In the mid-1970s, and for a decade, Larry Gostin was an American in London. To anyone living in the UK with an interest in public affairs, Gostin’s name, voice, and words became familiar. First as the legal director of the mental health charity Mind and subsequently as the General Secretary of the UK’s National Council for Civil Liberties (NCCL), he was to be heard pronouncing on knotty issues from psychiatry to surveillance. When he returned to the USA in 1985, Gostin went from taking on the British establishment to taking on the world as he forged a stellar career at the interface between law and public health.

Preference: Psychiatry

913

Woman regains sight in some of her multiple personalities

A woman in Germany who was blind for 17 years has regained her sight, in all but two of her multiple personalities.

The woman, ‘B.T’ suffered an accident in her younger years and gradually lost her vision. According to a study in PsyCh journal, at the time, doctors diagnosed her with cortical blindness from the trauma of the accident.

Years later, she visited Munich psychotherapist Dr Bruno Waldvogel to help with her dissociative identity disorder. Previously referred to as multiple personality disorder, it causes sufferers to have two or more distinct personality types or states. The main cause is severe and repeated trauma in childhood, often before the age of 5.

Dr Waldvogel noted that B.T experienced over 10 different personalities of varying ages, genders, temperaments and other personality traits. Some spoke German, others English and others a mixture of both as she had spent time in her childhood in an English-speaking country.

After four years of psychotherapy, she started seeing letters on a page while she was in one of her adolescent male states. In time, all but two of her personalities were able to regain sight.

An EEG test proved that B.T wasn’t lying about her disability. In one of her two blind states, her brain showed it wasn’t responding to the visual stimuli that sighted people would respond to, despite her looking straight at it.

When she was tested with her sighted personality, her response was normal and stable. They noted in the study that “a switch between these states could happen within seconds”.

Researchers believe that the loss of the woman’s vision was actually of a psychogenic nature and that the two blind personality states are possibly for retreat.

Research author Dr. Hans Strasburger of Ludwig Maximilian University said in an article in Braindecoder: “In situations that are particularly emotionally intense, the patient occasionally feels the wish to become blind, and thus not ‘need to see.'”

B.T.’s case shows that “differences between personality states are not limited to higher-level processing but can differ with respect to the fundamental processing of early sensory information and corresponding perceptual change,” they said. “It therefore provides compelling evidence for the existence of the dissociated identities in a more biological sense.”

Read more about the study in PsyCh Journal.

Latest news:

Life expectancy discussions in a multisite sample of Australian medical oncology outpatients

Why provide life expectancy information? An integral part of patient-centred cancer care is ensuring that information, communication and education provided to patients meets their needs, preferences and values.1 Between 50% and 70% of patients with cancer want numerical estimates of their life expectancy.2–6 Assessing and responding to patient preferences about life expectancy information is therefore a necessary component of patient-centred care, and can assist patients in making informed and effective decisions about their care. Misperceptions of life expectancy by patients, however, can also influence aspects of care, such as decisions about continuing life-prolonging treatments that may diminish their quality of life.7,8

Discussing life expectancy is a complex task. Clinicians must 1) establish how much, and in what detail patients want to know; 2) offer timely information that facilitates decision making about treatment and informed consent; 3) provide information consistent with patient preferences; 4) communicate the limitations inherent to prognoses; 5) present information in formats that aid understanding; and 6) ensure that information is communicated sensitively.6,9 Self-reports by patients about their awareness and understanding of what they have been told about life expectancy arguably comprise the gold standard measure of quality in this area.10,11

Is there concordance between patient preferences and experiences of discussions of life expectancy? The proportion of patients with cancer who reportedly discuss life expectancy is variable. Using direct observation, one study found that 58% of incurable oncology patients were told about life expectancy.12 Lower rates of disclosure (27%–53%) have been reported in studies based on patient self-reports.6,13 While discrepancies between preferences and experiences regarding prognosis information have been reported,6,14 few studies have focused specifically on life expectancy information. One investigation found that 47% of patients who wanted life expectancy information did not receive it, and 4% had received information they did not want.5 The preferences of patients receiving radiation therapy for cancer in Australia regarding who should initiate life expectancy discussions (the patient or their doctor) and their actual experiences were not aligned in 40% of instances.13

Previous studies of this question have been limited by convenience samples or low response rates (24% in one study5), or by including only participants with a single cancer type from a single treatment centre.4 The degree to which these data can be generalised to all cancer patients is therefore questionable. The literature indicates that patients’ preferences and experiences of prognosis discussions may vary according to their age, sex, marital status, ethnic background, education, disease status, time since diagnosis, cancer type and psychological wellbeing.4–6,15,16 Given the emphasis on reducing disparities in health care,1 it is important to explore factors associated with misalignment of patient preferences and experiences, and to identify subgroups who are less likely to receive the desired information.

Our multisite study aimed to identify:

-

the proportion of patients who received their preferred level of life expectancy information; and

-

the sociodemographic, clinical and psychological factors associated with patients’ perceptions of receiving too little, too much, or the desired amount of life expectancy information.

Methods

Patient sample

Eligible medical oncology treatment centres were those providing care for at least 400 new cancer patients each year, and were nominated by state-based research representatives to reflect the relative distribution of public, private, metropolitan and regional hospitals across each of the six Australian states. Invitations were sent to the 51 nominated centres by representatives on behalf of the research team.

Eligible patients had a confirmed cancer diagnosis, were attending the clinic for their second or subsequent appointment (to ensure that patients had experienced cancer care at the centre before answering questions about this treatment), were at least 18 years old, and were able to read and understand English. They were judged by clinical staff to be physically and mentally able to give informed consent and to complete the survey.

Informed consent was obtained by a researcher or clinic staff member by consecutively approaching eligible patients while they waited for their outpatient appointments. To assess consent bias, those who withheld consent were asked to provide their age and sex (this was not done for consenters). Consenting patients were asked to complete a pen-and-paper survey, either in the clinic or at home. Non-responders were sent reminder letters 2–3 weeks and 5–6 weeks after recruitment.

The survey instrument

Development of the measure

Survey items (outcome and associate items) were distributed to a sample of consumer advocates for qualitative feedback on item comprehensibility and relevance. Items were then piloted with 324 patients, and then revised to improve their quality and acceptability. The revised survey (detailed below) was completed by the participants in our study.

Life expectancy item

Participants were asked “Which of the following best describes your experience of discussions with your cancer doctor(s) about how cancer may affect the length of your life (your life expectancy)?” A question stem and five response options were provided: “My cancer doctor(s) at this hospital has discussed or given me …”:

-

More information than I wanted about my life expectancy;

-

All the information that I wanted about my life expectancy;

-

Some of the information that I wanted about my life expectancy;

-

None of the information that I wanted about my life expectancy; or

-

No information about life expectancy, but I haven’t wanted information.

Associate variables

All associate variables were obtained from patient self-reports. Sociodemographic items included sex, age, marital status, education (a proxy for socioeconomic status17), and ethnic background (for participants born outside Australia or who identified as being Aboriginal and/or Torres Strait Islander).

Clinical items included the patient’s most recent cancer type, stage of cancer at diagnosis, current remission status, time since diagnosis, and main reason for visit to the clinic on the day of recruitment.

Psychological wellbeing was measured with the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS), a 14-item survey with two subscales, anxiety and depression. Each item is rated on a four-point scale; scores range from 0 to 21 for each subscale. A mean cut-off score of 8 on each subscale optimises its sensitivity and specificity as a screening instrument.18

Statistical analysis

Stata/IC 11.1 (StataCorp) was used for all analyses. Consent bias (age, sex) was assessed with χ2 analyses. Frequency tables were calculated for each of the five life expectancy response options. A multinomial logistic regression, adjusted for clustering of results within centres by jacknife estimation, examined factors associated with the alignment of patient preference and experience. Key variables were selected a priori. Four preference–experience outcome categories were generated:

-

too much information (“More information than I wanted”);

-

too little information (“Some of the information I wanted” or “None of the information I wanted”);

-

no information wanted or received (“No information about life expectancy, but I haven’t wanted information”); and

-

received all the information wanted (“All the information that I wanted”).

The fourth category was the reference category. While the third and fourth categories both included patients whose preferences and experiences were aligned, the large sample size offered an opportunity to explore these groups separately. Odds ratios (ORs) with 95% confidence intervals and the results of adjusted Wald tests are reported.

Ethics approval

The University of Newcastle Human Research Ethics Committee and the ethics committees of the participating health services approved the study (ref. H-2010-1324).

Results

Of 51 medical oncology treatment centres that were approached, 14 consented to participate in the study (27% consent rate). Two consenting centres did not participate: one had an ethics process that was too expensive, and the other chose not to participate after consenting. Eleven of the participating treatment centres were public medical centres; nine were located in metropolitan and three in regional areas. At least one centre from each Australian state participated. Patients from 11 centres received the survey items on life expectancy during the recruitment period.

Patient sample

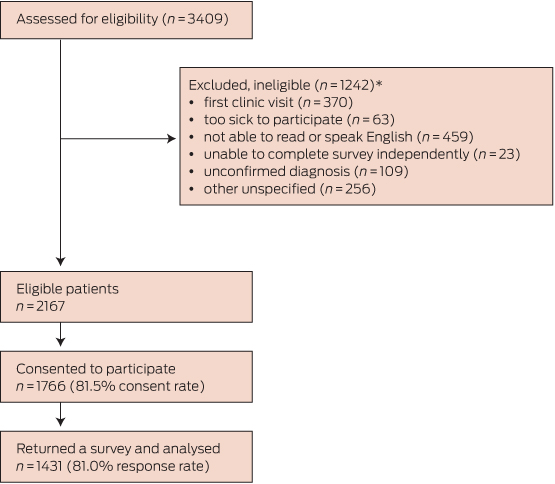

Of the 2167 eligible patients, 1431 returned a survey (Box 1). There were significant sex (χ2[1] = 12.3, P < 0.001; more women) and age differences (χ2[5] = 13.3, P = 0.02; more older patients) compared with those who withheld consent to participate. The age of those who initially consented but later did not respond could not be determined. Box 2 summarises the characteristics of the 1431 participants and the non-consenters.

Do patients receive their preferred level of information about life expectancy?

Of the 1431 responders, 1361 (95.1%) completed the life expectancy item of the survey. Responders did not differ from non-responders with respect to age (χ2[5] = 7.1, P = 0.21), sex (χ2[1] = 2.2, P = 0.14), treatment centre attended (χ2[10] = 13.8, P = 0.18), cancer type (χ2[4] = 4.4, P = 0.36) or remission status (χ2[2] = 0.2, P = 0.91), but participants who did not complete the item were less likely to have had advanced cancer at diagnosis (χ2[2] = 10.7, P = 0.005).

As summarised in Box 3, 72% of patients received the information that they desired; that is, 50% received all the information that they wanted, and 22% neither wanted nor received any information. A mismatch between preferences and experiences was reported by 388 patients (28%), of whom 24% reported not receiving enough information and 4% reported receiving too much.

After adjusting for clustering within treatment centres, no variation between institutions in the perception of life expectancy discussions was identified (post hoc χ2[10] = 35.9, P = 0.21).

What factors are associated with the alignment of preferences and experiences?

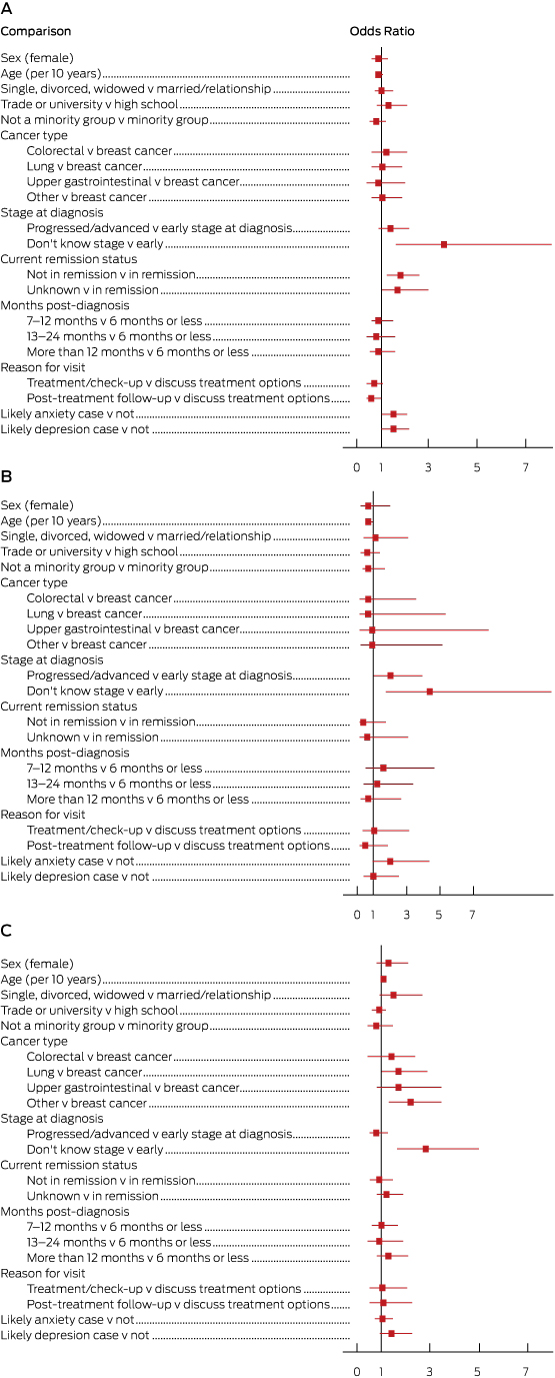

Box 4 and the Appendix present the results of our multinomial logistic regression. The reference group included those who received the desired amount of information about life expectancy. The odds of receiving too little information were greater for patients not in remission (OR, 1.8; 95% CI, 1.2–2.6), who did not know their cancer stage at diagnosis (OR, 3.6; 95% CI, 1.6–8.1), or who were likely to have anxiety (OR, 1.5; 95% CI, 1.0–2.1) or depression (OR, 1.5; 95% CI, 1.0–2.2). Younger patients (OR, 1.4; 95% CI, 1.0–2.0), those with a more progressed cancer (OR, 2.0; 95% CI, 1.0–4.0) or who did not know their stage at diagnosis (OR, 4.4; 95% CI, 1.7–11.8) were more likely to receive too much information. Older patients (OR, 1.1; 95% CI, 1.0–1.2) and those who did not know their stage at diagnosis (OR, 2.8; 95% CI, 1.6–5.0) were more likely to report that they neither wanted nor received information.

Discussion

Do patients receive their preferred level of information about life expectancy?

Almost three in four patients (72%) reported receiving the desired level of information about life expectancy: half of our sample (50%) reported receiving adequate levels of information, while 22% neither wanted nor received any information. This confirms previous findings that patients have different life expectancy information needs.2–5

The degree to which patients receive life expectancy information that aligns with their preferences has not improved dramatically.5 Discordant preference–experience outcomes most commonly involved patients receiving less information than they desired. Clinicians may avoid discussing prognosis and life expectancy in day-to-day practice because of uncertainty about the accuracy of estimates, a perceived lack of time, or concerns about their ability to deal with their patients’ emotions.6,19 Clinicians may wait for patients to request life expectancy information before providing it, or discuss it in ways that may be difficult for some patients to understand.5,6,19 Given that a minority of patients (4%) received more information about life expectancy than they wanted, and a substantial minority prefer to receive no information (22%), it is not appropriate to provide comprehensive information to all patients. Clinicians should take an individualised approach when providing life expectancy information.

Who gets too little information?

Patients not in remission were more likely to receive less life expectancy information than desired. As communicating a poor prognosis is complex, patients may not always understand such information in a manner that aids their decision making.11 As a consequence, clinicians should ensure they have the necessary skills to sensitively provide such information to patients who wish to be informed.20

Elevated anxiety and depression scores were associated with receiving too little information about life expectancy. Clinicians may withhold information from patients whom they perceive to be anxious or depressed, particularly if the prognosis is poor.10 On the other hand, receiving less information than desired may itself increase anxiety and depression.

Who gets too much information?

Patients who received too much life expectancy information were younger and reported having more advanced cancer at diagnosis. This finding may reflect assumptions by clinicians that younger patients will want life expectancy information. It may be especially important for those with a poor prognosis in order to guide decisions about treatment. Our findings may also indicate that clinicians assume that those with a poor prognosis want to receive this type of information.

Who neither wants nor receives information?

Consistent with the results of previous research, patients who neither wanted nor received life expectancy information were significantly more likely to be older.15,21,22 Older patients frequently report higher levels of satisfaction with cancer care.23 Younger patients are more likely to request and receive information about the prognosis,5,20 possibly reflecting increasing expectations of being involved in treatment decisions, and also the potential value of this information for assisting them regain some degree of control over their life plans.6

Stage of cancer at diagnosis unknown

One of the strongest and most consistent associate predictors was not knowing the stage of cancer at diagnosis (9% of sample). These patients had greater odds of reporting that they had received too little or too much information, or that they neither wanted nor received any information. This may reflect a general dissatisfaction with the providing of information, or that cancer diagnosis staging and prognosis was unknown to their doctors. Alternatively, it could reflect a generalised communication problem or the patient’s difficulty in understanding the clinical aspects of their diagnosis. Particular patient groups may need additional support to ensure their accurate understanding of clinical information.

Strengths and limitations of our study

While women were overrepresented and younger patients underrepresented in our sample, this multisite study is the largest and most representative to examine the research question. We are unable to determine whether cancer type profile and other clinical characteristics of the sample are representative of these parameters for the overall population of patients with cancer. While patient reports are the gold standard for assessing patient-centred care,1 they can be influenced by recall bias. Clinical characteristics were assessed by patient self-report, which may be less accurate than data obtained from medical or registry records. However, the clinical items in the survey were pilot-tested and structured to facilitate understanding by patients (lay terms, the use of examples) and to increase accuracy. The participants’ levels of health literacy, which is correlated with information-seeking behaviours and understanding provided information, were not measured, as the study aimed to assess the experiences and preferences of all patients who attended the treatment centres. The preferences of patients and their experiences may change over time as their circumstances change, so that future research should apply a longitudinal study design.

Clinical implications

To improve care delivery, health care teams should regularly collect patient feedback on the quality of care at both the patients’ and the institutional levels. Clinicians could ask patients whether they have received and understood the information about life expectancy provided to them. Enquiring about their information preferences should occur across several consultations to allow patients to process information and to formulate questions.9 At the institutional level, regular feedback about life expectancy information could be incorporated into patient experience surveys. As this study found, asking patients about this topic is practicable and acceptable, but current patient experience surveys do not routinely explore this aspect of care.

It might be expected that delivering information about life expectancy would be a matter of institutional policy. However, the lack of variation across centres suggests that these discussions are regulated by individual clinicians, rather than by policies or monitoring processes. To improve care for the 28% of patients whose preferences and experiences were not aligned, institution-wide policies and routine feedback should be considered.

Conclusions

Discussing life and death is emotional for patients, their families and their friends. That fact that 28% of cancer patients do not receive the level of information about life expectancy that they desire highlights the difficulties associated with discussing this sensitive topic. While not all patients want to receive detailed information, discordance was more often the result of patients wanting more rather than less information. The first step for clinicians should therefore be to ask whether the individual patient wants to know this information, in what format, and at what level of detail (eg, estimated life expectancy, cancer staging, prospects for cure, aim of cancer treatments). Australian consensus guidelines9 are available to assist clinicians in communicating information about life expectancy, including advice about using generic communication skills (eg, body language and active listening), and about clarifying the questions of patients and caregivers and addressing their information needs in an ongoing conversation over time. While the onus of responsibility remains with the clinician to ensure that life expectancy discussions occur in accordance with patient preferences, question prompt lists have been identified as helpful for enabling patients to obtain the information they desire.24

Box 1 –

Patient recruitment and data collection process

* Forty patients were ineligible for more than one reason.

Box 2 –

Sociodemographic and clinical characteristics of the study participants, and age and sex data for non-consenting patients∗

|

|

Study sample |

Non-consenters |

|||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||

|

Total number |

1431 |

401 |

|||||||||||||

|

Sex |

|

|

|||||||||||||

|

Male |

601 (42%) |

200 (52%) |

|||||||||||||

|

Female |

828 (58%) |

184 (48%) |

|||||||||||||

|

Missing data |

2 |

17 |

|||||||||||||

|

Age at diagnosis, years (mean ± SD) |

62.5 ± 12.4 |

|

|||||||||||||

|

18–34 years |

33 (2%) |

16 (4%) |

|||||||||||||

|

35–44 years |

88 (6%) |

17 (4%) |

|||||||||||||

|

45–54 years |

242 (18%) |

57 (15%) |

|||||||||||||

|

55–64 years |

395 (29%) |

120 (31%) |

|||||||||||||

|

65–74 years |

413 (30%) |

100 (26%) |

|||||||||||||

|

≥ 75 years |

206 (15%) |

76 (20%) |

|||||||||||||

|

Missing data |

54 |

15 |

|||||||||||||

|

Marital status |

|

|

|||||||||||||

|

Married or in a relationship |

906 (65%) |

|

|||||||||||||

|

Single, divorced or widowed |

489 (35%) |

|

|||||||||||||

|

Missing data |

36 |

|

|||||||||||||

|

Education |

|

|

|||||||||||||

|

Primary school |

97 (7%) |

|

|||||||||||||

|

High school |

600 (43%) |

|

|||||||||||||

|

Trade or university |

637 (46%) |

|

|||||||||||||

|

Other |

48 (3%) |

|

|||||||||||||

|

Missing data |

49 |

|

|||||||||||||

|

Minority group |

|

|

|||||||||||||

|

Aboriginal and/or Torres Strait Islander |

19 (1%) |

|

|||||||||||||

|

Not born in Australia |

438 (31%) |

|

|||||||||||||

|

Neither |

935 (67%) |

|

|||||||||||||

|

Missing data |

39 |

|

|||||||||||||

|

Cancer type |

|

|

|||||||||||||

|

Breast |

454 (33%) |

|

|||||||||||||

|

Colorectal |

236 (17%) |

|

|||||||||||||

|

Lung |

140 (10%) |

|

|||||||||||||

|

Upper gastrointestinal |

130 (9%) |

|

|||||||||||||

|

Prostate |

78 (6%) |

|

|||||||||||||

|

Other urogenital |

75 (5%) |

|

|||||||||||||

|

Haematological |

60 (4%) |

|

|||||||||||||

|

Gynaecological |

49 (4%) |

|

|||||||||||||

|

Other |

154 (11%) |

|

|||||||||||||

|

Missing data |

55 |

|

|||||||||||||

|

Stage of cancer at diagnosis |

|

|

|||||||||||||

|

Early |

818 (61%) |

|

|||||||||||||

|

Advanced |

408 (30%) |

|

|||||||||||||

|

Don’t know |

117 (9%) |

|

|||||||||||||

|

Missing data |

88 |

|

|||||||||||||

|

Current remission status |

|

||||||||||||||

|

In remission |

409 (30%) |

||||||||||||||

|

Not in remission |

559 (41%) |

||||||||||||||

|

Don’t know |

411 (30%) |

||||||||||||||

|

Missing data |

52 |

||||||||||||||

|

Months since cancer diagnosis |

|

||||||||||||||

|

Less than 6 months |

425 (30%) |

||||||||||||||

|

6–12 months |

260 (19%) |

||||||||||||||

|

13–24 months |

244 (17%) |

||||||||||||||

|

More than 24 months |

473 (34%) |

||||||||||||||

|

Missing data |

29 |

||||||||||||||

|

Reason for clinic visit |

|

||||||||||||||

|

To discuss treatment options |

117 (9%) |

||||||||||||||

|

To receive treatment or check-up during treatment |

801 (61%) |

||||||||||||||

|

Post-treatment follow-up |

405 (31%) |

||||||||||||||

|

Missing data |

108 |

||||||||||||||

|

Treatment received to date† |

|

||||||||||||||

|

Surgery |

977 (70%) |

||||||||||||||

|

Chemotherapy |

113 (81%) |

||||||||||||||

|

Radiotherapy |

664 (51%) |

||||||||||||||

|

Hormonal manipulation |

312 (24%) |

||||||||||||||

|

Biological therapies |

146 (11%) |

||||||||||||||

|

Treatment centre |

|

||||||||||||||

|

A 136 (10%) G |

105 (7%) |

||||||||||||||

|

B 111 (8%) H |

155 (11%) |

||||||||||||||

|

C 159 (11%) I |

163 (11%) |

||||||||||||||

|

D 101 (7%) J |

140 (10%) |

||||||||||||||

|

E 86 (6%) K |

158 (11%) |

||||||||||||||

|

F 117 (8%) |

|

||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||

|

∗ Percentages in this table exclude missing data. † Patients may have received more than one treatment type. |

|||||||||||||||

Box 3 –

Concordance between patient preferences and experiences in discussions of life expectancy∗

|

Category |

Response option |

Number of patients |

% (95% CI) |

||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||

|

Too much information |

More information than I wanted about my life expectancy |

56 |

4% (3%–5%) |

||||||||||||

|

Too little information |

|

332 |

24% (22%–27%) |

||||||||||||

|

|

Some of the information I wanted about my life expectancy |

258 |

19% |

||||||||||||

|

|

None of the information I wanted about my life expectancy |

74 |

5% |

||||||||||||

|

No information wanted nor received |

No information about life expectancy, but I didn’t want information |

298 |

22% (20%–24%) |

||||||||||||

|

The right amount of information |

All the information that I wanted about my life expectancy |

675 |

50% (47%–52%) |

||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||

|

∗Data was missing for 70 patients (4.9%), so that sample size for this table is 1361 patients. |

|||||||||||||||

Box 4 –

Sociodemographic, clinical and psychological factors associated with level of life expectancy information received. A, Too little information received; B, Too much information received; C, Information neither wanted nor received

Odds ratios are shown with 95% confidence intervals; an odds ratio is significant at P < 0.05 if the 95% CI does not include the value of 1. Full data for these plots are included in the Appendix.

Doctors share their tweet-sized mental health stories

Dr Ashleigh Witt is a Melbourne based doctor who is training to be a geriatrician and writes about her experiences on her blog. Follow her on twitter. If you work in healthcare and have a blog topic you would like to write for doctorportal, please get in touch.

A recent discussion through a series of tweets started something wonderful.

In response to our dear twitter friend @ERGoddessMD sharing her brave mental health story here, a discussion about doctor’s mental health began. @iGas2 and myself (with some creative help from @_thezol) dreamed up a hashtag doctors could use to share their tweet-length mental health struggles & triumphs. The hashtag #MH4Docs (mental health for doctors) was thus born.

I didn’t think we’d get this large response – from medical students, to registrars, to consultants in all fields of medicine, from all around the world.

This is the reminder you needed that (despite how it may seem) we all struggle. Whether it’s with that nagging social anxiety, those antidepressants no one knows about, the struggle to keep your head above water during exam time, or how much you need cycling to stay sane. Despite the fact that we might look like perfect, type A, overachievers; doctors are human too.

Here is a growing selection of #MH4Docs confessions with names changed to job titles.

140 characters is nothing, but oh God, it’s everything.

What’s your mental health story in 140 characters or less? #MH4Docs

[Paediatrician] Eating disorder for over a decade; 3 yrs of intensive OP psychiatry input & SSRIs; feeling my brain work again now. #MH4Docs

[Medical Resident] Not many people know that I take mirtazapine, so I can sleep, eat & feel joy in life. I’ve thought all day about whether to tweet. #MH4Docs

[Surgical Registrar] Increasing anxiety in med school + miscarriage = adjustment disorder with 6 mo on antidepressants. After, felt more “me” again #MH4Docs

[GP] 20 years sobriety #MH4Docs

[Medical Registrar] Treatment resistant depression, relapsed because of bullying at work. Lifelong antidepressants & ok with that. #MH4Docs

[ED Consultant] Once spent three days as a voluntary patient. Lithium side effects suck. Things get better #MH4Docs

[ICU Consultant] Depression with severe psychomotor retardation. Losing the ability to speak without great effort is a scary place to be #MH4Docs

[Cardiologist] History of depression controlled well till bullying episodes now getting back to normal spreading the word @beyondblue #MH4docs

[Geriatrician] I fought with depression and anxiety but running, yoga, healthy eating and my family have helped me to stop fighting #MH4Docs

[Med student] Started SSRI + psychotherapy this year for longstanding anxiety. Solid decision, a work in progress. #MH4Docs

[Med student] Battled with anxiety and depression since yr 11. Wouldn’t still be in med without my counsellor, dog, friends, family! #MH4Docs

[Intern] Developed Situational Depression this year due to bullying at work. On SSRIs. Still struggling. Taking it one day at a time. #MH4Docs

[Anaesthetics Registrar] My bestie died in April. He was many things; the best doctor, brilliant, committed, overworked, unsupported, depressed. #MH4Docs

[Medical Student] struggled since teens, attempts at therapy for 4 yrs, finally found right psych this yr & now better than ever #MH4Docs

[Medical Student] Am open re bipolar diagnosis. I was reported as student to med school Professional Behaviour Committee. Was meant supportively, but felt like Typhoid Mary #MH4Docs

[Medical Student] CBT/psychotherapy for mild social anxiety. Took courage to take the first step but my psychologist was wonderful #MH4Docs

[Emergency Consultant] Some days are better than others. Supportive hubby & 4 girls that make my heart swell keep me going #MH4Docs

[Medical Student] Born obsessive compulsive. Battled anorexia. Became happy #MH4Docs

[Emergency Registrar] it’s a rocky, lonely road filled with bouts of anxiety and insomnia #MH4Docs

[Medical Student] Struggled through year 1 and 2 of med with depression and anxiety. It sucked. But learnt to look after my wellbeing = worth it #MH4Docs

[Emergency Consultant] I’m the ultimate cliche: Emergency doc with ADHD. On meds I’m more calm, patient, and focused. #MH4docs

[Geriatrics Registrar] Depression triggered by shift work…factored into my choice of specialty. Was labelled “unreliable” & “emotional” RMO by med admin

[Surgical Registrar] I don’t do very well in winter. Seasonal Affective Disorder means I’m a whole lot better in Australia. #MH4Docs

[Physician] Coming out! Depression since 17. No Rx until 32 because fear of stigma. Still a rocky rd but#MH4Docs ++important.

[Physician] Anxiety for 25yrs +. Some days better than others. Soothed by walking, baking, reading, time with family & friends. #MH4Docs

[ENT surgeon] “Am I good enough? Have I got what it takes to operate on infants & walk with cancer patients at end of lives?” #MH4Docs

[ED registrar] my #MH4Docs story is a long standing eating disorder often triggered by periods of huge anxiety

[Resident] Posting this terrifies me…but recovery from bulimia is one of my proudest achievements. I wish I felt it was ok to talk about it #MH4Docs

[Resident] Antidepressants before Med school, counselling and CBT within Med school, now I look after other’s mental health! #MH4Docs

[Resident] I took a year out of med school, had days off work sick for mental health reasons. Not end of the world & nothing to be ashamed of! #MH4Docs

[GP] Antenatal &Postnatal Depression, Bereavement Reaction&Social Anxiety. 18mos of SSRIs (now finished) then 18mos of therapy (ongoing) #MH4Docs

[Consultant] Depression is devastating & disabling but thankfully I found recovery is possible. It is not a weakness & no-one should be ashamed #MH4Docs

[Medical student] Depression, anxiety, admission. Last one the scariest bc #stigma but I’m well & happy now, abt to graduate! #MH4Docs

[GP] Suicide survivor during med school. On antidepressant meds since 25 yo. Compassionate doctor#MH4Docs

[GP] As stress mounted from work, the arguments increased at home. The game changer in our marriage has been talking to a professional #MH4Docs

Please, keep sharing.

This blog was previously published on Dr Ashleigh Witt’s blog and has been republished with permission. If you work in healthcare and have a blog topic you would like to write for doctorportal, please get in touch.

Other doctorportal blogs

- Oxytocin may benefit some children with autism, but it’s not the next wonder drug

- ‘As an Aboriginal doctor, you bring a unique approach to medicine’

- Sharing the experience of grief from a doctor’s perspective

Oxytocin may benefit some children with autism, but it’s not the next wonder drug

A synthetic version of the “trust” hormone oxytocin, delivered as a nasal spray, has been shown to improve social responsiveness among some children with autism, researchers from the University of Sydney have found.

Published today in the journal Molecular Psychiatry, the trial is the first to rigorously examine the effects of oxytocin over a long time period in young children with autism spectrum conditions (ASC). ASC affect many aspects of a child’s development, including social and communication development.

But while it’s an important step forward, the effects observed in the study are simply too small and too inconsistent – and the stakes are simply too high – for anyone to herald a new autism wonder drug.

Current treatments

Behavioural therapies are considered the first line of therapies for ASC, and on many fronts these have proven to be effective. The drawbacks, which are not discussed as often as they should, are the considerable costs.

Consider for a moment that one recommended regimen of behavioural therapy is upwards of 20 hours per week. Highly trained therapists cost approximately A$150 for every one hour session, and so the financial burden adds up very quickly. Only a small number of families have the capacity to allocate the necessary resources to these kind of programs. This leaves the majority of families seeking therapy alternatives.

The search for effective pharmaceutical therapies is not just due to the financial and time costs associated with behavioural interventions, but also because these behavioural therapies are not highly effective for all children with ASC.

Autism has had a faddish relationship with pharmaceuticals. Numerous drugs over the past half a century have shown promise for benefiting individuals with ASC, and almost instantaneously achieve world-wide fame. But without fail, after further rigorous research, each of these drugs have been found to be no more effective than a placebo.

Other drugs have been found to be ineffective in reducing core ASC behaviours, such as social and repetitive behaviours, but may provide benefits for associated difficulties, such as sleep or anxiety.

Fads come and go. Hope gets raised and inevitably dashed. It was into this landscape that oxytocin began being tested as a potential pharmaceutical for ASC.

What is oxytocin?

Oxytocin is a hormone that affects social cognition and behaviour, and has been the “molecule of the moment” for close to a decade. The human brain produces oxytocin naturally, and is involved in promoting childbirth and lactation reflexes.

Research in ASC has focused on the possible effects of providing the brain with a dose of synthetic oxytocin. In studies of adults, the administration of oxytocin as a nasal spray has been found to improve trust as well as several aspects of social ability, including eye gaze and emotion recognition. These latter abilities are characteristic difficulties of individuals with ASC, and so oxytocin was very quickly examined as a potential pharmaceutical therapy for ASC.

Until this point, studies examining the effects of oxytocin on individuals with ASC have produced contradictory findings. Several research groups have identified small improvements in social behaviours in adults with ASC, while others have identified little to no benefits (in studies of adults children, and adolescents).

The new study

The study included 31 children with an ASC aged between three and eight years of age.

The study used what is called a “cross-over” design, which involves two phases of drug administration. In the first phase, each child is allocated into receiving either oxytocin or the placebo. After five weeks of taking the drug, the groups then switch, so that the group that received the oxytocin in the first phase now receives the placebo, and vice versa for the group that initially received the placebo.

This is a neat design because it means that participants act as their own “control”. This enables scientists to directly compare each child’s abilities after taking oxytocin with their abilities after taking the placebo.

The children received the oxytocin or a placebo through a nasal spray bottle. The placebo looked and smelled exactly like the oxytocin spray, but contained none of this active ingredient. Children received one spray of the relevant bottle in each nostril, morning and night.

Importantly, the study was “double blind”, which meant that neither the family nor the investigators knew what was in the spray bottle during each phase until the conclusion of the trial. After the trial finished, the researchers were “unblinded” to the content of the spray bottles.

The key finding was that the children with ASC showed significant improvements in “social responsiveness” after a period receiving oxytocin, but no improvements after a period receiving the placebo. Social responsiveness refers to abilities such as social awareness, reciprocal social interaction and social anxiety avoidance. In this study, social responsiveness was assessed by the parent using a widely used questionnaire.

However, oxytocin was found to be no more effective than the placebo in its effect on measures of repetitive behaviours and emotional difficulties.

What does this mean?

This was a rigorously conducted trial, and the results indicate that oxytocin may provide small benefits to some children with ASC.

There are limitations to this study that must be acknowledged. While the number of children included in this trial is among the largest of any previous study – particularly given the “cross-over” design, which increases the statistical power – the sample size is too small to make any sweeping conclusions about the importance of oxytocin in ASC intervention.

But the study does provide a strong platform upon which further science can be conducted.

Larger studies of oxytocin as a potential therapeutic for ASC are currently underway in both the United States and Australia, and will provide a greater evidence base in this area, as will studies examining the effect of oxytocin in conjunction with more traditional behavioural therapies.

However, despite these preliminary positive findings, it is important to remain keen observers of the complicated history between ASC and the limited progress into new pharmaceuticals.

And in that context, the decade of research on oxytocin that has preceded this study is highly instructive. Oxytocin may provide benefit to some children with ASC, but it is not a panacea and it cannot yet be recommended for children until further studies are conducted.

![]()

Andrew Whitehouse, Winthrop Professor, Telethon Kids Institute, University of Western Australia and Gail Alvares, Postdoctoral Research Fellow, Telethon Kids Institute

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.

Other doctorportal blogs

- ‘As an Aboriginal doctor, you bring a unique approach to medicine’

- Sharing the experience of grief from a doctor’s perspective

- We’re overdosing on medicine – it’s time to embrace life’s uncertainty

The 12 mental health indicators we should be focusing on

Australia spends $7.6 billion on mental health services annually, but experts question whether anyone is getting better and say we need to change our focus.

“Despite 20 years of rhetoric, Australia’s approach to accountability in mental health is overly focused on fulfilling governmental reporting requirements rather than using data to drive reform,” Sebastian Rosenberg, senior lecturer at the University of Sydney’s Brain and Mind Centre (BMC) and co-authors write in this week’s Medical Journal of Australia.

“The existing system is both fragmented and outcome blind. Australia has failed to develop useful local and regional approaches to benchmarking in mental health,” they say.

They believe that hundreds of mental health indicators and reports should be scrapped and data collection should be refocused into 12 indicators.

These “modest but achievable” indicators would provide a more accurate picture of mental health in Australia.

The group suggests the indicators would “emphasise proximal factors (eg, death rates in the 12 months following discharge from a health facility) that can drive reform, rather than distal outcomes that are likely to reflect more complex determinants acting over longer time frames (eg, life expectancy)”.

The indicators suggested are:

Health domain indicators

- Suicide rate: attempts and completions

- Death rates after discharge from any mental health facility

- Proportion of the population receiving mental health care services

- Prevalence of mental illness

Social domain indicators

- Employment rates

- Education and training rates

- Stable housing

- Community attitudes towards mental illness

System domain indicators

- Experience of care

- Hospital readmission rates

- Life expectancy

- Accessing to specialised programs

“All Australian governments should agree now to refocus their reporting priorities around these 12 indicators. Governance of their collection should reside in a body suitably independent from government which can identify gaps and inequity”, they write.

“Local empowerment is the engine of mental health reform, and timely, useful accountability data are the fuel.”

To read the full article, visit the Medical Journal of Australia.

Latest news:

•Is there value in the Relative Value Study? Caution before Australian Medicare reform

•MBS Review a quick and nasty cost-cutting exercise

•Troponin test concerns

Q&A: Dr Murray Haar, 2010 AMA Indigenous Peoples’ Medical Scholarship winner

Dr Murray Haar is a Wiradjuri man who is currently working at Albury Base Hospital. He won the Australian Medical Association Indigenous Peoples’ Medical Scholarship in 2010. In the lead up to the next round of scholarships being awarded, he reflects on how it helped him and what it’s like being an Indigenous doctor in Australia.

What’s your background and how did you decide you wanted to be in medicine.

I grew up in Punchbowl in Sydney’s south west and I had always wanted to study medicine. I was fortunate enough to go to the UNSW Winter School in years 10 and 12 which spurred my interest. I have always been interested in mental health and hope to specialise in psychiatry.

What was your path to medicine?

I went straight from high school into the medical degree at UNSW in 2008. In that time, I had a year away from study where I worked full time at the Kirketon Road Centre, part of what is known as the ‘injecting centre’ in Kings Cross. There my duties involved engaging with clients in health promotion, needle syringe program, groups and sexual health triage.

I completed my degree in 2014 which had six Indigenous doctors in the graduating class, one of the biggest groups in Australian medicine. I am now doing an internship and residency at Albury Base Hospital which is the county of my father’s people, the Wiradjuri nation.

What area of medicine interests you the most?

I want to do psychiatry to enable me to work in addiction medicine. I have been able to complete a term in psychiatry at Albury and most of my relief term was based in Nolan House, an adult inpatient unit. This experience has really enabled me to work in the area where I feel I have the most potential to make a significant difference in patient care.

Patients with a mental illness are amongst the most disadvantaged people in the community. Psychiatry can play such a powerful role to improve the lives of patients, families and communities.

How did the AMA Indigenous Peoples’ Medical Scholarship help you in your studies?

You need real dedication to study medicine, class contact is five days a week, and there’s heaps of study and preparation after hours. Receiving the scholarship from third year onwards helped me give my studies everything I’ve got, particularly in the last year.

I also got some great help from the UNSW’s Indigenous Unit, Nura Gili which specifically helps Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander students with academic support and assistance navigating the university world.

What advice would you give other Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander students who are thinking of studying medicine?

Don’t listen to anyone who discourages you. There is plenty of support for you, from the university, from scholarships and from other Indigenous doctors. There is improvement in the state of Indigenous health, but the gap is still wide. It’s really important that we play our part in closing it.

What has your experience been of being an Indigenous doctor so far? Are there any unique challenges or advantages?

I am incredibly privileged to be an Aboriginal doctor, particularly when looking after an Aboriginal patient with whom I can empathise and form an instant connection and understanding through our unique appreciation of family and connectedness. The challenges can be tough at time as the workplace is like any other and not free of racism or bullying.

How do you think your perspective or your path to medicine has differed as an Indigenous man?

I feel as an Aboriginal doctor you bring a unique perspective to the practice of medicine. With a set of values and respect for family, land and spirituality and an understanding of the health disparity of our peoples compared to the rest of Australians. There is still much work to be done to close the gap, but more Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander doctors will go a long way to help this.

The next round of AMA Indigenous Peoples’ Medical Scholarship opens on November 1. If you work in healthcare and have a blog topic you would like to write for doctorportal, please get in touch.

Other doctorportal blogs

Signs workforce planning getting back on track

It’s been a chequered time for medical workforce planning in recent years.

Health Workforce Australia (HWA) was a Commonwealth statutory authority established in 2009 to deliver a national and co-ordinated approach to health workforce planning, and had started to make substantial progress toward improving medical workforce planning and coordination. It had delivered two national medical workforce reports and formed the National Medical Training Advisory Network (NMTAN) to enable a nationally coordinated medical training system.

Regrettably, before it could realise its full potential, the Government axed HWA in the 2014-15 Budget, and its functions were moved to the Health Department. This was a short-sighted decision, and it is taking time to rebuild the workforce planning capacity that was lost.

NMTAN is now the Commonwealth’s main medical workforce training advisory body, and is focusing on planning and coordination.

It includes representatives from the main stakeholder groups in medical education, training and employment. Dr Danika Thiemt, Chair of the AMA Council of Doctors in Training, sits with me as the AMA representatives on the network.

Our most recent meeting was late last month, and the discussions there make us hopeful that NMTAN is finally in a position where it can significantly lift its output, contribution and value to medical workforce planning.

In its final report, Australia’s Future Health Workforce, HWA confirmed that Australia has enough medical school places.

Instead, it recommended the focus turn to improving the capacity and distribution of the medical workforce − and encouraging future medical graduates to train in the specialties and locations where they will be needed to meet future community demands for health care.

The AMA supports this approach, but it will require robust modelling.

NMTAN is currently updating HWA modelling on the psychiatry, anaesthetic and general practice workforces. We understand that the psychiatry workforce report will be released soon. This will be an important milestone given what has gone before.

Nonetheless, it will be important to lift the number of specialties modelled significantly now that we have the basic approach in place, so that we will have timely data on imbalances across the full spectrum of specialties.

The AMA Medical Workforce Committee recently considered what NMTAN’s modelling priorities should be for 2016.

Based on its first-hand knowledge of the specialities at risk of workforce shortage and oversupply, the committee identified the following specialty areas as priorities: emergency medicine; intensive care medicine; general medicine; obstetrics and gynaecology; paediatrics; pathology and general surgery.

NMTAN is also developing some factsheets on supply and demand in each of the specialities – some of which now available from the Department of Health’s website (http://www.health.gov.au/internet/main/publishing.nsf/Content/nmtan_subc…). I encourage you to take a look.

These have the potential to give future medical graduates some of the career information they will need to choose a specialty with some assurance that there will be positions for them when they finish their training.

Australia needs to get its medical workforce planning back on track.

Let’s hope that NMTAN and the Department of Health are up to the task.

Using accountability for mental health to drive reform

Across the health care system, accurate measurement and frequent transparent reporting of patient experiences has the capacity to reduce variations in care and increase effective service provision.1 The merit of applying this principle to mental health is well understood.2,3 Over 20 years, four successive national mental health plans have each called for this kind of accountability. Despite the rhetoric, and as we now brace for a fifth plan, Australia still has no agreed set of priority indicators nor any process to enable useful benchmarking.

This is a critical management deficiency recognised by the National Mental Health Commission and the Mental Health Commission of New South Wales, which have both recently (and separately) published sets of preferred key indicators.4,5 Repeated Australian reports and reviews suggest mental health services are still best characterised as fragmented,6 bedevilled by major gaps in provision,7 inequitably distributed,8 increasingly costly (http://mhaustralia.org/submission/mental-health-australia-submission-senate-inquiry-extent-income-inequality-australia) and outcome blind.9

Australia’s current data collection systems focus on activity rather than outcomes and are typically aggregated to state and national levels. Local opportunities for benchmarking are limited to comparing inputs and processes, such as bed numbers and length of stay, and have not evolved to permit comparison of outcomes. Previous attempts to develop nationwide approaches to data definitions and reporting have proven a glacial (and expensive) affair. We propose a new, limited set of indicators for mental health that have the capacity to drive reform.

These should not only be useful nationally but also regionally. Evidence of the utility of such regional comparisons is strong and growing.4,10 There are significant regional differences in relation to issues such as suicide and rates of access to mental health care. Data need to be available at this level, rather than just statewide, to permit useful comparisons and propel reform.

An additional consideration is that the chosen indicators must reflect the broader concerns of the community and the validated experience of consumers, carers and service providers. Current data collections focus on governmental reporting requirements and do not reflect the social priorities that are evident in mental health care, such as in relation to social participation, employment and homelessness.

In proposing specific indicators, we build on our previous proposals on national service priorities.3 We propose 12 indicators across three domains (health, social and system reform), consistent with the core value of the National Mental Health Commission — the right to lead a contributing life.

The indicators emphasise proximal factors (eg, death rates in the 12 months after discharge from a health facility) that can drive reform, rather than distal outcomes that are likely to reflect more complex determinants acting over longer time frames (eg, life expectancy).

The 12 indicators are set out below, with a brief outline of current data and any limitations in relation to their current collection or use.

Health domain indicators

Suicide rate: attempts and completions

These data are already collected and reported, including in relation to the Indigenous community where the problem is acute.11 Data on suicide attempts are not available in Australia, unlike elsewhere.12 Data on completed and attempted suicides are needed at the regional level to support local, tailored prevention activities. In 2003, there were 2214 suicides and in 2013, there were 2522.13 By comparison, a national campaign has seen the road toll decrease from 1621 in 2003 to 1156 in 2014.14

Death rates < 3 and < 12 months after discharge from any mental health facility, including cause of death

These data are not collected, with infrequent exceptions.15 Cause of death permits new, vital linkage of mental and physical illness, critical given the frequency of comorbidities.

Proportion of the population receiving mental health care services — both among the general population and, specifically, the population aged 12–25 years

These data are already collected and reported every decade. There is recent evidence indicating some lift in the rate of overall access to care, mainly due to the Better Access to Psychiatrists, Psychologists and General Practitioners through the Medicare Benefits Schedule initiative,16 now costing around $15 million per week.17 However, with 75% of all mental illnesses manifesting before the age of 25 years,18 it is vital also to monitor access by young people,19 including to new e-mental health, early intervention and online services.20 For young men, the access rate is as low as 13%. This indicator would help to track whether services designed to meet the needs of young people were reaching their target audience.

Prevalence of mental illness

Prevalence data are already collected every decade. It would be useful to present these data by region in future iterations, to build understanding of comparative community resilience and vulnerability, and to better target resources where they are needed most.

Social domain indicators

Participation rates by people with a mental illness of working age in employment

Having a job is critical to the health, welfare and dignity of people with a mental illness.21 Addressing unemployment and minimising welfare spending has been a clear social priority for successive governments. Despite this confluence of interests, there is no current specific national data collection. The Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development ranks Australia lowest in terms of the income of people with a severe mental disorder as a ratio of the average income of the population.22

Participation rates by people with mental illness aged 16–30 years in education and training

When young people are exhorted to “earn or learn”, it is critical to monitor their education outcomes. This is being done elsewhere (eg, the United Kingdom Office for National Statistics) but not in Australia.

People with a mental illness reporting they have stable housing

Each night, 105 000 Australians are homeless.23 It is estimated that more than a third of people who are homeless in inner city areas have severe mental illness.24 There is currently no specific data collection. Discharge into homelessness still occurs. These data would tell us about the impact of housing and supported accommodation services.

Community surveys of attitudes towards mental illness

Recovery is more likely when clinicians and service providers understand the social realities that people with a mental illness face in their daily lives.25 Community education campaigns help to demystify mental illness and counter stereotypes.26 Although some information exists, there is no regular national survey of community (and business) attitudes and stigma towards mental illness.

System domain indicators

Consumer and carer experience of care

Patient satisfaction is one of the core ingredients in making a service system accountable, transparent and responsive.9,27 There are no nationwide validated data collected on the experience of care of mental health consumers and carers.

Readmission rates to hospital or re-presentation to emergency departments within 28 days after discharge

Some readmission data are already reported. In 2010–11, the proportion of admissions to state and territory acute psychiatric inpatient units that were followed by a readmission within 28 days was 15% nationally.28 This figure has been stable since 2005–06. This indicator would enable detailed comparison of the approach taken to arranging community support on discharge from one region to another.

Life expectancy for people with severe and persistent mental illness

This measure has been reported previously, with the life expectancy of this cohort much shorter than that of the general community.29 This indicator would highlight the extent to which the mental health care system is addressing the complex needs of the cohort, managing both physical and mental health issues, housing and other matters.

Number of people accessing specialised programs to enhance economic and social recovery

In the community-managed mental health sector, no service-level data are currently reported. This measure would at least monitor whether the community mental health sector is becoming a more significant player in Australia’s mental health system.

Conclusion

There are clearly other areas of interest beyond the indicators listed here, including smoking rates, comorbidities and cost. There would also be considerable merit in tracking spending on mental health research so as to gauge our capacity to innovate.

There are currently hundreds of mental health indicators and multiple reports. We contend that very little of this information is used or usable at the local level to drive reform, and that much of this data collection should cease. All Australian governments should agree now to refocus their reporting priorities around these 12 indicators. Governance of their collection should reside in a body suitably independent from government which can identify gaps and inequity. This was an essential role played by the New Zealand Mental Health Commission30 but is yet to emerge in Australia.

It is critical that these indicators do not sit apart from a new, system-wide process of continuous quality improvement in mental health care and suicide prevention. No such process currently exists. This focused approach, around 12 agreed indicators, should drive quality improvement by making data available at the regional level for benchmarking by service providers, funders, decision makers and, importantly, consumers and carers. Every community wants to know the extent to which it has a mental health system on which it can rely. Local empowerment is the engine of mental health reform, and timely, useful accountability data are the fuel.

A further step would be to set some targets for these measures that reflect the scope and ambition of mental health reform in Australia. Across a myriad mental health plans and policies, this is yet to be articulated and is now long overdue.

Legal criteria for involuntary mental health admission: clinician performance in recording grounds for decision

In enacting mental health laws, parliaments empower doctors and other health professionals to detain patients and coercively administer treatment in defined circumstances. These laws have been informed by the United Nations Principles for the Protection of Persons with Mental Illness and the Improvement of Mental Health Care (1991).1 These principles include requirements that patients be treated in the least restrictive environment (principle 9), and that every effort be made to avoid involuntary admission (principle 15). Laws made in recent years also purport to give effect to the articles in the 2006 United Nations Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities.2 Australia is a signatory to this convention.

Principle 16 of the 1991 UN catalogue requires that, when involuntary admission occurs, the grounds of the admission be communicated to the patient without delay, and the fact of the admission and the grounds for admission be communicated to the patient’s personal representative, the patient’s family (unless the patient objects) and a legal review body.1

In South Australia, the grounds for involuntary admission were previously recorded on the initial detention form, as required by a regulation of the SA Mental Health Act 1993. The form had space for a brief statement of the grounds for detention. It was expected that, if practicable, a psychiatrist would then examine the patient within 24 hours. It was not required that a copy of the form be given to the patient.

In 2010, the Mental Health Act 2009 came into operation. This new Act requires the order for involuntary admission to be given to the patient, together with a statement of their rights. It was expected that by receiving a copy of the order, patients, carers and the tribunal would be informed of the specific grounds for their detention, as this had previously been included in the order. However, the Minister for Mental Health had removed the requirement for grounds to be documented on the form.

In 2014, the SA Office of the Chief Psychiatrist published a review of the operation of the Act in which the requirement for the inclusion of written reasons on orders was reconsidered. It was recommended that reasons for detention not be included in the form.3 The SA Government is currently considering the outcomes of this review.

In the context of the current policy and legal debate about requiring doctors and other medical practitioners to succinctly document grounds for involuntary treatment on a form, our study examined how effectively doctors have complied with this legal requirement in the past. This has been done by rating forms for inpatient detention completed by medical practitioners under the former Mental Health Act 1993 for compliance with legislative criteria.

Methods

We analysed 2491 consecutive forms authorising the initial detention of involuntary patients. These forms had been faxed to the Guardianship Board of South Australia from hospitals that admitted involuntary patients during the period 17 July 2008 – 15 June 2009.

One of us (K R), a legal researcher, reviewed the forms to assess compliance with the requirements of the Mental Health Act 1993. An initial trial rating of 250 forms was completed before undertaking the analysis of all the documents.

The grounds for detention were defined in section 12(1) of the Mental Health Act 1993:

(1) If, after examining a person, a medical practitioner is satisfied—

(a) that the person has a mental illness that requires immediate treatment; and

(b) that such treatment is available in an approved treatment centre; and

(c) that the person should be admitted as a patient and detained in an approved treatment centre in the interests of his or her own health and safety or for the protection of other persons, the medical practitioner may make an order for the immediate admission and detention of the person in an approved treatment centre.

The Mental Health Act 1993 “Order for admission and detention in an approved treatment centre” (Form 1; reproduced in the Appendix) cites these legislative criteria and allows space for the examining physician to enter the reasons for detention.

We adopted a generous rating approach, in that we accepted any evidence that each criterion had been addressed by the practitioner, without seeking to determine whether a threshold level for the criterion had been met (eg, assessment of the degree of risk).We rated a criterion as having been met if it was referred to in writing in the reasons given, or if the criterion printed on the form was clearly marked up (eg, with a circle, underlining or tick) to indicate that the practitioner had considered that criterion.

Mention of a current illness, such as depression, schizophrenia or psychosis, was accepted as the presence of a mental illness.

The Act required that treatment be available in a treatment centre. This criterion was not assessed, as, if a person had been detained, treatment would be made available; if a bed in a ward was not available, a patient would be accommodated in an emergency department.

In assessing the forms, an overall statement of their compliance with legal criteria was made. Forms were assessed as clearly meeting the criteria if they addressed all the criteria required by the legislation (the detainee has a mental illness; is a risk to himself or to others; and requires immediate medical treatment). In some forms, not all criteria were explicitly addressed, but what was written and marked up constituted a justification for detention, and the form was therefore classified as “otherwise meets criteria”.

Ethics approval

The project was undertaken with the approval of the South Australian Department of Health Research Ethics Committee (HREC/14/SAH/129).

Results

Of the 2491 forms reviewed, only 985 (40%) addressed all the necessary legal criteria for detention (Box 1). Specifically, 1471 forms (59%) did not refer to a need for immediate treatment, 540 forms (22%) did not refer to the presence of a mental illness, and in 359 forms (14%) there was no reference to risk to self or to others (Box 2).

With regard to risk, 1247 forms (50%) recorded risk to self but not to others, 718 (29%) risk to both self and to others, and 167 (7%) risk to others but not to self.

On some forms, it was possible to infer that all criteria had been addressed even though this was not explicitly stated. If forms that “otherwise met criteria” in this manner were included, the number of those assessed as addressing the legal criteria increased to 1249 (50%). This group included 193 forms in which the assessor made a note that a need for immediate treatment could be inferred from the other details recorded on the form, although the need for immediate treatment was not specifically mentioned.

As the majority of practitioners did not refer to the need for immediate treatment, a further descriptive analysis was undertaken after removing this element, and this indicated that 1697 forms (68%) explicitly addressed the remaining criteria: the presence of mental illness and risk to self or others (Box 3).

Discussion

In providing written grounds for the detention and involuntary treatment of their patients, medical practitioners addressed all necessary criteria on only 40% of the admission forms. We view this very low completion rate as a significant problem in documenting evidence of compliance with the law and protecting the rights of the affected patient. However, when the criterion that was most poorly addressed (the need for immediate treatment) was removed from analysis, the rate of compliance with the remaining criteria increased from 40% to 68%. This is reassuring.

Nevertheless, these results raise a significant question about the legality of the involuntary admission of those for whom the criteria were not addressed on the form. Does the fact that criteria were not specifically addressed reflect the actual clinical circumstances of the patient, or simply an error of omission by the clinician when completing the form? To answer this question it would be necessary to compare the information on the form with other sources, such as case notes or patient interviews. This was not part of our study.

A strength of our analysis was the large number of forms assessed. In theory, the examined collection should represent every mental health detention in SA between 17 July 2008 and 15 June 2009. We are nevertheless aware that some hospital units may not have complied with the requirement to routinely fax forms to the Guardianship Board. The detaining medical officer was not responsible for faxing forms, however, so we do not believe that lapses in doing so by some units would bias the outcome of our analysis.

Completion of forms

Given that mental health laws seek to limit the use of coercion to defined situations, the requirement to succinctly state the grounds for taking this action should protect the rights of patients if the defined grounds are not present. The discipline of completing the form, a skill that requires the integration of clinical findings with legal requirements, can, arguably, assist with this clinical decision making. The legal requirement to complete the form also accurately reflects the gravity of the loss of liberty for the patient, which is comparable with other forms of custody, including police arrest.

Variability in decision making

It is worrying that decisions to make orders may be made for extra-legislative rather than legal reasons. Variability in decision making about the need for an order can be attributed to the level of training of clinicians and to the individual clinician’s attitude to risk.4 Some extra-legislative factors may be clinically relevant, such as non-compliance of the patient and their lack of insight,5,6 although they ultimately influence the assessment of risk within the context of the defined criteria.

There is also a potential for clinicians to substitute their own moral judgement for what the law requires. This has been discussed in the context of experts who testify in forensic matters “… in accordance with their own self-referential concepts of ‘morality’ and openly subvert statutory and caselaw criteria that impose rigorous behavioral standards as predicates for commitment”.7

A recent report of in-depth interviews with 10 Norwegian psychiatric clinicians about how legal criteria are interpreted suggested that an ideal rational deliberation can lapse into paternalism, with assumptions made about lack of insight and the pointlessness of attempting to provide voluntary care for people with severe mental illness.8 Another author identified the risk of applying a false “ordinary common sense” to decision making in the law; this can nurture irrational, unconscious, bias-driven stereotypes and prejudices.9

Whether a requirement for clinicians to succinctly document grounds for involuntary admissions would rectify the problem of extra-legislative decision making is not known. It is still possible to apply extra-legislative criteria in making a decision, and to then retrospectively justify it by correctly citing the law in recording the decision.

In SA, patients are no longer provided with grounds for their detention. It must now be very difficult to detect whether criteria for detention under the Mental Health Act 2009 have been addressed. Patients would be better protected by a requirement that the grounds be recorded at the time of detention.

Other jurisdictions in Australia have a variety of laws regarding the completion of forms and the notification of involuntary patients. All except the Australian Capital Territory and SA require a form that includes the grounds for detention. New South Wales, the Northern Territory, Queensland, Victoria, Tasmania and Western Australia require that people who are involuntarily detained be informed either of the fact of their detention and their rights, or of the reasons for their detention.10–15 The manner in which they must be informed, however, differs. In the NT, involuntary patients may be informed orally or in writing, although a record of the notification must be made.11 In Queensland,16 Victoria13 and NSW,10 involuntary patients are informed in writing; in Tasmania, the legislation provides a right to be informed, but does not specify how involuntary patients are to be informed.17

We do not have a uniform system of counting and reporting inpatient detention rates.18–20 The Australian Institute of Health and Welfare refers to general trends (eg, 29.0% of public hospital admissions of patients with psychiatric symptoms in Australia during 2011–12 were involuntary), but it cautions that direct comparisons between service settings can be affected by differences in data collection standards and methods.19 In SA, statistics on the number of involuntary orders in emergency departments and wards are now available,21 but there is no usable denominator that would allow the calculation of rates and accurately attribute meaning to yearly fluctuations.

Light and colleagues22 highlighted a similar problem with respect to involuntary community treatment orders, noting the lack of a comprehensive, uniform national dataset and the need for rigorous and publicly accessible policy on their use. The same can be said for the reasons for inpatient compulsion. The collection of this information would allow links between rates of compulsion and the practices and culture related to documenting the grounds for detention to be explored.

Should admission forms include the grounds for involuntary treatment?