The known Self-poisoning is less common among older people, but the numerous medicines they often use provide a ready source of toxins. Further, multiple comorbidities may exacerbate their toxicity and hinder recovery.

The new Most self-poisoning by older people was intentional, but the proportion of unintentional poisonings increased with age. Hospital length of stay, rates of intensive care unit admission and cardiovascular adverse effects, and mortality were higher among older patients.

The implications As our population ages, self-poisoning by older people is likely to be an increasing problem. Although self-poisoning is associated with higher morbidity and mortality than in younger patients, the risk of a fatal outcome is low when patients are treated in specialist toxicology units.

As our population ages, self-poisoning and the associated morbidity are likely to be a growing problem. Self-poisoning is a burden on the health system and is a risk factor for subsequent suicide.1 Drug overdose is less common among older people than in younger adults,2 but is associated with higher morbidity and mortality.3–5 Distinct age differences in the nature and severity of self-poisoning have been reported.5 Stressors such as failing health, the death of a spouse, family discord, and loneliness may contribute to poisoning in older people.6 They often have several comorbidities and consequently take numerous medications, providing a ready source of toxins for self-poisoning. Further, multiple comorbidities and frailty may exacerbate the toxicity of these agents and hamper recovery from self-poisoning. Hopelessness and suicidality frequently increase with age, and depression is strongly associated with suicidality in older people. There is also a relationship between medical and psychiatric comorbidities and suicide by older people.7

While poisoning generally occurs in the context of deliberate self-harm or drug misuse, declining cognitive function can also be associated with unintentional overdose in older people.5 A recent report on self-poisoning in Australia8 provided only limited information about drug overdoses in older people, while an earlier, small study of deliberate self-poisoning by mature Australians included data only to July 1998.9

We examined the epidemiology and severity of self-poisoning by older people in a large regional centre in eastern Australia over a 26-year period, including in-hospital morbidity and mortality, and changes over time in the medications most commonly involved in self-poisoning. We compared these data with those for overdoses in a younger population.

Methods

We undertook a retrospective review of prospectively collected data for people presenting to the Hunter Area Toxicology Service (HATS) after self-poisoning during the 26-year period January 1987 – December 2012. Since 1987, HATS has provided a comprehensive 24-hour toxicology treatment service for a population of about 500 000 people. HATS currently has direct clinical responsibility for all adult poisoning patients in all hospitals in the greater Newcastle region, and provides a tertiary referral service to Maitland and the Hunter Valley.

HATS routinely records data for patients who present to hospital (even if the poisoning is uncomplicated) in a purpose-built database.10 A structured data collection form is used by HATS to prospectively capture information about patient demographics (age, sex), the drugs ingested, co-ingested substances, previous suicide attempts, whether the overdose was intentional or unintentional, management (including intensive care unit [ICU] admission), and complications of poisoning (hypotension, arrhythmias, ventilation requirement, death).11 At discharge, further information is collected, including hospital length of stay [LOS], and psychiatric and substance misuse diagnoses. Data are routinely entered into a fully relational Microsoft Access database distinct from the hospital’s main medical record system.

Data for all patients aged 65 years or more who presented following self-poisoning were extracted, analysed and compared with data for patients less than 65 years of age.

Statistical analysis

Continuous variables are reported as medians and interquartile ranges (IQRs) or ranges, and dichotomous variables as percentages. The statistical significance of differences in continuous variables was assessed in Mann–Whitney U tests, and of differences in dichotomous variables in χ2 tests (with Yates correction) or Fisher exact tests. P < 0.05 was deemed statistically significant. All analysis and graphics were performed in GraphPad Prism 6.0h (GraphPad Software).

Ethics approval

The Hunter New England Human Research Ethics Committee has previously granted an exemption from formal ethics approval for analysing data from the HATS database and patient information for research purposes.

Results

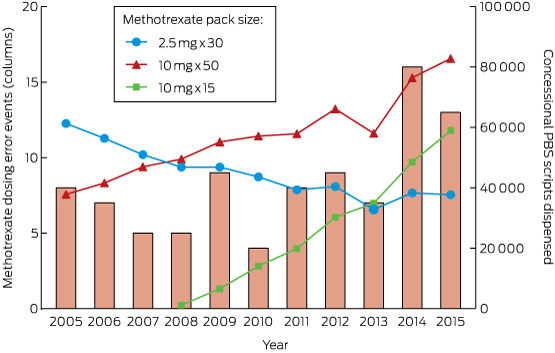

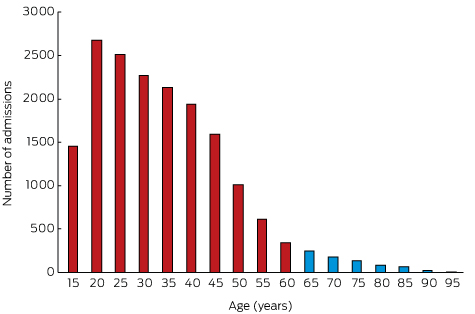

There were 17 276 admissions for self-poisoning over the 26-year period 1987–2012; 626 patients (3.6%) were aged 65 years or more and 16 650 (96.4%) were less than 65 years old. The older cohort included 344 women (55%), the younger group 10 258 women (62%; P < 0.001).

Changes in the epidemiology of the admissions of older patients over the 26-year period were analysed by dividing it into one 6-year and four 5-year segments. The proportion of patients admitted to hospital for self-poisoning who were 65 or older (3–4%) was relatively constant across the entire period. The median age of the older patients was 73 years (IQR, 68–79 years); that of the younger patients was 31 years (IQR, 23–41 years). There was a steady decline in the number of admissions for overdoses with increasing age (Box 1). Five hundred admissions in the older cohort (80%) and 14 837 in the younger cohort (89%) involved deliberate self-poisoning (P < 0.001). While the absolute number of self-poisonings decreased with age, the proportion of unintentional and iatrogenic poisoning admissions among patients over 65 increased (65–74 years, 15%; 75–84 years, 25%; 85–97 years, 34%; P < 0.001).

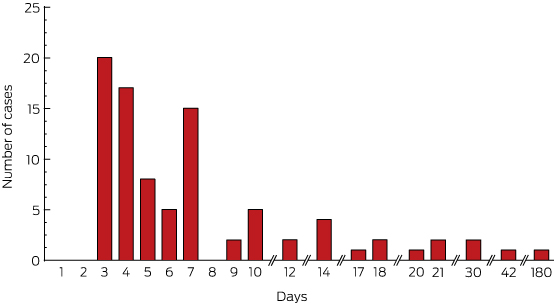

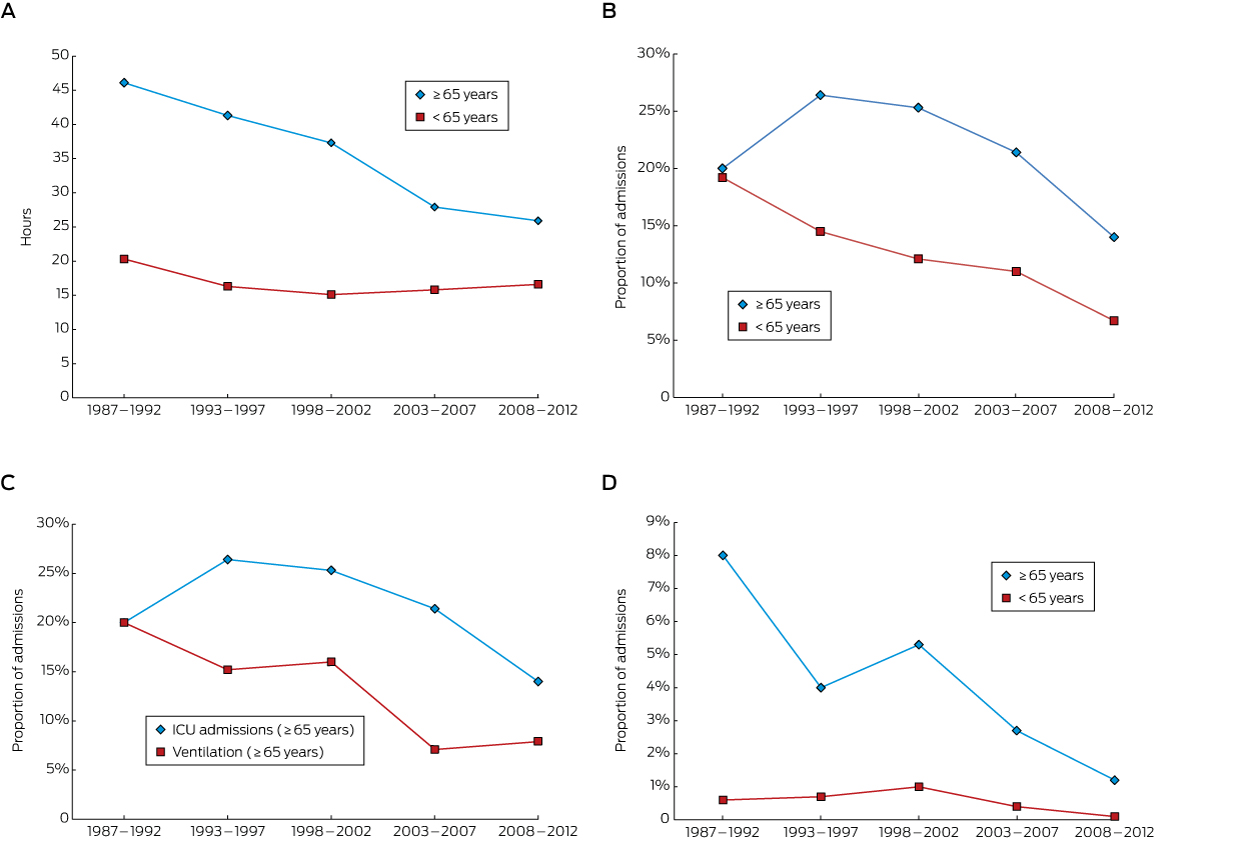

The median hospital LOS for the older patients across the entire period was 34 hours (IQR, 16–75 h); for the younger cohort, 16 hours (IQR, 9–25 h; P < 0.001). There was a progressive decline in LOS for the elderly cohort over the 26 years, from 46 hours (IQR, 23–86 h) in 1987–1992 to 26 hours (IQR, 14–35 h) in 2008–2012; in the younger cohort LOS was relatively constant across time (Box 2, A). The fall in LOS for older patients did not appear to be related to any change in self-poisoning rates with a particular class of drugs (data not shown).

In the older cohort, 133 people (21.2%) were admitted to an ICU, compared with 1976 of the younger cohort (11.9%; P < 0.001). The proportion of older patients admitted to an ICU declined over the 26-year period from a peak of 26% in 1993–1997 to 14% in 2008–2012; there was also a decline for the younger group (Box 2, B). The decline in the proportion of older patients who were ventilated was similar to that for those admitted to an ICU (Box 2, C). There were 24 deaths (3.8%) in the older cohort and 93 (0.6%) in the younger cohort (P < 0.001). Mortality decreased over time in the older cohort, from 8% to 1%, but remained relatively constant (0–1%) in the younger cohort (Box 2, D). The most common drug/toxin groups involved in fatal self-poisoning in the older cohort were opioids (5 of 24 deaths) and organophosphates (3 of 24; Appendix 1).

The incidence of cardiovascular adverse effects was higher in the older cohort. Hypotension was present in 65 older patients (10.4%) and 813 younger patients (4.9%); 59 patients aged 65 or more (9.4%) had arrhythmias, compared with 217 patients under 65 (1.3%). There were no differences between the two groups in the incidence of delirium, serotonin toxicity, or seizures.

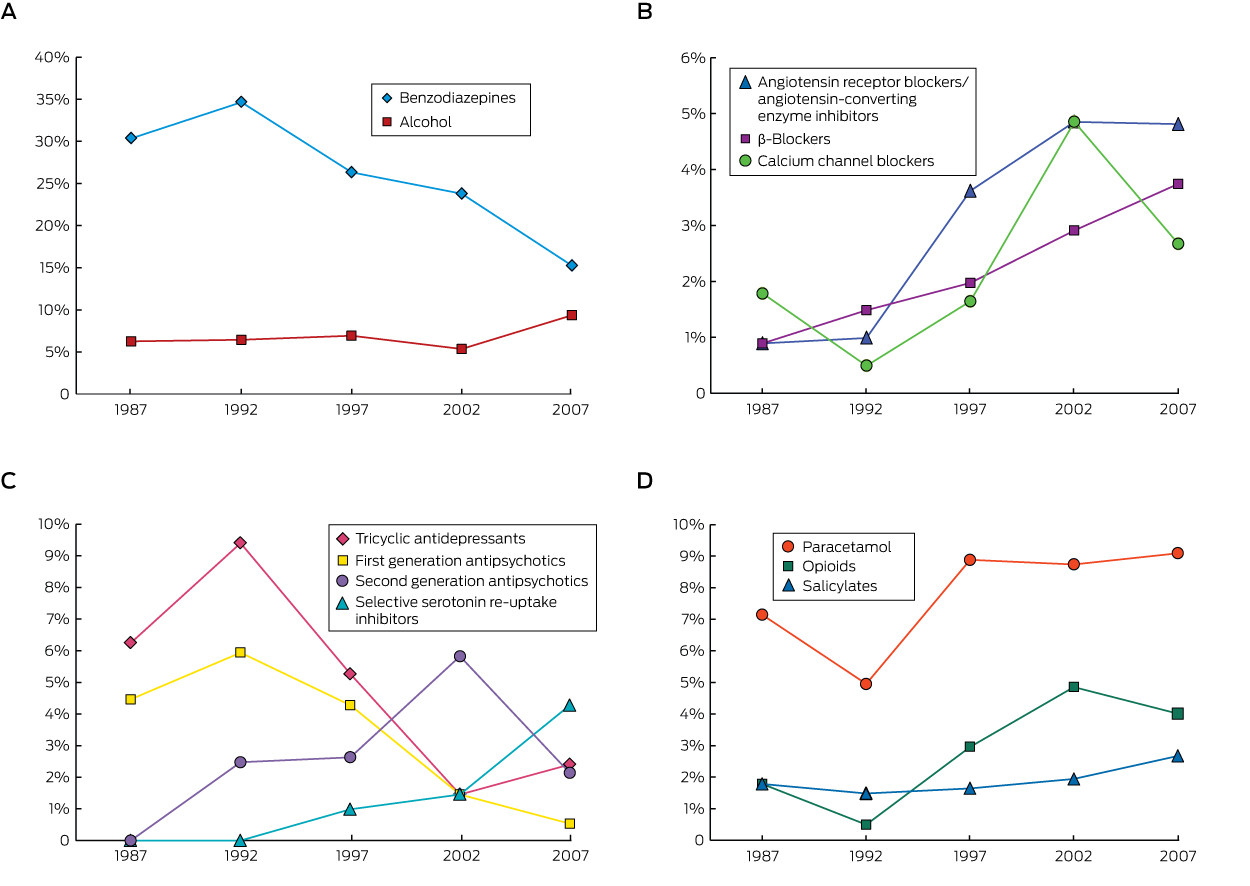

There were 356 single-drug ingestions (56.9% of admissions) in the older cohort, compared with 7009 (42.1%) in the younger cohort (P < 0.001), and 28 many multiple drug (ie, more than five) ingestions (4.5%) in the elderly cohort compared with 250 (1.5%) in the younger cohort (P < 0.001; Appendix 2). Benzodiazepines were the drug class most commonly ingested by older patients (24.2%), followed by paracetamol (8.1%) and alcohol (7.3%); in contrast, alcohol was the most common drug ingested by younger patients (16.2%), followed by benzodiazepines (15.6%) and paracetamol (14.0%; Box 3). The proportion of benzodiazepine ingestions among older patients decreased over the 26-year period from a high of 35% in 1993–1997 to 15% in 2008–2012 (Box 4, A). The proportion of cardiovascular drug ingestions (Box 4, B) increased threefold, from 4% to 11%, with about one-third of poisonings unintentional or iatrogenic. In contrast, only 2% of toxic benzodiazepine ingestions were unintentional or iatrogenic. The proportions of tricyclic antidepressant and first generation antipsychotic ingestions fell across the study period, with a corresponding increase in those of newer antidepressants and second generation antipsychotics (Box 4, C). The overall proportion of ingestions involving antidepressants or antipsychotics was unchanged over the study period, accounting for 12% of admissions. The proportion of poisonings with analgesic drugs (paracetamol, opioids or salicylates) increased by about 50% (from 10% to 16%); paracetamol accounted for 60% of toxic analgesic drug ingestions (Box 4, D), but there was a much greater increase in the proportion of poisonings with morphine and oxycodone. Only four admissions of older patients (0.6%) involved recreational drugs, compared with 1306 admissions (7.8%) in the younger cohort (P < 0.001).

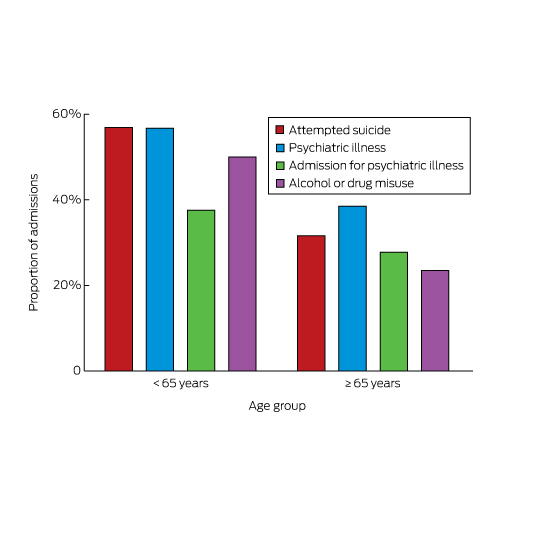

A history of previous suicide attempts, psychiatric illness, hospital admission for mental health problems, or drug or alcohol misuse was respectively identified for 198 (32%), 241 (38%), 174 (28%) and 147 (23%) admitted older patients. Each of these proportions was significantly smaller (P < 0.001) than for patients under 65 (Box 5).

Discussion

For people aged 65 years or more admitted to hospital for self-poisoning, the average LOS was twice as long, admission to an ICU more likely, the incidence of hypotension and arrhythmia significantly higher, and mortality greater than for younger patients. Hospital LOS for older patients steadily declined over the 26-year period, and this decrease was associated with a similar decline in the rates of ICU admission, ventilation, and mortality. This may reflect changes in management over time, with an increasing emphasis on reducing LOS, as well as improvements in services that aid older patients during the discharge process. A reduction in the proportions of self-poisonings with more toxic agents, such as tricyclic antidepressants and conventional antipsychotics, may have also contributed to the decline in LOS, although the number of admissions of older patients for self-poisoning with these drugs was small. Further, the reduced number of more toxic ingestions by the younger cohort did not affect their mean LOS over the study period (data not shown).

The proportion of patients admitted to hospital for self-poisoning who were at least 65 years old in our study (3–4%) was lower than the proportion of older people in the Australian population (11–14%) during the study period. Lower rates of admission of people over 65 years of age for poisoning with recreational drugs and the lower prevalence of psychiatric co-factors and alcohol and drug misuse probably explain this difference. Although the proportion of the population who were 65 or older increased during the study period, the proportion of self-poisonings involving older people remained relatively constant. This is reassuring, but underscores the importance of specialist toxicology services.

Among those aged 65 or more, the proportion of non-deliberate or unintentional self-harm admissions increased with age; the proportion was more than twice as great among the oldest patients as in the 65–74-year age group. In a profile of calls to a large American poisons information centre, therapeutic errors resulting in self-poisoning were increasingly prevalent among older people, rising from 14.5% in 50–54-year-old people to 25.3% in those aged 70 years or more.2 Psychiatric illness is associated with suicide at all ages,7 and 38% of older patients in our study had a history of psychiatric illness. Other risk factors for suicide include depression, alcohol misuse, prior suicide attempts, higher age, being male, living alone, and bereavement (especially among men).12 While in our study a history of psychiatric illness, a prior suicide attempt, and alcohol or drug misuse were all more frequent in patients under 65, one-third of older patients also had a history of attempted suicide, and almost one-quarter reported alcohol or drug misuse. Social isolation and loneliness, family discord, and financial trouble are also risk factors for suicide.6

In our study, opioids were the drugs most commonly associated with fatal self-poisoning by older patients. The rising proportion of opioid overdoses in this group is worrying, and may be reflect the increasing use of these agents, particularly for the treatment of non-malignant pain. While paracetamol was the second most commonly ingested drug in poisonings, the proportion has remained constant over time, and there were no fatalities, probably because a highly effective antidote, N-acetylcysteine, is available.13

Benzodiazepines were the drugs most frequently implicated in self-poisonings by older patients in our study, consistent with other reports. A Canadian study of 2079 people aged 65 or more found that benzodiazepines, opioids, other analgesics and antipyretics, antidepressants, and sedative hypnotics were the drug classes most frequently used in suicide attempts.5 In a Swedish study, a benzodiazepine was implicated in 39% of drug poisoning suicides by older people, and this proportion was rising despite a reduction in prescription sales.14 Both the prescription and ingestion of benzodiazepines have been reported to be associated with self-poisoning by older Australians.9 Benzodiazepines may exacerbate undiagnosed depression and impair impulse control in some individuals, leading to suicide attempts. The decline in the proportion of admissions for self-poisoning with benzodiazepines over the study period is therefore reassuring.

Self-poisoning with cardiovascular drugs by older people increased threefold over the study period, and probably contributed to the higher incidence of hypotension than in the younger cohort. In an American study of calls to a poisons information centre, there was a relatively high number of self-poisonings with β-blockers and calcium channel antagonists by older callers.2

The number of drugs taken by older patients appears to have a bimodal distribution, with the proportions of admissions for ingesting one drug or more than five drugs both being higher than among younger patients. The higher frequency of toxic ingestions of more than five drugs may reflect the increased use of Webster-pak and dosette boxes by older patients.

The data in our study have inherent limitations. The HATS database does not capture the number of people who died outside hospital, nor those with less severe poisonings; that is, people who visited their primary care physician rather than presenting to an emergency department. Other poisoning studies in Newcastle have also not included patients treated only by their local medical officer or in private hospitals.15,16 Further, despite the use of a prospective data collection form, retrospective review of medical records is often required to complement prospectively collected data. However, this is rarely required for the minimum dataset we analysed; almost all data were recorded at admission. Finally, the HATS database does not capture medical comorbidities, so that we were unable to correlate these with the outcomes we reported. The key strengths of our study include the fact that the longitudinal data were gathered over an extended period, and that core data fields were consistently recorded.

Education strategies for preventing poisoning have traditionally focused on children, but the morbidity and mortality for this age group is extraordinarily low.2 Although less common in older people, self-poisoning can be a highly significant clinical event. Suicidal intent is more common, as is a lethal outcome. Some prevention efforts may be better directed to protecting our expanding population of older citizens. The importance of potentially remediable factors, such as depression and rates of benzodiazepine prescribing, should not be overlooked. The overall low mortality among older people presenting to hospital after self-poisoning reflects the standard of care received by these patients.

In summary, self-poisoning by older people is likely to be an increasing problem as our population ages. Self-poisoning by older people is associated with higher morbidity and mortality than in younger patients, and unintentional self-poisoning is also more common. The steady decrease in LOS over the 26-year period and the declines in the rates of ICU admission and death are encouraging. Despite the higher overall rate of completed suicide by older people, our data indicate that the risk of a fatal outcome following self-poisoning is low when the patient is treated in a specialist toxicology unit.

Box 1 –

Number of admissions for self-poisoning, greater Newcastle region, 1987–2012, by 5-year age bands*

* Age group labels indicate the starting age for each band; eg, 15 years = 15 to less than 20 years of age.

Box 2 –

Median hospital length of stay (A), proportion of admissions to intensive care units (B), proportion of patients requiring mechanical ventilation (C), and in-hospital mortality (D) for patients admitted to hospital for self-poisoning, greater Newcastle region, 1987–2012

Box 3 –

Types of drugs most frequently ingested by patients admitted to hospital for self-poisoning, greater Newcastle region, 1987–2012, by age cohort*

|

Drug class/name |

Patients≥ 65 years |

Patients< 65 years |

|||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||

|

Total number of patients |

626 |

16 650 |

|||||||||||||

|

Total number of ingested substances |

1198 |

33 205 |

|||||||||||||

|

Benzodiazepines |

290 (24.2%) |

5180 (15.6%) |

|||||||||||||

|

Paracetamol |

97 (8.1%) |

4633 (14.0%) |

|||||||||||||

|

Opioids |

37 (3.1%) |

1221 (3.7%) |

|||||||||||||

|

Salicylates |

24 (2.0%) |

335 (1.0%) |

|||||||||||||

|

Alcohol |

87 (7.3%) |

5374 (16.2%) |

|||||||||||||

|

Tricyclic antidepressants |

54 (4.5%) |

1332 (4.0%) |

|||||||||||||

|

Selective serotonin re-uptake inhibitors |

33 (2.8%) |

1650 (5.0%) |

|||||||||||||

|

Serotonin/noradrenaline re-uptake inhibitors |

13 (1.1%) |

767 (2.3%) |

|||||||||||||

|

Antidepressants (other) |

15 (1.3%) |

428 (1.3%) |

|||||||||||||

|

Angiotensin 2 receptor blockers/angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitors |

42 (3.5%) |

178 (0.5%) |

|||||||||||||

|

β-Blockers |

30 (2.5%) |

259 (0.8%) |

|||||||||||||

|

Calcium channel blockers |

28 (2.3%) |

111 (0.3%) |

|||||||||||||

|

Digitalis glycosides |

14 (1.2%) |

20 (0.1%) |

|||||||||||||

|

Vasodilators |

13 (1.1%) |

154 (0.5%) |

|||||||||||||

|

Anticonvulsants |

39 (3.3%) |

1475 (4.5%) |

|||||||||||||

|

Antipsychotics (typical) |

35 (2.9%) |

1200 (3.6%) |

|||||||||||||

|

Antipsychotics (atypical) |

22 (1.9%) |

1673 (5.0%) |

|||||||||||||

|

Lithium |

22 (1.8%) |

228 (0.7%) |

|||||||||||||

|

Antihistamines |

16 (1.3%) |

727 (2.2%) |

|||||||||||||

|

Proton pump inhibitors |

15 (1.3%) |

129 (0.4%) |

|||||||||||||

|

Statins |

14 (1.2%) |

50 (0.2%) |

|||||||||||||

|

Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs |

13 (1.1%) |

1091 (3.3%) |

|||||||||||||

|

Other drugs |

85 (7.1%) |

1356 (4.1%) |

|||||||||||||

|

Nitrates |

14 (1.2%) |

22 (0.1%) |

|||||||||||||

|

Other non-therapeutic substances |

33 (2.8%) |

516 (1.6%) |

|||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||

|

* Three drug groups frequently implicated in self-poisoning by people under 65 years of age were rarely involved in self-poisoning by older patients: amphetamines (1.9% of admissions of people under 65), antibiotics (1.1%), and anticholinergic agents (1%). |

|||||||||||||||

more_vert

more_vert