The increasing incidence of sepsis is well recognised, and is generally attributed to the growing prevalence of chronic conditions in ageing populations.1–3 In New South Wales, the number of patients with a diagnosis of sepsis in the Admitted Patient Data Collection (APDC) has increased, and sepsis was involved in 17.5% of in-hospital deaths in 2009, compared with a mortality of 1.5% for all hospital separations (unpublished data).

The clinical presentation of sepsis may be subtle; fever is not always present.4,5 In NSW, failure to recognise and respond to sepsis has been regularly reported. In 2009, 167 incidents were highlighted in a clinical focus report published by the Clinical Excellence Commission (CEC).6 A Quality Systems Assessment in 2011, completed by over 1500 respondents across the NSW hospital system, reported that 34% of clinical units did not have guidelines or protocols for managing sepsis.7

This article reports on the SEPSIS KILLS program of the CEC, which aims to promote the skills and knowledge needed for recognising and managing patients with sepsis in NSW hospital emergency departments.

Methods

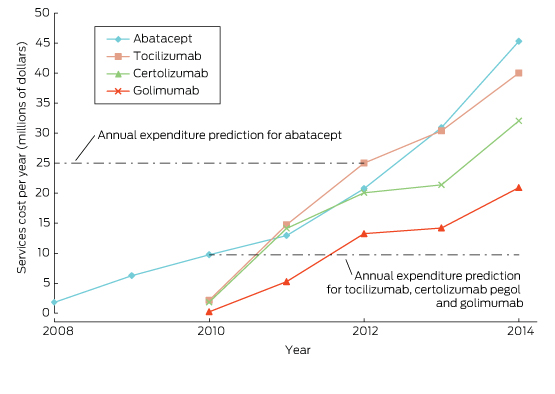

The focus of the program is to RECOGNISE risk factors, signs and symptoms of sepsis; RESUSCITATE with rapid intravenous fluids and antibiotics; and REFER to senior clinicians and teams. Standardised sepsis tools were developed in consultation with NSW emergency physicians, and included adult and paediatric pathways that built on the NSW deteriorating patient system, Between the Flags (BTF).8 The vital signs assessed in the sepsis pathways were consistent with BTF, and varied marginally from accepted systemic inflammatory response criteria (Box 1).

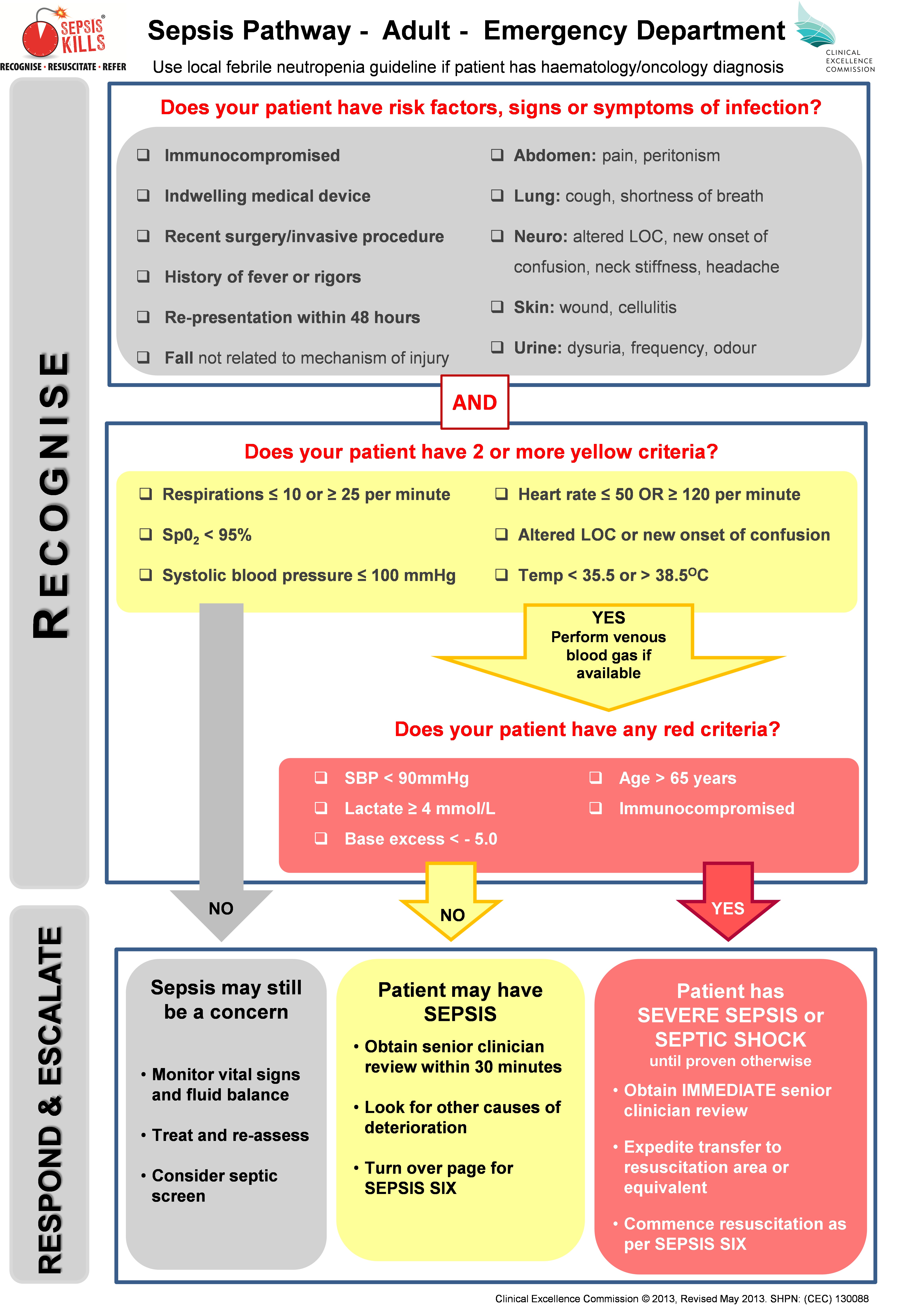

The SEPSIS KILLS pathways promote bundles of care, with the emphasis on early intervention. The adult bundle includes taking blood cultures, measuring serum lactate levels, administering intravenous antibiotics within an hour of triage and recognition, and administering a fluid bolus of 20 mL/kg, followed by another bolus of 20 mL/kg (if necessary) and inotropic drugs if the patient’s condition is not fluid-responsive. If no improvement is observed, senior medical review and admission to intensive care or retrieval to a major centre should be considered (Box 2). The paediatric bundle emphasises the importance of early senior clinical review and decision making. In addition, an empiric antibiotic guideline was developed with advice from expert infectious disease physicians. Emphasis was placed on the first dose of antibiotics, thereby allowing time for further assessment and diagnosis. Because of wide variations in practice, the guideline also contained details on how antibiotics could be administered most expeditiously.

The program was implemented in 2011 with a top-down, bottom-up approach, with strong leadership from medical and nursing clinical leads, and supported by the local health district Clinical Governance Units. Participation was not mandatory, and no extra resources were provided to participating emergency departments who implemented the program. The CEC team supported clinicians by holding a preliminary launch, monthly CEC–hospital teleconferences, executive reports, newsletters, site visits and workshops. A range of online resources was provided, including a Sepsis Toolkit (implementation guide) and various education tools.

Emergency departments were encouraged to collect prospective data on paediatric and adult patients with a provisional diagnosis of sepsis who had received intravenous antibiotics. An online sepsis database (from August 2011) facilitated collection of a minimum dataset for each patient that included their date of birth, triage time and date, triage category, clinical observations (including systolic blood pressure [SBP] and serum lactate levels), time and date of initial intravenous antibiotic treatment and of commencement of the second litre of intravenous fluid, the presumptive source of sepsis, and the disposition of patients following emergency department treatment. Data were collected either prospectively or by retrospective chart review. The database allowed emergency departments to monitor time to antibiotics and fluids in real time, and to compare this with the corresponding local health district and NSW data.

Ethics approval was obtained from the NSW Sepsis Register, which was developed as a public health and disease register under s98 of the Public Health Act 2011. The Sepsis Register is maintained by the CEC.

Data analysis

Analysis of process measures (time to antibiotic, time to intravenous fluid) was based on data from the SEPSIS KILLS database. A total of 13 567 SEPSIS KILLS records were submitted for linkage to the APDC to assess associations between in-hospital mortality and sepsis severity and patient disposition. Patients were classified by emergency department staff according to the Australasian Triage Scale (ATS).9 The cases were further classified as being severe or uncomplicated sepsis according to the serum lactate levels and presenting SBP of the patient.

To assess the population-level impact of the SEPSIS KILLS program, we analysed health outcomes (in-hospital mortality, hours in intensive care, length of stay) for paediatric and adult patients separated from NSW hospitals with ICD-10-AM (International Classification of Diseases, 10th revision, Australian modification) discharge diagnosis codes consistent with sepsis10 recorded in the Admitted Patient, Emergency Department Attendance and Deaths Register. This register was accessed through the NSW Ministry of Health Secure Analytics for Population Health Research and Intelligence (SAPHaRI) system. Linkage was undertaken by the Centre for Health Record Linkage (CHeReL). Only patients admitted to public hospitals with emergency departments were included in the analysis. Trend analysis was performed for the run-in period, August 2009 – December 2011, and for the two following years, 2012 and 2013. Outcomes by sepsis severity could not be analysed at the population level because of the lack of consensus about using ICD-10-AM codes to differentiate between severe and uncomplicated sepsis.

Descriptive and inferential analyses included the calculation of frequencies, odds ratios (ORs) and 95% confidence intervals, and χ2 tests for trends. Trends over time for process and outcome measures were assessed in regression models. Logistic regression was used to analyse in-hospital deaths, while linear regression models were used for time in intensive care and lengths of stay. Models were adjusted as appropriate for covariates (age, year, triage category and severity of sepsis). Statistical significance was defined as P < 0.05.

Results

The SEPSIS KILLS program was implemented as individual emergency departments became ready during 2011. Both retrospective and prospective data were collected by 97 hospitals to 31 December 2013 and entered into the sepsis database. Data were submitted by 13 tertiary, 19 metropolitan and 65 rural hospitals. Because of the low number of paediatric patients, analysis was restricted to data for adult patients.

The provisional sources of sepsis included the lungs (5216 patients, 40.5%), urinary tract (2998, 23.2%), abdomen (1077, 8.4%), skin or soft tissue (975, 7.6%), musculoskeletal system (98, 0.8%), central nervous system (96, 0.7%), vascular device (82, 0.6%), and other systems (973, 7.6%). For 1238 patients (9.6%) the source was unidentified, for 133 (1.0%) no source was recorded.

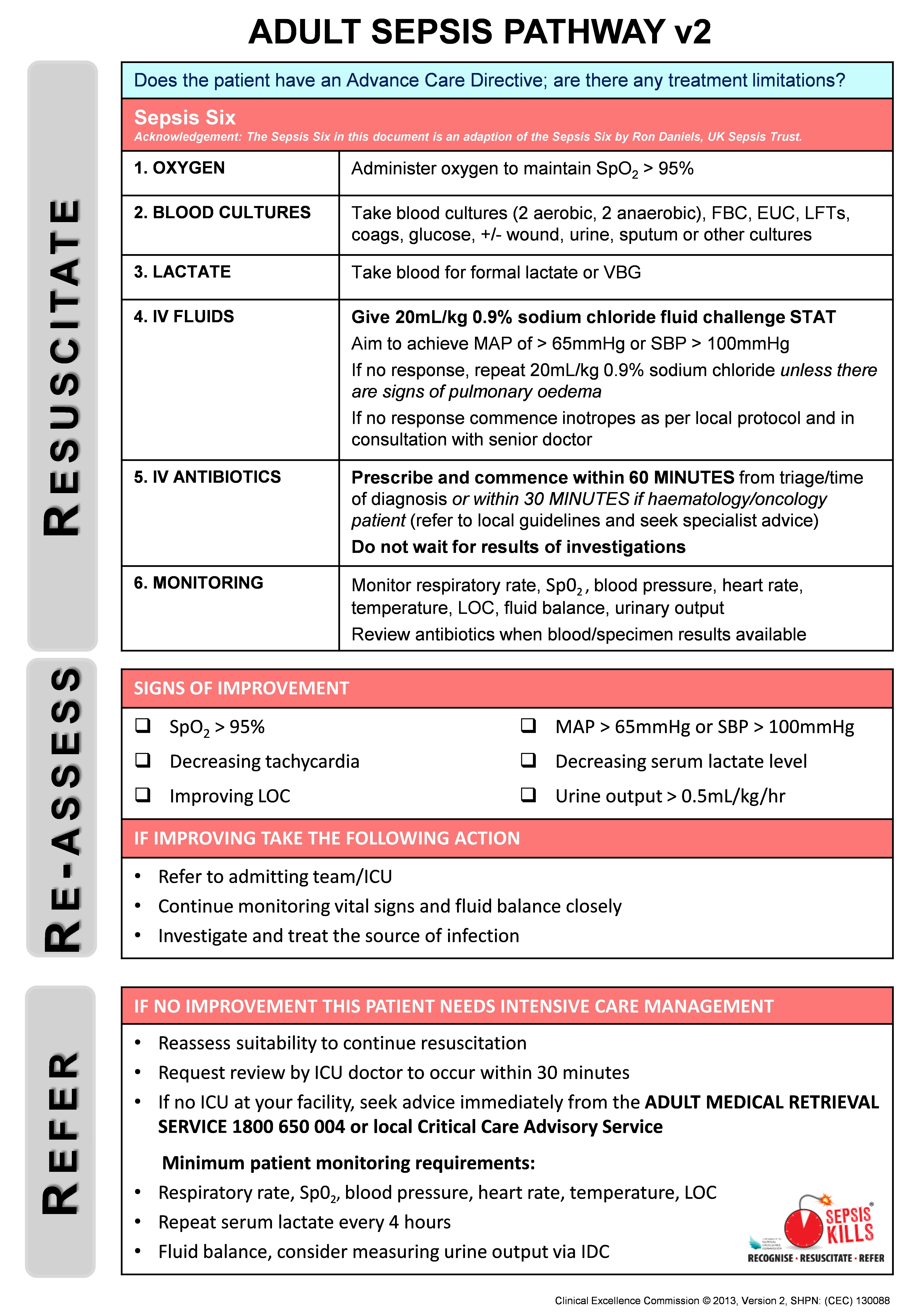

There were age data in 12 879 records. There was a significant reduction in the mean age of patients between 2009 and 2013, from 67.3 years in 2009–2011 to 64.8 years in 2013 (P < 0.001 for trend; Box 3).

Data for the process indicators from the CEC sepsis database are summarised in Box 3. The proportion of patients who were categorised at triage as ATS 1 (“see immediately”) rose from 2.3% in 2009–2011 to 4.2% in 2013. Those categorised as ATS 2 (“see within 10 minutes”) increased from 40.7% in 2009–2011 to 60.7% in 2013 (P < 0.001). There were small reductions in the proportions of patients classed as ATS 3, 4 or 5.

The proportion of patients who received antibiotics within 60 minutes of triage or recognition increased from 29.3% in 2009–2011 to 52.2% in 2013 (linear trend test, P < 0.001). Similarly, the number of patients who started a second litre of intravenous fluid within one hour rose from 10.6% to 27.5% (linear trend test, P < 0.001).

The analysis of population-based APDC data, which included all separations with emergency department involvement from public hospitals in NSW between January 2009 and December 2013, is presented in Box 4. There were 15 801 sepsis hospital separations during the run-in period of 2009–2011, with a mortality of 19.3%. This rate declined to 17.2% in 2012 and 14.1% in 2013. There was a significant linear decrease over time (P < 0.0001); the OR for death (compared with the run-in period) was 0.87 (95% CI, 0.80–0.94) in 2012, and 0.69 (95% CI, 0.63–0.74) in 2013. Significant linear declines were also observed for time in intensive care and length of stay (for each trend: P < 0.0001).

Linkage of the APDC and sepsis databases showed that the mortality rate for the 1616 patients with severe sepsis (serum lactate ≥ 4 mmol/L or SBP < 90 mmHg) was 19.7%; these patients were significantly more likely to die than patients with uncomplicated sepsis (serum lactate < 4 mmol/L and SBP ≥ 90 mmHg) (OR, 3.7; 95% CI, 3.2–4.4; P < 0.0001). The mortality rate for the 893 patients with hyperlactataemia (a lactate level of 4 mmol/L or more; reference interval, 0.5–2.0 mmol/L) was 24.9%, while that for 637 patients presenting with cryptic shock — hyperlactataemia together with normotension (SBP ≥ 90 mmHg) — was 21.2%. There was no change in mortality for either group over time. For 734 patients who presented with SBP < 90 mmHg and lactate levels < 4 mmol/L, mortality was 13.5%, which declined significantly across the study period (2009–2011, 16.5%; 2012, 16.0%; 2013, 9.8; P = 0.03). The overall mortality rate for uncomplicated sepsis patients increased significantly over time: 3.7% (21/567) in 2009–2011, 6.2% (145/2336) in 2012, and 6.7% (145/2164) in 2013 (P = 0.02).

The mortality rate for the 268 ATS 1 patients was 28.8%. The risk of death for patients over 65 years of age was 3.3 times higher (95% CI, 2.6–4.1) than for patients under 65 years of age (P = 0.001).

The mortality rate for 543 severe sepsis patients admitted to intensive care did not change significantly over time — 23.4% (2009–2011), 19.5% (2012) and 16.0% (2013) (P = 0.145) — nor did the proportion of the 1073 patients with severe sepsis who were admitted to the ward and died — 21.4% (2009–2011), 21.5% (2012) and 18.4% (2013) (P = 0.263). In contrast, the risk of death for 4225 patients with uncomplicated sepsis admitted to the ward increased significantly: 3.2% (15/466) during 2009–2011, 6.0% (115/1914) during 2012, and 6.2% (115/1845) during 2013 (P = 0.047).

Discussion

SEPSIS KILLS is a quality improvement program that aims to reduce preventable harm to patients with sepsis by recognising the condition early and managing it promptly. It is based on the principle that early recognition and aggressive management with antibiotics and fluids will improve outcomes.11–13 It is consistent with the 3-hour component of the resuscitation bundle outlined in the international guidelines of the Surviving Sepsis Campaign.3

The program was not planned as a before-and-after project, but was independently implemented by individual emergency departments during 2011. More than 80% of NSW emergency departments (175 of 220) used the sepsis pathways, and 97 emergency departments submitted over 13 000 records. The resulting increase in the number of patients for whom antibiotics were initiated within 60 minutes of recognition and the increased likelihood of the second litre of fluids being started in the first hour indicate that the program was successful. Greater urgency is also apparent from the marked increase in the number of patients classified at triage as ATS 2. We cannot, however, explain the significant age difference between the patients seen in 2012 and 2013.

Reviewing the population-based APDC hospitalisations with an ICD-10-AM code for sepsis showed that there was a steady reduction in mortality over time. Contrary to what we expected, the survival benefit in our patients appears to have been greatest for those with evidence of haemodynamic instability (SBP < 90 mmHg) but normal lactate levels.

The mortality rate of 15%–20% for patients admitted to intensive care with severe sepsis (one-third of the overall sample) is consistent with the overall mortality rate in Australian and New Zealand intensive care units.14,15 In 2013, the crude mortality rate for the patients admitted to wards was higher than that for the intensive care group. We believe the relatively high proportion of ward patients may be the result of an underappreciation of the potential mortality of sepsis, of the significance of elevated lactate levels, and of the time course of the septic process, as well as of failure to recognise cryptic shock16 and the obvious and practical problem of intensive care unit bed availability. We did not assess how many had end-of-life treatment limitations in place.

Managing large numbers of patients with sepsis on the wards has been described elsewhere.17,18 These patients have not been well studied, although a number of studies have identified deficiencies in care.19–21 The significant increase in mortality among patients with uncomplicated sepsis admitted to the ward causes concerns that some of our ward patients may have qualified for intensive therapy. An increase in mortality in less severe sepsis has also been documented by other authors.22

The major challenge was managing the prescribing of antibiotics. Despite general acceptance of expert guidelines for prescribing antibiotics, differences in their prescription and administration were observed. This evidence–practice gap is well recognised,23 and the empiric antibiotic guideline was developed to promote appropriate antibiotic prescribing practices and optimal outcomes.24 The empiric guideline was consistent with the principles of antimicrobial stewardship, and, while each site was allowed to modify it according to local opinion and antibiotic resistance patterns, changes were infrequent. Particular anxieties were expressed about prescribing and administering gentamicin. The administration component of the guideline was developed to promote the most expeditious method of administration rather than favouring the slow infusion that had become normal practice. Despite the emphasis on the first dose and timely review, antibiotics were often continued long after they should have been reviewed, following consideration of the results of pathology investigations.

Other challenges beyond our control included educating a high turnover workforce in emergency departments, as well as medical engagement, particularly in rural facilities where governance is difficult and there is no doctor on site, or locum medical staff are more common. There were wide variations in the methods of blood culture collection, and a standardised guideline for blood cultures was subsequently added to the Sepsis Toolkit.

Limitations

This work is subject to the limitations of any quality improvement project at multiple sites. The prolonged run-in period was not ideal. Our approach was not to measure compliance with the care bundle, as undertaken elsewhere, but to use time as a measure for promoting behavioural change among emergency department clinicians. Assessing patient outcomes was the major difficulty. The voluntary nature of data collection resulted in its inconsistent submission, and the lack of strict diagnostic criteria for sepsis resulted in patients with conditions from across the inflammatory condition–sepsis spectrum being included in the SEPSIS KILLS database. Resource limitations also meant that some sites implemented the pathways but did not submit data.

Reviewing the outcomes of patients with an ICD-10-AM code for sepsis in the population-based administrative APDC is an accepted approach. This, however, entails the risk of reviewing the outcomes of a different group of patients, a group for whom the final diagnosis might not be directly related to sepsis or its severity. This is a potential problem when comparing the final diagnosis in the APDC database with the provisional diagnosis in the SEPSIS KILLS data.

Finally, the improved outcomes described in our article may be the result of the SEPSIS KILLS program, but may also be related to other initiatives for improving quality of care.

Implications for clinicians, researchers and policy makers

The observation that patients with severe sepsis are being managed on the wards highlights the need for a shift in the focus of both practice improvement and research from intensive care to ward management. It also raises the problem of sepsis and the deteriorating patient. We informally estimated that around 30% of patients who required a Rapid Response call had sepsis, but this may be an underestimate, with rates possibly as high as 50%–60%.25 Finally, our work confirms the need for continued research into risk stratification tools for sepsis in the emergency department. In the meantime, all patients with lactate levels of 4 mmol/L or greater require intensive care unit review and admission.

The SEPSIS KILLS program promotes early recognition and management of sepsis during the first few hours in NSW emergency departments. By focusing on the principle of “Recognise, Resuscitate, Refer” it is possible to reduce the time before antibiotics are administered and fluid resuscitation initiated. This program could be applied in other jurisdictions and its integration with antimicrobial stewardship requirements should be considered.

Box 1 –

The SEPSIS KILLS pathway for adult patients in hospital emergency departments, page 1

Box 2 –

The SEPSIS KILLS pathway for adult patients in hospital emergency departments, page 2

Box 3 –

Characteristics, and process and outcome indicators of sepsis-related hospital separations before and after the launch of the SEPSIS KILLS program

|

Characteristics

|

Run-in period

|

SEPSIS KILLS program in operation

|

P for trend

|

|

Aug 2009 – Dec 2011

|

2012

|

2013

|

|

|

Number of separations

|

1585

|

5396

|

5905

|

|

|

Mean age ± SEM, years

|

67.3 ± 0.5

|

67.6 ± 0.3

|

64.8 ± 0.3

|

< 0.001

|

|

Triage category*

|

|

|

|

< 0.001

|

|

1

|

37 (2.3%)

|

176 (3.3%)

|

242 (4.2%)

|

|

|

2

|

463 (40.7%)

|

2765 (51.5%)

|

3532 (60.7%)

|

|

|

3

|

683 (43.2%)

|

2034 (37.9%)

|

1767 (30.4%)

|

|

|

4

|

207 (13.1%)

|

378 (7.0%)

|

267 (4.6%)

|

|

|

5

|

10 (0.6%)

|

16 (0.3%)

|

12 (0.2%)

|

|

|

Missing data

|

5

|

22

|

83

|

|

|

Antibiotic received within 60 min

|

464 (29.3%)

|

2165 (40.2%)

|

3083 (52.2%)

|

< 0.001

|

|

Second litre of intravenous fluid within 60 min

|

135 of 1272 patients (10.6%)

|

521 of 3631 patients (14.3%)

|

991 of 3609 patients (27.5%)

|

< 0.001

|

|

|

SEM = standard error of the mean.

|

Box 4 –

Hospital outcomes prior to and after the launch of the SEPSIS KILLS program, NSW, January 2009 to December 2013

|

Outcomes

|

Descriptive statistics

|

Odds ratio (95% CI)

|

P for trend

|

|

|

Deaths, numbers (percentage)

|

|

|

< 0.0001

|

|

2009–2011

|

3053/15 801 (19.3%)

|

1

|

|

|

2012

|

979/5683 (17.2%)

|

0.87 (0.80–0.94)

|

|

|

2013

|

870/6167 (14.1%)

|

0.69 (0.63–0.74)

|

|

|

Mean time in intensive care (SEM), hours

|

|

|

< 0.0001

|

|

2009–2011

|

32.7 (1.0)

|

|

|

|

2012

|

26.6 (1.4)

|

|

|

|

2013

|

25.8 (1.3)

|

|

|

|

Mean length of stay (SEM), days

|

|

|

< 0.0001

|

|

2009–2011

|

13.5 (0.1)

|

|

|

|

2012

|

12.2 (0.2)

|

|

|

|

2013

|

11.5 (0.2)

|

|

|

|

|

SEM = standard error of the mean. Source: Admitted Patient Data Collection, NSW Ministry of Health Secure Analytics for Population Health Research and Intelligence (SAPHaRI). Data extracted on 1 June 2015.

|

more_vert

more_vert