Chronic non-cancer pain is highly prevalent in our communities and its optimal management is crucial to the health and wellbeing of the community.1 Without good control of chronic pain, our community faces a level of avoidable suffering that cannot be justified, with costs of uncontrolled chronic pain borne across society by individuals, health services and businesses.2,3 At both the level of the individual patient and the community, there needs to be focus on using the best available evidence to assess and manage this overwhelming problem. Part of the appropriate treatment for many people will include opioid analgesics for acute pain at least for days to weeks.4 Simultaneously there is increasing pressure to ensure that prescribing of opioid analgesics is minimised to reduce the risk of dependence and illicit diversion. This is a difficult balance to strike, even with initiatives such as prescription drug monitoring programs.5

This article provides a brief overview of the current evidence to guide opioid use for chronic non-cancer pain in general practice.

Chronic pain: definitions and epidemiology

The International Association for the Study of Pain defines chronic pain as that which has persisted beyond normal tissue healing time; by convention, this is usually interpreted as pain that lasts for more than 3 months.6 Definitions for the duration of pain, intensity and level of interference with daily activities vary around the world. In the adult Australian population, pain has been defined as chronic if experienced daily for three of the past 6 months.1 Prevalence varies with the definition of chronicity.7,8

Chronic non-cancer pain is a major health problem around the world with prevalence rates as high as 33% of the population in western populations.9 It is prevalent across our communities, with up to 17.1% of men and 20.0% of women in Australia likely to experience the problem.1 These rates are comparable to those found in Denmark and Canada.10 Much higher rates have been reported from the United Kingdom, where rates may be as high as 46.5% of the population.11 Pain that interferes markedly with daily functioning has a rate in Australia of 5.0% of the population, with the strongest predictor being a work-related injury in an adjusted model with an odds ratio of 19.3 (95% CI 7.30–51.30; P < 0.001).12

The most frequently identified pains are those affecting the lower back and from osteoarthritis.11 As expected, the prevalence of pain increases with age, with some of the highest rates seen in residential aged care facilities.13 Chronic neuropathic pain is estimated to occur in one in 11 people.14

Chronic prescribing has been defined as 90 days or more of opioid prescribing in the past 120 days;15 this definition is congruent with that of the International Association for the Study of Pain.6

Current guidelines for safe prescribing of opioids for chronic non-malignant pain

The two most current and comprehensive evidence-based guidelines for the use of opioids for chronic non-cancer pain come from the United States and Canada.16,17 They share the stated purpose of ensuring the appropriate management of chronic non-cancer pain while minimising abuse of opioids.

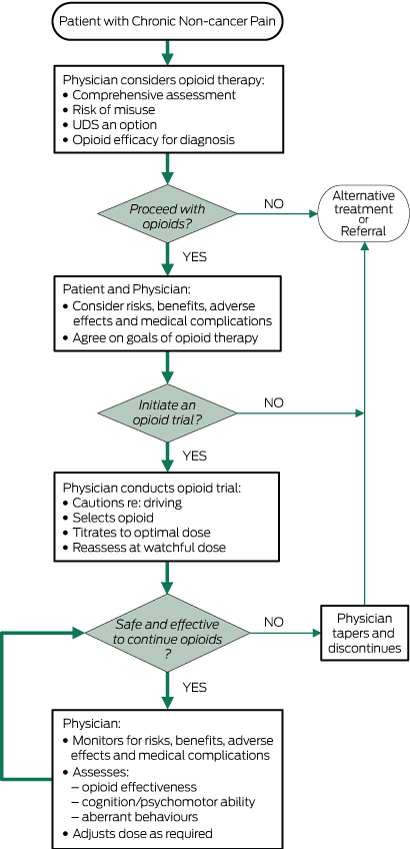

The Canadian guideline is for all practitioners working with chronic non-cancer pain, not just clinicians in specialist pain practice (Box 1).17 Major domains in considering such therapy are outlined in the document: assessing patients for the suitability for opioids; initiating a therapeutic trial of opioids and monitoring long term use. Sections are devoted to particular patient populations. One recurring theme in the clinical recommendations is to treat only “well defined somatic or neuropathic pain conditions when non-opioid alternatives have failed”.17 Care needs to be taken when deciding to initiate or titrate opioids, especially in more vulnerable populations who have relevant comorbid conditions, and great care is necessary if people require more than 200 mg of oral morphine equivalents. Another key theme is the need for the clinicians involved in a patient’s care to have clear lines of accountability with each other and for agreed communication strategies among treating clinicians.

Guidelines from the US stress that the use in the longer term (more than 3 months) of opioids for chronic non-cancer pain has little data to support the practice.16 However, in contrast to the Canadian guideline, the US guidelines suggest that doses of greater than 91 mg of morphine equivalent should be treated with caution and specialist advice sought. There is some evidence to support prescription drug monitoring programs and urine drug testing as mechanisms to reduce abuse potential. Less robust evidence supports a thorough patient assessment, risk-screening tools, controlled-substance agreements, careful dose titration, opioid dose ceilings, and adherence to practice guidelines reduces the risk of aberrant prescription drug-related behaviours.18

With respect to Australian recommendations, most recently the National Prescribing Service (NPS) has released a series of documents providing clinical advice for health professionals engaged in the care of people with chronic pain. This includes a section titled “Best practice opioid analgesic prescribing for chronic pain”, with the Australian recommendations similar to those of the US suggesting that daily doses above 100 mg morphine equivalent should be avoided. Further, recommendations made by the NPS include the fact that when commencing opioids, initial doses should be low with careful and supervised titration.19 A summary of the NPS recommendations is included in Box 2.

Current prescribing trends in Australia

Australia continues to experience rising rates of opioid prescription.20 Between 1992 and 2012, Australian opioid dispensing episodes increased from 0.5 million prescriptions to 7.5 million, with no evidence to suggest that these figures are reaching a plateau.21 There has also been an increase in the number of opioid preparations available (n = 241), including morphine (n = 87), fentanyl (n = 43) and oxycodone (n = 37) as the largest three groups.21 The indication on the Pharmaceutical Benefits Scheme generally includes use for chronic severe disabling pain that is not responsive to non-opioids. The variation in opioid prescribing across Australia has recently been highlighted in the Australian Atlas of Healthcare Variation published by the Australian Commission on Safety and Quality in Health Care (http://www.safetyandquality.gov.au/atlas).

The overall increase in opioids in Australia likely reflects a population that continues to grow rapidly in part because of increasing life expectancy with chronic illnesses of ageing often associated with pain, previous under-prescribing, increasing incidence and survival from cancer, increased numbers of preparations available, poor access to allied health for non-pharmacological interventions, poor undergraduate and postgraduate education about opioid prescribing, aggressive marketing and the imperative for health professionals to better manage pain.20

Clinical consequences of opioid use

Despite the prevalence of pain across the community, overall chronic non-cancer pain generally remains poorly treated, resulting in limitations in activity and diminished quality of life. Although there are a variety of strategies available to help manage chronic non-cancer pain, for many people opioids are prescribed long term. While some patients do achieve effective analgesia, an estimated 40–70% of people with chronic pain do not,22 with the balance towards those who appear not to benefit from opioids in the long term.23 It is important to consider how the long term use is balanced with the risk of short and long term adverse effects of opioids.

Shorter term harms

Typically shorter term side effects are considered unpleasant but unlikely to lead to long term consequences (Box 3). Data from a systematic review suggest that for every four patients commenced on opioids, at least one person would experience at least one of these effects in a 1–8-week period.24

Longer term harms

Longer term harms may include physical and psychological issues and dependence. (Box 4) While most of the adverse effects that occur when opioids are commenced are expected to resolve rapidly,25 the adverse effects of constipation, sedation or dizziness for some people may not settle, all of which can cause significant morbidity. Older patients taking the equivalent of at least 50 mg of morphine daily have a twofold risk of sustaining a fracture as a result of a fall.26

Opioids may contribute to acceleration of loss of bone mineral density in the long term and to hypogonadism because of their suppression of hypothalamic gonadotrophin-releasing hormone. This can lead to amenorrhea or oligomenorrhea in premenopausal women and erectile dysfunction in men.27 There is also a 28% increase in the risk of myocardial infarction for people taking opioids long term.28

Psychological impacts include higher rates of depression after chronic opioid therapy is initiated in people who were not previously depressed. In this same cohort, higher rates of anxiety, lower self-efficacy and a tendency towards catastrophising were seen regardless of the opioid doses.29

People who use opioids long term for chronic non-cancer pain are at greater risk of misusing them, including through psychological dependency and overdose. These problems are prevalent in this cohort, with rates of misuse (21–29%) and addiction (8–12%) a cause for grave concern.30

The risk of sudden death due to opioids is amplified in the context of concurrent benzodiazepine and/or alcohol (mis)use.31

Aside from the direct adverse effects of opioids, there are several other potential negative consequences. There is a subset of people who are not concurrently using other agents such as alcohol, who are on modest doses of opioids and not currently experiencing high levels of pain, for whom driving is likely be to be safe.32 In Australia, recommendations include the suggestion that people should not drive if they feel drowsy or impaired. Further, due to the persistent miotic effects, driving at night is discouraged. If there are concerns regarding capacity, a practical driving assessment may be requested by health professionals with the details as to how to achieve this in each state, dependent on the local driver-licensing authority.33 Proper assessments of capacity are important given that health service use increases with opioid use. Higher rates of hospitalisations, emergency department presentations and even unintentional death have been recorded.31,34 The evidence that supports the benefits outweighing the risks of long term opioids for chronic pain is very poor. There is real need for further research to most clearly define which patients are most likely to benefit from opioids and what are the most suitable precautions to safeguard them from harm.35

GPs’ attitudes to prescribing opioids for chronic non-cancer pain

Despite the development of various guidance documents for the safe and effective use of opioids,17,19,36,37 GPs continue to be concerned about the risk of opioid dependence and misuse for patients with chronic non-cancer pain. There are also concerns expressed by GPs about their capacity to manage the complex physical and psychological needs of this patient cohort, and their role in long term prescribing and the limitations of available treatment approaches.38–41 Regional difference in opioid-prescribing confidence has been noted in a pan-European online survey of primary care pain management practices.41 GPs in Norway (46%), Sweden (43%) and Poland (37%) reported lower levels of opioid-prescribing confidence, which they attributed to fears of addiction and adverse events.41 GPs in the UK, the Netherlands, France and Italy were more confident about prescribing opioids for patients with chronic non-cancer pain, which they attributed to their experience and the therapeutic treatment choices available.41

Opioid prescribing in primary care is complex because of the need to optimise pain management while balancing the risks of tolerance and addiction.37 Inappropriate prescribing is more likely when patients are exposed to repeated consultations that do not meet their needs and if GPs feel powerless to negotiate an alternative plan of care and set appropriate boundaries.38,42 If there is a perceived paucity of treatment alternatives, opioid prescribing can occur as a default decision.38 Variations in opioid prescribing have previously been linked to GPs’ pain management training, experience and exposure to adverse opiate-related events.43

What can be done to reduce inappropriate prescribing?

While there are opportunities to address inappropriate prescribing at the system, provider and patient levels, one of the most immediate changes could be achieved simply by supporting GPs to manage patients’ chronic non-cancer pain in accordance with recommended guidelines.39

Evidence-based guidelines provide GPs with an evidence-based framework for the collaborative development of a treatment plan with the patient.37 There are also opportunities to strengthen safe opioid prescribing by GPs for non-malignant pain through specific education programs.44 Combining clinician education with an opioid dose limitation practice policy45 and implementing a practice policy of not providing repeat opioid prescriptions or authorising a dose increase without a formal medical review may reduce the risk of inappropriate dose escalation.38

High level evidence supports the use of methadone or buprenorphine in patients with chronic non-cancer pain who are addicted to opioids (high level evidence).17

Indications to prescribe or not prescribe chronic opioids

Only carefully selected patients should be considered for long term opioids for chronic non-cancer pain that is moderate to severe, has led to substantial negative impacts on daily living and has failed all other analgesic modalities and adequate allied health assessments.46 Any concerns about the prevalence of opioid prescribing must be balanced with ensuring that people with opioid-responsive pain are adequately treated.47 Evidence is slowly building to refine prescribing guidelines, maximising benefits and minimising harms.48 Many of the more routine pain problems such as chronic back pain or chronic headaches are unlikely to respond to opioids, in contrast to more severe and physically disabling problems such as destructive rheumatoid arthritis.34

Managing aberrant patient behaviour

Aberrant behaviour related to prescription medications includes any behaviour that suggests non-medical use of a drug or evidence of addiction, such as drug-seeking behaviour, alternative routes of delivery, obtaining opioids from other sources or unsanctioned use.39 Preventing aberrant drug-related behaviour requires minimising the risk of opioid misuse while optimising the best evidenced-based treatments for patients with chronic non-cancer pain. In order to minimise harm, these patients require an approach that is similar to other chronic illness interventions, which includes appropriate non-pharmacological and pharmacological approaches, and an individualised evidence-based risk-mitigation plan to optimise adherence.39 There is good evidence that determining the treatment goals of pain relief and improved function can minimise the risk of aberrant behaviour.37 Prescribing tamper-resistant opioids currently offers the highest level of prevention of opioid misuse.18

If a patient with chronic non-cancer pain requests an early opioid prescription, it is important to consider the possibility that the patient may have developed tolerance to the opioid, thus requiring a higher dose to maintain the same level of pain control; developed physical dependence and is experiencing early withdrawal symptoms; diverted some or all of his or her opioids for financial gain; or that a third party may have diverted the prescribed opioids.49 Once aberrant behaviour has developed, management becomes more complex and is likely to require a range of responses including urgent referral to specialist services, urine drug screening and other compliance monitoring, treatment agreements, and patient education. High level evidence suggests that when combined, these measures can reduce substance misuse by 50%.50

Ensuring adequate prescribing when indicated

Promoting and implementing the guidance offered by recently updated guidelines and providing clinicians with point-of-care resources can help to ensure adequate and safe opioid prescribing for patients where opioids are indicated. In patients with acute pain, both the US and Canadian guidelines suggest that opioid therapy may be initiated with low doses and short-acting drugs with appropriate monitoring to provide effective relief and avoid side effects.17,48 Further, the US guidelines suggest that in well selected populations, chronic opioid therapy may be continued (≥ 90 days), with continuous adherence monitoring, in conjunction with or after failure of other modalities of treatments, with improvement in physical and functional status and minimal adverse effects.37

In addition to prescribing practices, greater emphasis on chronic pain management during initial medical training programs and access to point-of care pain management guidelines is required to better support GPs to manage opioid prescribing for people with non-malignant pain.40,41 Improved access to allied health services when pain is still acute is crucial if the prevalence of chronic, non-cancer pain is to be reduced substantially.

Box 1 –

Roadmap for safe and effective use of opioids for chronic non-cancer pain: Canadian guideline17

Box 2 –

Best practice opioid analgesic prescribing for chronic pain: National Prescribing Service19

When trialling an opioid:

- limit the trial to 4 weeks and only after exploring all other treatment options, both physical and psychological

- review weekly preferably with a family member

- encourage the use of a pain diary with a validated pain assessment tool such as the Brief Pain Inventory

- assess for measureable improvements in quality of life (sleep, mood, libido), function (activities) and pain scores to gauge the effectiveness of opioids during the trial phase

- along with monitoring physical and mental condition, monitor other key areas of function such as fitness for driving, work and other activities, and check for aberrant drug-related behaviours

- avoid short-acting opioids

Dosing:

- start with low doses and titrate according to response and adverse effects

- doses above the equivalent of 100 mg morphine per day require reassessment, including specialist advice if possible

- exercise caution with older patients

Management plans and contracts:

- an opioid contract that summarises conditions of use along with a management plan that outlines other activities can help set realistic goals and expectations of behaviour while undertaking an opioids trial

Box 3 –

Frequently encountered effects of opioids compared with placebo in short term use24

|

No. of trials

|

No. of participants

|

Side effect

|

Participants experiencing side effect

|

No. needed to harm*

|

|

Opioids

|

Placebo

|

|

|

8

|

1114

|

Constipation

|

41%

|

11%

|

3.4

|

|

8

|

1114

|

Nausea

|

32%

|

12%

|

5.0

|

|

7

|

1022

|

Sedation

|

29%

|

10%

|

5.3

|

|

7

|

972

|

Vomiting

|

15%

|

3%

|

8.1

|

|

8

|

1114

|

Dizziness

|

20%

|

7%

|

8.2

|

|

6

|

981

|

Itching

|

15%

|

7%

|

1.3

|

|

7

|

677

|

Dry mouth

|

13%

|

9

|

–

|

|

|

* Short term; reverses immediately with cessation.

|

Box 4 –

Definitions of misuse, abuse and addiction30

|

Term

|

Definition

|

|

|

Misuse

|

Opioid use contrary to the directed or prescribed pattern regardless of the presence or absence of harm or adverse effects

|

|

Abuse

|

Intentional use of the opioid for a non-medical purpose such as euphoria or altering of one’s state of consciousness

|

|

Addiction

|

Pattern of continued use with experience of, or demonstrated potential for harm with a psychological dependence

|

|

|

|

more_vert

more_vert