Intentional poisoning is a major public health problem and generally occurs in the context of deliberate self-harm and drug misuse. There are 60 International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems, 10th revision (ICD-10) codes for drug-related deaths. In 2009, these codes together accounted for 6.4% of male and 5.5% of female total years of potential life lost in Australia.1 Most deaths are in young people, and drug-related deaths account for a large proportion of lost years of life — causing about 25% of completed suicides.1 The estimated Australian rate of people hospitalised for self-poisoning of 119 per 100 000 population per year2 substantially underestimates total numbers as many patients are not admitted or do not present.3 Most poisonings are in young adults and are impulsive or unplanned. Morbidity and mortality from poisoning has proved surprisingly responsive to targeted public health interventions to reduce the availability of means to poison oneself accidently or deliberately.4,5 Identification of drugs causing disproportionate numbers of poisonings, morbidity or deaths is thus a key aspect of an effective toxicovigilance system.

We aimed to examine inhospital morbidity and mortality associated with poisoning in the greater Newcastle region over 26 years and to broadly determine what factors have (and have not) changed over this time, during which there have been substantial changes in medication use. In particular, the use of psychotropic drugs has changed and there have been large increases in antidepressant prescribing in Australia over the past three decades.6,7 Favourable and unfavourable effects on population suicide rates have been postulated for antidepressants.8,9 Thus we assessed the effect of the increase in antidepressant prescribing on total and antidepressant self-poisoning, and examined changes in prescribing of and self-poisoning with several drugs that have previously been identified as having higher relative toxicity in overdose: short-acting barbiturates, dextropropoxyphene, chloral hydrate, dothiepin, thioridazine, pheniramine, temazepam, amisulpride, alprazolam, venlafaxine and citalopram.10–15

Methods

This is a cohort study of patients presenting consecutively after self-poisoning to the Hunter Area Toxicology Service (HATS) between January 1987 and December 2012. Since 1987, HATS has provided a comprehensive 24 hours/day toxicology treatment service for a population of about 500 000. From 1992, ambulances diverted all poisoning presentations in the lower Hunter to this service. HATS currently has direct clinical responsibility for all poisoned adult patients in all hospitals in the greater Newcastle region and provides a tertiary referral service to Maitland and the Hunter Valley. HATS routinely records data on patients who present to hospital (even if the poisoning is uncomplicated).16 Previous studies on poisoning in Newcastle17,18 have shown that no patients were treated exclusively in private hospitals or by their family doctor, indicating that most presentations to medical care facilities are recorded. This cohort does not comprehensively cover unintentional childhood (age < 14 years) poisonings. The local human research ethics committee has previously granted an exemption regarding use of the database and patient information for research.

A structured data collection form is used by HATS to prospectively capture information on patient demographics (age, sex, postcode), drugs ingested (including doses), co-ingested substances, regular medications and management and complications of poisoning.19 At discharge, further information is collected (eg, hospital length of stay [LOS], psychiatric and substance misuse diagnoses). Data are routinely entered into a fully relational Microsoft Access database separate to the hospital’s main medical record system. Data on all patients aged ≥ 14 years who presented following self-poisoning were analysed.

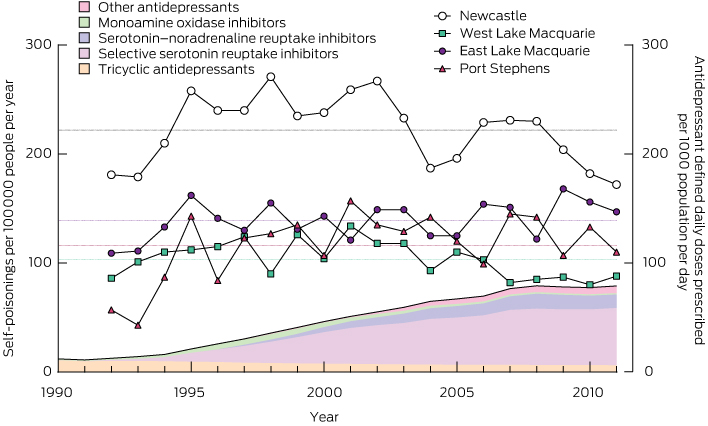

Analyses of population-referenced data (ie, rates) were restricted to postcodes that predominantly cover Newcastle, Lake Macquarie and Port Stephens. Changes in total self-poisoning rates in the four statistical subdivisions in this area were examined between 1991 and 2011. Changes in rates of self-poisoning using the main antidepressant drug classes (tricyclic antidepressants [TCAs], selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors [SSRIs], serotonin–noradrenaline reuptake inhibitors [SNRIs], monoamine oxidase inhibitors [MAOIs] and other) were also examined. Data on rates of antidepressant drug use in these drug classes (standardised by the defined daily dose [DDD]) in Australia from 1991 to 2011 were taken from Australian government publications. We have previously shown that these data agreed within two significant digits with Newcastle-specific data for a range of medications.11

Results

Over the study period, there were 17 266 admissions of patients who had self-poisoned and 11 049 individual patients; the median number of admissions per patient was one (range, 1–115). The number of admissions increased over the first 8 years, but since 1995 has been quite stable (HATS became well established in 1994) (Appendix 1).

Of the total admissions, 15 327 (88.8%) were attempts at self-harm and the remainder were a mixture of unintentional, iatrogenic and recreational self-poisonings. (Data are generally presented for admissions, and may thus include the same patient with different poisonings.) The median age of admitted patients was 32 years (range, 14–97 years) and the female : male ratio was 1.6 : 1 (10 514 female, 6711 male and 39 transgender patient admissions). The median LOS was 16 hours (interquartile range, 9.3–25.7 hours; total time spent in hospital, 15 688 hours). Of the total admissions, 2101 involved admission of the patient to an intensive care unit (ICU) (12.2%) and 1281 involved ventilation of the patient (7.4%). There were 78 inpatient deaths (0.45% of admissions).

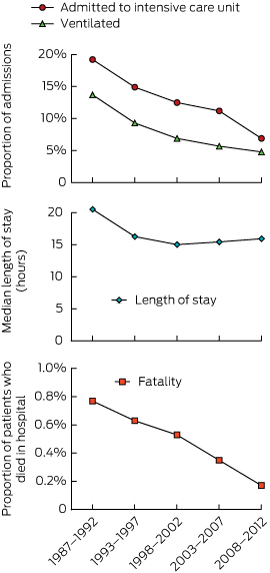

We investigated the changes in morbidity and mortality over the study period by dividing admissions into those in the first 6 years, reported previously,20 and four subsequent 5-year periods (Box 1). Over this period, the rate of admission to ICU dropped from 19.2% (376/1955) to 6.9% (280/4060) and rate of mechanical ventilation from 13.7% (268/1955) to 4.8% (193/4060). The fatality rate dropped from 0.77% (15/1955) to 0.17% (7/4060). The median LOS decreased from 20.5 hours in the first 6 years to about 16 hours in all subsequent 5-year periods.

In the 17 266 admissions, a previous history of psychiatric illness (9692, 56.1%), previous admission for a psychiatric episode (6426, 37.2%), previous suicide attempt (9665, 56.0%) and history of alcohol or drug misuse (8466, 49.0%) were commonly recorded. Few admitted patients were in full-time paid work (2421, 14.0%); some were unemployed (3622, 21.0%), pensioners or retired (4163, 24.1%), students (1058, 6.1%), doing home duties (920, 5.3%) or other (703, 4.1%); data were missing for the remainder (4379, 25.4%). Only 23.8% (4104) were married; others were single (9567, 55.4%), separated (1325, 7.7%), divorced (1302, 7.5%), widowed (409, 2.4%), in de facto relationships (79, 0.5%), other (13, 0.1%); and data were missing for the remainder (467, 2.7%). These demographic, social and psychiatric factors remained stable, except for a slight rise in the proportion of patients reporting previous self-harm (Appendix 2).

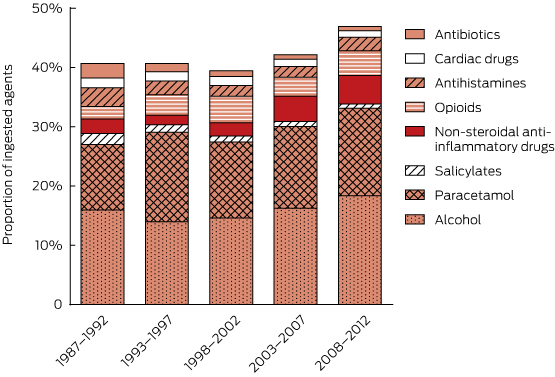

Including co-ingested alcohol, 34 342 substances were involved (mean, 1.99 per patient; range, 1–18 per patient). The major groups of agents involved in self-poisonings and ICU admissions are shown in Appendix 3 (drugs usually available on prescription) and Appendix 4 (non-prescription drugs and other substances). The most commonly ingested substances were benzodiazepines (5470, 15.9%), alcohol (5461, 15.9%), paracetamol (4619, 13.5%), antidepressants (4477, 13.0%), antipsychotics (3180, 9.3%), anticonvulsants (1514, 4.4%), opioids (1232, 3.6%), non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (1104, 3.2%) and antihistamines (743, 2.2%). Prescription items accounted for 18 950 agents (55.2%), of which 14 445 (76.2%) were known to have been prescribed for the patient.

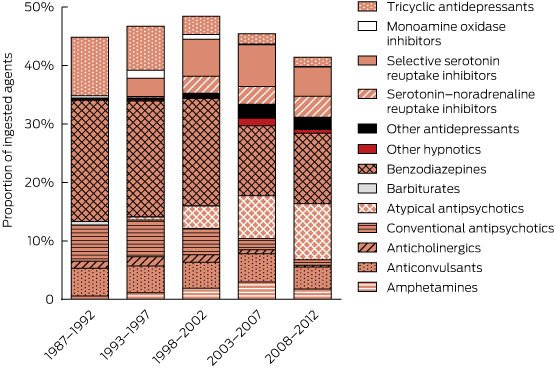

There were major changes over time in the patterns of drugs ingested (Box 2, Box 3), especially for psychotropic drugs and sedatives. Psychotropic drugs consistently accounted for about 50% of all drugs ingested but newer antidepressants and atypical antipsychotics have largely replaced the older drugs (TCAs and conventional antipsychotics). Several of the drug classes for which frequency of ingestion declined (eg, barbiturates, theophylline, TCAs) have disproportionately high toxicity (Appendix 3). In some drug classes, there were larger declines in individual drugs identified as having greater toxicity in the mid 1990s10–13 (Appendix 5). This is only partly explained by falling prescriptions for these agents (Appendix 6).

There was a more than sixfold increase in antidepressant DDDs per 1000 people per day between 1991 and 2010 (from 12 to 77). However, the increase in the proportion of poisonings due to antidepressants was very modest (about 1.34-fold). There were no corresponding changes in the population rates of self-poisoning (Box 4, Appendix 6), which fluctuated around the long-term mean in each district. There was thus a large decrease in the rate of self-poisoning per DDD prescribed per 1000 population per day for antidepressants (Appendix 7). In Box 4, the increase in total antidepressant prescriptions is illustrated by the total shaded area and changes in individual classes are illustrated by the coloured shading.

Discussion

The rates of self-poisonings in Newcastle were stable over the past two decades, and the features of the population presenting with self-poisoning were constant. This suggests a long-term ongoing and reasonably predictable need for clinical toxicology treatment and ancillary psychiatric and drug and alcohol support services. Despite large increases in prescriptions for drugs used to treat psychiatric illness (and a range of other major mental health interventions), there appears to have been no positive result in terms of reducing episodes of self-harm.

Interestingly, there was a more than sixfold increase in the use of antidepressants, and while the agents taken in overdose changed substantially, there were only small changes in rates of antidepressant overdoses. Interpreting this surprising finding is not straightforward. It probably indicates that antidepressants are increasingly being prescribed for patients who have minimal risk of self-harm. Reassuringly, there is no evidence in our population to support concerns about pro-suicidal effects of new antidepressant prescriptions. The lack of any change in overall self-harm rates also suggests that increased antidepressant use for depression is not an effective public health strategy to reduce rates of self-harm. The only strategy to prevent fatal poisoning with consistent supporting evidence is restricting the availability of high-lethality methods.4,5

Identification of high toxicity in overdose is a problem that can only be studied after approval for marketing is granted. Postmarketing surveillance by pharmaceutical companies of toxicity in overdose is not a requirement for drug registration in Australia or any other country. There is little incentive for voluntary surveillance. Although most companies record case reports of overdoses of their drugs, this does not facilitate comparisons. Reporting biases mean that such cases may be atypical of the usual clinical picture.

The many new psychiatric medications coming onto the market should mandate coordinated collection of timely information on self-poisoning and suicide. Ideally, this should be done at three levels. First, a national coronial register of drug-related deaths is essential to enable an analysis of relative mortality (as done in the United Kingdom21). Second, data on poisonings reported to poison centres are essential, particularly for childhood poisonings that rarely require admission and for assessing the effect of primary prevention measures. Poison centre data have limitations due to referral bias, lack of uniformity of assessment and lack of clinical information.22 Third, for these reasons, systematic use of clinical databases to record hospital admissions for cases of poisoning is needed to measure relative clinical toxicity.

The HATS clinical database has identified disproportionate effects in overdoses with many drugs. Translation of HATS data into clinical risk assessment and guidelines has occurred, but with lengthy delays. For example, the risk of QT prolongation and torsades de pointes with thioridazine, citalopram and escitalopram10,14,23 were detected in the database 5–10 years after these drugs became available. However, to reduce the time to identify toxicological problems to 1–2 years, collaborating centres in Australia and overseas will be needed to accelerate collection of data on self-poisoning.

Most deaths due to poisoning occur outside hospital. Any significant decrease in mortality from self-poisoning will result from primary or secondary prevention. Efforts at decreasing morbidity and mortality from self-poisoning should continue to target drugs that are frequently taken or are lethal in overdose.

The falls in prescriptions and poisonings with several drugs with greater relative toxicity occurred several years after the problems relating to overdoses with these drugs were identified in the HATS database around 1994–1995 (Appendix 6, Appendix 8). For example, large reductions were due to withdrawal of drug subsidies (those for dextropropoxyphene and thioridazine were withdrawn in 2000) and removal of a formulation that was misused (temazepam gel-filled capsules were withdrawn in 2001). Publication of toxicity data alone had limited (if any) effect in terms of reducing prescriptions of the more toxic drugs. No drugs were banned in Australia on the basis of HATS data, although manufacturers did voluntarily withdraw some of the highlighted drugs (barbiturates and chloral hydrate were withdrawn in 1994–1995, thioridazine was withdrawn in 2009). Further, there has been no drop yet in prescriptions of or poisoning with drugs identified as having greater toxicity in the mid 2000s14,15 (data not shown).

Our data show large drops in rates of poisoning with some of the more lethal drugs, such as TCAs and barbiturates (Box 2, Box 4). The introduction of less toxic antidepressants and sedatives dramatically changed prescribing, which in turn changed the types of drugs taken in self-poisoning. This trend has presumably also been reflected in changes in drug-related deaths. However, the nature of coding in official death statistics means that there are no published Australian data to support this contention. For example, poisoning by “antiepileptic, sedative-hypnotic, antiparkinsonism and psychotropic drugs” are all lumped together under one code in Australia.1 Most fatal poisonings are classified as due to unspecified or multiple agents. Some improvement in coding of drug-related deaths should not be difficult. Much finer detail is provided in other ICD-10 codes. For example, the Australian Bureau of Statistics records deaths from crocodile and rat bites (three and zero, respectively, between 1999 and 2008) separately from those caused by other animal bites.1 The development of the National Coronial Information System, launched in 2000, may make fatal poisoning comparisons possible in future, but only if data are accurately and consistently coded. Assessing the impact that clinical toxicology has on direct patient management and on public health is hindered by the lack of reliable epidemiological and clinical data.

Our data have inherent limitations. There is likely to be selection bias against less severe poisonings (the types of cases where patients might not present for medical attention) and rapidly lethal poisonings (cases in which patients die outside hospital). In surveys of self-harm and anecdotal reports from patients, it has been estimated that a significant proportion of people who have self-poisoned (5%–15%) don’t present for medical care.3 Also, although there is a prospective data collection form, retrospective review of medical records is often required to complement prospectively collected data. Data on the ingested drugs were based on patient history, including corroborating history obtained from ambulance officers and accompanying people and from information on drug containers. Drug concentrations were not measured in most patients, although previous research on specific drugs has found the patient history of drugs ingested to generally be confirmed by an appropriate assay.24

The key strengths of our study are its long duration and the consistent core data fields. There are few similar attempts to gather data longitudinally on self-poisoning over prolonged periods. Many have retrospective identification of cases from hospital coding and thus rely entirely on the completeness of medical records.25 Others have not been collected continuously26 or have focused on psychiatric factors and treatment (rather than drugs ingested and toxicity)27 or were conducted in developing countries where agents ingested differ substantially from those used in Australia.28

However, the uniqueness of the HATS database also highlights a weakness of our study. As there are no comparable current datasets, it is difficult to determine the extent to which the Hunter experience represents that of the developed world. Expansion of the database could be facilitated by database systems integrated with electronic medical records.

We identified interesting and important patterns relating to drug prescriptions, epidemiology of overdose patients and importance of relative toxicity. A massive increase in antidepressant prescriptions has had little impact on rates of self-harm or antidepressant poisoning. Changes in antidepressant classes (generally from more to less toxic) have had significant effects on morbidity and mortality from antidepressant poisoning, and therefore from all poisonings. We were also able to generate information regarding relative toxicity and patient management. However, for many rare poisons, gaining sufficient numbers of patients to generate reliable information about management and prognosis will take decades from one centre. We believe that, in Australia and overseas, there is a need for a coordinated approach to address the toxicity of drugs in overdose. The public health benefits would greatly outweigh the modest costs of enhancing postmarketing surveillance through more widespread systematic collection of poisoning and overdose data.

1 Morbidity and mortality due to self-poisoning, 1987–2012, measured by need for intensive care and ventilation, length of stay and fatality*

2 Use of sedatives and psychotropic drug classes in self-poisoning, 1987–2012

3 Use of alcohol, analgesics and selected other drug classes in self-poisoning, 1987–2012

4 Rates of antidepressant prescribing (1990–2011, shaded areas) and total rates of self-poisoning (1992–2011, solid lines and symbols)*

more_vert

more_vert