One of the greatest opportunities in Australian public health is to reduce the mortality and morbidity caused by mental illness. In contrast to cancer and cardiovascular disease, there have been no improvements in rates of death or disability from mental illness in recent decades. Indeed, rates of suicide have increased,1 and mental illness is the largest and fasting growing source of disability.2 Prevention, early diagnosis and sustained access to evidence-based treatment have underpinned health gains in other diseases, yet these are poorly provided by a mental health system that is characterised by a self-perpetuating focus on acute care and welfare payments.3

With mental illness projected to have the greatest impact on global economic output of all non-communicable diseases,4 there is an economic imperative to replicate what has been accomplished for other diseases. The mental health reforms announced by the Prime Minister and the Minister for Health on 26 November 2015 outlined new directions,5 two of which, in particular, are highly congruent to achieving this goal. However, the reform package is constrained by a focus on cost containment and will need further strengthening if it is to be successful.

The first welcome aim of reform is to shift the focus of mental health care towards early intervention. The National Mental Health Commission highlighted the enormous avertable personal, social and economic burden imposed by underprovision of prevention and early intervention in mental health.3 It is therefore welcome that the government has endorsed this aim,6 but notable that it has not committed the funding to make it happen. This crucial plank of reform may remain more rhetoric than reality. For example, acting on the advice of its Mental Health Expert Reference Group,7 the government announced a measure to develop much-needed new responses to young people with serious, non-psychotic mental illnesses. This is to be financed from funds that are already fully committed to an evidence-based, cost-effective model of early intervention for young people with a first episode of psychosis.8–12 Spreading already modest resources a mile wide and an inch deep would be an unpromising financing model for such a major reform objective. It would be safer and more logical to pilot a small number of novel approaches to young people with serious non-psychotic mental illness and to then provide new investment for those approaches that have most promise in terms of cost-effectiveness.

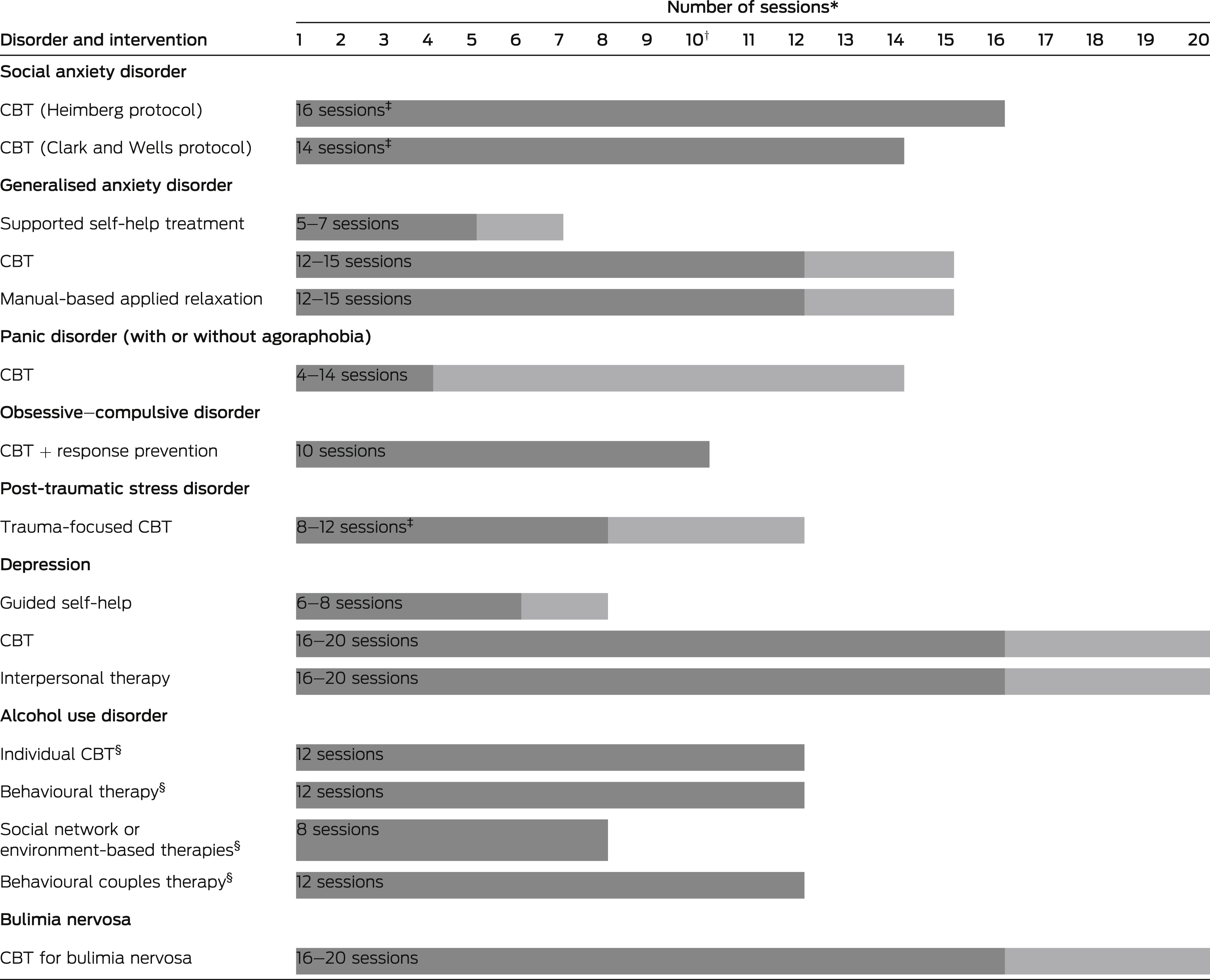

The second notable aim of reform is to move mental health services more towards providing stepped and person-centred care. This means supports must be targeted and weighted (right care, right intensity, right time) and more holistic. Achieving the goal of better targeting and weighting of support will depend on the government’s preparedness to also finance more intensive interventions, not just divert people with milder illnesses to lower intensity interventions. More holistic care may help overcome the excess burden of chronic physical illness that contributes to a median of 10 years of life lost for people with mental illness.13

The current funding constraints within which direct mental health care is provided mean that treatment, especially expert, specialised care, is heavily rationed and overly restricted to late presentations, with a duration frequently insufficient for remission and recovery. Of Australian adults with depression and anxiety, 16% receive only “minimally adequate treatment”,14 and the situation for those with psychotic illnesses reflects similar poor access to and variable quality of care.15 Unless something changes, the problem may get even worse, as federal support for state hospitals is set to reduce and state mental health services within these structures are already soft targets for hospital administrators.

Although largely neglecting the financing issue, the government has outlined potentially important actions at national and regional levels. National actions will include two national initiatives brought about by consolidating several school mental health programs that support promotion and prevention activity, and an array of digital mental health platforms. Flagged future national actions include Medicare reforms, the details of which are yet to be announced, and coordination of cross-departmental and intergovernmental activity. In a move away from centralised planning and contracting, primary health networks (PHNs) will now undertake local needs assessment and mapping, use pooled flexible funds to plan and commission a range of service responses for their regions, and work in partnership with local health networks to better integrate these services with state-funded mental health care.

These national and regional strategies to achieve earlier intervention and better targeted, stepped and more holistic care are consistent with the Commission’s recommendations3 and the advice of the government’s Mental Health Expert Reference Group,7 and have been cautiously welcomed by much of the mental health sector, which has been destabilised by chronic uncertainty.

In addition to more adequate funding, a key success factor for these reforms will be whether the PHN model of commissioning the mental health services needed in each local area functions well — and equally so in all regions. International experience suggests that devolving commissioning is not a magic bullet to improve health outcomes, that it creates predictable risks and that the impact of such measures depends on a range of supporting policy levers and environmental factors.16

Appropriate national structures, supports and oversight will be required to ensure PHNs can tailor programs to local circumstances, while maintaining fidelity to evidence-based practice and models of care. The virtue of regional planning flexibility cannot overshadow the need to invest in programs that work. Any new investment, and the repurposing of existing resources, must be channelled through commissioning of evidence-based interventions and proven models of care. It is at present unclear how this will be assured. It is essential that all major aspects of program innovation are appropriately trialled and evaluated before being codified in frameworks and guidelines that shape the development of services throughout all PHNs. International commissioning guidelines suggest that PHNs may be more likely to progress reform goals if they commission integrated, accessible, effective and holistic service platforms17 and appropriately engage consumers and carers in measurement and evaluation processes.18

Much of the funding allocated to the PHNs is focused on youth and early intervention. For young people, integrated, holistic, multicomponent primary care platforms achieve better results than do standard primary care platforms.19 The headspace platform3 will be central to how PHNs progress the reform aims of early intervention and stepped, holistic care, consistent with the Commission’s recommendation that this platform continue to be funded as a fundamental pillar of the youth mental health service system.3 As with other programs devolved to PHNs, there remains a need for strong national functions in areas such as data collection, evidence dissemination, model fidelity and workforce development. In the case of headspace, the Commission recommended these should be unified under a single national youth mental health umbrella.3

Other areas of national responsibility in the reform process, such as the digital mental health and Medicare reform agendas, also require an evidence-based and evidence-generating approach. Particular care is required in progressing the government’s plan to promote use of low-intensity and self-help strategies for people with milder forms of mental illness and to encourage general practitioners to be more sparing in referral of patients to face-to-face psychological services. Implicit in this plan is an assumption that many of the people currently accessing mental health care through primary care and the Better Access initiative could be more cost-effectively managed by e-health intervention strategies. This may well be true, at least in part, and the Better Access initiative represents a tempting target for funding cuts as it is seen as large, and is expanding. However, as an early step in the universal care pathway, a threshold of proof of safety and cost-effectiveness should be met before access to a GP and allied health professional is further constrained. E-health can be an excellent complement to all steps in the care pathway, not only the first, and it would be safer to offer it initially as a choice, rather than as a triage strategy or barrier.

The government has begun to acknowledge that we must do much better for the “missing middle” group of patients — those people with complex disorders who need to access the expert care that they are unlikely to ever receive from state-funded public mental health services.6 Care for this group should involve a step up in expertise from the initial GP and allied health professional, and ideally should involve a team approach, with input from a psychiatrist. In the case of non-response to this first step, more of the same may not be what is required for many people with complex and persistent disorders. This should be a federal responsibility, and a new model of care needs to be designed and tested in a defined subset of regions before any sweeping changes are made.

The other major group requiring consideration is older adults with persistent and disabling illnesses, particularly schizophrenia. Traditionally, being the target group for the asylums of old, they have been the major adult group eligible for state public mental health services. Yet, even they are underserved and have insecure access to care and sufficient duration of treatment, and outcomes — both physical and mental — remain well short of what is possible.15 This shortfall in care was the motivation behind the federal Partners in Recovery initiative (http://www.pirinitiative.com.au), which was formulated in 2011. This initiative, while popular, lacked a real evidence base or “road testing”, and the variability in the models of care that resulted conversely underlines the value of national templates that are based on best-available evidence and are properly tested before being scaled up. Federal funding to fill the service gaps for these patients would be better focused on more practical needs, such as family support, housing and specialised employment programs — all highly evidence-based but inadequately funded. Of great concern is that only a small proportion of these patients (estimated at about 10%) will be able to access the National Disability Insurance Scheme,20 yet it is feared that mental health funding may be lost in the process. The irony is that mental illness, by far the largest source of disability and for so long the poor cousin of the health system, is being forced into the same position within the new disability system. This must be dealt with as a matter of priority. The states should also be required to care much more adequately for their traditional core patient population.

Finally, there is an important role for new research funding programs that include, but are additional to, the National Health and Medical Research Council, and which are more directly tied to specific reform objectives. Potential reforms to Medicare Benefits Schedule items, such as incentives for GPs to provide longer consultations and for psychiatrists in private practice to integrate much better with primary care and other disciplines, as well as new and alternative uses of digital mental health strategies and systematic expansion of vocational recovery models, are areas that would benefit from such targeted funding schemes. The Medical Research Future Fund looms as an appropriate vehicle for funding some of this activity.

Australians now have a greatly increased awareness and understanding of the scale and impact of mental illness on their lives and society. The challenge is to transform this into targeted investment so that access, quality and outcomes in mental health care match those seen in physical health care.

more_vert

more_vert