This is a republished version of an article previously published in MJA Open

It is widely accepted that at least one in three patients with depression will not respond adequately to a series of appropriate treatments.1 There have been several approaches to defining this difficult-to-treat depression. One recently developed proposal is the Maudsley staging method — a points-based model of degrees of treatment resistance, which takes into account details of the specific treatments employed and the severity and duration of the depression.2 Another widely used and more straightforward definition is the failure to respond to two adequate trials of antidepressants from different pharmacological classes.3

Here, we use a pragmatic definition of difficult-to-treat depression — failure to respond to an adequate course of a selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SSRI) antidepressant. This was the definition used in the Sequenced Treatment Alternatives to Relieve Depression (STAR*D) trial in the United States,4 which was funded by the National Institute of Mental Health and is the single biggest study on sequenced treatment for depression and investigated rates of improvement in patients who had failed to respond to an SSRI. In this article, we draw liberally on the findings of the STAR*D trial, as well as other studies of difficult-to-treat depression.

The STAR*D trial used a series of treatment steps, premised on an initial failure to achieve remission after an adequate course of an SSRI. This approach reflects the reality of primary care and specialist treatment of depression in Australia (and most countries), whereby most patients who require antidepressants are initially treated with an SSRI. The trial recruited “real-world” patients with depression, including patients who are usually excluded from formal randomised controlled trials (RCTs), such as those with chronic symptoms, comorbid psychiatric and physical disorders, and substance misuse. STAR*D used a four-step approach for each patient, with the three potential steps after the initial SSRI comprising the main options developed over decades for difficult-to-treat depression: switching, augmenting or combining antidepressants. It used “remission” rather than the usual measure of “response” as its outcome. Remission refers to achieving nil or minimal depressive symptoms, whereas response is usually defined as a 50% reduction in symptoms. In clinical practice, both practitioners and patients aim for remission rather than response.

Studying almost 3000 patients, STAR*D found that, although 50% of patients responded to the initial trial of an SSRI, only a third achieved the more clinically meaningful outcome of remission. Furthermore, the final remission rate, even after four potential treatment steps, was only 70% (ie, 30% of patients did not remit with up to four different antidepressant treatment approaches). This finding reflects the reality of clinical practice and highlights the need to employ the best available evidence in the management of people with complex depression.

Two limitations of STAR*D need to be acknowledged: some of the treatment choices used are not approved for the treatment of depression in Australia, and there was a low retention rate of subjects in the latter phases of the trial.

In this article, we cover the main pharmacological strategies used in the management of difficult-to-treat depression (Box 1). The studies we refer to have mainly focused on patients with unipolar depression (major depressive disorder). While targeted towards people with difficult-to-treat major depressive disorder, some of the recommendations we give may also be relevant to those with difficult-to-treat bipolar depression.

A number of studies have demonstrated the value of increasing the antidepressant dose to the maximum tolerated level approved in the product information. While early RCTs reported the superiority of high-dose fluoxetine (60 mg/day) over some augmentation strategies,5 later systematic reviews found limited evidence to support high-dose SSRI usage in difficult-to-treat depression.6 However, there is stronger evidence for the effectiveness of increasing the dose of other categories of antidepressants, particularly tricyclic antidepressants (TCAs) and the serotonin–noradrenaline reuptake inhibitor venlafaxine.6,7 For some TCAs (but not other antidepressants), monitoring serum levels may be useful in achieving optimal clinical response.

There are three main issues to consider with this approach. Is switching to a second antidepressant an effective strategy? Does this switch need to be to a different class of antidepressants? When should a switch occur? Recent evidence has suggested that antidepressants may have a faster onset of action than initially thought,8 with most guidelines suggesting that treatment changes should be considered if no response is seen after 4 weeks.7

After failure to respond to initial treatment with an SSRI, there is strong evidence for switching to another antidepressant, but inconsistent evidence as to whether this needs to be a non-SSRI antidepressant or a different SSRI. One meta-analysis has reported a small but significant advantage (relative risk [RR], 1.29) of switching from an ineffective SSRI to a non-SSRI antidepressant (bupropion, mirtazapine, venlafaxine) compared with a second SSRI.9 In an RCT, venlafaxine was found to be superior to paroxetine in achieving response and remission.10 Other studies have reported that patients who had failed a trial with an SSRI responded to TCAs (imipramine,11 nortriptyline12). In an earlier study, patients who did not respond to two tricyclic antidepressants significantly improved with the monoamine oxidase inhibitor tranylcypromine.13 The STAR*D trial, however, demonstrated no significant differences in response rates between patients who switched to a second SSRI (sertraline) or to other classes of antidepressants (bupropion, venlafaxine).14 Consistent with this, a large systematic review concluded that treatment response was similar whether patients switched to a second SSRI or another class of antidepressants.15 Overall, and contrary to intuition, the accumulated evidence suggests no clear advantage of switching to a non-SSRI compared with a different SSRI.

Augmentation involves adding a non-antidepressant drug to ongoing antidepressant therapy to which there has been no or only partial response. Here, we review the evidence for several well studied augmentation strategies.

The evidence for lithium augmentation of antidepressants is very strong. One meta-analysis found lithium augmentation of TCAs and SSRIs significantly more effective in achieving response than augmentation with a placebo (odds ratio [OR], 3.11; 95% CI, 1.80–5.37), with a number-needed-to-treat of 5.16 Another meta-analysis reported a number-needed-to-treat of 3.8.17 Lithium augmentation was less efficacious in the STAR*D trial, but patients were prescribed suboptimal doses because of concern about adverse effects.18

The atypical antipsychotics studied as augmentation agents include risperidone, quetiapine, olanzapine and aripiprazole. Two meta-analyses have confirmed the efficacy of this strategy. The first included 10 RCTs and concluded that risperidone, quetiapine and olanzapine were effective as augmentation agents (RR, 1.75).19 The other meta-analysis reported similar findings for aripiprazole (OR, 2.0).20

One meta-analysis reported triiodothyronine (T3) augmentation of TCAs to be twice as likely to achieve response as placebo.21 A further meta-analysis found that T3 augmentation significantly accelerated the treatment response of TCAs.22 A systematic review that included three open-label studies and one RCT supported T3 augmentation of SSRIs.23 In the STAR*D trial, remission rates were not significantly different between patients with difficult-to-treat depression whose SSRI was augmented with T3 or lithium, but T3 augmentation was associated with a lower side-effect burden.18 Thyroxine (T4) augmentation has not been extensively investigated.

Lamotrigine is an anticonvulsant for which there is strong evidence of prevention of depressive recurrences in bipolar disorder.24 While early clinical reports suggested lamotrigine may have a similar effect in unipolar depression,25 two RCTs26,27 and a systematic review28 have so far failed to demonstrate significant reductions in depressive symptoms in patients with difficult-to-treat depression receiving lamotrigine augmentation.

Methylphenidate is used clinically for depressed patients with significant apathy and fatigue, particularly on the eastern seaboard of the US. Although early open-label studies suggested efficacy, two recent RCTs have reported no significant benefit of methylphenidate augmentation.29,30

Modafinil, which is less likely than other stimulants to cause dependence, has also been investigated as a potential augmenting agent, although at present data supporting its use are very limited.31,32

Pindolol has been reported to accelerate the speed of response to SSRIs. However, this β-blocker did not enhance the antidepressant action of SSRIs in three RCTs.33–35

It has been hypothesised that the synergistic effects of two antidepressants with different mechanisms of action may enhance response in difficult-to-treat depression. One of the earliest RCTs to test this theory reported greater efficacy from combining desipramine and fluoxetine, compared with monotherapy with either agent.36 Mirtazapine added to SSRI therapy was reported to improve outcome in one RCT.37 However, the widely used mirtazapine–venlafaxine combination was not found to be superior to monotherapy with tranylcypromine in a trial of patients whose depression had failed to respond to three medication trials.38 The citalopram–bupropion combination yielded similar remission rates in patients with difficult-to-treat depression as those who received augmentation with buspirone.39

It should be noted that while bupropion is approved as an antidepressant in the US, it has never been approved for this indication in Australia, where it is only approved for reducing craving on cessation of smoking. Prescribers also need to be aware of the risk of serotonin syndrome when combining two different antidepressants.40

As excessive glutamatergic activity has been hypothesised to cause depression, drugs that modulate N-methyl-d-aspartate (NMDA) receptors have attracted interest. Ketamine is an NMDA receptor antagonist, and ketamine infusion has demonstrated rapid (within 4 hours) and significant antidepressant effects in patients with difficult-to-treat depression.41 Riluzole, which decreases glutamate release and has been shown to be efficacious in treating amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, has shown promise in an open-label study of depression.42 There have been no RCTs of riluzole in depression or difficult-to-treat depression. Preclinical studies have suggested zinc, a non-competitive NMDA receptor antagonist, may be another augmentation option, but robust clinical trial data are currently lacking.43 In view of the cholinergic system being implicated in depression, agents that act on acetylcholine receptors are also being investigated. Scopolamine is an antimuscarinic drug that has been reported to significantly relieve depression in patients with major depressive disorder.44 Mecamylamine is a nicotinic acetylcholine receptor antagonist that showed promise in a preliminary study as an augmentation agent in patients responding poorly to SSRIs.45

Before adopting a new pharmacological strategy for a patient with difficult-to-treat depression, some general clinical issues should be considered (Box 2). Furthermore, the use of psychological interventions or other physical treatments such as electroconvulsive therapy (see Casey et al, Psychosocial treatment approaches to difficult-to-treat depression;46 and Fitzgerald, Non-pharmacological biological treatment approaches to difficult-to-treat depression47) should be considered at each step in management.

Although there is no strong evidence for the order of implementing pharmacological strategies for difficult-to-treat depression, we recommend the following: i) increase antidepressant dose; ii) switch to different antidepressant; iii) augment with a non-antidepressant agent; and iv) combine antidepressants (Box 3). Sometimes it may be more appropriate to consider augmentation before switching antidepressants, particularly if there has been partial response to the antidepressant treatment. In addition to the benefits associated with each of these options, prescribers need to be aware of the potential for side effects and the need for close monitoring with all of these strategies. In general, specialist assistance should be sought if augmentation or combining antidepressants is being considered.

2 Clinical factors to consider when assessing a patient with difficult-to-treat depression

-

Possible missed diagnoses such as bipolar disorder, major depressive disorder with psychotic features, other psychotic disorders such as schizophrenia, primary anxiety disorders, or primary personality disorders

-

Unresolved psychosocial issues (eg, ongoing relationship difficulties or unemployment)

-

Treatment non-adherence (consider measurement of serum antidepressant levels)

-

Rapid antidepressant metabolism (consider genotyping

of relevant metabolising enzymes, such as cytochrome P450 2D6) -

Inadequate antidepressant trial (ie, suboptimal dose

and/or duration) -

Comorbid psychiatric illnesses: anxiety disorders, substance use disorders

-

Comorbid medical illnesses: endocrine disorders

(eg, hypothyroidism), neurological disorders (eg, cerebral neoplasm, multiple sclerosis), autoimmune disorders

(eg, systemic lupus erythematosus) -

Concurrent medications: antihypertensives

(β-blockers, calcium-channel blockers), steroids, anti-Parkinsonian drugs (bromocriptine, levodopa) or interferon, which may exacerbate depression

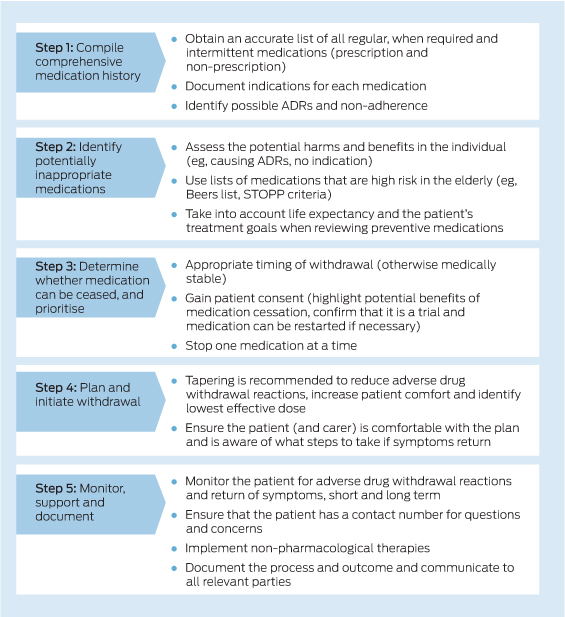

3 Pharmacological treatment recommendations for difficult-to-treat depression

1. Increase antidepressant dose

2. If nil or partial response, consider switching to another antidepressant

-

Different SSRI

-

Non-SSRI antidepressant (such as venlafaxine or other SNRI, mirtazapine, TCA, monoamine oxidase inhibitor or bupropion*)

3. If nil or partial response, consider augmenting with a non-antidepressant agent

4. If nil or partial response, consider combining antidepressants

SSRI = selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor. SNRI = serotonin–noradrenaline reuptake inhibitor. TCA = tricyclic antidepressant.

* Bupropion is not approved for the indication of depression in Australia.

more_vert

more_vert