each of the data sources we investigated for deriving multipliers prevented this, as discussed in the Appendix. Our multipliers were therefore derived from a survey of 310 regular methamphetamine users recruited from across Sydney during 2002–03 who used methamphetamine at least once a month during the 6 months prior to the interview.11 They were recruited both through advertisements and through outpatient community health services to avoid oversampling methamphetamine users in treatment or in hospital. Multipliers were also adjusted for the number of hospital and treatment events per person during the past year (that is, the annual rate of events), and were restricted to those events that would have been recorded in the benchmark data sources (Box 2).

An additional set of multipliers was calculated for the subset of 166 participants who were both regularly using and dependent on methamphetamine during the past year. Dependence was defined as having a score of 4 or greater on the Severity of Dependence Scale, which corresponds to a Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (DSM-III-R) diagnosis of severe methamphetamine dependence.13 Most dependent methamphetamine users injected the drug (76%), and were more likely to have a history of heroin use than their non-dependent counterparts (72% v 58%: odds ratio [OR], 1.9; P = 0.007).

Analyses

Multipliers were applied to the benchmark data for each financial year for which data were available (2002–03 to 2013–14). As we used two sources of benchmark data (treatment episodes and hospital separations), we obtained two estimates of the numbers of regular and dependent methamphetamine users for each financial year. We pooled these two estimates using fixed effects meta-analysis methods in Stata 13 (StataCorp).14 As the confidence intervals were skewed, we log-transformed the estimates and their confidence intervals (CIs) for the meta-analysis, and then back-transformed the estimates to obtain summary results. Finally, we generated rates per 100 population from the Australian Bureau of Statistics estimates of the resident population on 30 June for each year.

Ethics

Ethics approval for access to hospital and treatment data to generate these estimates was obtained under the National Illicit Drug Indicators Project (UNSW Human Research Ethics Committee; reference, HC13081).

Results

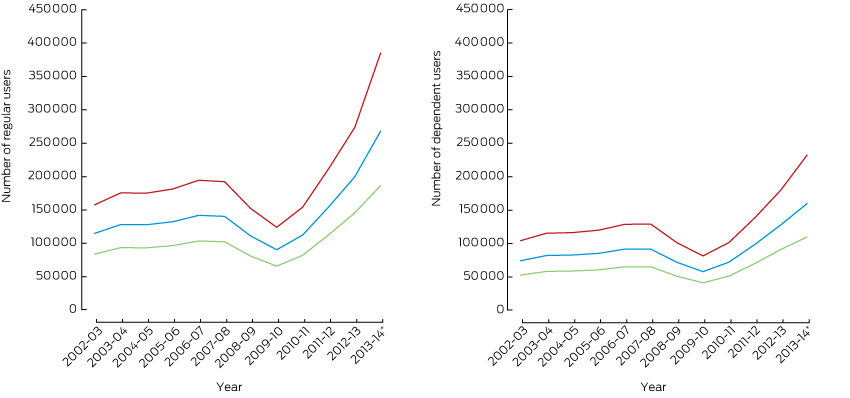

The pooled estimates of the numbers of regular and dependent methamphetamine users varied during the study period, but were all higher in the most recent years. It was estimated that in 2013–14 there were 268 000 regular (at least monthly) methamphetamine users (95% CI, 187 000–385 000), and 160 000 dependent users (95% CI, 110 000–232 000) aged 15–54 years (Box 3). This equates to population rates of 2.09% (95% CI, 1.45–3.00%) for regular and 1.24% (95% CI, 0.85–1.81%) for dependent use (Appendix, Figure A1; Box 4). The estimated rate in 2013–14 was higher than in 2009–10, when the rate was 0.74%, and also higher than the previous peak, 1.22% in 2006–07. The Appendix presents the estimates based on the individual data sources.

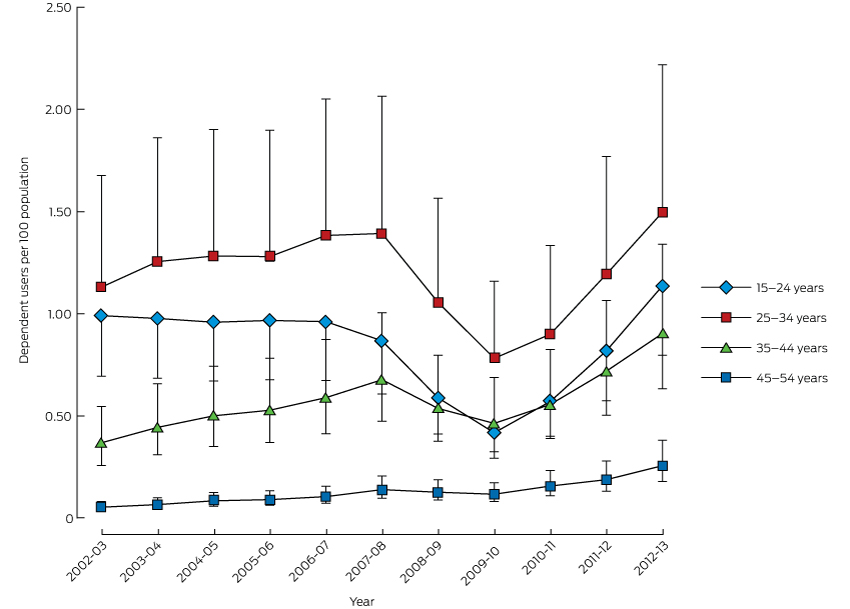

Estimates of the rates of regular and dependent use varied with age and over time (Box 5). The highest rates of use were consistently among those aged 25–34 years. In 2012–13, the estimated rate of methamphetamine dependence in this age group was 1.50% (95% CI, 1.05–2.22%). It is also important to note the recent increase in estimated dependent use among those aged 15–24 years; in 2012–13 the rate was estimated to be 1.14% (95% CI, 0.80–1.69%).

Discussion

There was a clear increase in our estimates of the numbers of dependent and regular methamphetamine users in Australia since 2010, with the largest increases in the 25–34 and 15–24-year-old age groups.

Patterns of stimulant use often show a rapid uptake among new users who initially report extremely rewarding effects that they advertise to their peers, thereby recruiting further new users. There is often a swift development of problem use among heavy users, whose doses escalate as tolerance develops; these problems typically include psychoses and dependence, and arrests for drug possession and supply. The emergence of these problems produces a rapid decline in new recruits as the high visibility of these harms becomes apparent to non-using peers.15

Recent surveys suggest that this phenomenon has occurred in Australia. Findings from the internet-administered Global Drug Survey (http://www.globaldrugsurvey.com) suggest that methamphetamine may have acquired a negative reputation among older drug users, who report lower use; the same may be true among regular ecstasy users surveyed in Australian capital cities.16 A recent analysis of Australian household surveys of drug use over the past two decades further supports the view that methamphetamine use has become increasingly stigmatised, with fewer people admitting to having used the drug, suggesting that these surveys underestimate an increasingly stigmatised form of substance use.17

Rapid uptake of methamphetamine use may still be occurring outside the largest cities, especially in regional centres where young people without prior experience of methamphetamine may be exposed to it. The available data, together with findings reported in this article, suggest a sharp increase in problematic methamphetamine use among particular subgroups (particularly young people) in Australia. These problem users require targeted and specific policy and treatment responses.

Clinical implications

There is a need for both more health services and better engagement with and retention of clients in treatment services. There are no effective pharmacotherapy options for the treatment of methamphetamine dependence.18 Best practice in treatment involves intensive application of structured psychological and behavioural therapies, such as cognitive behavioural therapies and contingency management,19 but this is not well translated into practice.20 For more entrenched dependent users, long-stay residential treatment options can produce positive short term outcomes (compared with no treatment),21 although high relapse rates after one to three years indicate that methamphetamine dependence can become chronic and relapsing.21 Ongoing engagement in treatment and improved access to evidence-based treatment options are essential for improving the health of dependent methamphetamine users.

Limitations

The use of multipliers from 2002–03 may be questioned because of changes in the type of drug used and the types of users, namely:

-

large increases in the purity of crystal methamphetamine;

-

changes in the route of administration (smoking has become the predominant route used by newer users, rather than injecting, the primary route in 2002–03); and

-

recruitment of a new cohort of younger users whose patterns of use (primarily smoking) differs from that of older injecting drug users and regular stimulant users.

These changes may have increased the rate of dependence among users, and thus increased the proportion of methamphetamine users who become regular or dependent users. Research suggests that crystal methamphetamine users are nearly twice as likely to develop dependence as those using other forms of methamphetamine.22 The same seems to be true of those who smoke rather than snort or swallow the drug.23

What effects might these changes have on the estimated number of users? For example, increased smoking of crystal methamphetamine during the past decade among people with no history of regular or problematic drug use may have increased the number of regular or dependent smokers of crystal methamphetamine who seek treatment. If so, our treatment-based multiplier, which was based on a sample of methamphetamine users who had high rates of injecting drug use and a long history of polydrug use, may overestimate the true population multiplier.

On the other hand, some treatment services report that crystal methamphetamine smokers are less likely to undergo treatment (unpublished data from the Methamphetamine Treatment Evaluation Study21). More research is needed to examine this question. If the proportion of methamphetamine users who smoke crystal methamphetamine is increasing, then our multiplier for treatment access, derived from a sample of people who mostly inject methamphetamine, may be too low. If this is the case, we have underestimated the number of problem methamphetamine users.

It might also be argued that multipliers based on surveys of methamphetamine users in Sydney are not representative for all users in Australia. For example, treatment is more available in major capital cities than in regional or remote areas, or in a smaller capital city. Our estimates of the proportion of users who are treated would then be higher in Sydney than elsewhere, making the multiplier smaller than it should be for other areas. If, for example, 10% of users in Sydney received treatment in the past year, but only 5% did so in rural centres, the Sydney multiplier would be half what it would have been in regional areas (10 in Sydney, 20 in other areas). This would mean that our estimates are conservative estimates of the national population of regular or dependent methamphetamine users.

Finally, it is important to note that there were no changes in the methods or quality of data collection during 2009–10; the reduced numbers of treatment and hospital episodes were consistent with indicators of availability and harm related to amphetamines in that period.24

Conclusions

Our estimates suggest that there have been substantial increases over the past 5 years in the numbers of regular and dependent methamphetamine users in Australia. The estimated levels of regular and dependent methamphetamine use during 2012–13 are the highest for the period examined. These increases have been most marked among young adults aged 15–34 years. The increased number of problem methamphetamine users indicates a need to expand services to redress the health problems associated with regular methamphetamine use.

Box 1 –

Hypothetical example of the estimation of the number of dependent amphetamine users based on the number of treatment episodes for amphetamine dependence

|

|

|||||||||||||||

|

Benchmark data: the number of episodes across Australia in a given year for the treatment of amphetamine dependence. |

|||||||||||||||

|

Multiplier: the inverse of the proportion of users who are amphetamine-dependent and who received treatment in a given year. |

|||||||||||||||

|

In this hypothetical example, data suggest that 20 000 Australians received treatment for amphetamine dependence in a given year. Surveys of dependent amphetamine users indicate that 10% received treatment in this year, giving a multiplier of 10. |

|||||||||||||||

|

The estimated total number of dependent amphetamine users is the product of the benchmark data and the multiplier; ie, 20 000 × 10 = 200 000 dependent users. |

|||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||

Box 2 –

The rate of benchmark events per 100 persons per year, and multipliers for regular and dependent methamphetamine use

|

Rate (95% CI) |

Multiplier (95% CI) |

||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||

|

Methamphetamine treatment |

|||||||||||||||

|

Regular users |

10.8 (7.4–15.2) |

9.3 (6.6–13.6) |

|||||||||||||

|

Dependent users |

18.1 (12.2–25.8) |

5.5 (3.9–8.2) |

|||||||||||||

|

Methamphetamine-related hospitalisation |

|||||||||||||||

|

Regular users |

3.7 (1.9–6.6) |

26.9 (15.0–53.9) |

|||||||||||||

|

Dependent users |

4.2 (1.7–8.7) |

23.7 (11.5–59.0) |

|||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||

|

Derived from the study by McKetin and colleagues11 that measured the rate of key events in the previous year among regular and dependent methamphetamine users. |

|||||||||||||||

Box 3 –

Pooled estimates of the numbers of regular and dependent methamphetamine users aged 15–54 years in Australia, 2002–2014 (with 95% confidence intervals)*

* The estimates for 2013–14 are based on indirect estimates generated from treatment data alone. Please see the Appendix for the estimates based on individual data sources. Note that the estimates of the number of people using methamphetamine regularly and the number of people dependent upon methamphetamine are not additive, as there is substantial overlap between the two populations (dependent users are a subset of the regular use group).

Box 4 –

Pooled estimates of the numbers of regular and dependent users of methamphetamine per 100 persons aged 15–54 years in Australia, 2002–2014

|

Regular users |

Dependent users |

||||||||||||||

|

Rate |

95% CI |

Rate |

95% CI |

||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||

|

2002–03 |

1.03 |

0.75–1.41 |

0.66 |

0.47–0.93 |

|||||||||||

|

2003–04 |

1.14 |

0.83–1.56 |

0.73 |

0.52–1.02 |

|||||||||||

|

2004–05 |

1.12 |

0.82–1.54 |

0.73 |

0.52–1.02 |

|||||||||||

|

2005–06 |

1.15 |

0.84–1.58 |

0.74 |

0.53–1.05 |

|||||||||||

|

2006–07 |

1.22 |

0.89–1.67 |

0.79 |

0.56–1.11 |

|||||||||||

|

2007–08 |

1.19 |

0.86–1.62 |

0.78 |

0.55–1.09 |

|||||||||||

|

2008–09 |

0.92 |

0.67–1.26 |

0.60 |

0.42–0.84 |

|||||||||||

|

2009–10 |

0.74 |

0.54–1.01 |

0.47 |

0.34–0.67 |

|||||||||||

|

2010–11 |

0.91 |

0.66–1.24 |

0.58 |

0.41–0.82 |

|||||||||||

|

2011–12 |

1.23 |

0.90–1.69 |

0.79 |

0.56–1.11 |

|||||||||||

|

2012–13 |

1.57 |

1.15–2.15 |

1.01 |

0.72–1.42 |

|||||||||||

|

2013–14* |

2.09 |

1.45–3.00 |

1.24 |

0.85–1.81 |

|||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||

|

* The estimates for 2013–14 are based on indirect estimates generated from treatment data alone. Note that the estimates of the number of people using methamphetamine regularly and the number of people dependent upon methamphetamine are not additive, as there is substantial overlap between the two populations. |

|||||||||||||||

more_vert

more_vert