The known The number of vulvoplasty procedures in NSW has been rising over the past decade.

The new One in 23 women who had vulvoplasty had repeat procedures; one in ten had had, or will have, other cosmetic surgery. One in 14 procedures resulted in serious adverse events. The caesarean delivery rate for primiparous women was about 30% higher among those who had had vulvoplasty. Vulvoplasty had no effect on perineal outcomes of a subsequent vaginal first birth.

The implications Our population-based study provides important information that can inform pre-surgery counselling.

Vulvoplasty refers to surgery performed on the external female genitals, generally reducing the size or correcting the asymmetry of the labia minora.1 Increasing demand for this procedure has been reported over the past two decades, with the number of procedures rising in high income countries, including Australia,1 the United Kingdom2 and the United States.3

In Australia, the number of Medical Benefits Schedule (MBS) rebates linked with item number 35533 for vulvoplasty procedures doubled from 744 during 2003–04 to 1588 in 2012–13.1 This MBS item was specifically intended to cover medically indicated vulvoplasty procedures performed in or out of hospital in private care. However, as no guidance or objective measures for assessing medical necessity were available to clinicians, concern was raised that the increasing number of rebates claimed might reflect demand for vulvoplasty as a cosmetic service.1

A review of vulvoplasty services was consequently undertaken by the federal Department of Health,1 and changes to the MBS were made. The former Medicare item number 35533 (vulvoplasty) was replaced in November 2014 by two item numbers: 35533 (surgical repair of female genital mutilation and major congenital anomalies) and 35534 (surgical repair for localised gigantism causing significant functional impairment).4 Rebates were no longer available for out-of-hospital services, and were available for item 35534 only when there was documented evidence of a clinical need.4

The Department of Health review incorporated both Medicare data and information from the National Hospital Morbidity Database (NHMD). The NHMD contains data for vulvoplasty procedures in public and private hospitals and in day-stay units, with or without a medical indication, and provides additional information about the hospital stay. The review also reported the associated principal diagnoses and age profiles of patients at the time of vulvoplasty. However, as data were for procedures and not for individual women, analysis of re-admissions and repeat procedures was not possible. Apart from age, neither the characteristics of women undergoing vulvoplasty nor rates of adverse outcomes were reported. No other studies have had the capacity to investigate outcomes at the population level.

The increased number of vulvoplasty procedures has attracted discussion and debate in both the medical community and the popular media.5,6 Commentators have explored possible reasons for the rise,1,7,8 as well as the ethics of cosmetic surgery marketing.7,9–11 The low level of evidence for the reported short and long term outcomes, including adverse events, has been criticised.1,8,9,11,12 Studies have relied on surgeon-initiated questionnaires9,13 or anecdotal and case reports.11,13 Further, no studies of the effects of vulvoplasty on subsequent childbirth have been undertaken.13,14

The aims of our study were to compare the characteristics of women undergoing vulvoplasty with those of other women of reproductive age; to quantify serious short term adverse events; and to determine the effect of vulvoplasty on subsequent outcomes for women giving birth. We hypothesised that vulvoplasty might have an impact on perineal trauma and decisions about the mode of delivery.

Methods

The study population consisted of all women of reproductive age (15–54 years) who had had a vulvoplasty in a New South Wales hospital during 2001–2013. To explore the relationship between vulvoplasty and subsequent birth outcomes (birth type and perineal status), we also analysed a subpopulation that included women who had undergone vulvoplasty and subsequently given birth for the first time during 2001–2012.

Data were obtained from two routinely collected population-based data collections: the NSW Admitted Patients Data Collection (APDC, “hospital data”) for 2001–2013, and the NSW Perinatal Data Collection (PDC, “birth data”) for 1994–2012. The APDC, an administrative data collection, is a census of discharges from all public and private hospitals and day procedure centres. As well as demographic data, it includes clinical diagnoses coded according to the International Classification of Diseases, tenth revision, Australian modification (ICD-10-AM), and procedures coded according to the Australian Classification of Health Interventions (ACHI; based on the MBS).15 The NSW PDC is a statutory dataset with information for all births in NSW of at least 20 weeks’ gestation or in which the birthweight was at least 400 g. It contains demographic, medical and obstetric information, as well as details about labour, birth and infant condition. Longitudinal linkage of the hospital records and birth records was undertaken by the Centre for Health Record Linkage, enabling admissions, re-admissions, serious adverse outcomes and birth outcomes for individual women to be analysed. The linkage rate between hospital and birth data for mothers has previously been reported as 98.1%.16 De-identified records were provided to the investigators.

Vulvoplasty was identified by ACHI procedure code 35533-00 in the hospital data. The principal diagnosis at the time of each vulvoplasty was identified by ICD-10-AM diagnostic codes.

Factors potentially associated with vulvoplasty and available in hospital records for analysis included age, marital status, smoking history, country of birth and socio-economic status (residential postcode was used to classify each woman according to the Socio-Economic Indexes for Areas [SEIFA] Index of Relative Socio-Economic Disadvantage17). Data on cosmetic breast augmentation (for women without prior mastectomy or breast cancer), liposuction, and face or brow lifting were also included in the analysis if the procedures had been undertaken during the study period.

Information about the vulvoplasty procedure and health service factors included hospital location, whether the woman had received public or private care, how many nights she had spent in hospital, the use of general anaesthesia, and whether she had been re-admitted to hospital within 14 days of the vulvoplasty surgery. Serious adverse events and complications ascertained from hospital records included haemorrhage, infection, and adverse urinary tract events, all of which have previously been reported in smaller, non-population studies.7 Information ascertained from the birth data included birth mode (non-instrumental vaginal, forceps, vacuum, and intrapartum or pre-labour caesarean delivery), episiotomy, and degree of perineal trauma.

The total number of vulvoplasties and the change in number over time were calculated for public and private hospitals, with the overall annual change estimated by Poisson regression. The characteristics of women with a first record of a vulvoplasty were described, and compared with 2011 NSW reference populations of all women aged 15–54 years (N = 1 982 710), including Australian census data for age and marital status18 and Australian migration data for country of birth.19 Data from the NSW Population Health Survey for women aged 15–54 years (N = 3258) were used as reference population data for smoking status.20 Rates of other cosmetic procedures were determined for all women of reproductive age who had no record of vulvoplasty and had been admitted to hospital for any other reason during the study period (N = 2 053 760), and compared with those for women who had undergone vulvoplasty. The characteristics of the vulvoplasty procedures and associated health service factors are described.

Women with a primiparous birth after a vulvoplasty were identified, and their birth characteristics compared with primiparous women without prior vulvoplasty by χ2 analysis. Primiparous women were chosen for this analysis to minimise any obstetric history effect on birth outcomes.

Ethics approval

Ethics approval for the study was obtained from the NSW Population Health and Health Services Research Ethics Committee (reference, 2012-12-430).

Results

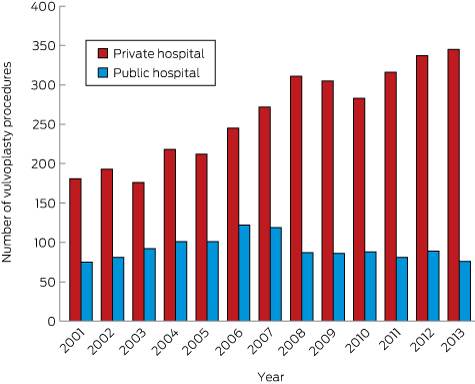

During 2001–2013, 4592 vulvoplasty procedures were performed on 4381 women in NSW hospitals and day-stay centres; 1198 were performed in public hospitals, 3394 in private hospitals. The number performed in public hospitals peaked in 2006 (122 procedures), while the number performed in private hospitals was still rising in 2013 (345 procedures) (Box 1). Of the 4381 women, 4193 (95.7%) had had only one vulvoplasty, 170 (3.9%) a total of two vulvoplasties, and 18 (0.4%) three or more. The total number of procedures rose from 256 in 2001 to 421 in 2013, a total increase of 64.5% and an annual increase of 3.3% (95% CI, 2.5–4.2%).

The two most frequent principal diagnoses linked with vulvoplasty were “hypertrophy of vulva” (26.1% of procedures in private hospitals, 23.1% in public hospitals) and “non-inflammatory disorders of vulva or perineum” (19.7% in private hospitals, 21.2% in public hospitals). “Plastic surgery for unacceptable cosmetic appearance” was the third most frequently cited indication in private hospitals (8.1%), and 23rd for procedures in public hospitals (0.7%).

Compared with the general population of NSW women aged 15–54 years, more women undergoing a first vulvoplasty were born in Australia (74.6% v 67.6%) and were 25–34 years of age (32.6% v 25.2%); fewer were married or in de facto relationships (42.5% v 55.4%) or aged 45–54 years (16.3% v 25.5%). A higher proportion lived in areas of higher socio-economic status, and six times as many had other cosmetic procedures performed during the study period (Box 2).

Most vulvoplasty procedures were performed in private hospitals in Sydney (59.4%); 13.9% were performed in public hospitals in Sydney, 14.5% in private hospitals outside Sydney, and 12.2% in public hospitals outside Sydney (Box 3). Most women (68.9%) had a day-only admission. Of the 679 women (14.8%) who were in hospital for two nights or more, 365 (53.7%) had gynaecological surgery other than vulvoplasty recorded as the principal procedure, including repair of uterine prolapse, pelvic floor or enterocoele (156 women), and vaginal hysterectomy (101 women).

Serious adverse events at the time of the vulvoplasty admission or during re-admission within 2 weeks of the initial admission were associated with 332 procedures (7.2%). For vulvoplasties with concomitant gynaecological surgery, the serious adverse event rate was 12.7%; for other vulvoplasties it was 5.0%. The most common events were urinary tract problems and complications (54.5% of complications; Box 3). One hundred and twenty-one women (2.6%) were re-admitted to hospital within 2 weeks of the procedure, with haemorrhage or haematoma complicating a procedure (30 women) and a variety of diagnoses related to wound complications or infection (29 women) being the most frequent principal diagnoses. A total of 4.3% of women had repeat vulvoplasties, with seven having a repeat procedure within 2 weeks of the first.

Of all vulvoplasty procedures, 3157 (68.7%) were for women who had not previously given birth in NSW. Women with one prior birth accounted for 694 of all vulvoplasties (15.1%), women with two prior births for 494 (10.8%), and women with three prior births for 247 procedures (5.4%).

Two hundred and fifty-seven women with a history of vulvoplasty subsequently gave birth for the first time during 2001–2012. The proportion of these women who had a caesarean delivery (40.0%) was significantly greater than for the 454 027 primiparous women with no history of vulvoplasty (30.3%; χ2 test, P < 0.001). This difference was evident for births in both private hospitals (56% v 39.7%; χ2 test, P = 0.004) and public hospitals (33% v 27.0%; χ2 test, P = 0.04). A higher proportion of women with prior vulvoplasty had a pre-labour caesarean delivery than other women (20% v 11.0%), while the rates of intrapartum caesarean delivery were similar (20% v 19.3%). For vaginal births, there were no significant differences in the episiotomy rates or in perineal trauma for primiparous women with and without previous vulvoplasty (Box 4).

Discussion

The annual number of vulvoplasties performed in NSW hospitals on women aged 15–54 years increased by 64.5% between 2001 and 2013. However, the majority of Australian providers who advertise vulvoplasty surgery services indicate that these procedures are performed on an outpatient basis under local anaesthetic.1 During the same period, Medicare rebate data for NSW (which also captured clinically indicated, out-of-hospital procedures) indicated a 142% increase in the number of procedures, suggesting marked increases in the numbers of vulvoplasty procedures both in and out of hospital.21 Following changes to the MBS in 2014, restrictions of the eligibility for Medicare rebates for these procedures were tightened. The number of vulvoplasties recorded by Medicare subsequently declined, with 240 rebates paid in NSW in 2015, compared with 448 in 2013.4 Data have never been available for cosmetic out-of-hospital procedures (ie, those that are not clinically indicated), so that the total number of vulvoplasty procedures performed cannot be determined.

It is unlikely that a rise in the incidence of vulval pathology is driving the increase in surgery, and we cannot determine whether any vulvoplasties undertaken in NSW hospitals were for reversal of female genital mutilation. Dissatisfaction with physical aspects (such as chafing and discomfort), the appearance of their genitalia or with sexual activity, and feeling abnormal are reported as motives for women requesting surgery.13,22 However, there is a great deal of variability in normal vulval anatomy; in view of concerns that providers of surgery may exploit vulnerable women, there is a growing call from professional bodies to improve education and counselling.23,24 Our study found that six times as many women who have had a vulvoplasty have had other cosmetic procedures as have other women, which suggests that they have a lower tolerance for perceived physical imperfections. A similar difference was reported by a small UK study, in which 10 of 55 women who had undergone vulvoplasty were also diagnosed with body dysmorphic disorder (compared with none of the control group of 70 women).22 The authors recommended further studies for exploring this relationship, and others have called for more psychological screening of women who request vulvoplasty.23,25

The quality of evidence in studies of women’s satisfaction after vulvoplasty has been criticised in terms of the follow-up and the measures employed.9 Most studies have been undertaken by the surgeons who performed vulvoplasties, reporting data based on questionnaires sent to their own patients.9,13 Impaired sexual function caused by scarring and nerve damage has been mentioned as a potential problem after genital surgery.9,23 Satisfaction and long term outcomes warrant further investigation, especially as the number of women having the procedure outside hospitals is unknown.

In our study, one in 14 procedures was associated with a serious short term adverse event or complication within 2 weeks of surgery. Urinary tract problems were the most common, but these are rarely mentioned in the literature; wound dehiscence has instead been reported as the most frequent short term adverse event.1 The serious complication rate in our study (7.2%) was slightly higher than reported by small, surgeon-led studies (2.7–6.0%).7 However, other studies have also included longer term complications (eg, dyspareunia and delayed local pain) that would not be recorded in the population data upon which we based our study. By analysing hospital data, we could only detect complications or adverse events sufficiently serious to warrant a diagnosis or hospital admission, so we may have underestimated the overall complication rate. Women who experienced more pain than they anticipated, were unhappy with the aesthetic results of the procedure, or felt dissatisfied in other ways would not be definitively captured. About one in 23 women had a repeat procedure, perhaps reflecting wound healing problems after being discharged from hospital, or longer term dissatisfaction with the results of the procedure.

The relationship between vulvoplasty and subsequent birth outcomes has not previously been explored. For vaginal births, perineal outcomes were similar for women with and without vulvoplasty, so that women who have had a vulvoplasty can be reassured about their prospects for a vaginal birth. However, the caesarean delivery rate was 30% higher for women who had had vulvoplasty; the increase was predominantly in pre-labour caesarean deliveries, suggesting a higher rate of planned birth interventions. Vulvoplasty may have influenced decisions about birth plans; surgeons or the women themselves may have been worried that a vaginal birth might disturb the results achieved by vulvoplasty.

As routine data about procedures performed outside hospitals are not available, the overall frequency of vulvoplasty in NSW could not be determined, and women who had vulvoplasties performed outside NSW (including overseas) were not captured by our study. Nevertheless, our investigation was the first population-based study of vulvoplasty. It thereby avoided sampling bias, and analysed routinely collected data to provide a snapshot of the current situation in NSW hospitals. Further, it provides information about serious complications that can be useful for pre-surgery counselling of women considering the procedure.

Box 1 –

Numbers of vulvoplasties performed in New South Wales private and public hospitals, 2001–2013

Box 2 –

Characteristics of 4381 women at their first record of vulvoplasty in New South Wales hospitals, 2001–2013, compared with a reference population of NSW women17–20

|

|

Women undergoing first vulvoplasty

|

Reference population of NSW women

|

|

|

Country of birth

|

|

|

|

Australia

|

3269 (74.6%)

|

67.6%

|

|

Elsewhere/unknown

|

1112 (25.4%)

|

32.4%

|

|

Previous cosmetic procedures

|

|

|

|

Any cosmetic procedure, including:

|

444 (10.1%)

|

1.7%

|

|

Breast augmentation

|

236 (5.4%)

|

0.9%

|

|

Liposuction

|

230 (5.3%)

|

0.8%

|

|

Face/brow lift

|

44 (1.0%)

|

0.2%

|

|

Age

|

|

|

|

15–24 years

|

1109 (25.3%)

|

23.1%

|

|

25–34 years

|

1427 (32.6%)

|

25.2%

|

|

35–44 years

|

1132 (25.8%)

|

26.3%

|

|

45–54 years

|

713 (16.3%)

|

25.5%

|

|

Marital status

|

|

|

|

Never married

|

1884 (43.0%)

|

33.1%

|

|

Married/de facto

|

1861 (42.5%)

|

55.4%

|

|

Widowed/divorced/separated

|

439 (10.0%)

|

11.6%

|

|

Unknown

|

197 (4.5%)

|

—

|

|

Smoking status

|

|

|

|

Smoker

|

691 (15.8%)

|

14.2%

|

|

Socio-economic status (SEIFA score quintile)

|

|

1 (most disadvantaged)

|

643 (14.7%)

|

20.0%

|

|

2

|

633 (14.5%)

|

20.0%

|

|

3

|

779 (17.8%)

|

20.0%

|

|

4

|

800 (18.3%)

|

20.0%

|

|

5 (least disadvantaged)

|

1363 (31.1%)

|

20.0%

|

|

Unknown (residence outside NSW)

|

163 (3.4%)

|

—

|

|

|

SEIFA = Socio-Economic Indexes for Areas. * Based on postcode of residence at time of the procedure.

|

Box 3 –

Characteristics of vulvoplasty procedures performed in New South Wales hospitals, 2001–2013

|

|

Vulvoplasty procedures, 2001–2013

|

|

|

Total number of procedures

|

4592

|

|

Hospital

|

|

|

Public: Sydney

|

638 (13.9%)

|

|

Private: Sydney

|

2729 (59.4%)

|

|

Public: outside Sydney

|

560 (12.2%)

|

|

Private: outside Sydney

|

665 (14.5%)

|

|

Hospital stay

|

|

|

Day only

|

3165 (68.9%)

|

|

1 night

|

748 (16.3%)

|

|

2 nights

|

299 (6.5%)

|

|

> 2 nights

|

380 (8.3%)

|

|

General anaesthesia

|

4363 (95.0%)

|

|

Any serious adverse event*

|

332 (7.2%)

|

|

Haemorrhage

|

82 (1.8%)

|

|

Infection

|

14 (0.3%)

|

|

Urinary tract

|

181 (3.9%)

|

|

Other†

|

73 (1.6%)

|

|

Re-admission within 2 weeks of procedure

|

121 (2.6%)

|

|

|

* Serious adverse event occurring during procedure admission or re-admission within 2 weeks (some women had more than one serious adverse event). † Includes disruption of operation wound and other complications.

|

Box 4 –

Birth outcomes for primiparous women in New South Wales, 2001–2012, according to vulvoplasty history

|

|

Women with previous vulvoplasty

|

Women without previous vulvoplasty

|

P*

|

|

Number

|

Percentage (95% CI)

|

Number

|

Percentage (95% CI)

|

|

|

Number of women

|

257

|

|

454 027

|

|

|

|

Hospital

|

|

|

|

|

0.33

|

|

Public

|

182

|

70.8% (65.0–76.0)

|

333 618

|

73.5% (73.3–73.6)

|

|

|

Private

|

75

|

29.2% (24.0–35.0)

|

120 409

|

26.5% (26.4–26.7)

|

|

|

Birth mode

|

|

|

|

|

< 0.001

|

|

Non-instrumental vaginal

|

118

|

45.9% (39.9–52.0)

|

225 042

|

49.6% (49.4–49.7)

|

|

|

Forceps

|

10

|

3.9% (2.1–7.0)

|

33 008

|

7.3% (7.2–7.3)

|

|

|

Vacuum

|

26

|

10.1% (7.0–14.4)

|

57 971

|

12.8% (12.7–12.9)

|

|

|

Intrapartum caesarean delivery

|

52

|

20.2% (15.8–25.6)

|

87 650

|

19.3% (19.2–19.4)

|

|

|

Pre-labour caesarean delivery

|

51

|

19.8% (15.4–25.1)

|

50 134

|

11.0% (10.9–11.1)

|

|

|

Missing data

|

0

|

0

|

222

|

< 0.05%

|

|

|

Episiotomy (vaginal births)†

|

|

|

|

|

0.20

|

|

Yes

|

37

|

24.0% (18.0–31.4)

|

90 550

|

28.7% (28.5–28.8)

|

|

|

No

|

117

|

76.0% (69.6–82.0)

|

225 471

|

71.3% (71.2–71.5)

|

|

|

Perineal spontaneous tearing (vaginal births)†

|

|

|

|

|

0.87

|

|

Intact/first degree tear

|

66

|

42.9% (35.3–50.8)

|

118 028

|

37.3% (37.2–37.5)

|

|

|

Second degree tear

|

46

|

29.9% (23.2–37.5)

|

90 690

|

28.7% (28.5–28.9)

|

|

|

Third/fourth degree tear

|

5

|

3.2% (1.4–7.4)

|

12 681

|

4.0% (3.9–4.1)

|

|

|

Other

|

30

|

19.5% (14.7–27.6)

|

58 042

|

18.4% (18.2–18.5)

|

|

|

|

* χ2 test. † Numbers do not sum to 100% as episiotomy and perineal tearing categories were not mutually exclusive until 2007.

|

more_vert

more_vert