Lung cancer is one of the most common fatal cancers in the world. In Australia, about 7500 patients die from lung cancer each year,1 and the median survival for those with metastatic non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) is 4–5 months.2 Despite improvements in survival, attention to symptoms and quality-of-life concerns form the mainstay of treatment for most patients.

Those with advanced lung cancer have a substantial symptom burden. Most patients experience appetite loss, fatigue, cough, dyspnoea and chest pain.3,4 In 2010, Temel and colleagues demonstrated that early introduction of palliative care integrated with standard oncological care for this population was associated with improved quality of life, reduced depression and less aggressive care at end of life.5 Following this, the American Society of Clinical Oncology released a provisional clinical opinion that patients with metastatic NSCLC “should be offered concurrent palliative care and standard oncologic care at initial diagnosis”, while national societies have endorsed timely palliative care referral.6,7

The aggressiveness of cancer care near the end of life has been proposed as an indicator of quality of care, and centres around the following criteria: overuse of chemotherapy near death; high rates of emergency department (ED) visits; hospital and intensive care unit stays; and underuse of hospice or palliative care services.8

A series of population-based studies of cancer care in the United States and Canada revealed the aggressiveness of care at the end of life had increased.9,10 Patients more likely to receive aggressive end-of-life care were young, male and rural based, experienced greater comorbidity burden, and had lung, breast or haematological malignancies.9,10

Given the recommendation for integrated palliative care services for patients with metastatic NSCLC, we sought to examine the end-of-life care for this patient group. Using routinely collected hospital discharge, ED and death certificate data for a cohort of patients with metastatic NSCLC, we aimed to examine their patterns of care. These included the aggressiveness of care, ED visits, intensive care use, timing of chemotherapy in relation to death, hospitalisation patterns, and place of death. We also aimed to determine patterns of referral to hospital-based supportive and palliative care services.

Methods

Setting

Palliative care services in Victoria, Australia, are organised into three main areas: acute hospital consultancy services; community palliative care services providing care in the patient’s residence; and specialist inpatient palliative care units. Our study sought to examine the use of hospital-based palliative care services (ie, the first and third areas above).

Data sources

Hospital discharge and ED data are compiled by over 300 individual hospitals and maintained by the Victorian Department of Health (VDH).11–13 The two datasets contain demographic and clinical information on each episode of patient care; their quality is maintained using an independent audit program.14,15 Death certificate data are maintained by the Registry of Births, Deaths and Marriages.13

These three datasets undergo step-wise deterministic data linkage at VDH.16 Linkage staff assess data quality by a series of internal logic checks and manual review of randomly selected case groups. Notably, these data report on patients who have had contact with the hospital sector only.

Metastatic NSCLC cases

Metastatic NSCLC cases were extracted based on a combination of three sets of codes: lung cancer, small cell morphology (excluded), and metastatic extension (Appendix). The first data point or entry to the study was defined as hospitalisation when both NSCLC and metastases were coded. We included only NSCLC patients who were diagnosed with metastatic disease and died between 1 July 2003 and 30 June 2010.

Outcomes

Supportive care was defined as consultation by one or more of the following services — social work, physiotherapy, occupational therapy, psychology or speech pathology — using Australian Classification of Health Interventions codes.17 Palliative care was defined as consultation with a hospital-based palliative care service.

Site of death was based on a combination of hospital and death certificate data and classified into three mutually exclusive groups: outside hospital; inpatient hospice or palliative care bed; and acute care hospital bed.

Aggressiveness of care (adopted from Earle and colleagues8 and using available dataset information) was defined by the following parameters in the last 30 days of life: more than one ED presentation; more than one hospital admission; length of stay more than 14 days; intensive care unit admission; and inpatient chemotherapy administration (including same-day admissions) within 14 days of death.

Statistical analysis

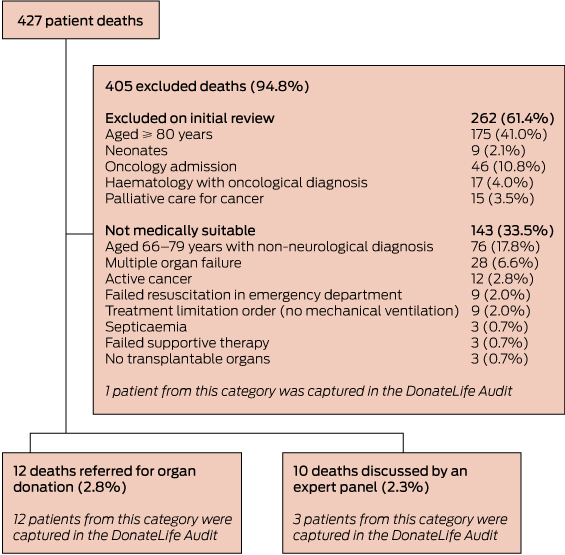

The illness course was divided into three distinct time periods based on key admissions: hospitalisation for first metastasis; interval between metastasis and just before final admission (for those who died in hospital) or death (for those who died outside hospital); and death admission for those who died in hospital (Box 1). The care was described at these time intervals using medians and interquartile ranges for continuous factors, and frequencies and proportions for categorical variables. A logistic regression model was fitted for the question: what factors predict the likelihood of death in an acute hospital bed? Stata version 13 (StataCorp) was used for all statistical analyses.

Ethics approval

This study was approved by the Monash University human research ethics committee.

Results

There were 6041 eligible NSCLC cases diagnosed with a first metastasis in the period of interest. Eighty per cent were aged ≥ 60 years and 63% were male (Box 2). At the first hospitalisation for metastatic disease, sites of metastases were: bone, 31%; lymph nodes, 36%; lung, 26%; brain, 19%; and 27% had more than one metastatic site.

Survival

Median survival after hospitalisation with first metastasis (ie, at point of entry into cohort) was 116 days, with 75% of patients (4551) surviving at least 43 days and 25% (1536) over 9 months (range 0–2324 days). This short median survival reflects our sampling frame, which included only those patients who died. Twelve per cent of patients (728) died during the first metastasis admission.

Place of death

Sixteen per cent of patients died outside of hospital, 42% in a palliative care unit, and 42% in an acute hospital bed (Box 2).

Patterns of ED and hospital use from diagnosis to death

Thirty-five per cent of patients (2104) were admitted through the ED at time of hospitalisation when metastatic disease was first coded. The proportion of patients receiving ED care was 58% for those who died during the first metastasis admission, and 42% for those who died in hospital after surviving initial admission (Box 3).

The proportion of patients receiving care in the private system reduced slightly over their cancer care, from 35% at first metastasis, to 28% at time of death.

The duration of the first admission where metastatic disease was diagnosed was a median of 43 days for those who died during this admission, compared with 6 days for those who survived the admission. Overall, patients spent a median of 38 days in hospital from first admission of metastatic disease until death.

A third of patients (1998) underwent a lung procedure (including pleuridesis, biopsy, bronchial stenting) during the admission when metastatic disease was first diagnosed, reducing to 6% during their death admission (Box 3).

Supportive and palliative care from diagnosis to death

Overall, 62% of patients were referred to palliative care (Box 2). In general, receipt of supportive care (96%) and palliative care (78%) were high for the 728 patients dying during the first metastasis admission. Sixty per cent were transferred to a hospice bed during this admission.

Of the remaining 5313 patients who survived the first metastasis admission, 10% were referred to hospital-based palliative care by time of discharge (Box 3). A further 22% were first referred to hospital-based palliative care in the interval between metastasis and death (or death admission for those dying in hospital), and 27% were referred for the first time when they returned to hospital to die.

Aggressiveness of care

In the last 30 days of life, 18% of 5313 patients surviving beyond the first metastasis admission had more than one hospital admission, and 5% had intensive care treatment. However, 61% spent more than 14 days in hospital, and less than 1% had chemotherapy in the last 14 days of life (Box 4). Thirty-three per cent (2010) were not flagged by any indicator of aggressive care.

Factors associated with place of death

For patients who survived the first admission with metastatic disease, 42% died in an acute hospital bed (Box 2). Factors independently associated with increased likelihood of death in an acute bed included treatment in the private system and a rural place of residence (Box 5). Meanwhile, receipt of palliative care at any point, receipt of two or more modalities of supportive care, and English as the primary language were associated with a greater likelihood of death at home or in a palliative care unit. Notably, those surviving at least 270 days after their metastasis admission were less likely to die in an acute bed compared with those surviving less than 90 days. There was no change in the likelihood of dying in an acute bed over the time of the study.

Discussion

Our study provides an overview of care for patients with metastatic NSCLC in Victoria, Australia. It found that 42% of patients who die due to NSCLC can expect to die in an acute hospital and 42% in a hospice setting, having spent a median of 38 days in hospital after the onset of metastatic disease.

Although the patients did not generally receive aggressive care in the form of intensive care unit treatment or chemotherapy in the last 14 days of life, other parameters of aggressive care — notably, death in acute hospital and ED visits — were common. Perhaps the most important finding is the low numbers of patients discharged from hospital following the diagnosis of metastatic disease who were referred to hospital palliative care services during the first admission for metastasis (10%). This is a group of patients with poor prognostic disease, who are not being identified as requiring palliative care services.

We propose that the care of people with metastatic NSCLC is a reasonable benchmark of the quality of end-of-life care or, more broadly, palliative care, for those with eventually fatal oncological disease. This is because metastatic NSCLC is associated with a poor prognosis (less than 4 months in our study) and a high symptom burden;2–4 has high-quality evidence of benefits from palliative care;5 and palliative care has been recommended as part of standard practice.6,18 Such key unambiguous reasons for routinely involving palliative care for patients with metastatic NSCLC may provide the ideal model for assessing the quality of end-of-life care provision.

In this context, our study shows that for metastatic NSCLC patients, where the case for palliative care is strong, gaps remain in service provision. For example, just 18% of patients overall received hospital-based palliative care services at the first sign of metastatic disease, including those who died during that admission; referral was far less frequent among those discharged from hospital. While this proportion increased to 62% overall, about a quarter of these patients first received palliative care services in the readmission that resulted in their death.

Palliative care referrals, when they do occur, appear often to be late in the illness. Poulose and colleagues highlighted the timing of referral to palliative care as important, suggesting that referral at least 30 days before death is associated with a greater chance of dying at home or in hospice,19 the preferred options expressed by most surveyed patients.20–22 Similarly, Earle and colleagues suggested that hospice admission 3 days or less before death is a marker of poor-quality care.8

In our study, referral occurred very late, at the time of death admission, for about a quarter of all patients surviving the initial admission with metastasis. This may not represent the first contact with palliative care services for all patients, as they may previously have been involved with community care, but it is likely to be the first contact for at least a significant number. Late referrals to palliative care diminish opportunities to institute community networks of support. Late referrals also do not allow sufficient time for patients and families to establish confidence in such networks. Our and other studies23,24 show that referral to palliative care services is an independent predictor of the likelihood of death outside the acute hospital and reduced hospitalisations, but it appears that time is required in order for this effect to be realised. In addition, late referral to palliative care necessarily truncates opportunities to attend to psychosocial and symptom needs.

Based on our proposition that metastatic NSCLC should represent a suitable benchmark for palliative care provision to oncology patients, it is worthwhile considering what may be the most pertinent quality indicator(s). In our study, 62% of patients were engaged with hospital-based palliative care services overall. This figure is high, and may be even higher since community-based care was not captured. Nevertheless, only 18% accessed palliative care during the admission when metastatic disease was diagnosed, potentially the most appropriate time to discuss the benefits of palliative care for this patient group. What level of palliative care should be considered the preferred standard of quality end-of-life care for metastatic NSCLC patients, and when should referral occur? Is the current proportion of 18% receiving palliative care at first admission with metastatic disease sufficient, or would 50% or even 90% of patients indicate better-quality care, in light of evidence that referral to palliative care at this time may prolong survival?5 Further, how should quality be judged in other diagnostic cohorts where the associated factors are ambiguous, such as when prognosis is longer?

Our study had several limitations. The analysis relied on routinely collected hospital data, so care events that took place outside hospital were not collected. This means that patients diagnosed with a metastasis as outpatients and never admitted were not part of our analysis. Similarly, community-based palliative care provision was not available in our dataset, and therefore receipt of palliative care is likely to be higher than we have reported. In Western Australia, this has been found to represent up to 24% of cancer patients.25 While local care patterns are likely to be influential, this community-only group may also be significant in Victoria. Oral chemotherapy regimens not requiring intravenous drug administration would not have been captured. Finally, our cohort included patients who were diagnosed and died within the follow-up period, which meant that particularly long survivors were not included. Nevertheless, our approach enabled us to document care during the whole illness period for those included, which was consistent with our focus on care at the end-of-life.

In conclusion, we sought to establish the current patterns of care and use of hospital palliative care for patients with metastatic NSCLC in Victoria. In this group, who we propose as a benchmark of quality end-of-life care, there was limited use of aggressive treatment measures such as intensive care and chemotherapy at end of life, although high numbers of people died in acute hospitals following a substantial length of stay. Most patients were referred to palliative care services, but this tended to happen later in the illness course. Future work is required to determine appropriate targets for quality end-of-life care in this and other cancer patient cohorts, with particular focus on timely palliative care engagement.

1 Schema of time intervals as basis for analysis

2 Demographic and clinical data (n = 6041)

|

Characteristic

|

No. of patients

|

|

|

Age

|

|

|

< 40 years

|

39 (1%)

|

|

40–59 years

|

1167 (19%)

|

|

≥ 60 years

|

4835 (80%)

|

|

Male

|

3815 (63%)

|

|

Australian born

|

3656 (61%)

|

|

English as primary language

|

4328 (72%)

|

|

Married

|

3869 (64%)

|

|

Rural residence

|

2058 (34%)

|

|

Histology

|

|

Adenocarcinoma

|

2081 (34%)

|

|

Large cell carcinoma

|

433 (7%)

|

|

Non-small cell, not further classified

|

1655 (27%)

|

|

Squamous cell carcinoma

|

877 (15%)

|

|

Bronchoalveolar carcinoma

|

33 (1%)

|

|

No histology

|

1181 (20%)

|

|

Total number of histological types

|

|

0

|

1181 (20%)

|

|

1

|

4557 (75%)

|

|

≥ 2

|

303 (5%)

|

|

Metastatic site at time of diagnosis

|

|

Bone

|

1890 (31%)

|

|

Brain

|

1156 (19%)

|

|

Lung

|

1565 (26%)

|

|

Lymph nodes

|

2157 (36%)

|

|

Other

|

378 (6%)

|

|

Referral to hospital-based palliative care services

|

3724 (62%)

|

|

Place of death

|

|

Acute hospital bed

|

2547 (42%)

|

|

Hospice or palliative care bed

|

2532 (42%)

|

|

Out of hospital

|

962 (16%)

|

3 Patterns of hospital use, and supportive and palliative care (n = 6041)*

| |

Interval 1: first metastasis admission

|

|

|

|

Variable

|

Died during admission

|

Alive after admission

|

Interval 2: between metastasis and death†

|

Interval 3: death in hospital‡ after surviving metastasis admission

|

|

|

Total at beginning of each interval§

|

728

|

5313

|

5313

|

4440

|

|

Median days during each interval (range)

|

43 (30–254)

|

6 (1–181)

|

123 (0–2304)

|

10 (1–271)

|

|

Any hospitalisation

|

728 (100%)

|

5313 (100%)

|

4360 (82%)

|

4440 (100%)

|

|

Median bed days per person (range)

|

43 (30–254)

|

6 (1–181)

|

20 (1–515)

|

7 (1–195)

|

|

Any ED visit

|

422 (58%)

|

1682 (32%)

|

2707 (51%)

|

1860 (42%)

|

|

Median ED visits per person (range)

|

1

|

1

|

2 (1–3)

|

1

|

|

Median hours spent in ED per person (range)

|

8 (0–54)

|

8 (0–49)

|

12 (0–145)

|

7 (0–180)

|

|

Intensive care unit admission

|

72 (10%)

|

656 (12%)

|

288 (5%)

|

215 (5%)

|

|

Lung procedures

|

228 (31%)

|

1770 (33%)

|

897 (17%)

|

257 (6%)

|

|

Chemotherapy as inpatient

|

11 (2%)

|

221 (4%)

|

417 (8%)

|

18 (< 1%)

|

|

Radiotherapy as inpatient

|

78 (11%)

|

226 (4%)

|

235 (4%)

|

127 (3%)

|

|

No. of supportive care modalities

|

|

|

|

|

|

0

|

31 (4%)

|

2616 (49%)

|

1039 (20%)

|

1760 (40%)

|

|

1

|

72 (10%)

|

975 (18%)

|

935 (18%)

|

911 (21%)

|

|

≥ 2

|

625 (86%)

|

1722 (32%)

|

2388 (45%)

|

1724 (39%)

|

|

First palliative care

|

569 (78%)

|

531 (10%)

|

1176 (22%)

|

1448 (32%)¶

|

|

|

* Data are number of patients (%) unless otherwise indicated; percentages within rows do not reflect mutually exclusive groups. † Including death for patients who died outside hospital. ‡ Acute hospital or palliative care unit. § Within interval, this is the denominator for percentages. ¶ If the denominator for the first palliative care in this interval is 5313 (ie, patients who survived the diagnostic metastasis admission), the proportion is 27%.

|

4 Indicators of aggressiveness of care at the end of life* (n = 5313)

|

Indicator

|

No. of patients

|

|

|

More than one acute hospital admission in last 30 days of life

|

973 (18%)

|

|

Length of stay more than 14 days in last 30 days of life

|

3219 (61%)

|

|

Intensive care unit admission in last 30 days of life

|

251 (5%)

|

|

More than one ED presentation in last 30 days of life

|

68 (1%)

|

|

ED presentation in death admission in last 30 days of life

|

2225 (42%)

|

|

Chemotherapy in last 14 days of life

|

53 (1%)

|

|

|

ED = emergency department. * Includes death admission for patients who died in hospital.

|

5 Factors associated with death in the acute hospital

|

Death in acute hospital bed

|

Odds ratio (95% CI)

|

P

|

|

|

First receipt of palliative care

|

|

|

|

No palliative care

|

1.00

|

|

|

Within 30 days, during metastasis admission

|

0.27 (0.22–0.33)

|

< 0.001

|

|

≥ 30 days after metastasis and before death admission

|

0.25 (0.21–0.30)

|

< 0.001

|

|

Death admission

|

0.22 (0.19–0.25)

|

< 0.001

|

|

Sex

|

|

|

|

Male

|

1.00

|

|

|

Female

|

0.97 (0.85–1.10)

|

ns

|

|

Age, years

|

|

|

|

< 40

|

1.00

|

|

|

40–59

|

0.66 (0.33–1.31)

|

ns

|

|

≥ 60

|

0.59 (0.30–1.16)

|

ns

|

|

Private hospital

|

1.25 (1.10–1.42)

|

< 0.001

|

|

English speaking

|

0.82 (0.72–0.94)

|

0.01

|

|

Married

|

1.06 (0.97–1.16)

|

ns

|

|

Rural

|

1.62 (1.42–1.84)

|

< 0.001

|

|

Metastases

|

|

|

|

Bone

|

0.96 (0.83–1.11)

|

ns

|

|

Brain

|

0.88 (0.74–1.05)

|

ns

|

|

Liver

|

0.97 (0.82–1.15)

|

ns

|

|

Lung

|

1.16 (0.99–1.35)

|

ns

|

|

Lymph nodes

|

1.21 (1.04–1.39)

|

0.011

|

|

Other

|

0.95 (0.72–1.24)

|

ns

|

|

Total number of supportive care modalities

|

|

|

|

0

|

1.00

|

|

|

1

|

0.88 (0.73–1.07)

|

ns

|

|

2

|

0.65 (0.56–0.75)

|

< 0.001

|

|

Year of metastasis

|

|

|

|

2003

|

1.00

|

|

|

2004

|

1.09 (0.83–1.42)

|

ns

|

|

2005

|

1.15 (0.88–1.51)

|

ns

|

|

2006

|

1.08 (0.83–1.42)

|

ns

|

|

2007

|

1.27 (0.97–1.67)

|

ns

|

|

2008

|

1.07 (0.82–1.41)

|

ns

|

|

2009

|

1.15 (0.86–1.53)

|

ns

|

|

2010

|

1.20 (0.75–1.91)

|

ns

|

|

Days lived

|

|

|

|

< 90

|

1.00

|

|

|

90–179

|

0.89 (0.75–1.05)

|

ns

|

|

180–269

|

0.88 (0.73–1.07)

|

ns

|

|

270–364

|

0.74 (0.58–0.93)

|

0.012

|

|

≥ 365

|

0.77 (0.63–0.93)

|

0.006

|

|

|

ns = not significant.

|

more_vert

more_vert