Many Australian paediatricians have been, and will be, providing care to refugee or asylum seeker children. They come from countries evenly spread among Africa, Asia and the Middle East, and demonstrate a different disease spectrum to Australian children.1 Australia hosts about one refugee per 1000 inhabitants.2 Children are proportionally overrepresented, with around 40% of Australia’s refugee intake being less than 20 years old, similar to the global refugee population.3 These children bring unique medical, cultural, social and linguistic characteristics, and paediatricians need to know how to manage them (Box 1).15

There are scant data on how well paediatricians understand the health and health-related rights of refugees and people seeking asylum. Concerns have been raised that the medical profession’s knowledge is suboptimal.9,16 General practitioners and medical directors have limited knowledge of support services available to them.17 Only one-third of the GPs studied had used a professional interpreter service while managing refugees, while 60% knew that the Translating and Interpreting Service (TIS) is available free of charge.18 However, there are no data for paediatricians.

Refugees and people seeking asylum suffer from physical and mental health problems attributed to experiences in their country of origin, transit countries and Australian detention centres.15,19–21 Refugees and people seeking asylum attempting to access health care services in Australia face geographical, cultural and linguistic barriers.22,23 To best serve children and adolescents, paediatricians need to know about relevant screening practices and Medicare arrangements.24

We sought to determine the knowledge and attitudes of Australian paediatricians in relation to the health of refugee and asylum seeker children both onshore and offshore.

Methods

Questionnaire

To establish the sample for our survey, we began with the Royal Australasian College of Physicians (Paediatrics and Child Health Division) register of paediatricians in Australia and New Zealand. We used the filters “general paediatrician” and “community paediatrician” to select those practitioners most likely to be managing refugee and asylum seeker children. We removed those who were retired or were working overseas (eg, New Zealand). In November 2013, we sent an email to paediatricians on this list with a link to a SurveyMonkey online questionnaire (Appendix 1). We followed up with one reminder email in December 2013 and a final email in January 2014.

Our survey had six sections:

- terminology (clinical vignettes about a child’s visa status and legal guardianship);

- health care delivery issues (Medicare eligibility, fee waiver programs and interpreters);

- visa and screening process (communicable disease screening and transmission risks);

- support for Australia’s asylum seeker and refugee policies;

- support for Australian Medical Association [AMA] and Royal Australasian College of Physicians [RACP] statements; and

- respondent demographics.

We conducted a pilot questionnaire with medical students, who took 5 to 8 minutes to complete the survey, after which the survey was shortened.

Ethics

Ethics approval was granted by the Sydney Children’s Hospitals Network and the University of Sydney (HREC LNR/13/SCHN/266). No incentives were provided to participants.

Data analysis

Data were expressed as the percentage of valid responses for each question. We used IBM SPSS version 21 to compare responses (α = 0.05) by demographic characteristics (all determined a priori) with χ2 analysis, or a two-tailed Fisher exact test whenever there were less than five valid responses.

Results

Target population

There were 599 paediatricians in the RACP register working in “general paediatrics” or “community paediatrics”. After excluding duplicates and those listed as retired or semiretired, overseas or without an email address, 419 paediatricians remained. A further 76 were excluded due to the email bouncing or because they were no longer in practice in Australia, leaving 343 eligible paediatricians (Appendix 2).

Characteristics of respondents

There were 139 respondents (response rate, 40.5%). Respondents’ characteristics were broadly representative of all Australian general paediatricians (Appendix 3). Most of the paediatricians completed all of the questions (90.6%–100% for non-demographic questions).

Questionnaire results

There was no difference in the proportion of respondents who saw refugee and asylum seeker children more than once per month (versus less frequently) in relation to paediatricians’ sex (P = 0.45), training in Australia versus overseas (P = 0.36) or having less than 10 years’ clinical experience versus more (P = 1.00).

Asylum seeker terminology and legal guardian

Ali is a 12-year-old boy from Afghanistan who travelled to Indonesia by plane with his 15-year-old brother, then by boat to Christmas Island. Ali’s brother asked the Department of Immigration and Citizenship (DIAC) for protection from the danger they faced in Afghanistan due to their Hazara ethnicity.

Li is a 10-year-old girl from China who arrived in Australia by plane with her father on a tourist visa. The day after they arrived, Li’s father asked DIAC for protection from the danger they faced in China due to their membership of Falun Gong.

Most respondents correctly classified Ali and Li as “asylum seekers” (Ali, 113/139, 81.3%; Li, 114/139, 82.0%). A small majority correctly identified the Minister for Immigration and Citizenship as Ali’s legal guardian, given that Ali was an unaccompanied minor (83/139, 59.7%).

Medicare eligibility

Fatima is a 17-year-old who has recently fled persecution in Iraq. She comes to see you about a productive cough that has developed over the past few days. She is otherwise well. She informs you that she is not an Australian citizen but she cannot remember what visa she currently holds.

Sixty-five of 134 respondents (48.5%) correctly identified that all refugees hold Medicare cards, but only some categories of asylum seekers are eligible for Medicare. Practitioners who saw refugee or asylum seeker patients “more than once per month” were more likely to select the correct answer than others (15/21, 71.4% v 48/107, 44.9%, P = 0.03). Practitioners with less than 10 years’ experience were just as likely to select the correct answer as those with more experience (8/22, 36.4% v 55/106, 51.9%, P = 0.19).

Fee waiver programs

An intern at a tertiary hospital emergency department calls you about one of your patients, Maya, who has just presented in the final stages of labour. Maya is 17 years old and fled persecution in Fiji. She does not have a Medicare card. The intern asks you whether Maya will be required to pay for all medical costs associated with the admission.

Only 12 of 133 respondents (9.0%) correctly identified that fee waiver programs are available for non-elective services in most Australian states for asylum seeker patients who request treatment at public hospitals but who do not possess a Medicare card.11–13 Practitioners who saw asylum seekers more than once per month had no greater knowledge of these services compared with other respondents (1/21, 4.8% v 10/106, 9.4%, P = 0.69). Over a quarter of respondents (36/133, 27.1%) thought that the hospital administration decided whether to bear an asylum seeker child’s hospital costs.

Interpreters and Medicare

Dhati is a 12-year-old refugee from Nepal who comes to see you with a urinary tract infection. She is accompanied by a friend as she has very limited English.

Similar proportions of respondents would arrange a face-to-face interpreter (59/132, 44.7%) as a telephone interpreter (63/132, 47.7%), with no differences by demographic characteristics (Box 2). Almost half of the respondents who would use a telephone interpreter were not aware of the TIS Doctors Priority Line (29/63, 46.0%).

The vast majority of respondents (118/133, 88.7%) reported no prior knowledge of the Medicare eligibility hotline, but 99 of this group (83.9%) planned to use it in the future. There was no difference between the proportion of respondents who gained their degree in Australia versus overseas who knew of the TIS Doctors Priority Line (54/104, 51.9% v 13/23, 56.5%, P = 0.69) or the Medicare hotline (12/104, 11.5% v 2/23, 8.7%, P = 1.00).

Pre-departure screening

Mr and Mrs Nazif and their four children (Mohammad, 16 years, Sheeva, 14 years, Wasim, 12 years and Fahran, 8 years) fled Afghanistan for Indonesia, where they were granted refugee status by United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR). They are all well and none has any significant past medical history.

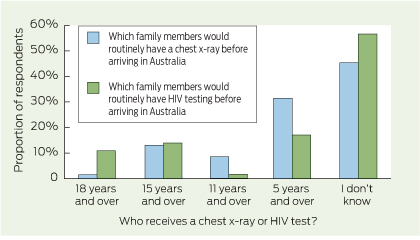

Very few respondents were aware which refugee and asylum seeker children would undergo chest x-rays for tuberculosis (TB) screening (11/130, 8.5%) and be tested for HIV (18/129, 14.0%) as part of their initial health screening (Box 3). The most common response was “I don’t know” (chest x-ray, 59/130, 45.4%; HIV, 73/129, 56.6%).

Most respondents (103/128, 80.5%) reported that they thought there was “no” or “low” risk of refugee children transmitting HIV or TB.

Offshore processing and mandatory detention

Only 17/127 (13.4%) of respondents correctly identified that most applicants wait in UNHCR camps for an average of more than 10 years before resettlement to Australia. Most (98/127, 77.2%) responded “1 to 10 years” to this question.

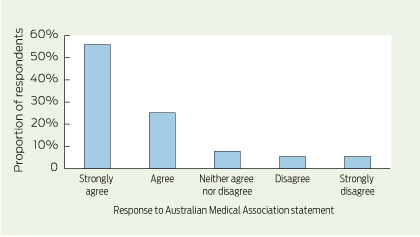

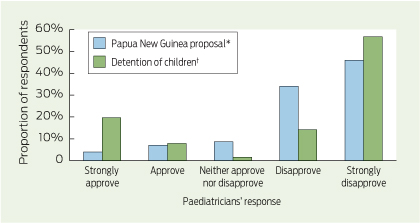

One hundred and one of 126 respondents (80.2%) disapproved or strongly disapproved of offshore processing in Papua New Guinea (PNG) and 103/127 (81.1%) agreed or strongly agreed with the AMA statement that detention of asylum seeker children was a form of child abuse (Box 4).25 Male respondents were more likely to approve of offshore processing than female respondents (13/66 v 0/58, P < 0.001. Ninety of 127 respondents (70.9%) disapproved or strongly disapproved of detention of asylum seeker children (Box 5). There were 25 respondents who “strongly approved” of detention of children. Of these, 23 “strongly agreed” or “agreed” with the proposition in the next question that “detention of asylum seeker children and their families is a form of child abuse”.

One in five respondents left comments, including:

- reluctance to use government services for asylum seeker children for fear of adverse consequences on the child’s visa application;

- concern about the “long-term damage” and the “high social, medical, psychological and hence economic costs” associated with current policies, in respect of which they were “appalled” and “ashamed”;

- “dismay” over the constantly changing nature of refugee and asylum seeker policies (“walking in a mine field when faced with this subject”); and

- “ ‘strongly disagree’ was often ‘not strong enough’ ”.

Responses by frequency of contact

Box 6 shows that paediatricians seeing refugee and asylum seeker children more than once per month were more likely than others to know: who had access to Medicare cards (P = 0.03); the Medicare hotline (P = 0.005); and that refugees accepted into Australia had stayed an average of more than 10 years in UNHCR refugee camps (P < 0.001). However, there were no differences in any of the other responses between these groups of paediatricians.

Discussion

This is the first study to investigate the knowledge and attitudes of Australian paediatricians about refugees and asylum seekers. This study also describes how paediatricians across Australia conduct consultations with refugee and asylum seeker children. Most paediatricians surveyed used the correct terminology of “asylum seeker” rather than “boat person” or “illegal immigrant”. However, we found serious gaps in knowledge in relation to Medicare eligibility, whether asylum seekers would be charged for essential health care, and the Medicare priority and TIS hotlines. There was also confusion about children’s screening tests during the visa application process. We found very strong support for the AMA contention that mandatory detention of children was a form of child abuse and overwhelming disagreement with the current policy of immediate removal of asylum seekers to PNG with no prospect of future immigration to Australia.

Two vignettes described the journey taken by Ali (by boat) and Li (by plane) to seek protection in Australia. Following recent policy and legislative changes, pursuant to sections 46A and 46B of the Migration Act 1958 (Cwlth), Ali would currently be classified as an “unauthorised maritime arrival” and would be barred from applying for a protection visa unless the Minister for Immigration and Citizenship (now Minister for Immigration and Border Protection) exercised his non-compellable discretion to lift this restriction.5 The terms “illegal immigrant” and “boat person” are not appropriate as applying for protection in Australia is a legal process provided for by the Migration Act 1958 (Cwlth) and consistent with Australia’s international obligations under the United Nations (UN) 1951 Convention Relating to the Status of Refugees and 1967 Protocol Relating to the Status of Refugees. The children in our vignettes could not properly be classified as “refugees” until their claims for protection were assessed on their merits.5

We found that most paediatricians understood that the Minister is the guardian of an unaccompanied minor.7 The Minister thus detains children while also being their legal guardian (with a duty to act in their best interests). To resolve this conflict of interest, the RACP in a position statement in 2013 called for an independent legal guardian for these children. As most paediatricians considered mandatory detention a form of child abuse, it cannot be in the children’s best interests.

We found gaps in paediatricians’ knowledge about Medicare eligibility. Medicare rights are held by all refugees and by asylum seekers who hold bridging visas to which such rights are attached.4,9 Although respondents who didn’t know the answer could ask colleagues and other contacts, the high percentage of “I don’t know” responses highlights the need for better training and education in this area. This is further complicated by some asylum seekers being supported by International Health and Medical Services (IHMS) and the Red Cross. However, these complexities were beyond the scope of this study.

Poor knowledge of hospital fee-waiver programs could limit access to hospital care and could be obstructed by this perceived cost burden, and health professionals might not be referring asylum seekers as they otherwise would.

Better knowledge of the pre-visa screening process may help to avoid duplications or omissions and thereby minimise financial and time burdens for patients and their paediatricians. This information is available — a copy of pre-departure screening results is given to Settlement Services International by the Department of Immigration and Border Protection on arrival. We are concerned that some health care workers may not know how to access this information and families are not being provided with it to bring to appointments.

Data derived by use of questionnaires are limited by potential responder bias; however, our sample was representative of Australia’s general paediatricians and responses did not differ greatly by demographic characteristics. Question wording and ordering may have resulted in our study underestimating disagreement with current policies. In questions 12 (approval of PNG proposal) and 15 (agreement with AMA statement that mandatory detention is child abuse), we outlined a policy or statement and then asked for approval or disapproval, whereas in question 14 (approval of detention of children), we outlined the RACP position calling for the end of detention for child asylum seekers, and then asked for approval or disapproval of detention of children (rather than of the RACP position). This may explain why almost all those who strongly agreed with detention of children also agreed with the proposition that mandatory detention was a form of child abuse.

Refugee and asylum seeker health care is complex with frequent government policy changes. Nonetheless, our findings show that there is considerable confusion about their legal and health access-related rights and the services currently available to assist in delivering care. As a group, paediatricians strongly oppose the detention of children and forced offshore processing of protection visa claims. Australian health care professionals need better training and education to be able to provide best practice health care to these most vulnerable children.

First, medical practitioners can ensure they have up-to-date knowledge of the health problems common among refugee and asylum seeker patients and develop an awareness of information sources and local services available to support the assessment and care of refugee and asylum seeker patients.

Second, medical practitioners can be important advocates for the rights of the specific children they see. This may include writing to the Minister to request that a child be removed from detention and that families be reunified. If such approaches are unsuccessful, the matter may be referred to the Commonwealth Ombudsman. Doctors may choose to contact their parliamentary representatives expressing support for the AMA, RACP and Australian Human Rights Commission positions on people who are seeking asylum and are in detention.

On 19 August 2014, the Minister for Immigration and Border Protection announced measures to enable children to be released from detention onto bridging visas, but only if they arrived before the arbitrary date of 19 July 2013. At the time of his announcement there were 876 children held in detention, including some in Nauru. All of these children should be released from detention immediately, irrespective of their date of arrival.

1 Practical information for managing asylum seekers and refugees

Terminology

- An asylum seeker is a person who is living outside their country of origin and has applied for recognition as a refugee.4

- A refugee is a person who is living outside their country of origin and has a well founded fear of persecution for reasons of race, religion, nationality, membership of a particular social group or political opinion.5

- An unaccompanied minor is a person aged < 18 years who has arrived in Australia without a natural parent or a relative ≥ 21 years old.6 The Minister for Immigration and Border Protection is likely to be the designated legal guardian of unaccompanied minors.1,7

United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) camps

- Refugees processed offshore have waited, on average, > 10 years in refugee camps run by the UNHCR before resettlement to Australia.1

Medicare eligibility and charging patients

- All refugees have Medicare cards and are entitled to health care cards under the same conditions as Australian citizens (some waiting periods are waived).8

- Some asylum seekers have Medicare rights attached to their temporary visas.4,9–10

- To check a patient’s Medicare eligibility, contact the Medicare enquiry number (132 150, press “1”) or access Health Professional Online Services (http://ww.medicareaustralia.gov.au/hpos).

- To check eligibility for the Asylum Seeker Assistance Scheme, contact the Australian Red Cross (02 9229 4111).

- A public hospital fee waiver program for asylum seekers without a Medicare card is available in most Australian states and territories (no formal policy found for Northern Territory and Western Australia). In New South Wales, a fee waiver is available for certain public health services including emergency care for acute conditions, some elective surgery, and ambulatory and outpatient care to maintain the health of patients with acute and chronic conditions, and to provide patients with maternity services and mental health services.11–13

Translating services

Screening

- Applicants for a permanent visa in Australia are required to undergo a chest x-ray for tuberculosis screening (those aged ≥ 11 years) and HIV screening (those aged ≥ 15 years or if there is a history of blood transfusions or clinical indications suggesting HIV infection, or that the child’s mother was or is HIV positive).14

- For more information on past screening and immunisations for patients in detention, please contact International Health and Medical Services Community Detention Assistance Desk on 1800 689 295 or email cdad@ihms.com.au.

2 Paediatricians’ responses to questionnaire items, by paediatrician demographic characteristics

| |

Sex

|

Where degree obtained

|

Clinical experience

|

|

Responses

|

Female (n/N)

|

Male (n/N)

|

P*

|

Australia (n/N)

|

Overseas (n/N)

|

P*

|

< 10 years (n/N)

|

≥ 10 years (n/N)

|

P*

|

|

|

Sees refugee children at least every month

|

11/59

|

9/66

|

0.45

|

19/105

|

2/23

|

0.36†

|

3/22

|

18/106

|

1.00†

|

|

Described Ali as an asylum seeker (Ali is a 12-year-old boy from Afghanistan arriving by boat with no visa)

|

53/59

|

50/66

|

0.04

|

88/105

|

17/23

|

0.26

|

19/22

|

86/106

|

0.76†

|

|

Described Li as an asylum seeker (Li is a 10-year-old girl seeking protection arriving by plane on a tourist visa)

|

51/59

|

54/66

|

0.48

|

90/105

|

16/23

|

0.06

|

15/22

|

91/106

|

0.046

|

|

Knew that the Minister for Immigration and Citizenship was Ali’s legal guardian as Ali was only accompanied by his 15-year-old brother

|

39/59

|

37/66

|

0.25

|

62/105

|

14/23

|

0.87

|

13/22

|

63/106

|

0.98

|

|

Knew there was a fee waiver for essential hospital-based care

|

7/59

|

4/65

|

0.35†

|

7/105

|

4/22

|

0.10†

|

2/22

|

9/105

|

1.00†

|

|

Knew some asylum seekers and all refugees had Medicare cards

|

32/59

|

31/66

|

0.42

|

48/105

|

15/23

|

0.09

|

8/22

|

55/106

|

0.19

|

|

Used phone or in-person interpreter when patient did not speak English

|

57/58

|

58/65

|

0.07†

|

96/103

|

21/23

|

0.67†

|

22/22

|

95/104

|

0.36†

|

|

Knew about Medicare hotline

|

8/59

|

6/65

|

0.45

|

12/104

|

2/23

|

1.00†

|

3/22

|

11/105

|

0.71†

|

|

Knew about Translating and Interpreting Service Doctors Priority Line

|

36/59

|

29/65

|

0.07

|

54/104

|

13/23

|

0.69

|

12/22

|

55/105

|

0.86

|

|

Knew who received chest x-rays before arrival

|

6/59

|

4/66

|

0.52†

|

7/105

|

3/23

|

0.38†

|

2/22

|

8/106

|

0.68†

|

|

Knew who received HIV screening before arrival

|

12/59

|

5/65

|

0.04

|

13/105

|

4/22

|

0.49†

|

3/22

|

14/105

|

1.00†

|

|

Considered that refugee and asylum seeker children posed a low or no risk of disease transmission

|

50/59

|

50/65

|

0.27

|

85/104

|

18/23

|

0.70

|

20/22

|

83/105

|

0.25†

|

|

Approved or strongly approved of immediately sending asylum seekers to Papua New Guinea

|

0/58

|

13/66

|

< 0.001†

|

11/103

|

3/23

|

0.72†

|

4/22

|

10/104

|

0.27†

|

|

Knew that refugees stayed an average of > 10 years in UNHCR refugee camps before settling in Australia

|

9/59

|

8/66

|

0.61

|

17/105

|

0/22

|

0.04†

|

4/21

|

13/106

|

0.48†

|

|

Approved or strongly approved of mandatory detention of children

|

11/59

|

24/66

|

0.03

|

27/104

|

8/23

|

0.39

|

6/22

|

29/105

|

0.97

|

|

Agreed or strongly agreed with AMA statement that detention of asylum seeker children was a form of child abuse

|

50/59

|

52/66

|

0.39

|

85/104

|

18/23

|

0.70

|

15/22

|

88/105

|

0.09

|

|

|

AMA = Australian Medical Association. n = no. of paediatricians giving each response. N = no. of paediatricians who answered question. UNHCR = United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees. * 5% significance was determined with χ2 analysis whenever there were more than 5 valid responses, and with a two-tailed Fisher exact test whenever there were less than 5 valid responses. † Less than 5 valid responses.

|

3 Paediatricians’ knowledge about tuberculosis and HIV screening of refugee and asylum seeker children*†

4 Paediatricians’ responses to Australian Medical Association’s statement that “detention of asylum seeker children and their families is a form of child abuse”25

5 Paediatricians’ approval or disapproval of offshore processing and detention of asylum seeker children

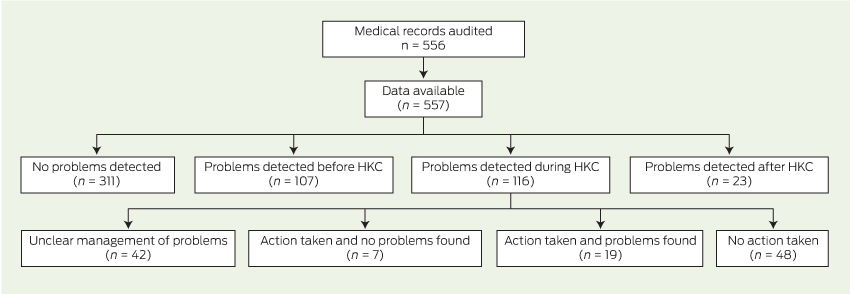

6 Paediatricians’ responses to questionnaire items by how often paediatricians saw refugee and asylum seeker children

| |

Frequency of seeing refugee and asylum seeker children

|

|

|

Responses

|

At least once per month (n/N)

|

Less often than once per month (n/N)

|

P*

|

|

|

Described Ali as an asylum seeker (Ali is a 12-year-old boy from Afghanistan arriving by boat with no visa)

|

17/21

|

88/107

|

1.00†

|

|

Described Li as an asylum seeker (Li is a 10-year-old girl seeking protection arriving by plane on a tourist visa)

|

19/21

|

87/107

|

0.53†

|

|

Knew that the Minister for Immigration and Citizenship was Ali’s legal guardian as Ali was only accompanied by his 15-year-old brother

|

12/21

|

64/107

|

0.81

|

|

Knew there was a fee waiver for essential hospital-based care

|

1/21

|

11/118

|

0.69†

|

|

Knew some asylum seekers and all refugees had Medicare cards

|

15/21

|

48/107

|

0.03

|

|

Used phone or in-person interpreter when patient did not speak English

|

20/21

|

97/105

|

1.00†

|

|

Knew about Medicare hotline

|

6/21

|

8/106

|

0.005

|

|

Knew about Translating and Interpreting Service Doctors Priority Line

|

12/21

|

55/106

|

0.66

|

|

Knew who received chest x-rays before arrival

|

4/21

|

6/107

|

0.06†

|

|

Knew who received HIV screening before arrival

|

5/21

|

12/106

|

0.13

|

|

Considered that refugee and asylum seeker children posed a low or no risk of disease transmission

|

17/21

|

86/106

|

1.00†

|

|

Approved or strongly approved of immediately sending asylum seekers to Papua New Guinea

|

1/21

|

13/105

|

0.46†

|

|

Knew that refugees stayed an average of > 10 years in UNHCR refugee camps before settling in Australia

|

8/21

|

9/106

|

< 0.001

|

|

Approved or strongly approved of mandatory detention of children

|

2/21

|

33/106

|

0.06†

|

|

Agreed or strongly agreed with AMA statement that detention of asylum seeker children was a form of child abuse

|

17/21

|

86/106

|

1.00†

|

|

|

AMA = Australian Medical Association. n = no. of paediatricians giving each response. N = no. of paediatricians who answered question. UNHCR = United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees. * 5% significance was determined with χ2 analysis whenever there were more than 5 valid responses, and with a two-tailed Fisher exact test whenever there were less than 5 valid responses. † Less than 5 valid responses.

|

more_vert

more_vert