This is a republished version of an article previously published in MJA Open

The social, economic and personal burdens caused by depression are substantial1 and well documented.2 Nonetheless, shortcomings in treatment of depression have been identified in both primary and specialised care, with respect to diagnosis, management and patient adherence.

Health professionals, including general practitioners, may be confused about diagnosis and management when clear definitions and acceptable taxonomy cannot be found. In the literature, terms including “difficult-to-treat depression”, “treatment-resistant depression”, “treatment-refractory depression”, “treatment-resistant major depressive disorder” and “major depressive disorder” are often used interchangeably,3–5 resulting in considerable confusion. Further problems arise because of a mismatch between current classification systems, such as the Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, fourth edition (DSM-IV) or the International Classification of Diseases, and the possible clinical phenotypes of mental disorders, particularly as they present in primary care.6 It has also been suggested that meaningful subtypes of depression might have different treatment outcomes, raising another clinical imperative for accurate diagnosis.

Against this background, we aimed to explore GPs’ understanding of the definitions of and management guidelines for difficult-to-treat depression (DTTD), and their experiences of diagnosing and managing patients with DTTD.

During 2011, a convenience sample of GPs from inner Melbourne, outer Melbourne and rural Victoria was recruited through Monash University networks using an email invitation, followed by telephone contact.7,8

A semi-structured interview schedule comprising five topics was developed from the literature to address the study aims.7,8 Topics explored were: (1) understanding of DTTD; (2) understanding of other terms used to describe DTTD; (3) experiences of diagnosing DTTD; (4) experiences of managing DTTD; and (5) management options.

A 90-minute face-to-face focus group was conducted with participants from inner Melbourne. Participants from outer Melbourne and rural Victoria each had a telephone interview of 15–30 minutes’ duration. The focus group and interviews were audiotaped and transcribed verbatim. Data were collected in the latter half of 2011 by one of us (K J).

Data were analysed manually and independently by two of us (K J, L P) using the framework method,9 to understand participants’ perspectives. When there was a difference of opinion between the two reviewers, the issues were discussed until consensus was reached.9

Ten GPs were invited and all agreed to participate: five (two women, three men) from inner Melbourne participated in the focus group; three (all men) from outer Melbourne and two (one woman, one man) from rural Victoria had a telephone interview. All participants had been working in general practice for at least 15 years.

Findings are reported based on the interview schedule’s five topics. Quotes are attributed to participants of the focus group (FG) or those interviewed by telephone (GP).

Participants’ understanding of DTTD varied: some had never heard the term before, while others had an understanding that reflected most of the descriptions found in the literature. Most participants expressed confusion about the various terms used.

… in GP land, it [DTTD] is depression that hasn’t responded to the standard treatment with an antidepressant and some counselling with a psychologist (GP2)

Participants indicated they experienced challenges regarding duration of therapy and response, predictability, complexity, patient-centredness and a lack of acceptance of conventional treatment by patients.

… to me it means that it’s either [that] there are a complexity of factors that compound the treatment plan or that … either I or some other doctor already has had experience with various treatment modalities that have failed or been of limited success (GP5)

In spite of their efforts to understand and manage the condition, including consulting with psychiatrists and other health professionals, participants reported that some patients had suicided.

difficult-to-treat depression

The participants were confused by the various terms used in the literature to describe DTTD. Most had not heard of treatment-resistant depression; one participant suggested that this term was linked to patients’ lack of acceptance of their problem and subsequent non-adherence to medication.

… in fact I even [checked] “Scholared” this afternoon just to make sure it [treatment-resistant depression] was a real entity (FG3)

… treatment-resistant means you’ve gone through a gamut of treatment options and still have major depression symptoms on your hands (GP1)

Most participants had an understanding of treatment-refractory depression. Their concepts of this included insufficient time being allowed for the treatment to improve the patient’s condition. Few participants had heard of treatment-resistant major depressive disorder, and those who had thought it was complex and may be a subtype of major depression. One participant thought the term described patients who had other psychiatric comorbidities.

There was agreement among participants that only a small number of patients present to GPs with DTTD, but that they take up a disproportionate amount of clinician time. Diagnosis was considered difficult, particularly in cases complicated by coexisting conditions.

… I question the initial diagnosis, whether there’s something more going on, or whether there are some other methods of treatment which may be required (GP1)

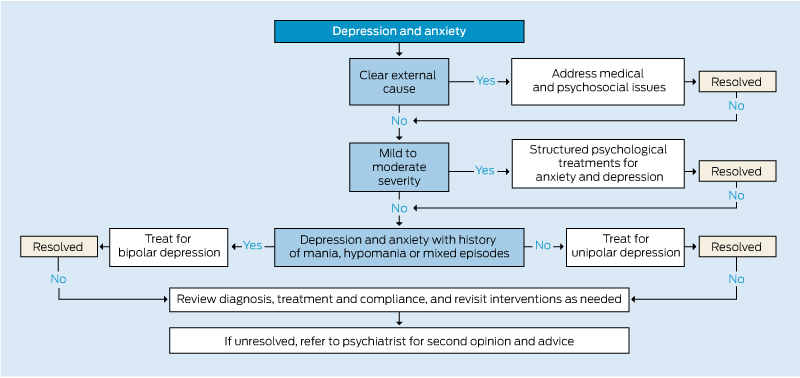

Some participants used management guidelines, such as the DSM-IV, but felt they were not always helpful, as they were difficult to negotiate and apply to particular patients. Others suggested that diagnostic tests have an important role in ensuring any initial diagnosis is correct. The general consensus was that tight diagnostic labels may not help GPs, but that the term DTTD could be useful because it would flag patients who may require input from a specialist.

However, the value of referral to specialists was questioned by some participants.

… just knowing [patients] are difficult to treat doesn’t actually mean that they should go and see a psychiatrist or that going to see a psychiatrist changes the outcome at all. A lot of them, in that more or less major depressive sort of sphere, don’t actually respond to a psychiatrist or psychologist (FG3)

Participants generally felt that their relationship with the patient was important in managing them, but the option of involving family members was not mentioned.

All participants had managed patients with DTTD and often found it difficult.

… ongoing management, even if shared care, is still a difficult proposition (GP1)

… I’m considering a couple of patients with really long-term chronic pain, already on antidepressants; it’s just so hard to sort of tease out their mood and what’s going on (FG1)

Managing these patients was described as a team effort because there can be many exacerbating environmental factors, such as low socioeconomic status, social isolation and relationship conflict, that could be related to poor treatment outcome.

… some of the patients who don’t accept that they have a problem, they are really, really difficult (GP4)

Shared care was valued, particularly for patients who had been hospitalised or who had comorbidities. Participants felt they knew about the patients’ physical and family issues, but their level of concern about patients at risk led them to seek input from experts.

… GPs are much better at individualising treatment based on a bit more [of a] holistic approach, and that’s one reason why it’s difficult to get a treatment algorithm for all very seriously depressed patients (FG3)

Few participants knew about or had used available services, such as the Primary Mental Health Team initiative in Victoria, or government initiatives such as the Mobile Aged Psychiatry Service. Most participants were aware of the Medicare “Better Access” program.

Only one participant had heard of the Wagner chronic illness management model,10 but all acknowledged that a chronic disease management model can be useful in DTTD.

All participants had referred some of their patients with depression to a psychiatrist. Some did so because the patients had multiple needs, others when they felt they needed a psychiatrist’s opinion; some felt referring to a psychiatrist was reserved for severely ill or suicidal patients.

… if I’m getting uneasy, that to me is good enough to call for help, because [of] the consequences, I think [management is] better under specialist care (GP5)

However, accessing a psychiatrist was problematic because of lack of availability, especially of bulk-billing psychiatrists.

… there is a gross limitation of availability [of psychiatrists] in this rural region, so availability is a major issue; so is cost (GP1)

… I work in a bulk-billing practice and patients want to be bulk-billed, and we don’t have enough bulk-billing psychiatrists (GP3)

In the absence of an accessible psychiatrist, some participants used mental health care plans to refer patients to psychologists and social workers. Others used the services of the Primary Mental Health Teams.

… [in my area] for some patients, getting an appointment is a problem because all psychiatrists are private, but various patients now have a mental health care plan and they go to a psychologist (GP4)

… I use the Primary Mental Health Team; it’s a useful concept when, with this sort of complicated cases [and] you’re not quite sure, they will feed back information, then assist you in the management (FG2)

Regardless of cost and accessibility, the relationship between the specialist and the patient was felt to be particularly important.

… a significant challenge is to find a psychiatrist who’s compatible with the patient, and a significant proportion of the people who most need it can’t afford it and then they’ll be at the mercy of the public system, which has very limited access (GP5)

Most participants felt that non-pharmacological or complementary treatments and “lifestyle options” have a role in managing DTTD.

… there are patients who seek alternative treatments like hypnotherapy, St John’s wort, acupuncture, and I suggest lifestyle stuff, setting themselves an agenda for the day (FG5)

… I’ve got somebody [who is] connected with a church, and it’s been a real comfort and help for her, and another who I suggested meditation to (FG1)

This small qualitative study of experienced GPs from urban and rural settings in Victoria raises a number of important issues regarding how GPs evaluate and respond to patients with DTTD.

Although participants demonstrated limited knowledge of the different classifications of DTTD, they had extensive experience in managing and treating patients whose illness was difficult to treat. They had little interest in the nuances of classification, and instead focused on the patient and what to do in practical terms regarding optimal management.

While all participants were aware in general terms of government initiatives that could provide support for patients with DTTD, there were gaps in their knowledge about the specific programs and resources available. Participants were also aware that specialist resources were limited, regardless of location. Thus, they used other management options, including non-pharmacological or complementary treatments. Few were enamoured of existing guidelines, finding them difficult to access and use.

Limitations of this study include the small number of participating GPs and the fact that all were from Victoria. However, they all had extensive clinical experience, and a number of themes relevant to DTTD were raised.

To improve management and treatment of DTTD in both primary and specialised care, resources need to be more available and accessible, including guidelines that are current and relevant to general practice in Australia. Overcoming barriers to accessing specialist and non-medical care should be seen as a priority in assisting GPs to treat patients with DTTD.

more_vert

more_vert