Case presentation

A 63-year-old lean female of Asian ethnicity was referred to our service in 2006 with a 12-year history of well controlled type 2 diabetes (T2D) in the absence of micro- or macrovascular complications. She had undetectable β-cell antibodies. Her fasting glucose levels were 6–7 mmol/L and her glycated haemoglobin (HbA1c) level was 7.3% (56 mmol/mol). She was previously diagnosed with gestational diabetes mellitus (GDM) in three of five pregnancies, requiring insulin with the fourth pregnancy. All children were born without complication and of normal weight. Her father and five of six siblings were diagnosed with T2D. Over time, her management included diet and exercise, metformin 850 mg three times a day, modified release gliclazide 60 mg daily, and pioglitazone 45 mg daily. Ten years after referral, her HbA1c level was 7.6% (60 mmol/mol). She trialled basal insulin (glargine), but it was ceased as it was apparently ineffective. Her weight remained stable and her HbA1c levels showed little variation with escalating oral therapy. She developed postmenopausal osteoporosis and pioglitazone was ceased. Her daughter, who was also lean, was diagnosed with GDM during routine antenatal care. Given the autosomal dominant penetrance of diabetes in the family, she underwent genetic testing for maturity onset diabetes of the young (MODY) subtype 2 due to a glucokinase gene mutation (GCK-MODY), for which she tested positive. Our index patient also underwent genetic testing, and similarly tested positive for the same heterozygous mutation (aberrant splicing of intron 8c.1019+1G>A).

After being treated for more than 20 years, the patient was advised to cease treatment. She did so reluctantly, mainly due to the years of advice stressing the importance of treatment adherence. Her HbA1c level remained at 7.8% (62 mmol/mol) 3 months after treatment cessation. A 1-week continuous glucose monitoring study revealed fasting glucose levels of 7.5–8.4 mmol/L with the largest postprandial glucose excursion of about 3.0 mmol/L.

Literature search and sources

The sources used in this narrative review were obtained from original publications or reviews from groups renowned for their work in the definitions and genetics of MODY subtypes. Other publications were obtained from the MEDLINE and EMBASE databases and limited to English language; they were preferably recent publications (within < 10 years) and published in high impact journals. Information on specific genetic mutations and clinical phenotypes for the MODY subtypes were also obtained from the Online Mendelian Inheritance in Man online catalogue (www.omim.org).

What is MODY?

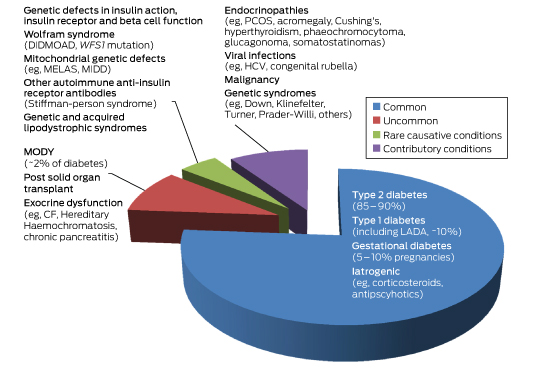

MODY is a heterogeneous group of monogenic diabetes disorders due to pancreatic β-cell dysfunction.1,2 Patients with MODY have early onset of diabetes and typically lack features of insulin resistance or autoimmunity. The MODY subtypes, of which there are currently 14, were first identified in the 1970s.3–5 They have an estimated population prevalence of 1.1:1000, or about 1–2% of diabetes cases (Box 1) in white Europeans, but are present in every race and ethnicity.6

The three most common MODY subtypes are mutations of hepatocyte nuclear factor 1A (HNF1A, MODY3), HNF4A (MODY1) and GCK genes. The GCK mutation, known as MODY subtype 2 (MODY2), or more recently as GCK-MODY, constitutes 10–60% of all MODY cases (Box 2).2,9–11 Rarer mutations resulting in β-cell dysfunction are also considered as separate MODY subtypes, and include alterations to insulin promoter factor 1 (MODY4), HNF1B (MODY5), and neurogenic differentiation factor 1 (MODY6) (Appendix). Patients with MODY5 constitute 5% of all MODY subtypes; MODY5 has been named the “renal cysts and diabetes syndrome,” as it often encompasses other urogenital malformations, pancreatic atrophy and deranged liver function tests.

The reference list includes succinct and lengthier reviews for further reading on MODY subtypes7,10,12,13 and on GCK-MODY.2,7,14

MODY subtypes 1 (HNF4A) and 3 (HNF1A)

Although driven by different mutations, the clinical phenotypes due to alterations of the HNF4A (MODY1) and HNF1A (MODY3) are best regarded as similar entities, because the features and management are similar.7,10,15 It is believed that mutations in HNF4A and HNF1A, which function as transcription factors, specifically result in dysfunction of the α, β and pancreatic polypeptide cells within pancreatic islets, resulting in reduced or delayed insulin secretion in response to glucose.15,16 In general, both MODY1 and MODY3 may present with mild diabetes, although usually postprandial blood glucose excursions are greater than those seen in GCK-MODY (ie, ≥ 5 mmol/L).17 Clinical features of MODY3, in addition to those listed in Box 2, include young onset diabetes usually before the age of 25 years in at least one family member, not normally requiring insulin initially, with generally good glycaemic control with less insulin than anticipated, detectable C-peptide in the presence of a blood glucose level (BGL) of over 8 mmol/L, family history spanning at least two generations, postprandial glucose excursions over 5 mmol/L with or without normal fasting glycaemia, absence of pancreatic autoantibodies and glycosuria when BGLs are under 10 mmol/L (given the low renal threshold for glucose wasting).18 These patients usually have a profound response to low doses of sulfonylurea therapy,16,19 with one randomised cross-over trial demonstrating about a 5-fold greater response with gliclazide compared with metformin. Patients also typically lack features of metabolic syndrome or insulin resistance (eg, obesity, acanthosis nigricans, elevated or normal high density lipoprotein cholesterol, and normal triglycerides).10,12

In contrast, MODY1 (HNF4A) is much less common, although the clinical features are similar to MODY3 (HNF1A), aside from a later age at diagnosis and the lack of pronounced glycosuria. Patients with MODY1 also share sensitivity to sulfonylureas. Offspring of women with MODY1 are often born with macrosomia (> 4.4 kg in 56% of carriers) and there may be transient neonatal hyperglycaemia.8 Clinical suspicion should be raised when there is a strong family history of pronounced macrosomia, or less commonly, if there is diazoxide (a medication used to treat hypoglycaemia) responsive neonatal hyperinsulinism in the context of familial diabetes.

Like T2D, both MODY1 and MODY3 are progressive forms of diabetes, and insulin secretion reduces over time.13 It is expected that micro- and macrovascular complications should be screened for, especially retinopathy and nephropathy. Treatment with insulin may be needed in 30–40% of affected individuals.12 Mutations in HNF4A favourably affect lipid biosynthesis and are associated with a 50% reduction in serum triglyceride levels and a 25% reduction in certain serum apolipoproteins.10

MODY2 (GCK-MODY) is often misdiagnosed

Based on the frequency of diagnoses, referral rates and prevalence in the United Kingdom, it is likely that GCK-MODY is underdiagnosed (or misdiagnosed as T2D) as more than 80% of patients with GCK-MODY do not undergo genetic testing.20 The condition is driven by an inactivating, heterozygous mutation of GCK, the glycolytic enzyme that catalyses the conversion of glucose to glucose 6-phosphate, the initial step in the chain of glucose metabolism in the β cell, consequently required for the release of insulin.21 In GCK-MODY, GCK is abnormal and functions at a higher glucose sensing threshold, earning its reputation as the “glucose sensor” of the β cell and the hepatocyte.22

The clinical phenotype is asymptomatic, mild hyperglycaemia present from childhood, usually ranging from 5.4 to 8.3 mmol/L. Most patients have an HbA1c level of 5.6–7.3% (41–56 mmol/mol) if they are less than 40 years old, or 5.9–7.6% (41–60 mmol/mol) if they are more than 40 years old.23

Special groups

All children with fasting hyperglycaemia need exclusion of GCK-MODY

Chronic childhood hyperglycaemia is exceptionally abnormal and, therefore, GCK-MODY along with type 1 diabetes (T1D) are the major differential diagnoses to consider, as GCK-MODY is present in 10–60% of all children with fasting hyperglycaemia.2 One cohort study of 82 children with fasting hyperglycaemia (BGL, ≥ 5.5 mmol/L) and negative β-cell antibodies found a GCK mutation in 48% of the cases.24 The major discriminating features favouring T1D are the presence of one or more islet cell antibodies, more pronounced hyperglycaemia, requirement for insulin within 5 years of diagnosis, and a stimulated C-peptide level lower than 200 pmol/L, as these are usually lacking in GCK-MODY.1,25

Pregnant women with GCK-MODY may need treatment

Epidemiological studies suggest that GCK-MODY is present in 1–2% of mothers diagnosed with GDM, and it usually presents as asymptomatic, mild fasting hyperglycaemia.6 A lower body mass index (BMI, < 25 kg/m2) and a fasting glucose level greater than or equal to 5.5 mmol/L have sensitivity and specificity of 68% and 96%, respectively. It is estimated that among lean women with mild fasting hyperglycaemia, the number of women needed to test is 2.7 to detect a single case of GCK-MODY.6 With new diagnostic thresholds adopted in Australia defining the diagnosis of GDM (ie, fasting BGL, 5.1–6.9 mmol/L),11 it is likely that more cases will be detected incidentally. Treatment in mothers with a known GCK-MODY mutation is indicated only if the fetus has a confirmed normal genotype (via chorionic villus sampling or amniocentesis) or if there is sonographic evidence of accelerated fetal growth on ultrasound, since this likely reflects fetal hyperinsulinaemia as the fetus attempts to overcome maternal hyperglycaemia. Treatment is with insulin, which is normally ceased postpartum.2,26,27

Diagnosis

Mild, fasting hyperglycaemia in younger, slimmer patients

There are no distinct clinical features of GCK-MODY. Suspicion is based on the findings of persistently elevated fasting hyperglycaemia (5.4–8.3 mmol/L), HbA1c levels of 5.8–7.6% (40–60 mmol/mol), young age (< 30 years old), non-obese phenotype, post-prandial glucose excursions lower than 3 mmol/L, and autosomal dominant pattern of inheritance of diabetes.2,7 With respect to the latter, a strong clinical clue is that many relatives of patients with known GCK-MODY will have been diagnosed with prediabetes, T1D or T2D, yet they rarely require insulin despite being diagnosed for many decades, and seemingly few, if any, develop complications. Despite this, about 20% of family members with GCK-MODY receive treatment with oral hypoglycaemic therapy and a minority with insulin.4,28,29

Genetic testing is the gold standard

Confirmation of GCK-MODY is performed by molecular genetic testing using Sanger sequencing and requires 5–10 mL of ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (EDTA)-treated blood. There are over 620 gene mutations identified throughout the ten pancreatic β-cell exons of the GCK gene in more than 1400 families.30 Samples can be sent to a number of laboratories.31,32 For example, one laboratory’s cost and processing time (4–8 weeks) will depend on whether the mutation is known to be due to a GCK mutation (cost ∼ $600) or either of HNF4A or HNF1A (∼ $800).2 A 16-gene MODY panel may also be requested for about $1145. Local laboratories can also perform the analysis for GCK mutations for $745 with a turn-around time of 4 weeks.32 Other mutations (ie, HNF4A, HNF1A) may be analysed by requesting a MODY 10-gene panel (next generation sequencing), inclusive of GCK gene mutation testing. A 4 mL EDTA blood sample is required (or 2 μg genomic DNA) and the cost is about $1100 with a 4-week turn-around time. As whole genome sequencing becomes more widely available, testing for heritable diabetes syndromes will become easier to access and new syndromes will be discovered (this information is current at the time of printing).

Testing patients greatly influences management

Because a diagnosis of GCK-MODY will significantly alter management, the clinician should be alert for suspected cases and refer suitable patients for genetic testing. However, as our case illustrates, in patients treated with diabetes medications for many years, the physician should discuss testing in an unbiased manner, without assuming that the patient will embrace a positive result that will allow them to cease therapy. If patients are amenable to ceasing treatment, as in our patient, this may cause significant stress and anxiety due to a feeling of guilt and perceived future morbidity. This is due to multiple previous clinical discussions with the patient stressing the importance of treatment adherence and tight glycaemic control. This is similarly important in patients with MODY3, in whom a positive diagnosis allows cessation of insulin and a switch to a sulfonylurea, which is likely to have been administered in a basal-bolus regimen or via an insulin pump for many years. Patients should be alerted that confirming a diagnosis of GCK-MODY not only significantly influences the number of investigations and reduces the treatment burden to them, but it also carries implications for relatives who may be undiagnosed, with offspring having a 50% chance of inheriting the gene.

To treat or not to treat

Arguments against treatment

With the exception of pregnancy, GCK-MODY has been regarded as a lifelong subtle abnormality in glucose homeostasis that is not progressive and shows little deterioration over time.16,33 This is in contrast to MODY3 (20–50% of cases), MODY1 (∼ 5% of cases)7 as well as T1D and T2D. GCK-MODY should therefore be considered a distinct clinical entity.2 As the fasting hyperglycaemia is often mild, varies little with time, and rarely results in the development of micro- or macrovascular complications, treatment is thought unlikely to change clinical outcomes.2,33 In a recent, large cross-sectional study involving GCK-MODY patients with a mean duration of 49 years, patients developed only mild background retinopathy when compared with healthy controls. Moreover, macrovascular complications developed in 4% of GCK-MODY patients versus 30% in patients with T2D, possibly reflecting the more favourable lipid profile in this condition.33

It is also known that the mild fasting hyperglycaemia in patients with GCK-MODY is resistant to oral diabetes therapy as well as dietary changes, due to the altered set point at which glucose homeostasis is maintained by the loss-of-function mutation of GCK.28 Therefore, treatment may not alter a patient’s glycaemic control or their trajectory towards developing complications as a result of mild fasting hyperglycaemia.

Arguments for treatment

As with the rest of the population, which is affected by genetic susceptibility, advancing age and rising rates of obesity, patients with GCK-MODY may also concurrently develop the metabolic derangements typical of T2D, such as progression of insulin resistance and β-cell failure.34 For example, one retrospective study of 33 patients with GCK-MODY over an 11-year period illustrated a small but significant deterioration in fasting (6.8–7.1 mmol/L) and 2-hour glucose levels (8.2–9.0 mmol/L), as well as decreases in insulin sensitivity when baseline and repeat oral glucose tolerance tests were compared.34 This was also associated with a mean increase in BMI from 19.2 to 22.3 kg/m2. More recently, it has been suggested that patients with GCK-MODY should be considered for treatment when the HbA1c level clearly and repeatedly exceeds 7.6 (60 mmol/mol).2,23 However, the question of whether to treat or not, based on a specific HbA1c level in patients with GCK-MODY, remains controversial; notwithstanding, HbA1c itself has limitations in predicting the development of microvascular complications.35

The verdict is divided

The decision to treat the patient should take into consideration the patient’s age, the current mild to moderate hyperglycaemia, the observation of postprandial glucose intolerance, the patient’s preference and the suboptimal HbA1c level, which may increase the risk of both micro- and macrovascular complications. This is in the context of an anticipated trajectory of deteriorating glycaemic metabolism that often accompanies advancing age and weight gain. This would naturally be weighed against the risks, cost and inconvenience of multiple investigations and the need for medical appointments, frequent self-monitoring of glucose levels, cost of glucose test strips, as well as patient anxiety.36 Furthermore, many patients may suffer from side effects from pharmacologic therapy; notwithstanding, weight gain, hypoglycaemia (especially if on sulfonylurea or insulin), gastrointestinal upset and vitamin B12 deficiency with metformin, as well as the adverse metabolic consequences to bone metabolism, bladder cancer risk and heart failure with thiazolidinediones, as in our index patient, should be considered. To date, there are no data on the efficacy of dipeptidyl peptidase 4 inhibitors, glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonists, or sodium glucose cotransporter 2 inhibitors, in these patients. Therefore, a careful examination, by an attentive clinician, of the patient’s goals, quality of life, comorbidities and an estimation of benefit, should form the basis when considering the decision to treat.

Genetic testing is underutilised but may be cost-effective

The burden and cost, both personally and to the community, are difficult to estimate when considering the implementation of a screening strategy at a national level. A recent cost-analysis simulation of a one-time genetic screening test (with a cost of US$2580) for the three most common MODY subtypes (GCK, HNF1A, HNF4A) — which account for more than 90% of all MODY cases — within the first year of diagnosis, was undertaken in a hypothetical cohort of young individuals (aged 25–40 years old) with a diagnosis of diabetes.36 The study assumed that the prevalence of GCK-MODY was 6% (similar to other countries), and when diagnosed, patients with GCK-MODY received no treatment. The screening test yielded an average small gain of 0.012 quality-adjusted life years and an incremental cost-effectiveness ratio of US$50 000.36 The cost-effectiveness extends to children, and arguably more so, with savings of about €1500 per year from time of diagnosis, as intensive treatment for presumed T1D in children is reduced to conservative management in the case of a positive diagnosis of GCK-MODY.37

It is not just MODY; diabetes genes are common in the general population

It is worth noting that not all genetic causes of diabetes can be ascribed simply to monogenic (single gene) mutations such as in MODY, or that there are a small number of rare genes inherited within generational lines that specifically affect an individual’s risk of developing diabetes. This approach, although clinically useful, is simplistic and may inadvertently overlook the fact that, on the whole, the population carries multiple, common genetic alterations in a single gene (ie, variants) that may collectively increase the risk of developing diabetes.38 A recent large analysis of exomes (protein-coding regions which comprise a fraction, 1–2%, of the whole human genome), from 6500 subjects with T2D matched to an equal number of healthy controls from five ethnic groups, has cast doubt on the evidence that rare or low frequency disease-associated variants affect the risk of developing diabetes. The authors note that most of the diabetes-associated genetic variants are quite common in the population.39

Conclusion

Despite the availability of genetic testing, there are a significant number of patient- and physician-related factors that may be prohibitive to uptake, including the perceived lack of possibilities for treatment (if coexistent MODY and T2D develop over time, many would argue that it may not change management if hyperglycaemia is mild; however, we believe that it makes a difference to management and monitoring) and prevention, cost implications of a positive diagnosis to patients, and lack of awareness of MODY as a diagnosis.40 These factors should all be discussed with the patient when considering genetic or genomic testing. The patient should be counselled regarding the treatment implications of a positive diagnosis, including the possibility that they may have not required the treatment they were prescribed many years prior. The points raised by this review will be increasingly relevant to the medical practitioner given the rapid development of genetic and genomic testing.

Box 1 –

Subtypes of diabetes according to relative prevalence

Box 2 –

Prevalence, genetic and key clinical features of the common forms of diabetes and subtypes of maturity onset diabetes of the young (MODY)

|

|

Type 2 diabetes

|

Type 1 diabetes

|

Gestational diabetes

|

MODY1

|

MODY2

|

MODY3

|

|

|

Prevalence

|

1 in 13 people (∼ 870 000 in Australia)

|

10% of all diabetes (∼ 170 000 in Australia)

|

5–10% of all pregnancies

|

∼ 5%*

|

10–60%*

|

20–50%*

|

|

Causative mutation

|

Multiple polymorphisms (eg, class II HLA genes)

|

Multiple polymorphisms

|

Multiple polymorphisms

|

HNF4A7,8

|

GCK2

|

HNF1A10

|

|

Clinical features

|

Older (usually > 45 years), overweight or obese, often family history, insulin resistance

|

Slim, family history of autoimmune disorders, usually childhood or early adolescence or adulthood (includes LADA)

|

Older (> 40 years); pre-pregnancy obesity (BMI, > 30 kg/m2); family history (30%) and ethnicity; previous GDM; PCOS; macrosomic babies, diagnosed 24–28 weeks’ gestation

|

Young age (< 25 years), strong family history of diabetes, absent antibodies, detectable C-peptide

|

|

Diagnostic glucose and HbA1c

|

75 g OGTT: fasting BGL, ≥ 7 mmol/L; random or 2-h postprandial BGL, ≥ 11.1 mmol/L; HbA1c, ≥ 6.5% (48 mmol/mol)

|

Similar to type 2 diabetes

|

75 g OGTT: fasting BGL, 5.1–6.9 mmol/L;1-h, ≥ 10 mmol/L; 2-h, 8.5–11 mmol/L11

|

As with type 2 diabetes; postprandial glucose excursions, ≥ 5 mmol/L

|

Fasting BGL, 5.4–8.3 mmol/L; postprandial glucose excursions, ≤ 3 mmol/L, HbA1c, 5.8–7.6% (40–60 mmol/mol)

|

As for MODY1

|

|

Treatment

|

Diet, exercise, OHG, injectable GLP1 RA, insulin

|

Insulin

|

Diet, exercise, metformin, insulin

|

Respond to sulfonylureas, 30–40% apparent insulin-requiring

|

None required (controversial)

|

As for MODY1

|

|

Special features

|

Progressive β-cell dysfunction with development of micro- and macrovascular complications

|

Negative C-peptide and DKA without insulin (outside of honeymoon period), positive antibodies in majority to GAD, IA-2, ICA, IAA and ZnT8

|

Hyperglycaemia remits postpartum

|

Glycosuria common; develop micro- and macrovascular complications as in type 1 and 2 diabetes

|

Favourable lipid profile; lean; minimal or no micro- or macrovascular complications; minimal effect of treatment on glycaemic control

|

As for MODY1; strong family history of macrosomic babies

|

|

|

* Denotes approximate percentage prevalence of all MODY subtypes. DKA = diabetic ketoacidosis. GAD = glutamic decarboxylase autoantibody. GCK = glucokinase gene. GDM = gestational diabetes mellitus. GLP1 RA = glucagon-like peptide 1 receptor agonists. HLA = human leukocyte antigen. HNF1A = hepatocyte nuclear factor 1α gene. HNF4A = hepatocyte nuclear factor 4α gene. IA-2 = insulinoma-associated-2 autoantibody. IAA = insulin autoantibody. ICA = islet cell cytoplasmic autoantibody. LADA = latent autoimmune diabetes of the adult. OGTT = oral glucose tolerance test. OHGs = oral hypoglycaemic therapy. PCOS = polycystic ovarian syndrome. ZnT8 = zinc transporter 8 autoantibody.

|

more_vert

more_vert